Books Reviewed

For months, the businessmen, community activists, and other local boosters who make up the non-profit Lee Highway Alliance in Arlington County, Virginia, have been working to rename the county’s stretch of U.S. Highway 29, and thereby to repudiate the man whose name it bears. They want a name that “better reflects Arlington County’s values” than that of Robert E. Lee. Until the last couple of years, their task would have been delicate—in fact, preposterous. Not only was Lee the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, the greatest military strategist of the Civil War, the moral leader of the rebel Confederacy, and a paragon of certain gentlemanly virtues that people across the defeated South claimed (and claim) for their own—he is also history’s best-known Arlingtonian. Lee spent much of his adult life at Arlington House, built by Martha Washington’s grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, whose daughter Lee married. The county is named after Arlington House, not the other way around.

But Arlington, which sits directly across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., has been changing. Between the censuses of 1930 and 1950, it was transformed from hamlet to suburb, its population quintupling to 135,000. The New Deal, partly responsible for the change, did nothing to stint the local admiration for Lee, whom Franklin Delano Roosevelt called “one of our greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.” The military boom in Arlington, which began with the construction of the Pentagon and lasted through the Cold War, may even have firmed up Lee’s popularity.

Since the 1980s, though, Arlington has again nearly doubled in size, and its latest newcomers admire Lee less. Career military have been replaced by congressional staffers, lobbyists, and patent lawyers. Arlington suddenly finds itself the eighth-richest county in America (by per capita income), according to U.S. News & World Report. The new “army of northern Virginia” is proving large enough, progressive enough, and connected enough to transform institutions across the state. Neighboring Fairfax, the third-richest county in the country, recently renamed its Robert E. Lee High School for the late civil-rights marcher and congressman John Lewis. Several military bases in the state (including Fort Lee, near Petersburg, where Lee held Richmond against a Union siege for almost three hundred days in 1864 and 1865) will soon be renamed by an act of Congress. And if Virginia won’t honor Robert E. Lee, why should the country at large? Retired Army General Stanley McChrystal recently wrote an article in the Atlantic to announce that he had taken a portrait of Lee that his wife had saved up to buy him when they were first married, and thrown it in the trash. Perhaps more significant was what Americans did last year to commemorate the sesquicentennial of Lee’s death: nothing.

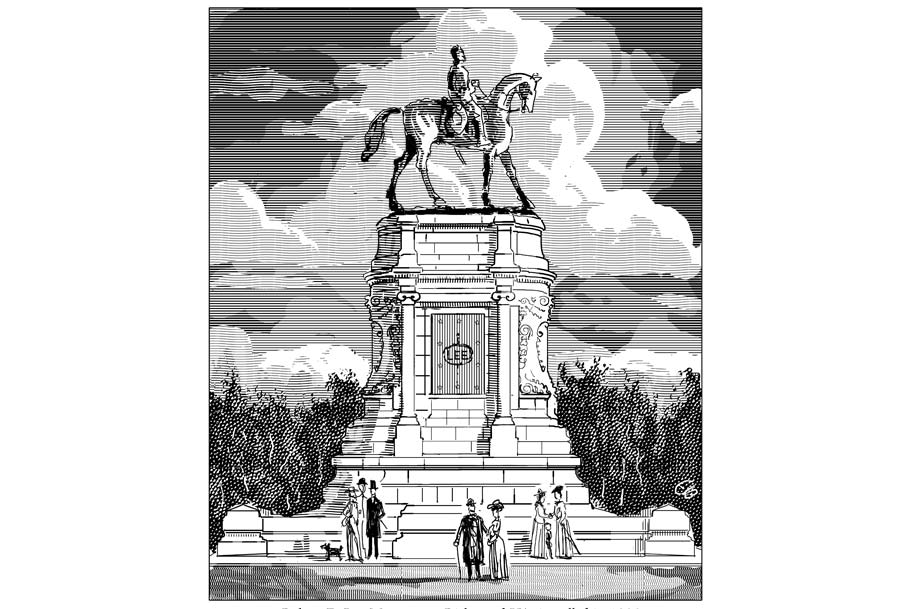

In the late spring of 2020, when protests broke out nationwide after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Richmond became the scene of mayhem impressive even by the standards of the time. Rioters pulled down two of the statues on Monument Avenue that commemorate leaders of the Confederacy. Days later Levar Stoney, Richmond’s mayor, ordered the removal of two more—a rare government-sponsored dismantling of a National Historic Landmark. He also ordered the removal of the oldest of the statues, the giant equestrian form of Lee by the French sculptor Antonin Mercié, hailed by artists and admired by tourists since its unveiling in 1890. Though a court stayed the order, protesters converged on the spot and covered the pedestal in graffiti, some roaming the grounds with AR-15 rifles. “You have certain Confederacy people, certain Klan people, certain Southern people who don’t want to see it down,” one armed protester told an interviewer. “They want to keep it up to remind us of the oppression, and we’re not having that.”

There is a strange thing about the historiography of our Civil War. So central is the event to the country’s self-understanding that every aspect of it is constantly being reassessed to answer up-to-date political questions. Civil War histories, even the masterpieces among them, can seem to have the longevity of newspaper articles. Who now reads Allan Nevins’s eight-volume standard history of the Civil War, Ordeal of the Union (1947-71)? Or Lord Charnwood’s Abraham Lincoln (1916)? Or for that matter, Douglas Southall Freeman’s four-volume R.E. Lee (1934-35)? Naturally, certain once-important historical reputations are destined to fade away.

That has not been Robert E. Lee’s fate. The conditions for rethinking his standing in American history have been present at least since the 1960s. But as the present generation has radicalized around race ideologies, opinion on Lee has become more frenzied and passionate than it has been since the height of the Civil War. He has suddenly become an object of hatred. The reputation for decency and honor that has clung to Lee since his death, even among the historians most critical toward the Confederacy, has not softened this new hatred but stoked it—as if the reputation itself were an insult launched across the centuries.

Man

As recently as 2014, biographer Michael Korda was able to describe Lee in Clouds of Glory as “universally admired even by those who have little or no sympathy toward the cause for which he fought.” Korda might have been thinking of Dwight Eisenhower, who considered Lee one of the four greatest Americans and hung his portrait in the Oval Office alongside those of the other three (Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Lincoln). “General Robert E. Lee was, in my estimation, one of the supremely gifted men produced by our Nation,” Eisenhower wrote, “selfless almost to a fault and unfailing in his faith in God. Taken altogether, he was noble as a leader and as a man, and unsullied as I read the pages of our history.”

Lee was certainly a multi-dimensional man. He graduated second in his West Point class, was gifted enough to become an assistant professor of mathematics at the age of 19, and spent much of his career designing fortifications and improving waterways for the Army Corps of Engineers. Attached during the Mexican-American War to General Winfield Scott, whom the Duke of Wellington would call “the greatest living soldier,” Lee excelled not just as a road-builder but as a warrior—a cavalryman with steely nerves and extraordinary physical endurance. His solo reconnaissance across a lava-strewn waste called the Pedregal allowed him to design a surprise attack when the U.S. advance on Mexico City appeared stalled. Scott called that mission “the greatest feat of physical and moral courage” of the entire war, and Lee “the very best soldier I ever saw in the field.”

It was on Scott’s urging that President Lincoln offered Lee command of the army that he was mustering to invade the South after the firing on Fort Sumter. Lee, then 54, refused, and resigned from the army to follow the course of the state of Virginia (which had voted against secession but now appeared likely to reconsider). In the summer of 1862, General George McClellan crossed the Potomac with 120,000 men, a force roughly twice that of Lee’s, and brought it to within earshot of Richmond. Until D-Day, it would stand as the largest amphibious invasion in the history of warfare, and the war appeared to be nearing its end. But in the so-called Seven Days battles at the end of June, Lee, having gathered more troops, drove McClellan’s army down the Virginia Peninsula and nearly destroyed it.

This is not the place to review Lee’s extraordinary performance as a commander over the three years that followed, or the reverence in which his men held him. The two were necessarily intimately connected. The South (9 million people, of whom 3.5 million were slaves) was vastly outnumbered by the North (21 million), and its technological disadvantages were even more extreme. In some respects, the war resembled those of certain colonial populations taking up arms against the British empire. The South never managed to manufacture guns, artillery, or gunpowder. It could not even manufacture blankets. Nor could it import those things, since the Union had a Navy and the Confederacy did not. The South was blockaded, and once Ulysses S. Grant’s troops had secured the Mississippi, the blockade was hermetic. At the end of the war, the South was using the same muskets it had in the beginning, with a range of 50 yards or so, while certain Northern units had new rifles with a range of 400 to 500 yards.

Lee was the moral force of half the nation. Lincoln came to understand this. In the late summer of 1864, while Grant was punishing Lee at the siege of Petersburg, army chief of staff Henry Halleck requested that some of Grant’s troops be sent to deal with draft resistance expected in the North. Grant categorically refused. He would not weaken himself in the standoff against Lee and run the risk Lee might escape and regroup. Lincoln telegraphed Grant: “Hold on with a bulldog grip and chew and choke as much as possible.” When in the spring of the following year, Grant broke the resistance at Petersburg, trapped the fleeing Lee at Appomattox, and forced his surrender, the war was effectively over, even though other troops remained in the field for days and weeks more.

Grant’s tracking of the evasive Lee’s wounded, starving men, the two generals’ exchange of letters, the solemn and utterly dignified ceremony (taunting forbidden, men enjoined to avoid “rencontres”), Grant’s magnanimous order that all Lee’s troops be permitted to return to their homes with their horses, Lee’s pledge of honor not to take up arms again—Appomattox is the most Homeric episode in modern warfare. And it accounts for the extraordinary reverence in which even Lee’s bitterest adversaries held him until what seems like the day before yesterday.

Hero

The first systematic Northern account of Lee as a hero not of the South but of the nation at large was that of Charles Francis Adams, Jr., who at the end of the 19th century wrote and lectured enthusiastically on the subject. Adams was above any suspicion of Confederate sympathies. Scion of the country’s most illustrious abolitionist family, son of the Free Soil Party’s 1848 vice presidential candidate (who was also Lincoln’s ambassador to the court of St. James’s), Adams fought against Lee in the war’s bloodiest battle (Antietam), served as colonel in a “coloured” cavalry regiment from Massachusetts, and was breveted brigadier general at war’s end.

For Adams, the beginning of wisdom is that it is extremely hard to bury the grievances that cause a civil war. “The essential and distinctive feature of the American Civil War, as contrasted with all previous struggles of a similar character,” he wrote, “was the acceptance of results by the defeated party at its close.” He credited Lee for preventing a hit-and-run guerrilla campaign of the sort that was raging in the aftermath of the Boer War just as Adams published his Lee at Appomattox in 1902.

Shortly before Lee left to meet Grant at Appomattox, Brigadier General Porter Alexander, the Confederate artilleryman, urged on Lee a strategy of scattering the army—to fight a guerrilla war, Adams assumed, correctly or not. Lee insisted on a formal, total surrender of every man and every weapon. “For us, as a Christian people,” Lee told Alexander, “there is now but one course to pursue. We must accept the situation; these men must go home and plant a crop, and we must proceed to build up our country on a new basis.” In the days that followed, Confederate President Jefferson Davis would call for a “new phase of the struggle” that would involve reconstituting the Army of Northern Virginia—and thus inciting soldiers to renege on the pledge of honor that Lee had made in their name. In Adams’s view, a durable peace between the sections followed Appomattox because Lee, not Davis, held the moral authority.

Authority to do what? The meaning of Adams’s viewpoint on Lee becomes clear only when one considers the constitutional nature of the rebellion in which Lee took part. Although Lee had opposed secession until the eve of Virginia’s leaving the Union, he believed his primary allegiance was to his state, and that that settled the matter. When questioned about his motivations for that allegiance before a Senate committee after the war, he responded, in essence, that his motivations had been neither here nor there. “That was my view: that the act of Virginia, in withdrawing herself from the United States, carried me along as a citizen of Virginia, and that her laws and her acts were binding on me.”

There is no reason to doubt Lee’s sincerity in this. The Declaration of Indepedence opens by recognizing the occasional necessity for “one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another.” A textbook used at West Point in his time taught that states had the right to secede from the Union. The very names of Civil War fighting units reflect that even in a national army troops were still mustered on the Jeffersonian assumption that defense is a prerogative of individual states. But Lee’s attitude sounded odd and disingenuous to Northerners even at the time. Adams, while he did not share it, was empathetic enough to lay out a reasonable route by which Lee might have arrived at this view: over the course of the decades, the advanced, “most far-seeing” part of the nation gravitated toward a unitary conception of the Union, suppressing ideas about state sovereignty that prevailed at the nation’s 18th-century origin. The backward part of the nation did not.

At least since the civil rights movement it has been common to make polemical use of the term “states’ rights,” as if that were always the pretext for anti-constitutional subversion. Adams was interested in the question of states’ allegiances. This question contained the seeds of “an inevitable, irrepressible conflict,” as he saw it, which could be resolved only when “men with arms in their hands [had] fought the thing to a final result.” Here is the heart of Adams’s point. Not all foundational questions get resolved at a nation’s founding, and if they are serious enough, they tend to be resolved by fighting.

It was perhaps Adams on whom Winston Churchill was drawing when he described the American Civil War as “the noblest and least avoidable of all the great mass-conflicts of which until then there was record.” Churchill is not using the adjective “noble” in the sense we do, as a synonym for “ethical.” He is implying that the resolution of the Civil War was a matter of heroism and greatness. That Robert E. Lee was one of the authors of the war’s resolution led the Unionist Adams to conclude that he deserved a monument not just in the defeated cities of the South but also in the heart of Washington, D.C. The conclusion was shocking at the end of the 19th century, but it seemed to be growing less so until around the turn of the present one.

Traitor

There was another, simpler, understanding of what Lee was doing. At the height of the Civil War it was common in the North to describe enemies of the Union as treasonous. Think of “The Battle Cry of Freedom”:

The Union forever!

Hurrah, boys, hurrah!

Down with the traitor,

Up with the star!

And because of the circumstances under which the war ended in April 1865, talk of treason did not end along with it.

At his cabinet meeting on the Friday after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln spoke of leniency, in line with the terms Grant had offered to Lee. But that was the last cabinet meeting of Lincoln’s life. The assassination at Ford’s Theatre that evening produced a raft of unfounded public gossip to the effect that the upper echelons of Confederate leadership had conspired with Lincoln’s killer, John Wilkes Booth. Lee soon became a target of the radical Republicans, as the prospect arose of a Carthaginian peace that they had despaired of imposing under Lincoln. A radical Republican congressman from Indiana, George Washington Julian, wrote in his diary: “The universal feeling among radical men here is that his death is a godsend.”

To Lincoln’s vice president and successor, Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat who had sided with the cause of Union, Lee the Virginia aristocrat was an arch-villain. Johnson despised slavery, not unreasonably, as an institution that damaged the interests of poor whites. His racial attitudes were primitive, his politics were those of class war, and he would have made a good 21st-century populist. He favored an amnesty for the common Confederate soldiers who made up his political base—but he vowed to use the powers of the office to punish the grandees whom he saw as slavery’s beneficiaries. Johnson engaged Judge John Underwood, a New York-born Virginia abolitionist, to seek an indictment of Lee for treason.

In The Lost Indictment of Robert E. Lee (2018), John Reeves, an editor of the financial newsletter the Motley Fool, gives a highly readable account of this little-remembered episode. Johnson’s plan fell apart for reasons both practical and principled. Ulysses S. Grant opposed the prosecution “vehemently,” in Reeves’s description, as breaching the agreement by which he had ended the war, and warned Johnson he would resign his commission if Lee were arrested. In the end a constitutional issue was asserted, Attorney General Salmon P. Chase stating that, after the passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868, with its bans on office-holding for participants in the rebellion, further punishment would constitute double jeopardy.

Lee would be pardoned under a general amnesty at Christmas 1868, by which time Grant was president-elect. And yet Lee’s full civil liberties had not been restored when he died in 1870. In October 1865 he had signed an oath of allegiance to the United States, upon Grant’s reassurance and urging, but it disappeared. The vindictive Johnson had apparently pocketed it, and it was discovered only in the 1970s. In 1975, Gerald Ford signed legislation posthumously restoring all Lee’s citizenship rights. The margin of the vote tells us something about where Lee’s reputation stood even in that heavily “countercultural” age: it passed the Senate unanimously and the House by a vote of 407 to ten.

Lee had a good 20th century. The greatest biography of him remains Freeman’s Pulitzer-winning life—heroic and punctilious, if a bit purple for modern tastes. It has had its measured defenders and its measured detractors, though almost all readers accepted its assessment of Lee’s importance.

In our own century, things have changed. The urgent, invective-filled attacks on Lee that are beginning to appear would have seemed overheated even if the Civil War were still going on. Last winter, the retired general and West Point professor Ty Seidule published a book called Robert E. Lee and Me. In his limited scholarly writing he has dealt with Black Power protests against West Point, gender and warfare, and treason. He says that, in thinking about Lee, treason and slavery are “the two issues that today sear at my soul.”

This is a bizarre book, an attack on Lee written in the form of Seidule’s own autobiography. A native of Virginia’s Washington suburbs, he laments the many ways he was propagandized into a racist “Myth of the Lost Cause,” starting with children’s books about Lee and moving on to Song of the South (“Uncle Remus”) and Gone with the Wind. Strangely, he never records a single racist action these objectionable artworks caused him to carry out, or a single racist thought they prompted him to harbor. What they have provoked him to do henceforth is to urge that the language in which we talk about history be more ruthlessly policed. He calls slaves “enslaved workers,” plantations “enslaved labor farms,” and the Union army “the U.S. Army.”

Seidule writes with the truculence of one used to working in an institutional context (whether the army or the modern university is unclear) where people can be punished for disagreeing with him. “Racism” and “lies” account for any historical interpretation that diverges from the author’s own. The idea that Reconstruction might have failed, for instance, is “a lie, a racist argument through and through.” Seidule is affiliated with the very low-profile (one might even say secretive) Chamberlain Project. Set up and run by progressive investor and Democratic fundraiser Jonathan Soros and feminist Vivien Labaton, it connects retiring military officers to progressive liberal arts colleges (in Seidule’s case, Hamilton College).

Racist

The reassessment of Lee’s position in American history has almost everything to do with a shift in the way we talk about race. This shift has come about the way most recent shifts in intellectual fashion have—not so much because of any new historical information but because of the arrival in journalism and academia, by a process so gradual as to be almost imperceptible, of the bureaucratic oversight and litigative intimidation enabled by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Lee’s attitudes toward race and slavery have long been known. He was a slave-owner with a very low opinion of the institution. In a letter to his wife, he called it “a moral and political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it however a greater evil to the white man than to the black race.” Although the last part of this statement has provoked progressive gasps, it is the standard attitude of a pious and prayerful Christian of the sort he became under the influence of his evangelizing wife. It is consistent with thinking slaveholding damnable.

Lee clearly had a custodial attitude toward blacks. Summoned in 1866 to testify before a congressional committee, certain members of which may have hoped to gather information for an indictment against him, he opined that blacks could not “at this time” exercise suffrage responsibly, and would be prey to demagogues. And yet the Lees’ life with their slaves was complex. They entrusted their china, their valuables, and all their keepsakes of George Washington to their slaves. As the winter of 1864-65 arrived in Petersburg, Lee urged enlisting slaves in his army in exchange for their emancipation.

This sounds naïve of Lee, and it probably was. He was not an ideological person. It is not even clear which political parties he supported. But about his hatred of slavery, both in the abstract and in practice, there can be little question. His mother had 30 slaves, which she left to her several children upon her death. Lee didn’t attend the meeting where they were divvied up. Those he received were more a burden than a gift. One can debate whether Lee was a decent man trapped in a hated system—rather like someone who despises capitalism but must work for a corporation—or whether he was some kind of thoughtless hypocrite. This debate, in fact, is where attitudes on Robert E. Lee are most in flux.

In her groundbreaking Lee biography Reading the Man (2007) the late Elizabeth Brown Pryor leaned toward the latter view. Hers is an unusual book. She uses Lee family letters, including a large cache that resurfaced only in 2002, to focus on the Lee family domestic life, taking what historian Thomas Carlyle called the valet’s perspective. Pryor is not uniformly hostile to Lee—she even calls him “immensely likeable”—but she is constantly seeking ways to problematize the non-problematic. Of Lee’s gentlemanly conduct when wooing his wife, she writes, “It may be here that we see the first signs of a lifelong use of irreproachable conduct as an agent of power.” And for reasons that have little to do with the book’s (considerable) virtues and (occasional) flaws, Reading the Man has become something of a bible for Lee-haters, from Seidule to the rather large Lee-watching team at the Atlantic (not just General McChrystal but also author Ta-Nehisi Coates and reporter Adam Serwer), who comb it for incriminating passages.

Pryor’s Lee is different. Whereas most biographers since Freeman paint him as an 18th-century holdover, a man of the founders’ generation adrift in the industrial age, Pryor sees him as a modern, even progressive figure. This comes partly from the way she views his scientific training and partly from the way she views his marriage. Most biographers present Mary Lee as selfish, spoiled, deaf to her husband’s greatness. Pryor adores her. “She was never disloyal or unsupportive,” Pryor writes, “but she had an identity beyond matrimony and chose to honor it.” And finally, she views Robert E. Lee as culpably implicated in the Southern slave system.

Lee’s father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, had almost 200 slaves at his various estates, including 63 at Arlington. Though George Washington had ordered his own slaves manumitted in his will, many of those belonging to his wife Martha Custis were “dower” slaves from the estate of her first husband, and could not be manumitted by law. Slavery at Arlington was a highly unusual arrangement, “comparatively benign” as Pryor puts it. The Custises taught their slaves to read and write (though it was illegal in Virginia), spent large sums on their health, and worshiped alongside their slaves at a small tabernacle in the woods. (Pryor is inclined to credit a story of Lee’s dropping to his knees to take communion alongside a black man who had had the temerity to walk into St. Paul’s church in Richmond after the war, since “Lee had worshiped next to slaves all his life.”)

Custis believed his slaves were better off than the average English peasant. In material and nutritional terms this may have been true. By the time he died in 1857, most of his slaves were growing their own food, not his. His complicated and somewhat ambiguous will stipulated that they be manumitted within five years and gave instruction on how certain of his estate’s debts should be settled. The slaves themselves, under the impression they had already been freed, began to run away. It fell to Lee to take a long leave from his cavalry post in Texas to restore order to the estate. He was a much-resented taskmaster, especially when he hired out slaves to distant plantations.

In 1866, the National Anti-Slavery Standard published an interview with a one-time runaway slave, Wesley Norris, who claimed Lee had had him whipped after capture in the late 1850s. Historians have been disinclined to believe this. Norris was a slave whom Lee had said he “could not recommend for honesty,” and the abolitionist press had low standards of evidence. Pryor stresses that Lee’s behavior as his father-in-law’s executor was in most respects exemplary. Carrying out Custis’s will cost him money. But on balance she believes the slave’s story. The names Norris cited in his account match real people, Pryor finds, and family accounts from the time show large payments to a constable Norris named as involved in the capture. That a slave would be whipped after escaping was not unusual—such punishment was prescribed by law. But that is precisely the problem, whether or not the story is true. Norris’s account is a vivid reminder that no one consents to slavery without violence, and to be a slave-owner, even briefly, even unwillingly, is to be an agent of that violence.

Pryor’s private narrative, with its focus on hypocrisies and compromises, has been gratefully latched onto by Lee’s detractors as the corrective to Douglas Southall Freeman’s public narrative, with its focus on battlefield glory. She welcomes this comparison. “He needed no publicists,” she writes of Lee. “They only diminished him, reducing a complex person to a stone icon. By denying Lee’s common follies and foibles, his devotees removed him from us, setting him apart, so that his true ability to inspire was obscured.” This is nonsense. Lee is known to history for his heroic deeds, which pose questions to posterity because they are unique. His “common follies and foibles” are just that—common. Severed from the deeds they are mere psychology, no more worthy of study than the follies and foibles of the other 33 million Americans who endured the Civil War. Like Lee’s own battle campaigns, perhaps, Pryor’s book is a magnificent execution in the service of a dubious cause.

Muddling the public and the private is what happens under an inquisition. All political action is delegitimized by it. No public figure can survive it. It calls to mind one of the darker days of the Trump Administration, in 2017, when violent extremists (“on both sides,” as the president put it) had flocked to Charlottesville, and the president was being pressured by reporters to say whether he favored taking down a statue of Robert E. Lee. “So this week it’s Robert E. Lee,” Trump said. “I noticed that Stonewall Jackson’s coming down. I wonder, is it George Washington next week? And is it Thomas Jefferson the week after?” This was too much for one reporter, who shouted, “George Washington and Robert E. Lee are not the same!”

The reporter was jumping to conclusions. When the U.S. capital was moved from New York to Philadelphia in 1792, President Washington resorted to subterfuge to keep Ona Judge, who was Martha Washington’s enslaved maid, and seven other slaves from taking advantage of Pennsylvania’s anti-slavery laws. When in the spring of 1796 Judge escaped on a ship to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Washington sent emissaries to reclaim her and considered using the existing Fugitive Slave Law to claim her back. Understood as slave owners, Washington and Lee are the same. The iconoclasts’ ambition to topple every Lee statue and rename every Lee high school and thoroughfare will not long remain confined to the Confederate cause. It will not be stopped short by any second thoughts over the face on the quarter and the dollar bill and the name of the capital city.

American

The controversy over Robert E. Lee is not just a matter of “refighting the Civil War.” On the contrary, it denies the relevance of the Civil War as we have up till now understood it.

Charles Francis Adams, Jr., described Appomattox as “the most creditable episode in all American history.” He was correct, and in the century and a half since no episode has arisen to surpass it. At its center is the encounter between the two warriors, the victorious Grant and the vanquished Lee, the lack of arrogance or enmity on either side, in fact the outright patriotic tenderness in both men, beginning with Grant’s first letter to Lee, which reads in its entirety:

The results of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the Confederate States army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

And then Lee arriving at the McLean farmhouse in his dress uniform the following afternoon, carrying George Washington’s sword, to surrender his army and renounce its cause.

That is not the way things appear in the official video of the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, the one that visitors watch before they tour the park. Race is its focus. It informs us that there were “United States Colored Troops” just west of the area at the time of the surrender, that half the population of Appomattox County were slaves, before concluding: “Emancipation set the country on a path to equality, and that path has proved to be long and steep. [Ku Klux Klan pictures shown.] But a first step was taken here—at Appomattox.” Race has played an important role in American history, of course, but at the present time it is not in much danger of being downplayed, and it has little to do with what is most remarkable about Appomattox.

Appomattox concerns Grant and Lee. The Park video concedes, “To Grant, Lee was a man of great dignity.” To Grant? Say what you will about Lee, to whom was he not a man of great dignity? A year later, the London Evening Standard would write: “A country which has given birth to such a man as Robert E. Lee may look the proudest nation in the most chivalric period of history…fearlessly in the face.”

Some people might fume at this effusion, but Lee cannot be offered a different role in the story of the Civil War without altering the meaning of what Grant did, what Appomattox meant, what the Civil War settled, and what the United States stands for. If Lee is a racist scoundrel, then Grant is either a gullible man or an accomplice. Appomattox, far from being the moment when Americans began to reunite with malice toward none, with charity for all, becomes the moment when whites—North and South—unite against blacks, an episode in the history of a tyranny, a tyranny we inhabit to this day, which stands in need of a root-and-branch reconstruction.

This is what many iconoclasts of our day sincerely believe. One of the great contemporary delusions is to assume that, when rioters tear down a statue of Thomas Jefferson or demand that an Abraham Lincoln school be renamed, they are demonstrating their historical ignorance, and have somehow “got the wrong guy.” Oh, no. They reject the idea that the Civil War was fought between a morally pure North and a morally irredeemable South. In this they have a point. The war was indeed fought between two sections that had each tolerated slavery to varying degrees, and finally faced an irreconcilable difference over whether any part of that institution could be tolerated. But there has been a shift in our understanding of what this means. Whereas earlier Americans understood slavery primarily as a problem of liberty, today’s Americans understand it primarily as a problem of race. It seemed for several generations that the end of slavery had removed the only obstacle to honoring both sides of the Civil War. But in the newest generation, the persistence of American racial prejudice can be a reason to honor neither.

Although there may have been ambivalence about the war’s origins, there was none in its resolution. “In the course of three and a half years,” wrote the British military historian Spenser Wilkinson a century ago, “the resistance of the Confederacy was crushed, its cause lost, and every interest and principle that had been invoked in its behalf abandoned for ever.” Abandoned forever is right. Whether they were erected in that spirit or not, Confederate statues, road names, and ceremonies today betoken the settlement of the constitutional and moral question from which the Civil War arose—not the reopening of it.

“Human nature will not change,” Lincoln said shortly after his re-election in 1864. “In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak and as strong, as silly and as wise, as bad and as good. Let us therefore study the incidents of this, as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to avenge.” That is the spirit in which Americans have tended to remember, and should remember, Robert E. Lee, one of the bravest and most principled among them, even if his bravery is of the sort they cannot always match and his principles of the sort they cannot always honor.