Macbeth famously saw a dagger that did not exist, but it is just as possible not to see something that does. Decades after knowing of George Soros it occurred to me that his last name is a palindrome. Were this a mark of the devil it would be entirely appropriate, inasmuch as Soros helped to dispose of the property of Jews sent to the death camps, and subsequently, in the flimsy guise of reform, has devoted his life to undermining fundamental institutions such as criminal justice. But in regard to what’s in a name, and to something that exists in plain sight and yet is not seen, why stop there?

His organizations are called the Open Society Foundations. Presumably this refers to the virtues of an open society, but it also brilliantly and perhaps mischievously lays out for anyone to see—even if hardly anyone does—the essence of his strategy. That is, to exploit the liberties of a free society so as to replace it with an entirely different regime, less open, less free, perhaps not free at all. In this he is no more original than Antonio Gramsci, Saul Alinsky, or the fundamentally-transforming-the-United-States-of-America Barack Obama, the Mount Everest of presumption, megalomania, and gall. But, better resourced and not needing to be either read or elected, Soros is more stealthy and more persistent.

The extraordinary freedoms of American society dictate that if the impulse to undermine and replace it arises from within, little can be done to counter it other than to mobilize methodical argument and ideological opposition, shielded by the guarantee of free speech. However, the modification, restriction, or outright abolition of free speech is a universal pillar of leftism that, as America dissolves, has exited the closet at the behest not merely of mad academics but of supposed moderates such as Hillary Clinton.

Paradoxically but imperatively, free speech must be upheld even though the aforementioned academics, Gramscian importations such as Herbert Marcuse, and homegrown figures like Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky will use it to challenge the political culture that ensures it. This is and always has been a test that must be met only with the sunlight of reason lest the fight to preserve freedom of expression results in ending it.

But when it comes to the tsunami of hostile initiatives and penetrations from abroad that now operate relatively undisturbed, it is possible to fight them vigorously and effectively, without violating constitutional norms, via the sovereign assertion of reciprocity.

Current American diplomacy is weak, pusillanimous, simpering, and, as Shakespeare might put it—and not merely in regard to Antony Blinken—“unmanned.” But deep in its severely compromised reflexes it must harbor the institutional memory of reciprocity. Perhaps the notable absence of this venerable and time-tested strategy is because willingness to make use of it requires recognition of certain postulates that too many Americans have been educated and propagandized—but I repeat myself—to reject. First, that the nation-state is a beneficial and just form of government to which the only alternatives are empire, confederations of small de facto nation-states, or anarchy. Second, that the nation-state can have legitimate interests. Third, that it is justified in promoting and defending these interests. Fourth, that it may properly do so independently of alliances. And fifth, that it can treat other nations as they would treat it, or, as it is said, reciprocally.

***

Of course, like almost everything, reciprocity should not be applied in all cases. For example, unwilling to subvert our own principles and protections even at what is often a steep price, we do not simply mirror other countries’ justice systems should Americans fall victim to them. In regard at least to opponents who qualify under the Geneva Conventions, we adhere to the laws of war even if our enemies do not. And yet if the price of this is steep enough (such as poison gas in World War I, or the Coventry bombings in World War II), we have sometimes reciprocally held sacred principles in abeyance, and no doubt will do so again.

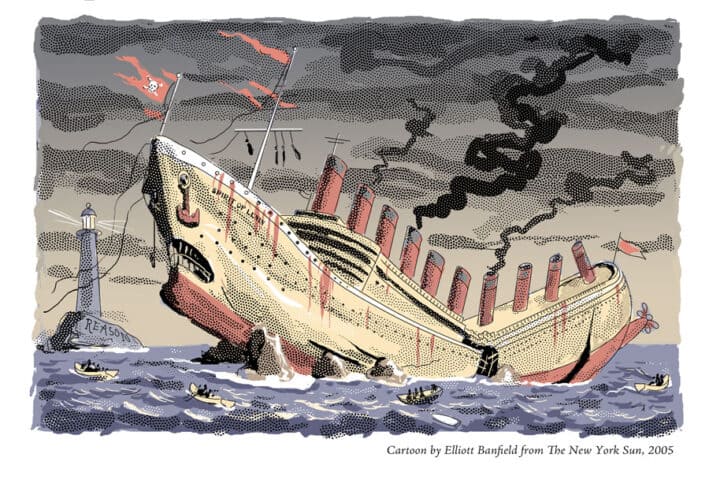

Though defending the open society from foreign predation is neither as grave nor as complicated as war, of late we have largely abstained and too much has been compromised without response. There are many examples of predatory foreign governments that have been allowed deep and continuing penetration—greater and lesser than balloons that traversed the country vacuuming up information and would have been unchallenged had not civilians reported them, or than Chinese hobbyists who fly drones over American shipyards that construct nuclear submarines. For example, although the numbers are now severely reduced, for far more than a decade, up to 100 Confucius Institutes financed and manned by the People’s Republic of China burrowed into American universities. Reciprocity would have required similar American institutions in China, similarly unconstrained—or a swift and concomitant disappearance of the Confucius Institutes in America.

American citizens can build as many mosques as they like, but for mosques financed and/or staffed by foreign powers reciprocity would require that American churches and synagogues have similar opportunities to operate, similarly protected and unconstrained, in those nations—and what are the chances of that?

One hears almost daily of cyber-hacking from China, Russia, and Iran. Why is it that one does not hear of American counterstrikes? That we are reciprocating seems unlikely, as it has had no deterrent effect. That we are saving our responses for more serious confrontation also seems unlikely, as our cumulative and continuing losses are equivalent to major strikes that go unaddressed.

Obviously, firm reciprocal actions can protect an open society from many if not all of its enemies. Just as obviously, it has not been forthcoming. Nor can it be expected from a nation that has been hypnotized so as to be embarrassed by its own existence, hostile to its own principles, and coy about asserting its own interests. The pity is that, unlike Macbeth’s dagger, the weapon of reciprocity does exist. The challenge for America is to be free enough of illusion and self-doubt so as to seize it.