Books Reviewed

Confusion about the Catholic Church’s teaching on capital punishment has raged ever since Pope John Paul II in 1997 had the universal Catechism of the Catholic Church revised to state that the death penalty is permitted only when “bloodless means” are insufficient to protect the common good. Many Catholics—even some highly placed, theologically and philosophically well-educated Catholics—hold that the Church teaches that authorized state execution for a crime is intrinsically evil.

Fortunately, Edward Feser and Joseph M. Bessette’s powerful new book, By Man Shall His Blood be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment, clears the fog. Feser is associate professor of philosophy at Pasadena City College, and Bessette is a professor of government and ethics at Claremont McKenna College who worked in criminal justice for several years. They neatly divide the book between them, each concentrating on his area of expertise.

Because we are no longer accustomed to rigorous arguments or a relentless appeal to logic, the prose is jarring. Rather than tentative terms like “it seems to me” or “I would like to suggest,” the authors prefer testosterone-fueled diction; regularly using terms such as “absurd,” “preposterous,” “simplistic,” and “reckless” when evaluating their opponents’ arguments. As much as such language has value for its wallop, novelty (in a scholarly work) and, yes, accuracy, the arguments are so strong, I timidly suggest, that perhaps the authors should have allowed readers to “draw their own conclusions” more often. But let me say, the book simply flattens its opponents. (Testosterone-charged prose is contagious!)

* * *

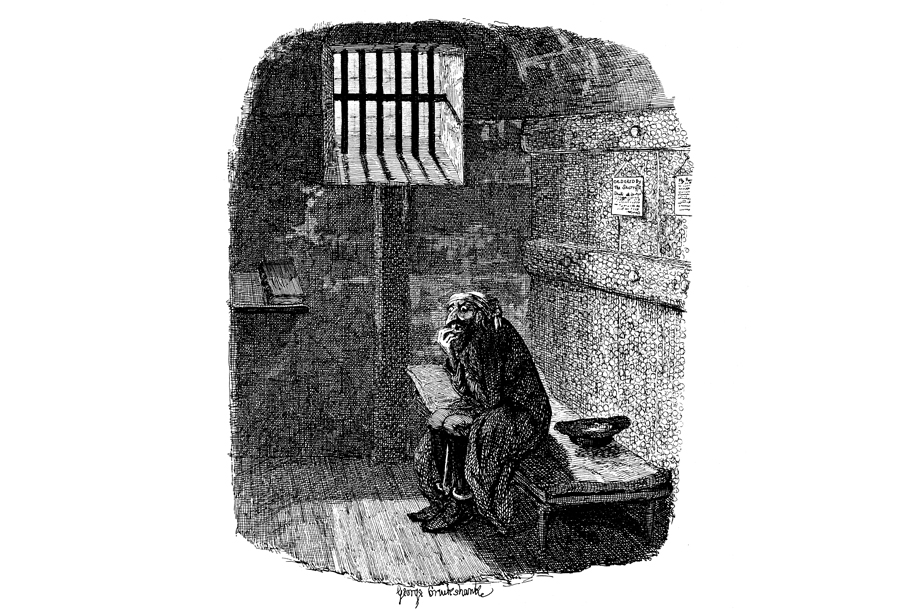

In the book’s first half Feser systematically refutes the arguments of those who think the Church now teaches that capital punishment is intrinsically unjust. He helps readers to see how weak our attachment to justice has become and how little we allow tight reasoning about justice to govern our thinking. The opening paragraphs of the book describe a hanging performed by an executioner who in the space of his 69 years killed 516 people—at the Vatican, at the behest of the Vatican. This will be the first of many unsettling moments for those who have blithely accepted the spirit of the age that assumes the incompatibility of capital punishment with Christianity and with a respect for life.

Feser provides a splendid, brief explanation of natural law and natural rights, and shows how the principles of Thomas Aquinas solidly establish the right of a state to use capital punishment to punish evildoers. Aquinas argued that the desire to punish is a virtue, and that retribution serves several good ends, most importantly that of maintaining order in a state. Feser painstakingly refutes the arguments of “new natural law” theorist E. Christian Brugger, an ardent opponent of capital punishment, effectively identifying some of the weaknesses of new natural law theory itself, such as rejecting a connection between fact and value. In a later chapter, contrary to Brugger’s claims that John Paul II implicitly taught that the death penalty is inherently immoral, Feser demonstrates that the pope in fact explicitly affirmed the right of the state to put criminals to death in some cases.

* * *

Feser thoroughly and carefully examines Scriptural approval of the death penalty, beginning with God’s instructions to Noah after the flood, in Genesis 9:1, 5-6 (from which the book’s title is taken), an emphatic approval of the death penalty. He notes that no one has successfully refuted the claim that the Bible unequivocally supports the right of states to execute some wrongdoers. Church Fathers, popes, theologians, and philosophers down through the centuries have accepted and amplified the teaching of Scripture in various ways, which Feser shows are eminently reasonable. He likewise shows that in both the 1992 and 1997 versions of the Catechism of the Catholic Church the Church reiterates what she has always taught: that capital punishment is fitting and legitimate for some crimes on the basis of retributive justice. Although the death penalty, like other forms of punishment, has several good purposes, including deterring others from criminal behavior, preventing the criminal from further crimes, and inducing a criminal to repent, the Church has consistently held that capital punishment is moral simply because some crimes are so heinous as to deserve the punishment of death.

It is true that the second and authoritative version of the Catechism seems to assert that recourse to capital punishment is moral only when there are no non-lethal means available to protect human life. Feser successfully argues that this “development” must be viewed as a prudential judgment by Pope John Paul rather than an authoritative teaching, and thus Catholics are free to contest it.

Feser observes that if the Church were to be wrong about something it has taught with such strong Scriptural basis and such unanimity throughout the ages, confidence in all Church teaching would be jeopardized. Catholics believe that the Holy Spirit prevents popes from teaching falsely in matters of faith and morals, and some of the current “controversies” in the Church would seem to bear this out. Brugger may be right that John Paul II personally thought capital punishment to be evil. But the fact that he did not officially teach this opinion—and instead confirmed the traditional doctrine—could be taken as evidence that the Holy Spirit kept him from doing so.

* * *

Joseph Bessette’s half of the book looks at the practice of capital punishment in the United States over the past several decades. Bessette provides grisly details of some horrific crimes in order to make the case that sometimes it is unjust not to employ the death penalty: the criminals deserve to die, the victims’ families deserve to see justice done, and our culture needs to restore order.

Bessette then turns his attention to the statements about capital punishment put out by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, which are seriously flawed—for one thing, they ignore Genesis 9:1, 5-6, an absolutely key passage. He reviews extensive studies on the death penalty’s deterrent power, on the number of persons unjustly condemned to death row, on the charge that racism causes the death penalty to be applied unfairly, as well as on the claim that it is applied unfairly to the poor. He uses this data to refute claims made by the bishops that capital punishment has no deterrent power, that innocent persons are regularly executed, that the application of the death penalty has been unfairly applied to minorities and the poor.

Overall, I find the arguments of the book altogether persuasive in establishing that the Church has taught and continues to teach that capital punishment is a fitting and just punishment for many crimes. Nonetheless, I believe there are more reasons than the authors allow for refraining from executing some criminals who have committed capital crimes. I believe we need to consider more fully the factors that lead a person to commit such terrible crimes as possibly mitigating the punishment deserved.

* * *

The case (featured in Feser and Bessette’s book) of Karla Faye Tucker executed in 1998 for brutally ax-murdering two people while high on drugs and with a history of violent behavior, has long fascinated me. There is no denying she committed terrible crimes but given the shape of her childhood, I find it difficult to assess her culpability. Her sisters introduced her to drugs when she was only 8, by 11 she was using heroin, and when she was 14 her mother introduced her to prostitution. I am not contesting that certain acts deserve the death penalty; I am asking whether some perpetrators are truly or completely responsible for their actions.

Shortly after her arrest, Tucker had a “born again” experience and committed herself to Christ. For nearly two decades on death row, she ministered to other prisoners and converted many to Christianity. It seems no one doubts the authenticity of her conversion. Many lobbied to have her sentence commuted but to no avail. She went to her death, truly contrite, manifestly acknowledging the wrongness of her behavior and the justice of her execution, confident in the Lord’s mercy. Such a person may well deserve the mercy of her fellow citizens, too. The common good may benefit more from her life than from her execution.

My demurral does not at all call into question the central argument of By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed that some crimes deserve death, and that this is now and has always been the teaching of the Catholic Church. Anyone who would claim otherwise must contend with Edward Feser and Joseph Bessette’s unparalleled—and I’m tempted to say, irrefutable—marshalling of evidence and logic in this important new book.