Although most Americans enjoy without even thinking about it a level of material ease and comfort unprecedented in history, our intellectual representatives—progressive writers, artists, pundits, and professors of the social sciences and what were once the humanities—habitually dismiss or scorn the technological and commercial achievements that have made this agreeable life possible. To do otherwise would be to damn themselves not only as philistines but as tools of the black-hearted business cabal bent on extracting every dollar’s worth of atmospherically devastating fossil fuels from the scarred earth. The civilization—the world—built on coal and oil and natural gas (now from the dreaded fracking) has fallen into disgrace, along with the inventions that made modern life possible, such as electrical power and the combustion engine.

One answer to “The Question Concerning Technology,” as Martin Heidegger called it in his 1954 essay—the only answer remotely reasonable—is more or better technology. And the same minds that deplore the environmentally sordid past and present may often be heard counting on the advantages of the uninvented. These bright new ideas will be the salvation of mankind, provided the greedy throwbacks do not prevent history from following its natural arc toward eco-justice.

It used to be that the bright new idea, that Eureka moment, was represented by an incandescent light bulb going on over the inventor’s head; but now incandescents burn too profligately to meet the latest standards for inventive benefaction, so that the light emitting diode and the compact fluorescent light—though not nearly as handsome as their outmoded ancestor—will evidently have to serve as the emblems of prodigious thinking. Whether the thinking will indeed be as prodigious as that which produced the Edison light, as the soft bright marvel used reverently to be known, remains to be seen. But successful or not, it will have to do. The old standby is as good as gone.

Giving Dinosaurs Their Due

That so many American intellectuals regret the technology they use every day is a fairly recent phenomenon, but the attitude has roots that reach back to the Industrial Revolution, or at least to its political aftermath. In a 1929 New Republic review-essay, “Edison and Steinmetz: Medicine Men,” the novelist John Dos Passos declared that serious American writers had better take notice of the sorts of practical minds that have really made the country what it is. “It’s about time that American writers showed up in the industrial field where something is really going on, instead of tackling the tattered strawmen of art and culture.” The men who got important things done, the ones “who counted in our national development during the last half-century,” need first-rate writers to tell their stories, for they were too busy to write their own stories, and had little inclination to do so in any case. “They carried practicality to a point verging on lunacy.” And lest one suppose that lunacy of this order must be a bad thing, Dos Passos enumerates the masterworks of one such seething brain:

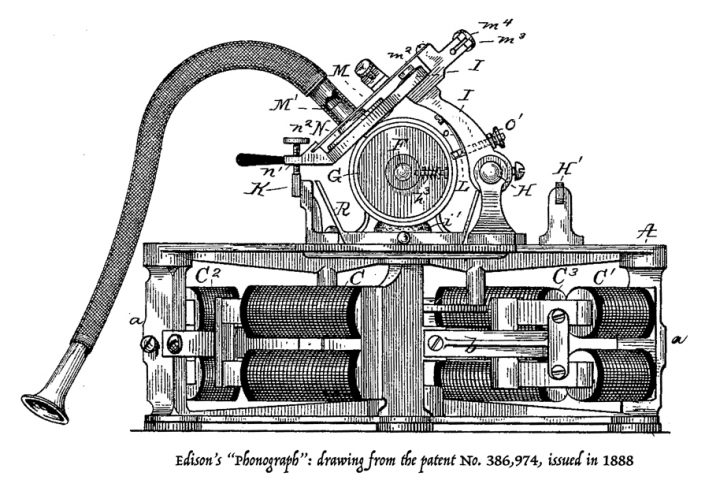

When you think that Edison was partially or exclusively connected with putting on the market the stock ticker, the phonograph, the moving picture camera, the loudspeaker and microphone that made radio possible, electric locomotives, vacuum electric lamps, storage batteries, multiple transmission over the telegraph, cement burners, it becomes obvious that there is no aspect of our life not influenced by his work and by the work of men like him.

It was not T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound who invented modernity, but the industrial wizards, and they had earned the grateful awe of ordinary Americans and of the extraordinary writer Dos Passos. “Edison, Ford, Firestone have cashed in gigantically on the machine. They have achieved a power and a success undreamed of by Tamerlane and Caesar.”

Dos Passos doesn’t mention this but he is writing less than two months after the stock market crash that inaugurated the Great Depression, and that brought American business enterprise to a new low in the estimation of forward-thinking men and women, such as most writers and readers of the New Republic. At the time not merely to defend technological and industrial giants such as Edison and Henry Ford, but to exalt them, was a feat of intellectual courage for a man of the Left; and though Dos Passos would vote for the Communist presidential candidate in 1932, he gradually grew disillusioned with the Marxist project, declared it a failure in a 1948 Life article, and in the 1950s became an impassioned conservative, while his reputation as a leading American novelist suffered a consequent and entirely predictable erosion. As for Edison, like the founders who did not live up to the egalitarian standards of the current virtuecrats, he is too far gone morally in contemporary eyes to be really estimable. He belongs to a bygone world of dinosaur aggressors insufficiently conscious or considerate of the fragility of our planet, which is imperiled by much too much of a good thing that really wasn’t all that good to begin with. To lionize Edison now, as the earth simmers on its way to boil, would place one irredeemably on the wrong side of history.

The Wizard

Thomas Alva Edison (1847–1931) in his day was a figure from American folklore buttressed with proud native fact: the self-made man and the uncommon common man. His teacher in the one-room schoolhouse in Port Huron, Michigan, considered him, at least according to legend, ineducable—though the fact might be that his father, a jack of all trades, could no longer afford the tuition fee. His mother, a former schoolteacher, taught him at home from the age of nine, reading to him from Edward Gibbon and David Hume, William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens, until he could read for himself. His father would observe, “Thomas Alva never had any boyhood days in the ordinary sense of the term; his early amusements were steam engines and mechanical forces.” At 12 he went to work hawking newspapers and sandwiches on the train for Detroit, leaving home at dawn and returning toward midnight; he set up a makeshift laboratory in a baggage car, until a phosphorus spill started a small fire and the conductor put the mobile chemistry set off the train. During the layovers in the big city he became one of the earliest members of the Detroit Free Library, which wasn’t free at all but cost a substantial two dollars to join. “I didn’t read a few books. I read the library,” he said. He loved Les Misérables but gave up on Isaac Newton’s Principia, which was a “wilderness of mathematics” he could not find his way through. He would say years later of his mathematical deficiencies that he could always hire a mathematician but no mathematician could hire him. Without anyone to guide him, young Edison read tomes of chemical analysis and practical mechanics. Matthew Josephson writes in Edison: A Biography (1959) that his adolescent self-education “disposed him to avoid the example of a Newton and follow that of a James Watt or of a factory mechanic like [Richard] Arkwright,” the inventor and entrepreneur who was known as the “Father of the Industrial Revolution.”

At 15 Edison began a career as a telegraph operator; although he was badly deaf from the age of 12 or so, he could hear clearly the clicking of Morse code, and he loved the telegraphist’s life as Mark Twain loved his steamboat days on the Mississippi. Not that this wandering life was long on comforts or even the common material decencies—of necessity his earliest inventions included an improvised rat-paralyzer and a cockroach-oxidizer. All the while he continued his solitary studies; a second-hand copy of Michael Faraday’s Experimental Researches in Electricity proved the teacher he had been waiting for, full of essential matter and blessedly free of hard math, demonstrating how mechanical energy could be transformed into electrical energy with the dynamo. His mind swarmed with schemes for improving telegraphic transmission, and in 1869 he secured his first patent, for a telegraphic vote-recording machine, which he was sure would make his fortune but absolutely did not sell: speeding up the legislative vote-counting process, the device would have interfered with the inalienable right of the minority to filibuster.

But big things were in store come 1870. With a friend, he formed the electrical engineering firm of Pope, Edison & Company in New York, and soon devised a “gold printer” that quoted gold and sterling prices by wire; they sold it to Western Union, and Edison got $5,000 of the $15,000 fee. A $40,000 personal payday followed—about $870,000 in today’s money—for an improved stock ticker, and he spent most of the new fortune within a month on equipment for his new manufacturing shop. The day he got married in 1871, stock tickers were so much on his mind that he left his bride at home and worked in his laboratory till midnight, when he remembered he now had other responsibilities. Work would always consume him, and in the clutches of an engrossing problem he would function for days on end, relying on catnaps on the laboratory bench and pretty well forgetting that he needed to eat to live.

Edison’s business dealings with the likes of Jay Gould, William Vanderbilt, and J. Pierpont Morgan wore him out, as he was whipsawed between rival telegraph companies interested in what use they could extract from him. He made enough money that he could decide to quit business and manufacturing and pursue the vocation he knew he was born for. So at Menlo Park, New Jersey, in 1876 he built “the first industrial research laboratory in America, or in the world, and in itself one of the most remarkable of Edison’s many inventions,” as Josephson writes. “[N]o one had ever heard of a man setting up a center of research, a sort of ‘scientific factory’ in which investigation by a whole group or team would be organized and directed solely toward practical inventions.” In due course he would build a more expansive lab in West Orange, New Jersey.

The inventions would pour forth from The Wizard of Menlo Park: a world-beating total of 1,093 U.S. patents for his career. Dos Passos’s list of Edison’s most amazing inventions actually scants the most amazing: what the Wizard called his “comprehensive system of electric light distribution,” which replaced gas lighting and revolutionized the nation. Josephson numbers the items in this seven-point program: “the parallel circuit; the durable, high-resistance light; the improved dynamo as a cheap source of electrical energy; the underground conductor network; the devices for maintenance of constant voltage by which current was made to reach distant lamps evenly; safety fuses and insulating materials; and, finally, lighting fixtures with keys to turn them on and off.” What made Edison was not the incandescent bulb—which he did not invent in any case, though he refined it to make it practicable—but rather this concatenation of innovations that brought electricity to multitudes.

With Edison’s inventive success it was inevitable that he would plunge once again into business. The Edison Electric Light Company and the United Edison Manufacturing Company, the latter comprising Edison Lamp and Edison Machine Works and Bergmann’s appliance manufacture (the latter a firm founded by an Edison mechanic who became a big-time entrepreneur), were consolidated into the Edison General Electric Company in 1889 under the financial direction of J.P. Morgan and the railroad baron Henry Villard, netting Edison $1,750,000 in cash and stock. By 1892 Morgan’s machinations edged Edison and his name out of the business, which became known simply as the General Electric Company.

Edison would admit, or proclaim, that he “lacked the commercial temperament,” and would say, “I always invent to obtain money to go on inventing.” At a celebration organized by Henry Ford in 1929 on the 50th anniversary of the first successful incandescent bulb, Edison was feted as “founder and father of the present industrial era” and “one of the greatest men who ever lived.” As Ernest Freeberg writes of this Golden Jubilee in The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America (2013), “Contemplating the final conquest of electric light in the culture, [Edison] promised Americans a future in which the setting sun presented ‘no obstacles’ to human activity…. Edison felt sure that this ‘mastery over the forces of nature’ was about to liberate humanity to pursue its ‘greatest development.’”

Holy Conquest

What then has this greatest development amounted to? What relation does remarkable technological advancement have to civilization, particularly to American civilization, and specifically to what was honored until quite recently as high culture?

Alexis de Tocqueville’s observations on “Why the Americans Apply Themselves to the Practice of the Sciences rather than to the Theory” (Democracy in America, Volume II, Chapter 10) have the pungency of an aristocratic mind offended by the crassness of the American push. “In a crowd of men one encounters a selfish, mercenary, industrial taste for the discoveries of the mind which must not be confused with the disinterested passion that lights up in the hearts of a few; there is a desire to utilize knowledge and a pure desire to know.” In America there are no men like Blaise Pascal, who, unmoved by profit or glory, focused “all the powers of his intellect in order better to discover the most hidden secrets of the Creator,” and whose spiritual fires burned so hot they effectively consumed his body before he reached the age of 40. Against such supreme mental heroism Tocqueville pits the rude vigor of democratic men who “dream only of the means of changing their fortune or of increasing it. For minds so disposed, every new method that leads to wealth by a shorter path, every machine that shortens work, every instrument that diminishes the costs of production, every discovery that facilitates pleasures and augments them seems to be the most magnificent effort of human intelligence.”

To Tocqueville, Edison would seem not so much an uncommon common man as a rather low type taken to the extreme, sweating away for all the wrong reasons, which is to say the customary democratic ones, devoting himself to a mental life concerned principally with the needs and the desires of the body—and not even his own body. If there is a redeeming quality to such as Edison, it is that he despises his own body’s comfort and pleasure as he labors furiously to facilitate and augment pleasures and comforts for the masses of men. With the pride of the thinking man he says, “I use my body just to carry my brain around.”

To Tocqueville, then, Edison would stand a cut above the average sensual man to whose gratification he bends his efforts, because his relentlessly active mind and ascetic temperament cause him to think nothing of sleeplessness or hunger. He is as faithful to the task in the laboratory as a nonpareil general is to his troops in the field—when he invented the prototype for the phonograph, he said the voice from history he’d most want to hear was Napoleon’s. Yet Edison is also a cut below the average sensual man because he serves the common appetite as a slave does his master; immense fame and wealth cannot make up for the essentially servile life he leads. Despite his lifelong passion for learning he proclaims only contempt for liberal education, the education designed to make a free man, which in his view fills a young man up with “Latin, Philosophy and all that ninny stuff. America needs practical, skilled engineers, business-managers and industrial men.” In three or four centuries there might be a place for literary men in America, he allows, but now is not the time for such diversions from the serious work to be done. Thus he declares himself essentially unserious and unfit to be mentioned in the same breath with someone like Pascal or Tocqueville himself. Or so one gathers from Tocqueville’s dark meditation on the practical American mind.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, in the peroration to the essay “Art,” published in 1841, the year after the second volume of Democracy in America appeared, announces that the noblest beauty of the future will be found in the mundane reality that currently seems beneath the notice of exalted spirits. “It is in vain that we look for genius to reiterate its miracles in the old arts; it is its instinct to find beauty and holiness in new and necessary facts, in the field and road-side, in the shop and mill. Proceeding from a religious heart it will raise to a divine use the railroad, the insurance office, the joint-stock company, our law, our primary assemblies, our commerce, the galvanic battery, the electric jar, the prism, and the chemist’s retort, in which we seek now only an economical use.” Men and women now ordinary will be transfigured by their new awareness of nature’s perfection in the objects of common life. “Is not the selfish and even cruel aspect which belongs to our great mechanical works—to mills, railways, and machinery—the effect of the mercenary impulses which these works obey? When its errands are noble and adequate, a steamboat bridging the Atlantic between Old and New England, and arriving at its ports with the punctuality of a planet, is a step of man into harmony with nature.”

For Emerson, the conquest of nature is a marvelous natural phenomenon, holy as all nature is holy; and the great technological advances are as conducive to wonder as the alpine peaks or thunderous waterfalls of the unspoiled continent, and probably more so than beautiful poems and pictures. America will lead the way toward the appreciation of mechanical magnificence. The tool designer and the industrial magnate will be honored as artists superb as Shakespeare and Michelangelo. Emerson is a world away from Tocqueville’s contempt for the grubby American mind. Emerson discerns the latent splendor in mental energies that Tocqueville finds unworthy, and he is confident that that splendor will be fully realized as American material civilization is perfected.

Emerson’s is a very different mind from Edison’s, but the philosopher and poet recognizes the genius of the inventors and businessmen that enable his own genius to flourish. As Emerson declared in his essay “The Young American” (1844), the American future, which will reconfigure the world through the pursuit of material interests, is cause not for dismay but for euphoria. “Gentlemen, the development of our American internal resources, the extension to the utmost of the commercial system, and the appearance of new moral causes which are to modify the state, are giving an aspect of greatness to the Future, which the imagination fears to open. One thing is plain for all men of common sense and common conscience, that here, here in America, is the home of man.” To be at home in this world, to be happy in the life man has made for himself right here, is the consummate human desire, and the triumph of the practical mind makes possible the concord between human nature and inhuman nature that will be the hallmark of civilization at the zenith. One may look back at Emerson’s vatic boosterism with irony but not with legitimate disdain; the ardent hope may be far from fulfillment, and may be receding by the moment, but it is no less beautiful for that.

Walt Whitman too saw American material progress in the service of the soul. In “Song of the Exposition” he hailed the arrival of the Muse on American shores, where she will find nothing like the stuff of classical epic or medieval romance:

Making directly for this rendezvous,

vigorously clearing a path for herself, striding through the confusion,

By thud of machinery and shrill steam-whistle undismay’d,

Bluff’d not a bit by drain-pipe, gasometers, artificial fertilizers,

Smiling and pleas’d with palpable intent to stay,

She’s here, install’d amid the kitchen ware!

Like Emerson, Whitman perceives a noble end for which industry and commerce, however far from noble they might seem, are the necessary means: “Think not our chant, our show, merely for products gross or lucre—it is for thee, the soul in thee, electric, spiritual!”

Electricity itself, the sine qua non of modern progress, nourishes the American soul and the All-American Muse. In Whitman’s “I Sing the Body Electric,” the body is not to be despised as an impediment to the everlasting glory of mind and spirit, as it was for Tocqueville’s Pascal; it is endowed with a majesty that encompasses the beautiful soul.

If anything is sacred the human body is sacred….

The beauty of the waist, and thence of the hips, and thence downward toward the knees,

The thin red jellies within you or within me, the bones and the marrow in the bones,

The exquisite realization of health;

O I say these are not the parts and poems of the body only, but of the soul,

O I say now these are the soul!

Whitman’s America sanctifies the whole human being, aglow as with electricity, which is harnessed to minister to human wants, the soul’s indistinguishable from the body’s.

His “Passage to India” opens with a celebration of modernity’s surpassing technological accomplishments, which are in the process of making mankind one:

Singing my days,

Singing the great achievements of the

present,

Singing the strong light works of engineers,

Our modern wonders (the antique ponderous Seven outvied,)

In the Old World the east the Suez Canal,

The New by its mighty railroad spann’d,

The seas inlaid with eloquent gentle wires….

The “eloquent gentle wires” of the transatlantic telegraph cable are a perfect touch: technology here is not only beneficent but gracious. But the time is long past for such idyllic talk. Nowadays, any human presence in the vast oceans is said to menace the delicate marine ecosystem. Supposedly so few wild places remain that they must be spared undesirable human encroachment. Great white sharks and giant squid are now sacred, perfect in a way men will never be; human beings defile and destroy. Inhuman nature is the environmentalist movement’s replacement for the human soul. Nature alone is holy but not in any sense Emerson or Whitman would have understood.

Flattening the Soul

More in keeping with the spirit of our age are works like David Mamet’s play The Water Engine: An American Fable, which appeared on Broadway in 1978. The play is set against the backdrop of the Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago in 1934, where the center of the show is the Hall of Science. As the barker enthuses, with the lyrical matter-of-factness of the sound democratic man,

Science, yes, the greatest force for Good and Evil we possess. The Concrete Poetry of Humankind. Our thoughts, our dreams, our aspirations rendered into practical and useful forms. Our science is our self. What are our tools, but wishes?

Charles Lang, a punch-press operator for the manufacturing firm Dietz and Federle, has “freed the hydrogen” in water and invented an engine that runs on the stuff. When he demonstrates the wondrous machine, the factory wage-slave states rather too hopefully, “There are no more factories.” He consults a lawyer about getting the patent for his device, and with this first wrong move gets caught in and torn to pieces by the machinery of corporate greed. The aptly named patent lawyer Gross delivers Lang to the aptly named Oberman, the lawyer for Dietz and Federle, which he says may claim that any patent lawfully belongs to the company, because Lang stole the tools and materials with which he built the engine from his employer. The company nevertheless is willing to make Lang an offer for his invention. The outraged inventor refuses. Thugs wreck Lang’s laboratory and his engine, but they cannot find the blueprints. Lang knows by now that the corporate interests want the plans in order to make sure the engine is never built; to them the prospect of no more factories is not a pleasing one. Lang tries to enlist a newspaperman in his cause but he is past all help by now. The journalist ends his day by phoning in the report of two bodies found tortured and drowned; it is clear the corpses are those of Lang and his sister. Nor will the devastation end there; for Lang had mailed the plans to the precocious young son of a candy store owner. As the boy and his father joyously plan an outing to the Hall of Science, the Barker’s reiterated spiel brings down the curtain.

David Mamet has made his reputation and his fortune with savage denunciations of the endemic corruption of American business, and The Water Engine shows him at his most angry and hopeless: we do not have the technology that would end human misery because the powers-that-be traffic in human misery. (Mamet’s youthful rage has reputedly cooled somewhat; like Dos Passos he has acquired a conservative crust with the passing years.) This is the stuff that puts warm bodies in the seats, on Broadway, in regional theaters, and at the movies. Today’s audiences love being revolted by commercial skullduggery, and the genius inventor sacrificed and the unknowing populace denied its rightful earthly bliss are just the ticket.

Another criticism of technology and business comes from Saul Bellow, who often cited Max Weber on the “disenchantment” of the modern world, the stripping of the magical or mystical forces that once constituted an invisible world as actual as the visible one. Bellow believed that these forces were as real as electricity, and that what we call reality is in fact a spiritual swindle; modernity’s known world leaves out immense soul-continents that were formerly common ground for generations of mankind—the believers whom we deride or pity as backward and benighted. Poetry, high art, is the vital remnant of that old-time religion, and its modern position is precarious. Bellow writes in his novel Humboldt’s Gift (1975), his tribute to his friend the poète maudit Delmore Schwartz, who flowered in his youth but died mad and broken:

Orpheus moved stones and trees. But a poet can’t perform a hysterectomy or send a vehicle out of the solar system. Miracle and power no longer belong to him.

Again:

And poets like drunkards or misfits or psychopaths, like the wretched, poor or rich, sank into weakness—was that it? Having no machines, no transforming knowledge comparable to the knowledge of Boeing or Sperry Rand or IBM or RCA? For could a poem pick you up in Chicago and land you in New York two hours later? Could it compute a space shot? It had no such power. And interest was where power was.

The extravagant promise vouchsafed by Emerson and Whitman has come to this, Bellow despairs. Material interests triumphant shall irradiate the soul with new powers? In Bellow’s canny judgment, Whitman and Emerson did not foresee that once that juggernaut of unstoppable progress got rolling, it would flatten everything in its way, beginning with the soul. So the only remaining magic is the technological magic that most modern men revere, and that is a poor simulacrum of the forgotten primordial beauty. Where poetry and philosophy were once in the exultant vanguard of the common American life, they must now conduct a rearguard action to save the most precious and most endangered portion of the human patrimony from the American way of life. To Bellow it looked as though, at best, they would go down fighting.

Sense of Wonder

So the question concerning technology is more complicated than how to convince people to turn off the lights when they leave the room. One must duly recognize the colossal contribution that Edison and men like him have made, not merely to the ease and comfort of modern life, but to its very possibility, to the vast distance we have come from the past, when cold and darkness and disease were insuperable. One must also recognize how far removed we are from the hopes of visionaries such as Emerson and Whitman, whose glorious future we now inhabit with so diminished a sense of joy and wonder at nature, and at the human efforts to conquer nature. Almost nothing amazes modern Americans, and especially modern American intellectuals—not even the techno-wizardry that Saul Bellow considered our golden calf. To recover the sense of wonder, at the works of nature and the works of man, the sky at midday and the city lights at night, is the urgent moral imperative.

And so the question concerning technology implicates the current disregard for poetry and philosophy, and not merely among the sort of people who have never had any use for them. Martin Heidegger writes in his essay that the Greek word techné encompassed not only technology but also “the bringing-forth of the true into the beautiful.” The great “danger” from modern technology and “the saving power” are thus joined at the root. The saving power may be hard to reach but it is always available. To be at home in this world which more recent mankind has made is our great challenge: to see whether Emerson and Whitman can survive all the modern conveniences.