The year 2014 ended with the hacking of Sony Pictures and the interrupted release of The Interview, a potty-mouthed, blood-spattered comedy about two hapless American journalists recruited by the CIA to assassinate the North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un. After Sony employees’ private data got leaked and executives’ catty e-mails became media fodder, vague online threats against theaters showing The Interview led to its being cancelled, then released on a limited basis.

One week into 2015, two French-born Islamist terrorists assaulted the Paris office of the magazine Charlie Hebdo, murdering 12 people and injuring 11 others. Over the next two days another terrorist killed a policewoman and may have wounded two others before invading a kosher supermarket, taking hostages, and murdering four more people. Before being gunned down by police, the attackers managed to kill 17 innocent people and wound 21 others, several critically.

On January 11, three million people marched through Paris in a show of unity against terrorism. At the same time, many pundits and culturati interpreted the slogan of that march, Je Suis Charlie, as embracing an uncompromising principle of free speech, in which all forms of expression, including obscenity, slander, hate speech, and blasphemy, are acceptable; and all curbs on expression, from voluntary restraint to coercive censorship, are unacceptable. A similarly uncompromising view of free speech inspired audiences in U.S. movie theaters to cheer at the scene in The Interview where Kim Jong-un gets incinerated by a Soviet-era flamethrower tank.

Yet no matter how solemnly or cheerfully invoked, this principle is not upheld in practice by any modern democratic nation, including the United States. For one thing, its logic is that of the slippery slope. Proponents begin with the axiom that every limit on speech or expression is a fatal step toward tyranny, then they conclude that the only way to avoid tyranny is to avoid all such limits. Apart from being circular, this argument fails to account for the fact that, although every society in history has curbed speech in some way, some societies have nevertheless remained freer than others.

The same logic leads proponents to blur the crucial distinction between coercive censorship and voluntary restraint. Obviously, this distinction is not black and white. Some forms of coercive censorship are “softer” than others. For example, an authoritarian regime will punish a few dissidents in order to create a larger “chilling effect”; a prison warden will isolate a troublemaker in order to intimidate his fellow inmates; a terrorist group will target one publication in order to silence others.

But coercion is not the only means of curbing speech. There is also voluntary restraint, and here we encounter another crucial distinction. When exercised by an individual, voluntary restraint is called tact, discretion, reticence, modesty, or prudence. When exercised by a society, it is called morality, custom, propriety, or taboo. Liberal elites in the West (and elsewhere) find it easier to defend the former than the latter, because they assume, with John Stuart Mill, that bourgeois society is mired in the subtle oppression of social conformity, and they believe that the only cure is for nonconforming individuals to express themselves in ways that are “edgy,” “irreverent,” or (best of all) “transgressive.”

There is nothing new about this dynamic. What is new is its playing out on a global stage where the threats to freedom are less subtle, and more dangerous, than social conformity. On this global stage, the most decisive battles over free speech will not be fought between bohemian artists and bourgeois philistines. Rather they will be fought between those who would defend the West’s fundamental political liberties and those who would destroy those liberties. To wage such battles, the West must do more than invoke uncompromising principle. It must reckon with its own ingrained assumption that cultural shock therapy is the best way to preserve freedom.

Setting Limits

To begin with the United States, the Americans who cheered the gory denouement of The Interview saw themselves upholding the nation’s sacred tradition of free speech. But nothing in the First Amendment obligates a private corporation to release a certain movie on a certain date. The Bill of Rights is focused on more important matters, such as the right of a citizen to speak, publish, demonstrate, and organize against any undue concentration of power—political, economic, or both—that threatens liberty and democratic governance.

During the 20th century, constitutional protection of free speech was expanded to include cultural expression. Throughout the 19th century, literature and the arts had been subject to legal censorship, although the preponderance of that censorship was on moral, not political, grounds. Indeed, when the courts began during the 1930s to rule against censorship of cultural expression, it was less because they rejected the claims of public morality than because they judged certain reputedly immoral works to be meaningfully related to the rights of citizens to express unpopular political views.

It took longer for the same standard to be applied to film. In 1915, the Supreme Court decision Mutual Film Corporation v. The Industrial Commission of Ohio defined the legal status of film as that of “a business, pure and simple.” That definition exposed film to regulation by the states, so in 1934 the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) adopted the Production Code, on the theory that voluntary restraint by the industry was the best way to stave off coercive government censorship. In 1948, the famous antitrust decision United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., took the first step toward redefining film as cultural expression. By 1968 this new status allowed the MPAA to scrap the Production Code and introduce the ratings system that, with some modifications, is still in place today.

But, as a glance at the Sony story reveals, the MPAA ratings system has been rendered toothless in today’s media environment. The Interview is rated “R” for “pervasive language [sic], crude and sexual humor, nudity, some drug use and bloody violence,” and to prevent anyone under the age of 17 from seeing it in a theater without being “accompanied by a parent or guardian.” The rating label also urges parents “to learn more about the film before taking their young children with them.”

Unfortunately, what most parents learn from the Sony publicity machine is that The Interview is an edgy, irreverent satire. This is true, to the extent that the film takes a few shots at America’s vapid celebrity culture and North Korea’s surreal propaganda. But parents taking their offspring to see The Interview will soon discover that it is one part satire to ten parts rectum jokes, boner jokes, vomit jokes, diarrhea jokes, death-by-poison jokes, death-by-automatic-weapons jokes, severed-fingers-spurting-blood jokes, Soviet-tank-and-helicopter-battle jokes, and finally the biggest joke of all: Kim’s face starting to melt before his body is engulfed in flame.

Parents who don’t want their offspring entertained in this way must do more than avoid the multiplex. They must monitor their children’s access to cable and the internet, because The Interview has been widely distributed on both. They must also be savvy about piracy: ask a 10-year-old to illegally download any Hollywood movie, and you may have to wait three minutes. And the same is true overseas. Ask a teenager in Pyongyang to locate a bootlegged DVD of The Interview, and you might have to wait three hours.

Just to clarify: the issue here is not the material itself but the unlimited scope of its distribution. After the Charlie Hebdo murders, highbrows of all stripes defended that weekly as part of a noble French tradition of caustic satire, much of it directed against religion. If you wanted to mount a similar defense of The Interview, you could go back to the Old Comedy of 5th-century Athens, in which the joining of obscenity with political satire was a regular feature of the spring festival of Greater Dionysos. The master of Old Comedy was, of course, Aristophanes—in a skillfully updated translation, his vivid sexual and scatological language can still raise the eyebrows of the average undergraduate.

The most Aristophanic scene in The Interview is the one where the smarmy talk-show host Dave (James Franco) finally gets to interview Kim Jong-un (Randall Park) on North Korean TV. After a couple of softball questions, Dave switches to harder ones, such as “Why do you starve your people?” Kim fires back with anti-American propaganda that Dave is too clueless to refute. But Dave recovers, and, playing on Kim’s emotional weakness, plays his favorite pop song until, weeping, he “pees and poops” in his pants. Witnessing this, the people of North Korea realize that their Supreme Leader is not a god, and rise to fight a democratic revolution.

Even if the rest of The Interview rose to this level, which it does not, the comparison with Aristophanes would reveal more difference than similarity. And the difference would be one of limits.

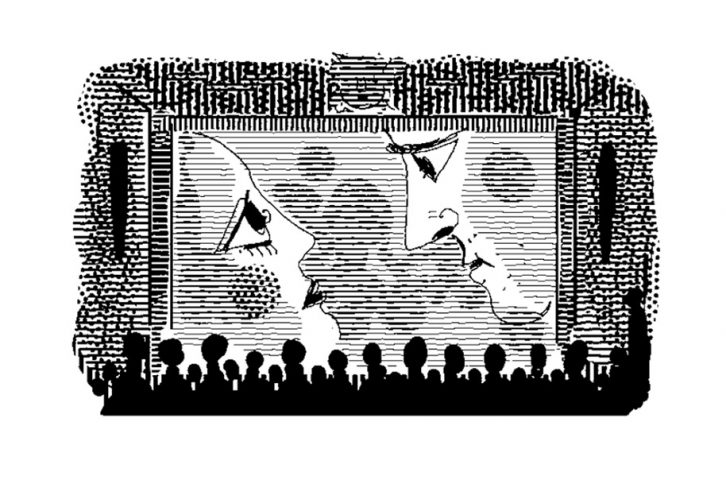

Drawing on cultic ritual and the custom of parrhesia, or uninhibited speech, Old Comedy flouted propriety and upended hierarchy. But in its original setting, it did so in a way that was carefully contained, like a controlled explosion in a laboratory. For example, there was no explicit violence in the Athenian theater, either in tragedy (where it occurred offstage) or in comedy (where it was not mentioned except in relation to war). Nor were comic playwrights allowed to depict respectable women, at least until Aristophanes wrote Lysistrata. And though all Athens attended these plays, the scripts did not circulate. When a performance was over, it was over—it did not go viral.

In the words of Jeffrey Henderson, general editor of the Loeb Classical Library and professor of classics at Boston University, the free speech of the comic playwrights “could be (and often was) punished if (and only if) it could be construed as threatening the democratic polis.” Comparing then and now, Henderson writes: “If the criticism and abuse we find in Old Comedy…seems outrageous by our standards, it is because we differ from fifth-century Athenians in our definition of outrageous, not because…comic poets were held to no standards.”

Kowtowing to China

To what standards do we hold our comic filmmakers? Most Americans would probably say, none. And to the extent that we consider freedom of expression an unqualified good, we would probably add that the global spread of films like The Interview is causing censorship and repression to retreat. Regrettably, this is not the case. By any reasonable measure—such as the latest report from Freedom House—the forces of censorship and repression are not retreating, they are advancing. And despite the cheering crowds in the multiplex, one place where they are advancing most effortlessly is Hollywood.

In 2013, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party released a Communiqué on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere, also known as Document 9, in which a number of “false ideological trends” are condemned, among them “constitutional democracy,” “universal values” of human rights, “civil society,” pro-market “neo-liberalism,” and “nihilistic” criticism of the Maoist past. Another “false” trend is “the principle of abstract and absolute freedom of press,” which threatens to “gouge an opening” in “China’s principle that the media and publishing system should be subject to Party discipline.”

Document 9 is rarely discussed in Hollywood, despite the dream factory’s long struggle to win the constitutional protections enjoyed by other U.S. media. As we’ve seen, American movies are not subject to censorship by local, state, or federal authorities; the Production Code is a thing of the past; and the MPAA ratings do little more than fuel the migration from theaters to the internet. But that doesn’t make Hollywood a no-censorship zone. On the contrary, the studios self-censor every day, for the narrowest of reasons: to corner overseas film markets, especially the huge, alluring one in China.

Ever wonder why so many Hollywood movies and TV shows take aim at North Korea, not China? To quote a colleague in the business, “Who cares what the North Koreans think? They don’t buy our movies!” With its impoverished population of 25 million, North Korea is not a tempting market. Nor does Pyongyang have a team of lobbyists defending its image in Hollywood (it may be getting one now). China, by contrast, has a $5 billion film market, only $1.78 billion of which goes to Hollywood; and Beijing’s lobbyists, if you can call them that, are legion.

Deadline Hollywood recently ran an article detailing the guidelines laid down by the Chinese authorities for foreign films seeking Chinese distribution. These include: “no vigilantism; no civil disobedience; police and military can have guns, but no guns or serious violence by Chinese civilians; no Chinese villains unless they are from Hong Kong or Taiwan and with Chinese heroes in place to balance the action; no explicit sex; no Chinese prostitutes.” The article concluded, “if your movie portrays China and its culture positively and takes that to an international stage, well, you’ll know exactly how Charlie felt when he unwrapped the Willy Wonka golden ticket.”

Consider Red Dawn, a 2012 remake of a 1984 film about American teenagers fighting a guerrilla war against a Soviet invasion. The production company, MGM, updated the movie by making the invading army Chinese. But during post-production, MGM got wind of hostile coverage in the Chinese press, and someone remembered how, back in 1997, an MGM film called Red Corner, which portrayed the Chinese criminal justice system in a negative light, had provoked a Chinese boycott of the studio’s films. A high-level meeting was held, and the writers and producers were ordered to create new footage and insert new dialogue making the invaders North Korean.

The question, therefore, is not whether Hollywood self-censors but why. At the moment, its only reason is the bottom line. To date there has been no serious industry-wide effort to develop standards of propriety suited to a global audience. Indeed, as the hacked Sony e-mails make clear, studio executives leave those decisions to the censorship boards that exist in every country, from Saudi Arabia to the United Kingdom. The hypocrisy of this policy was revealed when George Clooney railed against Sony for letting “an actual country decid[e] what content we’re going to have.” In an industry busy altering scripts, changing casting decisions, and editing final product to suit its new bosses in Beijing, such words ring pretty hollow.

Hate Speech

In his critique of John Stuart Mill’s “On Liberty,” the English writer James Fitzjames Stephen took issue with Mill’s tidy distinction between the individual and society: “By far the most important part of our conduct regards both ourselves and others,” he wrote. Stephen also challenged Mill’s animus against shared social norms—the notion, in Mill’s words, that “every one lives as under the eye of a hostile and dreaded censorship.” To this, Stephen’s reply was simple and straightforward: “The custom of looking upon certain courses of conduct with aversion is the essence of morality.”

To paraphrase Will Rogers, we are all self-censors, only on different subjects. No one seriously objects to voluntary restraints on speech when they reflect a society’s most deeply held values. For example, the inhibition against using the “N-word” to refer to African Americans is now widely accepted in America. The challenge is to develop the right rationale for a given restraint, and to expose that rationale to ongoing public scrutiny. Unfortunately, it takes a long time to instill a voluntary restraint, and the impulse is always present to speed up the process by passing a law or other coercive measure.

We see this pattern in the post-1960s American university, where informal efforts to purge academic discourse of racial bias, gender bias, and every other sort of bias have not succeeded fully enough to satisfy proponents. In the 1990s, these efforts suffered a setback when critics stuck them with the old Stalinist label, “political correctness.” The reaction by proponents has been as predictable as it has been counterproductive: the imposition of coercive speech codes on institutions whose chief raison d’être is free inquiry.

On a larger scale, the same pattern can be seen in continental Europe, where several countries have outlawed “hate speech.” For example, in France, where the civil-law tradition is more proscriptive than Britain and America’s common-law tradition, officials are accustomed to restricting speech and expression. Thus, France’s fundamental press law, passed in 1881, was amended in the 1990s to prohibit hate speech based on race, religion, gender, and sexual orientation. In 1990 the National Assembly passed the Gayssot Act, one of several Holocaust denial laws now on the books in Europe and Israel.

Supporters of these laws point out that France is home both to a large Jewish population and to a virulent strain of anti-Semitism, reinforced by the ressentiment of French citizens of North African and sub-Saharan African origin. The best-known exponent of this strain is Dieudonné M’bala M’bala, a mixed-race son of the banlieu who first achieved fame as a comedian working with a Jewish boyhood friend, but then went on to became France’s most notorious anti-Semite.

In 2007, Dieudonné (as he is known) reportedly told an audience in Algeria that Holocaust remembrances like the 1985 documentary Shoah were “memorial pornography.” In response, the public prosecutor in Paris found him guilty of hate speech and fined him $9,700. More recently, Interior Minister Manuel Valls (now prime minister) asked the Conseil d’État, France’s highest legal authority, to enforce a ban on Dieudonné’s performances, on the ground that they pose a risk to “public order” and “national cohesion.”

The French courts have also prosecuted Charlie Hebdo. In 2007, the Grand Mosque of Paris and the Union of French Islamic Organizations sued the weekly for reprinting the anti-Islamist cartoons that had originally run in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten. That case was dismissed when Charlie Hebdo’s editor, Philippe Val, argued that the cartoons were directed at fundamentalists and terrorists, not at the larger Muslim community. But other cases have succeeded, and like Dieudonné, the editors of Charlie Hebdo have—after paying their fines and lawyer’s fees—upped their game and become more obnoxious than ever. Indeed, there is something about a legal prohibition on speech that seems to provoke ever uglier and more defiant violations.

Granted, Charlie Hebdo has long been an equal-opportunity offender. In 2011, its response to a Catholic protest in Avignon against the exhibition of Piss Christ (Andres Serrano’s photograph of a plastic crucifix submerged in urine) was a cover showing three toilet paper rolls labeled “Torah,” “Bible,” and “Koran,” under the caption “Aux Chiottes Toutes Les Religions” (in the toilets, all the religions). Another cover, captioned “L’Amour Plus Fort Que La Haine” (the love stronger than hate), shows a rabbi and SS officer sharing a sloppy kiss at the gates of Auschwitz. On occasion, the magazine has run obscene images of priests—even one of Jesus sodomizing a depiction of God the Father.

Yet during the last decade or so, Charlie Hebdo has lavished particular venom on Islam. Consider, for example, a two-part edition of Charlie Hebdo published in 2013 under the title “La Vie de Mahomet” (the life of Muhammad). Drawn by Stéphane Charbonnier (also known as Charb, one of the cartoonists killed in the January attack), the series depicts Muhammad as a fat, ugly lecher with a bad case of priapism who in one scene has doggy-style sex with a fat, ugly version of the Coptic slave Maria al-Qibtiyya, while two of his fat, ugly wives look on.

It’s worth noting here that France has a law against hate speech based on religion, but no law against blasphemy. In other words, you cannot trash a fellow citizen whose sacred beliefs you abhor, but you can sure as hell trash his beliefs. I’m not a lawyer, but to me this distinction strongly resembles a hair waiting to be split. And that is precisely the problem. When the law tries to regulate speech, the line between sophistication and sophistry becomes blurred. And the result, in P.R.-speak, is bad optics.

Voluntary Restraint

In France today, the optics are that hate speech is forbidden against Jews, but permitted against Muslims. In a recent article in the Weekly Standard, Sam Schulman makes the intriguing suggestion that Holocaust denial laws may actually stimulate anti-Semitism. Although it is, of course, impossible to prove a counter-factual, after looking at data on anti-Semitic attitudes in countries with and without such laws, Schulman speculates that the subtle tides of social disapproval may be more effective at eroding prejudice than the rigid barriers of state censorship.

There are no hate speech laws in America, because our tradition relies more on voluntary restraints. Some of these have been harmful, it goes without saying. But others have been beneficial, and it would be foolish to cast them aside now. One such restraint is the inhibition against publishing or broadcasting material insulting to anyone’s religious beliefs. In my home state of Massachusetts, blasphemy has been illegal since 1697. But that is not what prevented the state’s newspapers from reprinting anti-religious cartoons from Charlie Hebdo. If a newspaper had reprinted the cartoons and been prosecuted under the old law, the case would have quickly run afoul of the First Amendment, not to mention the 1952 Supreme Court decision Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, which states: “It is not the business of government in our nation to suppress real or imagined attacks upon a particular religious doctrine, whether they appear in publications, speeches or motion pictures.”

Instead, what prevented the newspapers in Massachusetts and every other state from reprinting the Charlie Hebdo cartoons was custom. Upon hearing that their counterparts in Europe did reprint them, the instinctive response of most U.S. editors was, “We don’t do that here.” There’s nothing wrong with such a response, provided the reasons behind it remain open to challenge. But the editors who made that call were inundated with complaints like this one, sent to the New York Times: “I hope the public editor looks into the incredibly cowardly decision of the NYT not to publish the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. I can’t think of anything more important than major papers like the NYT standing up for the most basic principles of freedom.”

In reply, Times executive editor Dean Baquet explained that, although he understood the priority placed upon “newsworthiness” and “solidarity with the slain journalists,” his job required him to juggle these priorities with others, such as “staff safety” and “the sensibilities of Times readers, especially its Muslim readers.” In a similar vein, Washington Post executive editor Martin Baron stated that his paper did not run material “pointedly, deliberately, or needlessly offensive to members of religious groups.”

For their pains, both editors were accused of everything from spinelessness in the face of terrorism to (worse) obsolescence in the age of new media. Baquet in particular did not handle this well. First, his own public editor ran a column disagreeing with his decision, and he said nothing. Second, a professor at the University of Southern California accused him of “absolute cowardice,” and Baquet posted a reply calling the professor an “a–hole.” When that post went viral, another bite was taken out of American civility.

Americans don’t like censorship in any form, so we are easily persuaded to abandon our good judgment when accused of “self-censorship.” But the world’s most robust tradition of free speech and expression does not consist of a blanket refusal to set any limits. Rather it consists of a preference for voluntary restraint, both individual and communal, over coercive censorship, especially by the state. Much as Americans love liberty, we must not let that love blind us to the importance of occasionally holding our tongue.