Books Reviewed

Critics of Norman Podhoretz’s The Prophets: Who They Were, What They Are, charge the book with turning the biblical prophets into American neoconservatives. Judith Shulevitz, writing in The New York Times, explains the message of Podhoretz’s prophets as “to vote Republican and back the war against Iraq.” Indeed, virtually all reviewers have felt compelled to address the “prophets as neoconservatives” question in one way or another.

More interesting, albeit as yet unnoticed, is the contentious status of the Hebrew prophets within the higher ranks of intellectual neoconservatism. “It is interesting that the Jewish prophets never much interested me,” Irving Kristol wrote in his Neoconservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea. Podhoretz, as if by rejoinder, argues in the introduction to The Prophets that “the worst thing of all that has been done to the prophets has not been to caricature or misrepresent but to ignore them.”

The Kristol-Podhoretz split over the relevance of the prophets parallels their two different intellectual styles. For Kristol neoconservatism has nothing especially to do with his Judaism or Jewish identity (rumblings from the fever swamps and The American Conservative notwithstanding). “[F]or 1,800 years, from the birth of Jesus to the Enlightenment, no one paid any attention to anything the Jews were saying, and the world went on perfectly OK,” Kristol once told The Jerusalem Post. “We have nothing more to say that is original that I’m aware of.” Indeed, Kristol once told an Israeli audience that the one thing needful for Jewish politics was “to translate the classics of Western political conservatism into Hebrew.”

This advice could never have come from Norman Podhoretz, the longtime editor of Commentary magazine, who speaks from a more explicitly Jewish perspective. In his last book, My Love Affair With America, Podhoretz linked his political commitment to his Jewish heritage and emphasized the important influence of the Jewish tradition on American politics generally. Podhoretz recalled learning from his predecessor at Commentary, Elliot E. Cohen, that the failure to preserve Jewish culture in America would not only be tragic for the Jews, but would “rob the country of one of the pillars on which it rested.” For Podhoretz, the Jewish tradition still offers a unique and vital message (one, he has suggested, that has found its warmest reception in the United States). The great texts of that tradition, as he sees it, retain their political relevance even 3,000 years after their composition. And it is to the prophetic writings that Podhoretz turns for guidance in our politics today.

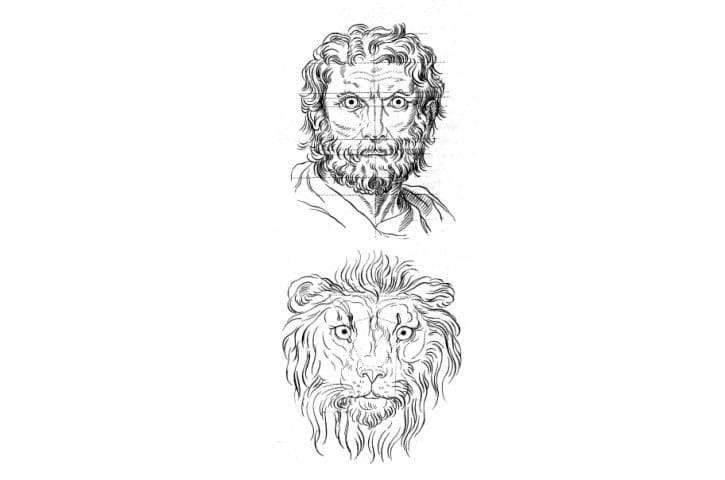

To be sure, Podhoretz is not entirely sanguine about the political example of the Hebrew prophets. The most influential passages from the prophetic books have been utopian visions of world peace. Among these, the best known is probably from the Book of Isaiah: “They shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more,” says the prophet, providing what has by now become a thoroughly worn-out anthem for modern anti-war movements. And Isaiah goes still further, foreseeing an end to violence throughout the animal kingdom: “The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.” Podhoretz’s verdict on such visions is that they “have proved more dangerous than uplifting,” for they have inspired the worst sort of political ambition. “[R]evolutionaries of the modern era from Robespierre to Lenin, from Mao to Pol Pot, who set out to realize the utopian visions of a world of perfect justice, harmony, and brotherhood felt justified,” he writes, “in constructing totalitarian regimes and murdering as many millions as they thought it would take to create such a world.”

Podhoretz demonstrates in detail, however, that those who find in the prophets a utopian program of social reform do not know the prophets for who they really were. The First Zechariah, for example, is frequently cited as launching a sharp condemnation of militarism when he says, “Not by might, nor by power, but by my spirit, saith the Lord of hosts.” But, as Podhoretz notes, what Zechariah is really teaching is that God alone—and not human agency—can bring about the messianic age. One who believes in an almighty God will accept, of course, that He has the power so to transform the natural order as to eliminate violence from the earth. But, Podhoretz emphasizes, the believer must also accept that only God can perform those miracles and that such utopian aims lie far beyond the bounds of human action.

The “dream of peace” may be the prophets’ most renowned legacy, but “it is never entertained by the prophets for the world as it bloodily exists in the present and as it will continue to exist until the End of Days.” In fact, the biblical prophets (the First Isaiah among them) often acted as advisors to Israelite kings in the conduct of war. The prophets, as Podhoretz recovers them, were not preoccupied with some otherworldly mystical reality abstracted from everyday experience; “far from dealing in abstractions floating above the concrete details of daily life,” he writes, “all of them were always plunging down and dirty into the world around them.”

The kinds of modern readings that Podhoretz opposes have given rise to a contrary view, that the classical prophets—such figures as Amos, Hosea, Micah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Isaiah—represented a dramatic change in the religion of Israel. As the now-commonplace narrative has it, the classical prophets denigrated the ritualistic laws of ancient Israel in favor of an abstract morality—”God requires devotion, not devotions,” as the biblical scholar Shalom Spiegel put it—and signaled God’s transition from His particularistic covenant with the Jews towards a universal concern for all mankind. “Christological” readers of the Bible, for their part, who have mined the prophetic texts for predictions about the arrival of Jesus, have sanctioned this view. In their telling, the prophets began leading the faithful out of Jewish legalism toward a higher gospel of faith and love. Similarly, those Podhoretz terms “liberalogical” readers of the Bible, whose interest is in the prophets as activists for progressive social reform, see the prophets as discarding rigid and chauvinistic rites in favor of a universalistic and more abstract emphasis on the moral life.

* * *

Podhoretz employs an impressive wealth of biblical scholarship and his own close reading of the prophets to challenge these views. Israel’s pagan neighbors, who believed that the gods depended on men’s ritual worship for their own well-being, considered cultic rites to be valuable in themselves. It is true that the classical prophets challenged this idea (as, indeed, did some preclassical prophets: “Has the Lord as great delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices, as in obeying the voice of the Lord?” asks Samuel. “Behold to obey is better than sacrifice, and to hearken than the fat of rams”). For them, God was not dependent on a human cult, but the cult remained an essential part of living a moral life in obedience to God. Ritual observance was an expression of the people’s “knowledge of God” and their commitment to His covenant, and failure to be observant in this way could bring condemnation from the prophets as swiftly as any other immorality could. (“Thou has not brought Me the small cattle of thy burnt offerings,” God chastises Israel through the prophet Isaiah, “neither hast thou honored Me with thy sacrifices.”) There is no doubt, of course, that the classical prophets place a renewed emphasis on interpersonal morality. “Is not this the fast that I have chosen?” asks the Second Isaiah, in a famous example, “to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free, and that ye break every yoke?” Yet Isaiah concludes not with a rejection of ritual, but a defense of sabbath observance. Indeed, the ritualistic requirements of the Mosaic law could lead the prophets to the same rhetorical heights as their utopian visions of the end of days:

If you refrain from trampling the sabbath,

from pursuing your own interests on my holy day;

if you call the sabbath a delight and the holy day of the Lord honorable;

if you honor it, not going your own ways,

serving your own interests, or pursuing your own affairs;

then you shall take delight in the Lord,

and I will make you ride upon the heights of the earth;

I will feed you with the heritage of your ancestor Jacob,

for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.

Through Isaiah’s poetry one perceives a profound pedagogical purpose behind the sabbath, the observance of which helps lead people away from the temptations of pride and self-indulgence. His position seems to be that the moral virtues must be learned through the observance of the law. Isaiah never condemns the ritual fast either; he only protests that the people “serve your own interest on your fast day, and oppress all your workers.” And so the prophet’s objection is not that a focus on ritual observance obscured moral conduct, but that the people were not actually performing the ritual. The prophets, as Podhoretz documents in book after book of the prophetic works, never made any distinction between ritual and morality; both were equally a part of the moral law. The prophets, in fact, could not teach morality at the expense of ritual, because ritual observance was part of their pedagogical project. Without the observance of the ritual law, moral behavior inexorably fell away. Far from standing for the opposition of ritual to morality, the biblical prophets taught the intimate relationship between the two. Indeed, Isaiah’s famous vision of world peace begins with an image of a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem, where sacrifices could be offered.

In the same way that the prophets arrive at the ethical through the ritual, they come to a universal vision through particularity. The Jews are held to God’s law precisely because they have been chosen from among all the nations: “You only have I known of all the families of the earth,” God says through Amos, “therefore I will punish you for all your iniquities.” That God should have bestowed His special favor on any single people some find scandalous—Podhoretz, borrowing a phrase from Christian theologians, describes it as the “scandal of particularity”—but that is precisely what, according to the Bible, God did. And the prophetic vision is one in which His chosen people become as light unto the nations, their faithful devotion to the law serving as an example for all.

* * *

In making the case for the “scandal of particularity,” the idea that the prophets’ universal moral vision was inextricably tied up with the observance of the Mosaic ritual law and God’s covenantal relationship with the particular nation of Israel, Podhoretz underlines the nature of the prophets as focused not on some abstract or heavenly ideal, but on the world before them. In making his point, Podhoretz cites an essay by George Orwell about the Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi. The “other-worldly, anti-humanist tendency of Gandhi’s teachings,” Orwell wrote, could not “be squared with the belief that our job is to make life worth living on this earth, which is the only earth we have.” For the biblical prophets, the physical world was not the “illusion to be escaped from” that it was for the mystical Gandhi, but was the only world we have. Here, Podhoretz deduces a profound lesson from the biblical prophets, “that the highest spiritual and moral states to which human beings are capable of attaining can best—or possibly even only—be reached through engagement with the affairs of the world around one, emphatically including what seem to be, or even are, transient or petty or trivial.” With this, Podhoretz presents what can be described as a distinctively Jewish theological worldview.

There is a famous Talmudic story, concerning the apparently trivial matter of whether a certain oven was susceptible to ritual impurity, that illustrates this view:

Rabbi Eliezer brought forward every imaginable argument to support his position, but the rest of the sages disagreed with him. Said he to them: “If the law agrees with me, let this carob tree prove it,” whereupon the carob tree was torn a hundred cubits out of its place (others affirm, four hundred cubits). “No proof can be brought from a carob tree,” they retorted. Again he said to them: “If the law agrees with me let the stream of water prove it.” And the stream of water flowed backwards. “No proof can be brought from a stream of water,” they replied…. Again he said to them, “If the law agrees with me, let it be proved by Heaven,” whereupon a Heavenly Voice cried out: “Why do you dispute with Rabbi Eliezer, seeing that in all matters the law agrees with him.” But Rabbi Joshua arose and exclaimed: “it is not in Heaven” [Deuteronomy 30:12]. What did he mean by this? Rabbi Yermiah said: “That the Torah had already been given at Mt. Sinai; therefore we pay no attention to a Heavenly Voice, because You have long since written in the Torah at Mount Sinai, ‘After the majority must one incline.'”

In other words, the biblical law has already been entrusted to the sages, so that God has no standing to intervene in their legal disputes. In fact, God’s voice should be ignored when scholars are debating the proper interpretation of His law. “When scholars are engaged in legal dispute, what right have you to interfere?” as one rabbi puts it in the story. And God laughs, saying, “My sons have defeated Me, My sons have defeated Me.”

In Podhoretz’s telling, it is this idea that the prophets exemplify. We on earth are the keepers of the moral law and shouldn’t be looking around for supernatural miracles or voices to determine what it says. Podhoretz even cites the same biblical passage as Rabbi Joshua, Deuteronomy 30:11-14, and writes that “it has a better claim…than anything anywhere else in the Hebrew Bible, including the classical prophets, to be regarded as the elusive ‘essence of Judaism’ for which commentators have been searching from time immemorial”:

For this commandment which I command thee this day, it is not hidden from thee, neither is it far off. It is not in Heaven, that thou shouldest say, Who shall go up for us to heaven, and bring it unto us, that we may hear it, and do it? Neither is it beyond the sea, that thou shouldest say, Who shall go over the sea for us, and bring it unto us, that we may hear it, and do it? But the word is very nigh unto thee, in thy mouth, and in thy heart, that thou mayest do it.

The prophets did not address themselves to some otherworldly mystical reality. For them, the moral law was a living presence here on earth, entrusted to human stewardship. To be sure, they often spoke God’s words, but they directed their rhetorical fire towards human conduct on earth. Podhoretz notes that the idea of an afterlife is alien to classical prophecy; divine rewards and punishments are meted out in this life. For the prophets, as for Orwell, this is the only earth we have. And that is why Podhoretz believes they have “so much to say” even to Orwell and other non-believers “about the moral and spiritual dimension of this life and about the laws that tell us how to live it.”

* * *

At one point in the book, podhoretz chastises certain “ex-believers” who nevertheless sought “to extract and preserve the moral core that to the ‘modern mind’ remained valid even if no God existed to command and enforce it.” As he argues throughout The Prophets, the prophetic vision was inseparable from the religion and laws of ancient Israel which they sought to defend. They prophesied precisely out of a divine calling and urged obedience to God above all other considerations. Yet Podhoretz also suggests that the Hebrew prophets can speak “in the language of today”—even, “or indeed especially,” to those for whom God does not exist. And so Podhoretz extracts his own moral core: “The most important thing is that, even if this is the only earth we have, it is still governed by moral and spiritual laws, and that these laws are as binding on human beings as the laws of physics are on the natural world.” Interestingly, no classical prophet ever drew a distinction between the moral and physical spheres. Science has uncovered many mysteries of the physical universe, Podhoretz notes, and we can do the same with the human moral condition. Of course, there are severe limitations to human knowledge and understanding. Just as science has been unable to discover the highest mysteries of creation, writes Podhoretz, the moral law will always be shrouded in mystery. This makes the prophetic voice all the more imperative.

The Prophets arrives at a judgment that is at once arresting and out of step with other modern critics, locating the essence of the prophetic vocation in their prosecution of a “war on idolatry.” The classical prophets, Podhoretz succeeds in proving, continued in the tradition of their predecessors (that is, preclassical prophets like Moses, Samuel, and Elijah) in deriding the idolatrous practices of Israel’s neighbors. And they took it as their mission, above all, to extirpate idolatry from within the nation of Israel itself. The prophets were monotheists, for whom there existed a single, omnipotent, and invisible God in Heaven who had created the earth and defined its laws, natural and moral. And they called Israel to allegiance to Him above all. As Harvard’s Paul D. Hanson has written, “Israel’s cardinal contribution to political theory resides in the claim that no political structure, whether tribal, monarchical, democratic, or whatever, can bind the conscience of its citizenry with ultimate claims.” The prophets, by speaking in the name of God to all earthly authorities, reminded Israel that, while this may be the only earth we have, it is still governed by laws that are greater than any human power. Idolators, in contrast, worshipped the product of their own hands. They created for themselves what would serve as their ultimate authority, and so recognized no fixed objective law apart from their own devices. The essence of idolatry, for Podhoretz, is antinomianism. The prophets fought so fervently and valiantly against idolatry precisely because they stood, above all, for the proposition that the world is governed by a moral law.

The prophets’ primary enemy is ours as well, Podhoretz argues. What they knew as idolatry we today know as relativism. Whereas the idolatrous, in worshipping their own creations, were ultimately worshipping themselves, the contemporary “culture of narcissism” prays to the same deity. The political idea that Podhoretz finds so odious, that humans are capable of constructing a perfect world, is itself a product of self-deification. Love of self, we learn from The Prophets, is our idol to smash.

To be sure, Podhoretz is a bit unfair to ancient Israel’s pagan neighbors. He does cite the warning of Bible scholar Jon D. Levenson that “using the Hebrew Bible as a source for learning about paganism is like trying to learn about Judaism from the New Testament, where the parent religion is comparably misrepresented by polemical zeal.” In the end, however, Podhoretz is more interested in the polemic against paganism than in paganism itself. His task is to recover the vision of the prophets as they presented it—and the prophets were polemicists. So “paganism” in The Prophets refers less to the historical phenomenon than to the antinomian ideology that the classical prophets—and the more recent neoconservatives—combated. Indeed, Podhoretz does not recognize a necessary conflict between paganism and the prophetic vision. “Socrates and Plato and Aristotle may have been pagans,” he writes, “but they were no antinomians, and I cannot help feeling that their entry onto the stage of history in the middle of the 5th century B.C.E., almost at the very moment that the classical prophets left it, was an uncanny coincidence.”

Yet if the biblical prophets can be identified with the philosophers of Greek antiquity, something essential about the prophets has probably been lost. Podhoretz acknowledges that the argument about law he develops through his examination of the classical prophets is so general as to be purely formal. It does not address the content of the law or the competing claims of the various religions, biblical and otherwise. But Podhoretz notes that “the idea that the moral realm is governed by law becomes something more than an empty abstraction when placed against the background of a culture that has for all practical purposes denied or repudiated that idea.” Thus Podhoretz reveals his own polemical purpose in writing on the prophets: to recover the idea of moral law in a culture awash in relativism.

In this respect—and, one hastens to add, only in this respect—the prophets may really have been something like the neoconservatives, issuing to the political world around them a blistering call to first principles. But in arriving at this conclusion, one suspects, we are missing something about biblical prophecy. The prophet Ezekiel, for a period of 390 days, ate only barley-cake baked on animal dung to indicate that the people of Israel “shall eat their bread unclean among the nations.” However dedicated the ideological warriors at Commentary may be, one can’t exactly imagine them doing such things. (Nor, for that matter, would Ezekiel be especially interested in writing op-eds for The Wall Street Journal. “[I]t is not through political analysis that [the prophets] see what they see,” as Podhoretz observes; they speak the fiery word of God.)

Like the ex-believers who subscribe to liberalogical readings of the Bible, Podhoretz also takes some political inspiration from the prophets that doesn’t fully encompass who they were. That is an eminently sensible exercise, of course, and Podhoretz’s concluding polemical essay, “The Prophets and Us,” is quite powerful and largely persuasive. But it doesn’t accord with earlier parts of the book, in which liberalogical readers and others are taken to task for exalting politically attractive sections of the prophets and ignoring others. Thus The Prophets really consists of two separate works, rendered by the subtitle as Who They Were and What They Are. The first is a work of biblical scholarship in which Podhoretz’s liberalogical opponents have misunderstood or misrepresented the classical prophets and the second is a polemic in which Podhoretz’s liberal opponents are politically wrong.

Podhoretz’s last section includes rhetorical assaults on such perennial antagonists as feminism, environmentalism, and the Palestinian nationalist movement. His political combativeness will probably alienate some otherwise receptive readers, especially among academics. But Podhoretz is steadfast as a rhetorical warrior and one gets the sense that, like Jeremiah, he cannot keep silent. As Jeremiah would tell you—and as Podhoretz’s own personal history demonstrates—the prophet often sits alone.