Books Reviewed

A review of Poetry Notebook: Reflections on the Intensity of Language, by Clive James

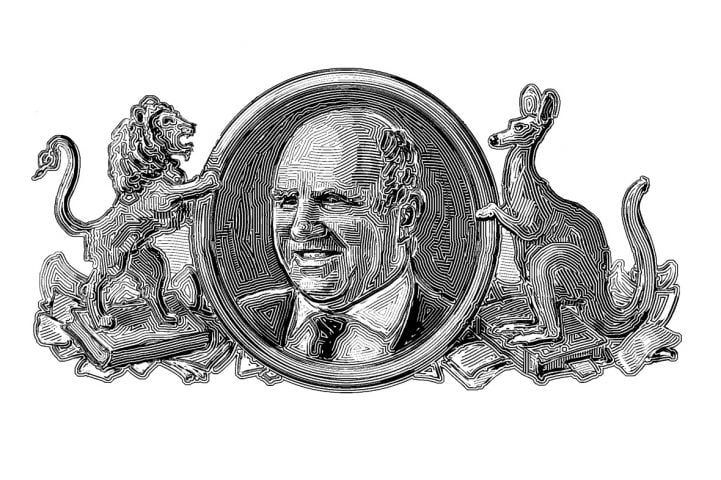

In a less politically correct era we would have called the witty Clive James “a man of letters,” but I must settle for calling him a leading poet, translator, novelist, memoirist, and critic. In his native Australia and in Britain—where James is a TV personality—he is a popular celebrity. At the age of 75 his time is short because he is suffering from leukemia and lung disease, his latest subjects for his self-deprecatory humor.

The genre of Poetry Notebook is one that I usually like as much as I would like foraging in a stranger’s refrigerator for leftovers: a collection of reviews and very brief essays originally published in journals. However, it engaged me as much as any book of poetry criticism since Mary Kinzie’s underappreciated 1993 book, The Cure of Poetry in an Age of Prose: Moral Essays on the Poet’s Calling.

Poetry Notebook originated in an arrangement with Christian Wiman, then the editor of the venerable journal Poetry, for which he asked James to write “miniature essays,” a kind of “bloggable” poetic diary. Alan Jenkins, the deputy editor of the Times Literary Supplement, later asked James to publish what became the final chapter of Poetry Notebook in his publication. The book also includes a few short pieces written for major newspapers and literary journals.

The brevity of each essay allows James to concentrate on “the intensity of language” with a passionate focus rarely seen in more conventional literary criticism. Its informality enables an imagined intimacy between the critic and his readers—I have never met the man, but I find myself thinking of him as “Clive.”

* * *

James overcomes the fragmentation of his book’s format by combining thoughtful close readings of our great (and allegedly great) poets with a cohesive critique of the poetry of the last century. Appropriately, he begins with his youthful falling out with Ezra Pound’s The Cantos, the cornerstone of modernist poetry, which cannot withstand the corrosive power of James’s close readings.

The typical deliberately gorgeous passage in The Cantos is working harder to be aesthetically loaded than a room decorated by Whistler, and time has added to the effect in just the same way. Something so perfectly in period acquires the pathos of freeze-dried evanescence.

In explaining his shift against Pound’s most famous work, James makes key points about Pound that most scholars know, but refuse to admit because of the consequences of such admissions for the modernist and postmodernist ventures. He properly credits the great expert in foreign policy and poetry, Robert Conquest, for being the first prominent scholar to insist that we cannot create a wall between Pound’s deranged political ideologies and his literary theories.

James notes (perhaps unfairly in Eliot’s case) that “it is often forgotten that it was Frost, and not Pound or T.S. Eliot, who really knew Greek and Latin” and that Pound’s Chinese was even sketchier.

For too much of his life, Pound was convinced that his grasp of Chinese was improving proportionately with the length of time he would spend gazing at the form of a character. But reading Chinese involves a lot more than looking at the pictures, just as understanding an economic system involves a lot more than analysing the metallic composition of its currency. Pound was convinced that he could assess whole countries, periods, empires, and eras by whether and how much their gold and silver coins were debased. Even as late as Canto 103 of Thrones he can be heard saying, “Monetary literacy, sans which a loss of freedom is consequent.”

He also criticizes Pound’s “faith that a sufficiently gnomic utterance will yield an unswerving truth” and the solipsism underlying Pound’s undeniable defense of anti-Semitism in The Cantos. James’s prose is invariably civil even when its conclusions are harsh, so one must infer that James is criticizing not only Pound, but the contemporary academics who refuse to stare at their iconic Pound in a clear-eyed way.

James insists on technique and insight from other poets. Notably, he takes on William Carlos Williams:

…the culprit was William Carlos Williams. When he realized, correctly, that everything was absent from Whitman’s poetry except arresting observations, Williams, instead of asking himself how he could put back what was missing, asked himself how he could get rid of the arresting observations.

Williams is not alone. James observes that Tony Harrison, “famous for composing in couplets, mangles them almost as often as he gets them right.” He is also dismissive of John Ashbery’s work except for “Daffy Duck in Hollywood,” an exception that I have to admit I find baffling.

* * *

It would be wrong, however, to view James as a full-throated critic of modernism, because he demands equally from all poets the brief transcendence created by skilled language fused with ambitious thought. Eliot’s “informal poems” not only escape from James unscathed, they receive sincere praise for “moments…many and unforgettable.” He comments favorably on many other free-verse poets, particularly James Wright and Gregory Corso. As for Sylvia Plath, he goes so far as to say that she “was working miracles.”

It is true that the poets who most excite James are the masters of formal technique. His five favorite poetry books are W.B. Yeats’s The Tower; Robert Frost’s Collected Poems; W.H. Auden’s Look, Stranger!; Richard Wilbur’s Poems 1943–1956; and Philip Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings. Although James revels in the striking phrases of these poets, he also has an engineer’s desire to reverse-engineer their great poems to see how they work. This tendency explains some of his unusual, but marvelous, phrases to describe a line, such as the “ignition point for attention.” It also explains the passage in which he praises Auden as a “test pilot” for the innovative machinery of poetry.

Despite his enthusiasm for formalism in poetry, James is unafraid to call out his fellow formalists—as when he cracks that “Frost’s celebrated gibe about formless poetry—tennis without a net—rings hollow, and not just because it has been repeated too often by solemn traditionalists.” He even questions Milton’s greatness: “Milton trained himself from early on to clog any passage of his verse with learned references.” He dismisses the “later Lowell” as “weak when tested by the intensity of the early Lowell” and observes that nobody “except a prisoner serving a life sentence learns Wordsworth’s ‘Immortality Ode’ by heart.”

* * *

James does not restrict his gaze to poets who are already famous, and he argues for those he believes should be part of the canon. He makes his most impassioned case for Michael Donaghy, a charming and distinctive genius who died 11 years ago at the age of 50, just as he was hitting his stride.

Devoid, on paper at least, of malice or professional jealousy, he could nevertheless quote a dud line with piercing effect. Robert Bly thought he was being profound when he wrote: “There’s a restless gloom in my mind.” Donaghy could tell that whatever was happening to Bly’s mind at that moment, it wasn’t profundity…. He was always searching for the language that had reached a satisfactory compression and power of suggestion. (It didn’t have to come from “the tradition,” or even from a poem: he was a close listener to song lyrics, playground rhymes, and street slang.)

James plumps with similar vigor for Samuel Menashe, one of the few contemporary poets who write in the vein of Emily Dickinson. He also makes a strong case for overlooked virtues in the verse of Louis MacNeice and John Updike. These arguments rely heavily on populist assumptions about the importance of accessibility of thought as well as the beauty of rhythms and sounds; for James true poetry belongs primarily to lovers of the traditional craft, not to academics, whom he views as tending to overvalue whatever is exotic, trendy, and obscure. His hard shot at Harvard’s Helen Vendler for her disparagement of Robert Frost is just one example of his wariness of the influence of the academy on the poetry he loves.

* * *

Poetry Notebook has a few minor flaws, for which I hold responsible Don Paterson, the prominent British poet who served as the editor at Picador for the 2014 British edition of this book. Both editions include a handful of largely redundant one-pagers that he should have excluded or asked the author to incorporate into adjoining essays. More importantly, this densely packed 256 pages of criticism lacks an index. To compound the problems created by that omission, James’s comments on any particular poet or topic are scattered throughout essays that, for the most part, lack helpful titles. If one wants to learn about James’s thoughts on Dorothy Parker, Carol Ann Duffy, Elizabeth Bishop, Louis MacNeice, or Robert Conquest (as one should), the titles do not help at all, and thus it is easy to miss important insights because of the lack of the easy fix of an index.

My only serious substantive criticism of Poetry Notebook is that I found James’s praise for his Australian peers to lack the clear-eyed vision of his other writing. A.D. Hope, Les Murray, Peter Porter, Stephen Edgar, and James McAuley are all fine poets, but Murray is not at the Nobel level as James suggests; one suspects that a generosity of spirit caused by friendship or patriotism has caused upgrades in James’s assessments of his countrymen. Or perhaps humility was the more likely culprit—it has to be impossible for James to assess contemporary Australian poetry when he is the Australian poet who has made the widest impact, and he is the one who has the best chance of enduring as a poet who matters.

Godspeed, Clive.