Books Reviewed

George W. Bush set an ambitious national task in his Second Inaugural: henceforth, America would “support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.” He expressed no doubt about the outcome: “Eventually, the call of freedom comes to every mind and every soul. We do not accept the existence of permanent tyranny because we do not accept the possibility of permanent slavery.” This rhetoric—the “call” coming to every “mind” and “soul”—captured the new millennium’s popular fusion of faith and reason, where Christ meets Kojève in the possibility of universal satisfaction in a liberal world. It’s a harmonious picture of humans peacefully at home with themselves. Today, it seems an almost absurd characterization of our world—a beautiful vision of an imaginary place.

Waller R. Newell, professor of political science and philosophy at Carleton University in Ottawa, has devoted considerable attention in recent years to the problem of tyranny. His new book, Tyrants: A History of Power, Injustice, and Terror, provides an accessible overview and survey of tyranny, ancient and modern. It is full of fascinating and often frightening historical characters vividly depicted, and contains a carefully considered account of the would-be tyrant’s motivations. For those like Bush who hope policy can end tyranny once and for all, the news is bad: the “temptation to tyrannize” is a permanent element of human nature.

* * *

Newell identifies three types of tyrant—two with roots in antiquity, one distinctly modern. First are the “garden-variety” tyrants who treat their states as their private property. They rule solely for their own gain, luxuriating in opulence while their subjects fend for themselves, seeking military victories over weaker neighbors for their own greater glory. This type of tyrant has been known from the mists of prehistory through the present day.

Second are the “reformer” tyrants. Cyrus the Great, founder of the first Persian Empire in the 6th century B.C., and Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern Turkey 2,500 years later, exemplify the reformer. Likewise a figure both ancient and modern, the reformer tyrant’s vision of the good is broader than his own hedonic pleasure. These are the autocratic practitioners of “nation-building at home,” in Barack Obama’s memorable phrase. Some created empires; others overthrew empires and established new ways of living. Some built great cities or undertook vast public works programs or patronized the arts. Some augmented their personal rule by creating new forms of public administration. The often impressive achievements of reformer tyrants make them more morally ambiguous than their garden-variety counterparts—almost a kind of good tyrant.

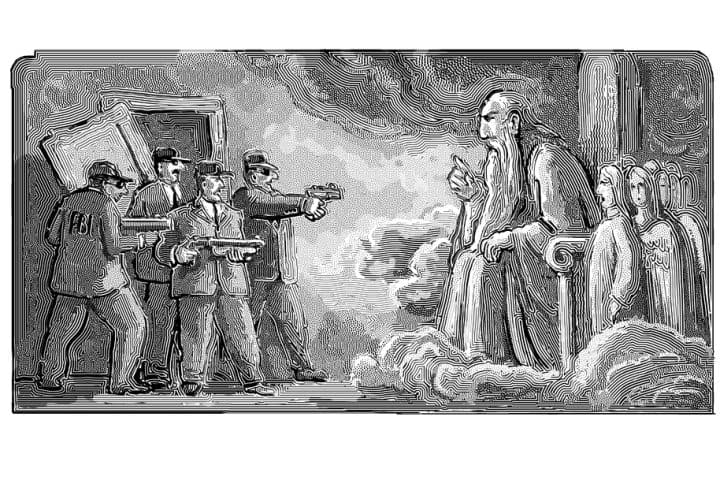

Newell claims his third category—“millenarian” tyrants—is new to the modern age. Distinguished by the scale of their brutality and ambition, Hitler, Lenin, Mao, Pol Pot and the like believed in politics’ transformative power in a way that never occurred to the most ambitious ancient ruler. The millenarian tyrant will discard any and all who don’t conform to his vision, excusing the slaughter of millions in pursuit of desired ends.

Newell traces this millenarian sensibility to the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who emerges as the biggest villain in a book with no shortage of claimants to the title. Rousseau’s view of man as naturally good but corrupted by society, argues Newell, made possible the Terror of the French Revolution. For millenarians, man’s rehabilitation is the urgent task of politics. Contrary to the American Founders’ more moderate principles—but much in keeping with the Marxist revolutionaries who marred the 20th century—the French revolutionaries sought a comprehensive transformation of French politics and society, and were prepared to do away with all actual and potential enemies of the new order. Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety believed they spoke for the “general will” of the people—and no individual could stand in their way.

* * *

Newell’s diagnosis of this tyrannical type allows him to connect it to the present-day phenomenon of Islamist terror. He finds the fire of millenarian tyranny burning hot in the breasts of many young Islamists today. Though they don’t rule (apart from a swath of Syria and Iraq), they aspire to it, and they promise to impose a new and uncompromising order when they do. Those who won’t accept their rule will surely face death. Slaughter on a scale that would dwarf the Holocaust lacks only the means, not the will.

The phenomenon of tyranny offers us a glimpse of politics at a greater extreme than we good (classical) liberals typically encounter in the developed world of the G-20 or the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Most of us know tyrannical politics only from the outside. This presents a challenge to scholars: in framing our assessment of tyranny and particular tyrants, do we assess them solely through the prism of our modern-day liberalism, or do we try to set that aside and view them in the context in which they arose?

Newell is well aware of this problem, though Tyrants contains no solution. The problem is most acute in his discussion of reformer tyrants. Classical liberals—and after the Cold War, that category includes almost all conservatives—can’t comfortably approve of despots, even if they do good works. Yet in the premodern world, judging an autocrat a great ruler without qualification on account of his wisdom, justice, statesmanship, and stewardship presented no contradiction. “Tyrant,” as Newell notes, originally referred simply to someone who rose to absolute power without some prior claim of right to it, such as dynastic succession. Pejorative connotations came later. Now we always use the term pejoratively. Newell clearly admires some of his reforming tyrants, but his liberalism stands—in many respects admirably—in the way of his ability to say so.

His treatment of Machiavelli is illustrative. He writes: “The ancients had taught that we should live within the order of nature and rein in our impulses. Machiavelli now offers the heady prospect that man can master nature, control his own destiny, ‘conquer Fortuna’ through bold and cool-headed action.” He proceeds with an admiring discussion of Henry VIII’s Machiavellianism—“for good or ill, one of the first examples of how a reforming tyrant could begin to achieve modernization from above.” Newell contrasts Machiavelli’s “call for the ‘outstanding prince’ to assert his will over nature” with the “godlike mandate” of Rousseau’s “Legislator” to “chang[e] human nature” and “transform each individual…into part of a greater whole.” But Rousseau walked through a door Machiavelli had already opened. Newell knows this; some pages before he writes that “no one before Machiavelli had suggested a ruler could actually and quite literally be God, recreating the world of man.” Because it’s either good to grant man a godlike mandate to overcome nature or it isn’t, readers of Tyrants will have a hard time avoiding the conclusion that either Newell’s case against Rousseau is overstated or his case against Machiavelli is understated.

* * *

This in turn suggests that Tyrants is missing something. For a fuller account of the path to millenarian tyranny and whether Machiavelli is to be loved and/or feared, one should turn to Newell’s earlier book, Tyranny: A New Interpretation (2013). There, he sets out to prove what Tyrants asserts, namely, that there is a decisive difference between ancient and modern tyranny, based on the different worldviews underlying them. The ancient view saw tyranny as deriving from eros, undisciplined desire that was susceptible, perhaps, to taming through education. The modern view sees in tyranny the godlike impulse to master and transform nature.

It’s a bold and provocative thesis. It also turns, to a remarkable degree, not on Machiavelli but on one of the greatest literary takedowns of all time, nearly 2,000 years earlier: Socrates’ demolition of Achilles as a heroic model in Plato’s Republic (a critique Newell accepts). In the guise of a discussion of the censorship necessary in the just city, Socrates paints Achilles as a petulant, spoiled brat unable to control his selfish impulses, starting with anger. Achilles is eros unchained—for Newell, a tyrannically-inclined soul.

Peter J. Ahrensdorf offers a very different view, one closer to my own, in his delightful book Homer on the Gods and Human Virtue (2014). Here we find a more reflective and truly great Achilles. In Ahrensdorf’s telling, Achilles hungers for glory because he deserves glory on account of his effort to embody virtue. If Achilles is not erotically disordered, as Dr. Socrates diagnosed, but legitimately “great in his greatness,” as Homer describes, erotic disorder may not be the whole story of the desire to assert one’s superiority over others—or even over nature and the gods. That would give modern tyranny a foothold in the ancient world. It could also lead us to underestimate the danger tyrants pose: what if they aren’t sick?

Newell ends Tyrants on an optimistic note reminiscent of the 43rd president: “democracy is bound to defeat tyranny because it’s simply a better idea.” I agree that democracy—or put more precisely, our liberalism—is a better idea. But if this is true now, it was also true in 1934. There is no reason to despair for the liberal future, but triumphalism must await a final triumph that will never come.