Books Reviewed

Books discussed in this essay:

A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars, by Andrew Hartman

Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America, by James Davison Hunter

One Nation, Two Cultures: A Searching Examination of American Society in the Aftermath of Our Cultural Revolution, by Gertrude Himmelfarb

An Anxious Age: The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America, by Joseph Bottum

In 1993, after the USSR had dissolved and the Berlin Wall been pounded into souvenirs, Irving Kristol wrote, “There is no ‘after the Cold War’ for me.” Instead, the defeat of Soviet Communism signified only that “the real cold war has begun,” a multi-front civil war against the “liberal ethos,” which “aims simultaneously at political and social collectivism on the one hand, and moral anarchy on the other.” Kristol explained that he had come to believe that “rot and decadence…was no longer the consequence of liberalism but was the actual agenda of contemporary liberalism.”

The fight against collectivism hasn’t been won, but remains hard-fought and competitive. The end of the Cold War signaled the demise of socialism and central planning as ideals people fought for, or even took seriously. In 1997 the influential philosopher Richard Rorty chided his fellow leftists for their vague desire to repudiate and move beyond capitalism, despite failing to figure out “what, in the absence of markets, will set prices and regulate distribution.” Until the Left comes up with clear, compelling answers to such basic questions, he said, it should limit its ambitions to “piecemeal reform within the framework of a market economy.” As any Tea Party member assessing the Obama presidency will tell you, if liberals put enough piecemeal reforms together, the result is de facto collectivism. The existence of the Tea Party, however, and the fact that the Left is reduced to either denying its ultimate purposes or simply operating without any, constitute real achievements.

To believe the battle against “moral anarchy” has been equally close, with each side securing some victories while suffering defeats, would be delusional. This year’s Obergefell decision, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws means that no state has the constitutional power to deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples, is the most dramatic evidence of the culture war’s asymmetrical correlation of forces. That the liberal ethos would claim so much territory so quickly was beyond imagining in the 1990s.

Identity

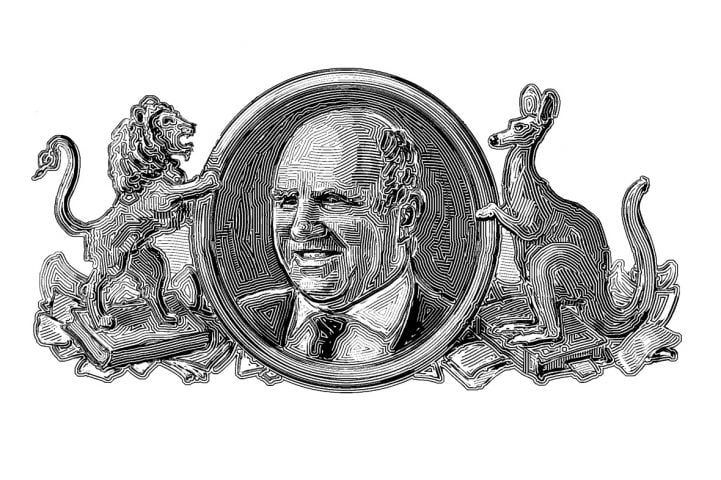

Irving Kristol was the leading neoconservative, and Patrick Buchanan neoconservatism’s leading “paleoconservative” critic. But in his 1992 speech to the Republican national convention (after unsuccessfully challenging President George H.W. Bush for the nomination), Buchanan characterized the political landscape in terms indistinguishable from those Kristol would later employ. The 1992 election, he said, “is about who we are” and “what we believe and what we stand for as Americans.” Conservatives, Buchanan said, were engaged in a war “for the soul of America,” one “as critical to the kind of nation we shall be as the Cold War itself.”

Andrew Hartman selected Buchanan’s phrase for the title of his history of America’s culture wars, A War for the Soul of America (2015). Others, of course, have written books on the subject. The first to attract wide attention beyond academe was Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America (1991), by James Davison Hunter. Hunter defined his subject in general as “political and social hostility rooted in different systems of moral understanding.” In most times and places such hostilities resulted from clashing religious beliefs. The tensions specific to the United States at the end of the 20th century, however, were different, involving “opposing bases of moral authority and the world views that derive from them.” These differences, not primarily sectarian, were animated by the tension between what Hunter described as the orthodox and progressive worldviews. Adherents of the former believe that the ultimate moral authority is “external, definable, and transcendent.” For the latter, “the binding moral authority tends to reside in personal experience or scientific rationality, or either of these in conversation with particular religious and cultural traditions.”

“Culture wars” is a metaphor, but not simply an exaggeration. “Culture politics” never caught on, for good reasons. War means sovereignty is at stake, which isn’t the case in ordinary political conflicts. Whose country is this?

This question is particularly important and difficult for America. For most countries, a distinctive identity is largely defined by “ethnonationalism,” as political scientist Jerry Z. Muller calls it. Winston Churchill appealed to it during World War II, for example, speaking to English audiences of “this island race.” America’s Declaration of Independence begins by stating that the time has come for “one people” to sever their connection with “another.” At a time when America and England were demographically similar, the basis for calling Americans one people was not a distinctive ethnic identity. It came to be a creed, of which the principles announced in the Declaration’s most famous passages figured prominently. As America has become more heterogeneous over the subsequent 239 years, the meaning of its creed has become steadily more important, since the possibility of unity on the basis of a shared ethnic identity has steadily dwindled. Thus, Americans’ disagreements about who we are turn heavily on what we believe and stand for.

Furthermore, accepting the possibility of a loyal opposition is especially important to a self-governing republic. Arguments about what we believe and stand for resemble war more than politics in that it is much harder to treat adversaries who differ about matters so fundamental as patriots in good standing. To put the point another way, questions about national identity are meta-political rather than simply political. It becomes hard for republican politics to be the medium through which we resolve our differences if the question of who we are is disputed rather than settled. Six years after Irving Kristol declared that “the real cold war” had just begun, his wife, historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, wrote a book about the culture wars, One Nation, Two Cultures. Its assessment of America’s predicament at the end of the 20th century concludes with the hope that the configuration described in its title is indefinitely tenable, but the book’s foregoing analysis does not make that outcome sound likely.

Finally, the arguments over cultural issues are bigger than republican politics by virtue of addressing the social prerequisites for such politics. Even as he praised, in The Federalist, the Constitution’s ingenuity in “supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives,” James Madison made clear that such devices amounted to “auxiliary precautions.” There was, by contrast, “no doubt” that a “dependence on the people” is “the primary control on the government.”

And if the success and safety of the government depend on the people, so that they’re depending on themselves, the people have to be good. No social contract, no matter how shrewdly devised, would allow the immoral and amoral to successfully govern themselves. In 1788 Madison told the Virginia convention considering whether to ratify the new Constitution:

But I go on this great republican principle, that the people will have virtue and intelligence to select men of virtue and wisdom. Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation.… To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical idea.

Edmund Burke expressed a similar view. “Men are qualified for civil liberty in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their own appetites,” he wrote in 1791. “Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without.”

Buchanan called the war for the soul of America a “religious war” and a “cultural war.” The two terms are not interchangeable, but their subjects are related. In a similar way, America’s founders, even those who were religious skeptics, believed that the moral foundations necessary for a successful republic rested on religious devotion. No matter how many hopes we invest in “the influence of refined education,” George Washington said in his Farewell Address, “reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

Counterculture

Hunter, whose Culture Wars appeared at the height of the culture wars, is a sociologist. Hartman, a historian, treats that war as basically decided, if not exactly over. The culture wars “are history,” he writes, now that their logic “has been exhausted.” Though his book offers narrative and analysis with limited polemic, there’s no doubt that Hartman believes the side that deserved victory is the one that did indeed prevail. In retrospect, he concludes, “A more tolerant and less sadistic society was worth winning.”

As Hartman portrays them, the culture wars were a fight between the 1950s and the 1960s, one so intense as to preoccupy America in the 1980s and 1990s. By “the 1950s” I mean what Hartman calls “normative America,” his term to describe “a cluster of powerful conservative norms” that shaped Americans’ sensibilities and expectations from the end of World War II in 1945 to President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. What the 1960s stood for in the culture wars was best summarized by historian Theodore Roszak in 1968: “the effort to discover new types of community, new family patterns, new sexual mores, new kinds of livelihood, new aesthetic forms, new personal identities on the far side of power politics, the bourgeois home, and the Protestant work ethic.” Or, as Hillary Rodham told her classmates at the 1969 Wellesley graduation, “our prevailing, acquisitive, and competitive corporate life…is not the way of life for us. We’re searching for more immediate, ecstatic, and penetrating modes of living.” The culture wars, then, pitted the counterculture against the counter-counterculture, which rejected the 1960s’ innovations as dangerous mistakes and sought to reestablish the 1950s’ standards of moral and political decency.

The term “normative America” may convey more than Hartman intends. Normative Americans believe in specific norms regarding family structure, sexual conduct, the best way to include ethnic and racial minorities in the larger society, and the worth and meaning of the American experiment. But they also believe that norms, per se, are good and necessary. Without them everything is up for grabs, rendering life contentious, chaotic, and debilitating.

As the statements from Roszak and Rodham make clear, however, the counterculture was always more counter than culture. Fundamentally oppositional, the counterculture forcefully rejected normative America’s precepts, but never offered real clarity about the standards of conduct and comity that should prevail after the old ways were discarded. As Hunter explains, orthodox America appealed to “definable” authority, while the progressive worldview relied on “conversations,” in which various sources of authority would all have their say without any getting the final word. The countercultural project, then, was not to establish a new set of norms to replace the old, but to create a society where people got along as well as possible with as few rules and expectations as possible.

Good People

Whether the live-and-let-live maxim was designed to bear that much weight is highly doubtful. Humans have an abiding need to feel at home and at ease in their particular society, to consider themselves members of one specific nation whose members are bound together by ties stronger than the reciprocal recognition of rights and duties. Little wonder that Joseph Bottum’s book, published last year, about how post-, anti-normative America understands itself is titled An Anxious Age. Bottum, an essayist who has been literary editor of the Weekly Standard and editor of First Things, examines the anxiety of those Americans who “need to see themselves as good people” in circumstances where there are few clear standards to define moral excellence.

As noted, the source of such norms for most of human history, and even for most of the history of a country as young as America, has been organized religion. Bottum’s subtitle—The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America—makes clear that he searches for our reigning standards in the residue of American Protestantism.

The decline of mainline Protestantism, according to An Anxious Age, is “the central political fact of the last 150 years of American history.” Bottum succeeds in making this hyperbolic claim sound at least plausible. By the mainline Protestants he means Baptists (outside the South), Disciples of Christ, the United Church of Christ, Episcopalians, Lutherans (except for a few small, severe offshoots), Methodists, and Presbyterians. The mainline could also be defined as the portion of American Protestantism distinct from, and averse to, fundamentalist or evangelical denominations and movements.

Mainline Protestantism was “our cultural Mississippi,” Bottum says. A Roman Catholic with a doctorate in medieval philosophy, he considers mainline Protestantism’s intellectual ambitions and accomplishments modest, but also thinks it was “all the Christendom we had in America,” providing “a vague but vast unity that stood outside politics and economics.” As late as 1965, the mainline Protestant churches’ members accounted for over half of all Americans, by Bottum’s account, but after “running out of money and members and meaning” for decades they represent only about a tenth today.

Societies may undergo eras of declining religious faith and observance, but that doesn’t mean people stop asking the questions religion exists to address. The desire for meaning, dignity, and purpose remains. Modern Europe is, by several empirical standards, further advanced into post-Christianity than the United States. Six years ago Charles Murray wrote in the Wall Street Journal that more and more of the Europeans he encountered believed, “Human beings are a collection of chemicals that activate and, after a period of time, deactivate. The purpose of life is to while away the intervening time as pleasantly as possible.” Hedonism may well be a growth stock, but for many people on both sides of the Atlantic, even those who take refuge in the “spiritual but not religious” dodge, life’s purpose is for the chemically active years to be satisfying rather than merely pleasant. Boys and girls may want to have fun, but not just to have fun. They also, as Bottum observes, want to regard themselves as good people, if only because when fun is life’s only purpose, even fun isn’t a lot of fun.

Thus, modern, “unchurched” Americans who don’t believe in much of anything still resist believing in nothing. To explain our post-Protestant condition, Bottum borrows a phrase from Flannery O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood: the “Church of Christ Without Christ.” He notes that in 1948 one author of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights called that elaborate code “something like the Christian morality without the tommyrot,” which deftly sums up a modern attitude toward the efforts across two millennia to comprehend the cosmos, our place in it, the meaning of our lives, and the knowledge those lives will end.

A New Faith

Bottum believes that our post-Protestant Church of Christ Without Christ, or of God Without God, lays claim to the same moral hegemony exercised for most of our history by the mainline Protestant churches. The crucial difference is that the post-Protestants have substituted a political agenda and set of social attitudes for the tommyrot of the Christian heritage. As a result, he wrote elsewhere, “Our social and political life is awash in unconsciously held Christian ideas broken from the theology that gave them meaning, and it’s hungry for the identification of sinners—the better to prove the virtue of the accusers and, perhaps especially, to demonstrate the sociopolitical power of the accusers.”

Bottum is hardly the first to point out the strong desire for secular substitutes for organized religion by those who have rejected religious faith. A 1949 collection of essays explaining the contributors’ decisions to become ex-Communists was titled The God That Failed. But Marxism demanded to be interpreted as a secular religion. It had its prophet and apostles; an account of man’s fall and salvation; its sacred texts and endless, maddening debates over their interpretation; a vision of earthly paradise; and for much of the 20th century the Kremlin was its Vatican, the Communist Party its one true church.

America’s more recent secular faith is far less coherent, organizationally and intellectually. What abideth is the disdain of the redeemed for the unredeemed, and especially for the unrepentant. The post-Protestants, whom Bottum also calls “the elect,” have rejected “benevolent toleration,” the “broad-shouldered acceptance of the fact that other people hold strong views we think are mistaken.” Instead, they prefer to “sneer at those who hold strongly particular views” rooted in religious faith, and revel in the “superiority of the spiritually enlightened to those still lost in darkness.”

The upshot is that sinners and heretics will be fiercely denounced, even though the commandments they violate are murky and a constant work in progress. Bottum argues, for example, that anti-racists’ preoccupation with white privilege serves all the same purposes as the doctrine of Original Sin. “I will carry this privilege with me until the day white supremacy is erased,” lamented one college professor. Similarly, novelist Jonathan Franzen, a political liberal and committed environmentalist, notes the “spiritual kinship of environmentalism and New England Puritanism.”

Both belief systems are haunted by the feeling that simply to be human is to be guilty…. And now climate change has given us an eschatology for reckoning with our guilt: coming soon, some hellishly overheated tomorrow, is Judgment Day.

The power of post-Protestantism is such, Bottum contends, that it has also come to define what’s left of mainline Protestantism. His take-away from reading some works by Katharine Jefferts Schori, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church of the United States, is that “God already loves us, just the way we are.” In her “happy soteriology such love demands from us no personal reformation, no individual guilt, no particular penance, and no precise dogma.” Instead, “all we have to do to prove the redemption we already have is support the political causes [Schori] approves. The mission of the church is to show forth God’s love by demanding inclusion and social justice.” The viability, religious or political, of an institution that offers itself to the world as the National Organization for Women or the Sierra Club at prayer is highly doubtful.

The Right to Define

Writers other than Bottum have called modern liberalism a kind of secular religion, but differ about this protean faith’s dogma, which they struggle to delineate. Rod Dreher says that the entirety of “moralistic therapeutic deism” amounts to: “God exists, and he wants us to be nice to each other, and to be happy and successful.” Yuval Levin argues that progressive liberalism has become so ambitious, comprehensive, and insistent in its demands on conduct and conscience that it amounts to an official religion, violating the spirit if not the letter of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. Others refer to the Church of Anti-Discrimination, or call Anti-Racism our new civil religion.

These assessments are not wrong, but neither are they encompassing enough to describe a belief system that is simultaneously latitudinarian about some questions, and righteously intolerant about others. I submit that the first and great commandment of our modern liberal faith is, “Thou shalt not judge.” And the second commandment is like unto it: “Thou shalt judge with harsh severity those who do judge, or who prejudge others, lest such bigotry impair its victims’ lives and psyches in ways unlikely ever to be undone.”

This creed clarifies several things about the way we live now. It comports with Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s famous dictum in a 1992 decision on abortion restrictions: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” That is, the only nature humans have is the nature they make by forging their own private ontology. Human nature, having no other essence, provides no objective standards by which we could determine whether to see ourselves as good people. There is only the solitary, sacred journey of self-discovery and self-definition.

It is unnatural, then, to judge others according to spurious criteria about what it means to act and live well or badly. All such judgments are not only unwarranted but harmful, a kind of human rights violation, depriving those whom we judge of the encouragement and esteem they need to pursue their own solitary quests. Prejudice, judging in advance, is a particularly odious transgression, since it may thwart victims’ life plans before they are even formulated—the abortion of a lifestyle, which is the only abortion that is unholy. It follows that the victims of bigotry—whether historic injustices that have enduring consequences, or discrimination still ongoing—have a special claim on our solicitude. We should feel guilty for failing to discharge our obligations to them, or for enjoying privileges made possible by past exploitations. And we should feel guilty, as Franzen suggests, about the harm inflicted by our gluttonous self-indulgence on those incapable of defending themselves: future generations, other species, the planet Earth itself.

The Sexual Revolution

Bottum’s post-Protestants “remain puritanical and highly judgmental” about many questions, but about one above all. They “understand Puritanism as concerned essentially with sexual repression, and the post-Protestants have almost entirely removed sexuality from the realm of human action that might be judged morally.” In this sense the Bill Clinton impeachment of 1998 was the battle that, while not ending the culture wars, proved that the conservative side could not win them. Shortly after Monica Lewinsky became famous, David Frum worried that the crux of the debate over Bill Clinton’s conduct would turn out to be “the central dogma of the baby boomers: the belief that sex, so long as it’s consensual, ought never to be subject to moral scrutiny at all.”

And that’s exactly what happened. The Clinton defenders framed the controversy as a case of bullying, hypocritical, sex-obsessed Javerts persecuting private conduct that, however tawdry and pathetic, was nobody else’s business. Even as the legal case that Clinton had committed perjury and obstructed justice grew stronger, the political sentiment that “lying under oath is a perfectly reasonable response to pesky and impertinent inquiries,” in Frum’s words, also became the prevailing consensus. As one of his defenders argued at the time, Clinton should suffer no formal consequences for “feeble fibs aimed at wiggling out of some horribly embarrassing but essentially victimless and legal piece of human stupidity.”

The failure—not just in Congress, but in the court of public opinion—of the Clinton impeachment revealed that the Moral Majority was not, in fact, a majority, at least not in the way the “religious Right” or “family values” advocates thought or hoped. After three decades, the sexual revolution had become the sexual status quo. The will and votes for a sexual counter-revolution simply weren’t there.

As it became clear that the sexual revolution was not going to be reversed, it became increasingly likely its logic would run its course. Eleven years before Obergefell, a Methodist pastor from Tennessee, opposed to same-sex marriage and the sexual revolution in general, read the handwriting on the wall. “When society decided—and we have decided, this fight is over—that society would no longer decide the legitimacy of sexual relations between particular men and women, weddings became basically symbolic rather than substantive,” Donald Sensing wrote in the Wall Street Journal.

Pair that development with rampant, easy divorce without social stigma, and talk in 2004 of “saving marriage” is pretty specious…. If society has abandoned regulating heterosexual conduct of men and women, what right does it have to regulate homosexual conduct, including the regulation of their legal and property relationship with one another to mirror exactly that of hetero, married couples?

In other words, the argument that same-sex marriage undermines traditional marriage would be compelling, logically and politically, if traditional marriage were still a robust institution. Given the actual state of marriage in 21st-century America, however, it has become increasingly difficult to persuade a society that has chosen in so many other ways to legitimize all consensual sex and trivialize marriage that this one particular, further concession to the sexual revolution must be resisted at all costs.

Thinkers such as Robert P. George and Ryan T. Anderson have in fact offered serious, sophisticated arguments against gay marriage. But syllogisms have been of little avail against sensibilities changing rapidly and, it seems, inexorably. In 2001, according to the Pew Research Center, Americans opposed same-sex marriage by a 57% to 35% margin. By 2015 the proportions were almost exactly reversed: 55% to 39% in favor; 70% of Americans born in or after 1981 now favor it, as do 59% of those born between 1965 and 1980. A nation where a large, growing majority of people have embraced this opinion without ever having been argued into it is unlikely to be argued out of it.

On one front of the culture wars, by contrast, the liberal ethos has met steady, even growing resistance. A 2012 USA Today/Gallup poll taken just before the 40th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision found that by a margin of 61% to 31% Americans believed abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy should generally be legal. Regarding second-trimester pregnancies, however, respondents believed abortions should generally be illegal by a margin of 64% to 27%, and were opposed to third-trimester abortions even more strongly, 80% to 14%. Those sentiments were virtually identical to results Gallup had received during the preceding 16 years. In 1995 56% of people described themselves as “pro-choice” compared to 33% who said they were “pro-life.” By 2015, the numbers were 50% and 44%, respectively. By margins consistently exceeding two-to-one, Americans favor specific restrictions, including a 24-hour waiting period, laws requiring girls under 18 years of age to get parental consent, and bans on partial-birth abortion.

Little wonder that Democrats felt compelled to take account of these sentiments, and sought political refuge in the formulation that abortion should be safe, legal, and rare. The pro-choice argument was an attempt to extend the logic of the sexual revolution: since consensual sexual activity should never result in unwanted criticism, neither should it result in unwanted consequences. The terms in which those who favor legal abortion have framed the question—privacy, a woman’s right to control her own body—begged the question of how to regard the fetus and define a decent society’s duties toward fetal life. The poll numbers reveal deep, persistent misgivings. There’s no consensus that abortion, especially early in a pregnancy, is the moral equivalent of infanticide. But there’s also no consensus that abortion, especially later in a pregnancy, is the moral equivalent of an appendectomy.

The abortion exception doesn’t go very far, however, in disproving the rule about the culture wars’ general course. The aptly named Reverend Sensing discerned that the sexual revolution had succeeded in placing consenting adults’ sexual conduct beyond government sanction or social censure. There’s every reason to think this assessment is even truer in 2015 than it was in 2004. The ambit of Americans’ don’t-tread-on-me defiance now extends to bristling at any judgments critical of consensual sexual behavior.

The Source of the Sixties

That a state of affairs appears irreversible does not mean it’s desirable or beneficial. The social regime established by the victorious sexual revolution may prove inimical to strong families. If so, how a nation without strong families sustains itself is not clear. A big reason the Religious Right entered the political arena in the 1970s, was that parents were exhausted and outraged at interceding constantly, 24/7, between their children and a corrosive, sexualized ambient culture. The goal was to remake the culture so that it respected their sensibilities, to secure a measure of deference comparable to that won by civil rights activists who got the book Little Black Sambo removed from school libraries.

This effort has to be judged a failure. Dreher reports on a couple he knows that recently chose to homeschool their children. Though happy with the public school, they could not abide that their son, a fifth-grader, had met friends who, away from class, routinely watched pornography on their cell phones. Dreher resides, not in Manhattan or Santa Monica, but in a small town in Louisiana.

Conservatives determining how, going forward, to resist the liberal ethos and moral anarchy need to consider their situation carefully. Doing so requires subjecting reassuring explanations of the culture wars to the strictest scrutiny, to avoid mistaking a comforting analysis for a compelling one. It has been congenial for conservatives to examine and deplore all the social problems caused by the 1960s: Robert Bork’s Slouching Towards Gomorrah: Modern Liberalism and America’s Decline (1996) was an effort difficult to surpass. But conservatives have had much less to say about the causes of the ’60s. What they did say concentrated on exogenous variables that had unbalanced America’s social equation. “New class” intellectuals, with belief systems foreign and antagonistic to the American way of life, were the prime suspects. The Moral Majority’s mission, accordingly, was to repel the Immoral Minority’s incursions.

The obvious difficulty with this explanation is its failure to account for, or even acknowledge, the anomaly of a previously robust civic culture’s sudden, ruinous susceptibility to the 1960s’ pathogens. Conservatives have found this theory of the case attractive, sticking with it through more defeats than victories, because it ascribes everything that was bad about the ’60s to “an alien distortion of the American tradition, rather than its plausible metamorphosis,” in the words of historian Mark Lilla.

To consider this latter possibility means grappling with the sobering idea that republics have, besides enemies, proclivities, some of which may turn a republic into its own worst enemy. Justice Kennedy’s startling formulation about defining one’s own concept of existence comes from somewhere, not nowhere, and that somewhere seems more inside than outside the American tradition. In Democracy in America Alexis de Tocqueville discussed the raw material that could result in such solipsism:

In the United States, even the religion of the greatest number is itself republican; it submits the truths of the other world to individual reason, as politics abandons to the good sense of all the care of their interests, and it grants that each man freely take the way that will lead him to Heaven, in the same manner that the law recognizes in each citizen the right to choose his government.

Democracy democratizes religion, making it less religious in the process.

In Revolt of the Elites (1994), historian Christopher Lasch called for “a revisionist interpretation of American history, one that stresses the degree to which liberal democracy has lived off the borrowed capital of moral and religious traditions antedating the rise of liberalism.” Like most of what Lasch wrote, that’s pretty gloomy, but maybe not quite gloomy enough. Borrowed capital implies the intention and capacity to make restitution, to generate new cultural resources that, even if different from the ones consumed, will adequately replenish the sources of stability and cohesion a society requires. If, instead, the normal course is for liberal democracies simply to use up the capital of moral and religious traditions, then democracy has a cultural contradiction for which there is no obvious solution.

Lasch agrees with Burke and the American founders that moral and religious capital generates political strength. It doesn’t follow that there is much politics can do to invigorate morality and religion. People are drawn to a religion because they find it consoling, inspiring, beautiful, and, above all, true—not because they think their faith will be politically useful to others. Democracy “has to stand for something more demanding than enlightened self-interest, ‘openness,’ and toleration,” Lasch wrote. But so do the lives of democracies’ citizens. If and when people who turned to moralistic therapeutic deism for spiritual nourishment come to regard that creed as a starvation diet, they are likely to seek out, or return to, more fortifying alternatives. In that sense, the serious problem of replenishing moral and religious capital may prove to be self-correcting.