Books Reviewed

Inferiority complexes can be debilitating. But in rare cases they can also be inspiring, or at least motivating. Consider Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Both wrote mysteries, and mysteries are down-market in the literary world—good for making money, but not for garnering prestige. Every writer wants to make money, of course, and the ones who know they’re hacks are satisfied by it. But the ones who think well of their abilities can be driven mad by a greed for prestige that makes mere avarice seem moderate.

After years of odd jobs, military service, failed careers, and plenty of liquor, Hammett and Chandler got rich through their writing. But success never made them happy, because neither achieved the success d’esteem in the literary world that he thought he deserved.

Chandler kept at it, writing progressively more ambitious books until he ran out of gas and spat out the underwhelming Playback the year before he died. Hammett never quite gave up either, but didn’t manage to finish a book in the 25 years that followed the publication of The Thin Man in 1934. This divergence may be traced to a difference of approach. Chandler never tried to abandon detective fiction, only to expand its literary possibilities, to do within its essential confines more than any mystery writer had ever attempted. Hammett, on the other hand, came to resent and despise the genre, and refused to write within it. So apart from Communist Party propaganda, he never wrote for publication again.

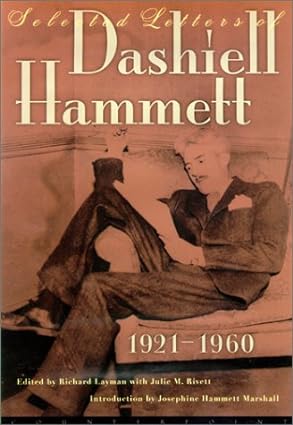

Alas, that didn’t stop Hammett’s biographer and two members of his family from bringing out a new book—a very large volume of letters. Most are mundane “Hi-how-are-yous” to family and friends. More than a third were written during Hammett’s army service in Alaska during World War II, and these are even more mundane. Another third are written to Lillian Hellman. Considering the legend that has grown up around “Lilly and Dash”—one of the most passionate love affairs of the 20th century, two great minds, two great talents, who never abandoned each other through the tribulations of depression, war, McCarthyite witch hunts, blah, blah, blah—these letters really ought to be far more interesting than they are. Forget literary or philosophic value —they don’t even contain good gossip.

By coincidence, a new volume of Raymond Chandler’s letters (along with some other scribbling) has also been published recently. Strictly speaking, this was unnecessary, as two editions of Chandler’s letters had already been issued: the uneven Raymond Chandler Speaking in 1962 (reissued in the mid-’90s), and, in 1981, the exhaustive, authoritative Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler. The editor justifies this new volume by claiming that he has discovered new material. And indeed he has. But one wishes he could have identified it in some way, for those familiar with the older editions.

In any case, the main effect of The Raymond Chandler Papers on anyone who reads it alongside Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett (and many will, for fans of one tend to be fans of the other) is to impress one with how much brighter, wittier, and more learned Chandler was than Hammett.

The Raymond Chandler Papers is the perfect book for anyone who ever wrote a letter, read it over, drew a deep breath, and imagined it being perused with awe some 40 years later by an industrious hagiographer. It is also the perfect book for anyone romantic about the first half of the 20th century, when heroic consumption of alcohol was de rigueur for the serious writer. Most people who’ve tried writing while drinking can recall scribbling something in an alcoholic haze, thinking it the most profound thing ever, only to realize in the unforgiving light of a hangover that it’s utter drivel. Chandler wrote most of his letters drunk. And they easily pass the sobriety test.

“I have written letters that would have made Eros hysterical and I have also written long serious letters on literary technique as well as I understand it,” Chandler once wrote to Hamish “Jamie” Hamilton, his publisher and frequent correspondent, who had suggested bringing out an edition of the letters. “It is true that in letters I sometimes seem to have been more penetrating than in any other kind of writing—at times—and that as I reread some of them, I really am astonished—astonished at the facility of expressions and at the range of thought I seemed to show even when I was a struggling beginner.”

This is not bluster; the letters really are that good. They amply demonstrate that Chandler deserved the prestige he craved but that eluded him in this country (though not in Britain). Of course, his novels should have accomplished that all on their own. But critics have a hard time getting around their prejudices. To them a mystery is a mystery, period.

Hammett fared somewhat better. In retrospect, it’s easy to see that whatever reputation he managed to cultivate in the highbrow world was due more to his radical politics and the company he kept than to genuine admiration for his works. His books were all published in the late ’20s and early ’30s. But the peak of his modest esteem came when, in 1951, he went to jail for refusing to disclose the whereabouts of 11 Communists (convicted of advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government) for whom Hammett’s Communist-front organization, the Civil Rights Congress, had posted bail. As a matter of fact, Hammett refused even to confirm his own name.

Hammett, as his letters make clear, never did get over his illusions about Stalin, or about Communism. Chandler, on the other hand, had none to shed. He once rebuked his leftist friend, James Sandoe: “You and I had better leave politics alone, since I am the reactionary type, who thinks that the only reason Uncle Dzhugashvili has no extermination camps is that he is still trying to find out how to get 50,000 miles out of a truck without greasing it.”

Of course, Uncle Joe did have camps. Chandler can be forgiven for not knowing because he didn’t pay much attention to politics, and he was never a Communist. But Hammett really had no excuse for believing, as he wrote to his daughter, that “the Communist Party does not now and never has advocated the overthrow of the United States Government by force or violence. Their (sic) stand on overthrowing governments is pretty much the same as Lincoln’s—that you only use force and violence when most of the people want a change and the few in power won’t give it to them peaceably.”

Chandler, though, had his own illusions, one of which is vetted in embarrassing detail in an interview he conducted with Lucky Luciano in Naples. Here it is, published for the first time. It makes for sad reading, for it only serves as proof that something toward the end had gone wrong in Chandler’s extraordinarily sharp mind. The piece ends, “If Luciano is an evil man, then I am an idiot.” This may be the most off-key sentence Chandler ever wrote, for Luciano surely was evil, and Chandler surely was not an idiot. Yet only someone in the grip of idiocy could have written an article called “My friend Luco.”

So what did these twin pillars of the “hard-boiled” style think of each other? It’s worth noting that they met once, in Los Angeles in the mid-1930s, at a party for current and former writers for Black Mask magazine—in terms of prestige and purse power, The New Yorker of the pulps. Aside from the fact that both men got uproariously drunk, no details of the encounter survive.

Hammett mentions Chandler only once, to praise his classic Atlantic Monthly essay, “The Simple Art of Murder” (which, not coincidentally, singles out Hammett as the best mystery writer of the age). For Chandler, Hammett was a literary hero who shook the mystery genre free of its aristocratic English pretensions and “took murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley. Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people who do it for a reason, not just to provide a corpse; and with means at hand, not with handwrought dueling pistols, curare, and tropical fish.” Chandler repeatedly singles out The Maltese Falcon for praise, which makes sense, because it was Hammett’s best book—the only one, perhaps, that deserves to live on. Chandler’s best-plotted book, Farewell My Lovely, owes much to The Maltese Falcon’s exquisite twists and turns.

But The Long Goodbye, Chandler’s best work, takes the character of Philip Marlowe much further than Hammett ever attempted with Sam Spade, or any of his characters. Here the gulf in their relative strengths as writers becomes apparent. With The Long Goodbye, Chandler accomplished what both men dreamed of: he wrote a serious novel worthy of taking its place on the shelves of serious literature. If in his lifetime he didn’t get the credit he deserved, at least his fans can take pleasure in knowing that some measure has accrued to him posthumously. And the more people read his witty, wide-ranging, and erudite letters, the more his reputation will rise.