Books Reviewed

Was John Brown insane? That seems to be the only question people find worth asking anymore about the legendary abolitionist, and the answer has usually been that he was. Brown’s defense lawyers tried to plead insanity to spare him the death penalty, and the affidavits they collected from Brown’s one-time neighbors were studiously lined up to present a picture of a “deeply religious” and “very conscientious” man who was, at the end of the day, “clearly insane.” The plea was not of Brown’s design, and the old man gave it the lie with a serene and eloquent speech before the court, justifying his bloody raid on the Harper’s Ferry arsenal. Nevertheless, the insanity charge stuck, partly because it suited slavery’s sympathizers to associate abolitionism with insanity, and partly because it allowed anti-slavery Northerners to distance themselves from Brown’s way of dealing with slavery. Even Frederick Douglass, who professed to admire “Captain John Brown” as “one of the most marked characters and greatest heroes known to American fame,” quietly tiptoed away from any involvement with Brown at Harper’s Ferry.

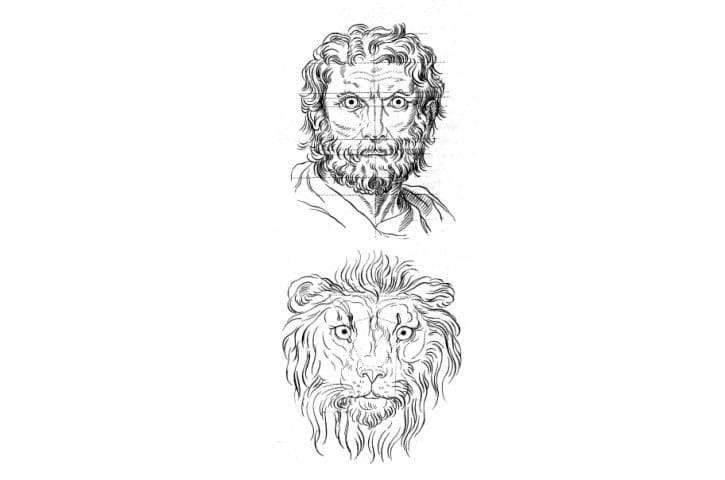

That was enough for the historians and biographers: Bruce Catton’s wildly popular Civil War histories dismissed Brown as “unbalanced to the verge of outright madness,” and Allan Nevins, writing in the fourth volume of his series on The Ordeal of the Union, thought Brown suffered from “reasoning insanity, which is a branch of paranoia…marked by systematized delusions.” The case was clinched visually by the great muralist, John Steuart Curry. Commissioned to paint a gigantic series of panels on Kansas history for the state capitol in Topeka, Curry cast Brown in the dead center of The Tragic Prelude, a gigantic figure of cyclonic rage, with an open Bible in one hand and a rifle in the other, maniacally egging Northerners and Southerners on to fratricide. Kansans were horrified at Curry’s depiction of Brown (who was, after all, one figure from Kansas history everyone had to learn something about) as a lunatic, but the image stuck.

The Curry mural adorns both the dust jacket and front matter of Merrill Peterson’s new book, John Brown: The Legend Revisited, but the actual message Peterson delivers is much more mixed. Like Peterson’s The Jefferson Image in the American Mind (1960) and Lincoln in American Memory (1994), this is a book about how history—in this case, the history of John Brown—is confected from an unstable brew of remembrance, wish, symbol, politics, research, and culture, and ends up differing from legend by not much more than name. Reflections of this sort used to take the more humdrum shape of bibliographical essays or historiographical surveys, describing and categorizing the views and interpretations of other historians and biographers. But pessimistic postmodern reductionism makes this impossible. It reduces evidence, records, and a broad variety of objects, rituals, and entertainments to texts, and thus blurs the line between history (which emerged from the hands of Hume and Gibbon as a proto-science) and memory (a wickedly subjective mental event whose nature was, as the Freudians testified, to invert, transfer, disguise, and repress). The history and historiography of John Brown can therefore no longer be safely located in any conventional narrative; they have become a legend. Hence, the subtitle.

Peterson is one of those historians who came of age in the era when American history became a casualty of its own optimism. The Depression savaged the faith American historians since James Ramsey and George Bancroft had had in the westward course of Whiggish empire; in the 1950s, the militantly disenchanted turned toward naïve versions of Marxist reinterpretation, and in the 1960s the rest were shunted in the direction of social history, a kind of New Labour account of human events that focused on “everyday lives” rather than “great men.” But anyone occupying an endowed professorship in an American university who advertised himself as a “Marxist” deprived himself at once of any reason to be taken seriously; and social history, although it had the virtue of relentless empiricism, required doing numbers and running regression analyses on aggregate samples, and this was precisely the stuff most history majors had gotten into the business to avoid. All this, at just the moment when university administrators were disconnecting the life-support of humanities programs unless those programs served the needs of more employable parts of the student body, like journalism majors or chemical engineers. Postmodernism came in the ’90s like a sweet wind of relief—it released historians from the grimy business of sorting and sifting the debris of social history to contemplate the evolution of “memory,” which requires much less hand-washing. And by denying that historical actors and historical authors had any control over what others made of them, it allowed underfunded and over-adjuncted history departments to cock a snook at what everyone else in every other department imagined were hard, verifiable, and profit-making facts. It was all just memory.

Peterson has never taken to reducing everything to memory. Lincoln in American Memory devoted much of its length to a fairly conventional review of the Lincoln biographical literature, and in this book (which is less than half as long as Lincoln in American Memory) Peterson is just as cautious. But Lincoln in American Memory did stretch the canvas of Lincolnian data to include Lincolnian fiction, political cartoons, insurance advertisements, and museums, as well as the usual battalions of warring biographers. And he began the Lincoln book, not with Lincoln’s life, but with his death, as if to say that no history of Lincoln’s life was any longer possible, only investigations of his place in the collective memory of Americans. In this book, Peterson gives the historical a little more of its due, since it begins, not with Brown’s death, but with Brown’s capture in the Harper’s Ferry arsenal. Nevertheless, “old Brown” is hanged and buried by the time the first chapter is done, so Peterson is once more free to deal with the various ways in which John Brown goes marching on as a memory rather than a life. The second chapter, “The Faces and Places of the Hero,” reviews legends and icons from Brown’s execution and burial. After that, the chapters are about books, articles, and biographies, with some attention to statuary and paintings (like Curry’s). At the end, Peterson is unsure whether Brown still possesses much purchase on American memory, and he offers no judgment on whether Brown was “insane.” But based on a recent up-tick of interest in Brown as a kind of Frantz Fanon of American slavery, he finally concedes that Brown seems “still to have a future in American thought and imagination.”

Failing to deal frankly with the insanity plea is a serious oversight, I think, because a great deal more than meets the eye hinges on whether we should regard the incidents which earned Brown his notoriety—the murder of five pro-slavery Kansans in 1856, raids on slaveholders and slaveliberation attempts in Kansas and Missouri, and the final, botched raid on Harper’s Ferry—as the acts of a clinical delusionary. As Peterson shows us, this has by no means been the consensus we might think it has been. The abolitionists thought that Brown “made the gallows as glorious as the Cross,” and sympathetic biographers—James Redpath, Franklin Sanborn, Oswald Garrison Villard—sprang up to exonerate Brown from the Kansas killings and extol the Harper’s Ferry raid as the first, necessary blow of the war against slavery. Looked at from a coldly military calculus, the notion that Brown’s little band of twenty-two could descend on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, strip it clean of weapons, and high-tail it into the mountains, where legions of the oppressed would flock to join him, really does seem like a madman’s plan. But looked at under the shadow of Nat Turner’s revolt in southeastern Virginia in 1831—or even more threatening, under the shadow of San Domingue in the 1790s—it looked like the secret plan Southerners always dreaded a Yankee would discover. (Brown, moreover, had surveyed the western Virginia mountains in an earlier career, and believed he knew the topography reasonably well). Then, in the 1940s, the late Herbert Aptheker found in Brown a “sense of class” and a rage against the capitalist order which had impoverished him in his many, unfruitful business ventures. Aptheker’s Brown seizes on slavery as the ultimate example of class oppression, and marches off to Harper’s Ferry with a Leninist vanguard to bring down, not only slavery, but the entire structure of capitalism. Seen through Aptheker’s eyes as an unabashed American Communist, Brown was an example, not of madness, but “genius.”

Yet another argument in favor of Brown’s rationality came in Stephen B. Oates’s To Purge This Land With Blood:

A Biography of John Brown in 1970, which resurrected Brown’s stark Cromwellian Calvinism as sufficient explanation for Brown’s murderous rampage through Kansas and Virginia. Never mind that Oates had a poorly-developed ear for Calvinist rhetoric—he mistook a listing made by Brown’s daughter of the first lines of Brown’s favorite hymns for the lines of a hymn itself—and that his reputation as a biographer was tarnished in later years by allegations of plagiarism (which he denied). He was certainly on to something.

* * *

Brown was born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, in the heart of the old New Divinity country of western New England. The New Divinity was the offspring of Jonathan Edwards, and the formulation of Edwards’s two most important disciples, Samuel Hopkins and Joseph Bellamy. The New Divinity theology ratcheted-up the demands of divine sovereignty and human accountability to such a pitch of immediate and perfect absolutism that it emotionally broke its listeners. “There can be nothing to render it, in any measure, a hard and difficult thing, to love God with all our hearts,” wrote Joseph Bellamy, “but our being destitute of a right temper of mind…therefore, we are perfectly inexcusable, and altogether andwholly to blame, that we do not.” Charles Grandison Finney, who was born in nearby Warren, Connecticut, preached that if sinners “were truly willing to give up sin, and all sin, they would not hesitate to pledge themselves to do it, and to have all the world know that they had done it.” Delay “was only an evasion of present duty,” and “all efforts” by sinners to perform that duty “while they did not give their hearts to God, were hypocritical and delusive, and no doing of duty at all.” This did not make the New Divinity popular with the commercial classes. The New Divinity preachers prided themselves on the tiny, rural parishes they pastored; Finney tried to set up shop in New York City, but fled in the 1830s to Oberlin, in eastern Ohio, which had been recently set up in the forests by New England expatriates who longed to rebuild the covenanted towns of their Puritan forebears. They were moral absolutists, with a derisive contempt or the materialism of commercial America—which included slavery. Parsing the recondite theology of the New Divinity was beyond Oates, and it even emerges ill-shaped and obscure from the most recent study of Brown’s religion, Louis A. DeCaro’s “Fire From the Midst of You”: A Religious Life of John Brown. But the connections between Brown and New Divinity Edwardseanism are too suggestive to ignore. Brown’s father, Owen, was converted to anti-slavery after reading a tract by one of the Edwardseans. Brown followed the arc of this movement himself to Ohio, and swore his first oath to destroy slavery under the preaching of a New Divinity expatriate in Hudson, Ohio.

In the 1990s, Brown found a new set of champions in racial identity politics, as the white man who repudiated “white” racial identity. “Whiteness” was as much a construction as black racial stereotyping, argued David Roediger, one of the apostles of “whiteness studies,” who lauded Brown in the attitude-driven quarterly Race Traitor. It was just that whites assumed that their construction, “whiteness,” was not a racial identity at all, but a certain generic, “normal” human-ness or American-ness. This self-deceiving psychological device allowed whites to profess all manner of good intentions and innocent hearts on the subject of race, while continuing to enjoy the invisible privileges attached to being white in America. Brown was the exemplar of a white man who deliberately decided to forgo those privileges, identify himself with the plight of blacks, and eventually resort to violent direct action on their behalf. He had, as John Stauffer has written inThe Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (a composite biography of four leading abolitionists that includes Brown) made himself “a black heart” that allowed him to forge “interracial bonds of friendship and alliance.” And so Harper’s Ferry was an expression of racial solidarity, not insanity.

Notwithstanding all these efforts to inject sanity, consistency, and even heroism into the image of John Brown, there is still this strange persistence in regarding Brown as insane, and a moment’s reflection will show us why. Aptheker was right to sense in Brown a boiling resentment against the rise of market capitalism, but wrong in seeing only that as the engine of Brown’s complaint against slavery. The New Divinity’s ferocious attack on self-interest, its single-minded unwillingness to weigh losses and benefits, and its nostalgia for the common life of the New England town also fueled that resentment and revealed to Brown an American landscape plagued with false freedoms, a false system of material values, and an acquiescent and abject retreat by the churches from the direction of public life. Like the abolitionist politicians who believed that a “Slave Power” had insidiously seized control of the federal government, Brown fixed on slavery as the moral power which had corrupted the American soul. His ideal world was a kind of egalitarian theme park in which inept wool merchants like himself never suffered devastating losses or never lost money in banks that closed—something which he actually came close to realizing (as Stauffer points out) when the wealthy abolitionist Gerrit Smith invited Brown to organize a racially-integrated community on Smith’s vast property holdings in upstate New York. But Brown was no better at organizing community life than commercial life. He yearned, as he had been taught to yearn by the New Divinity, for the act of ultimate submission, of death and martyrdom. And he found it, not at Harper’s Ferry, but at the trial which followed.

We would like Brown to have been insane because a looney John Brown is a harmless John Brown. Defining Brown as a madman dissolves the monstrous threat he would pose to the ideal of liberal society, because maniacs are mostly harmful to themselves, and that restores tidiness and predictability to our world. A liberal society is a society predicated on the use of reason, rather than religion or inherited status, in ordering human affairs. But when liberal democracies are confronted with movements which operate on totally different bases, it is entirely too convenient for Lockean liberals to write them off as a kind of pathology, since this relieves us of the burden of further investigation and the costs of further confrontation. This was why we allowed the proto-fascist Calhounites, who had their own delusions about mint-julep paradises to peddle, nearly to smash the republic into shards for the sake of white racial supremacy—slavery was a Southern thing, and had to be left to Southerners to work out, right? This is how we ignored Hitler—he was insane, too—and that miscalculation induced us to rationalize away any need to deal with the Nazi horror until it actually pressed the knife to our throats. This is also how we ignored Islamic terrorism—it’s a clash of civilizations, remember?—and so the Western democracies went their fat, dumb, and happy way, chuckling over the ridiculous incantations of the mullahs, until their disciples flew passenger jets into our skylines. Or worse still, this is how we dodge the need to respond to September 11, by bleating that the act was insane and requires an understanding, not of the act, but of the oppressive circumstances of post-colonial life which drove “them” to it.

Only at the end of John Brown: The Legend Revisited does Peterson raise the uncomfortable possibility that, if Brown was not insane, then the nearest modern comparison we must make to Brown is Timothy McVeigh. But even in this, Peterson does not hold us nearly as close to the fire as he should. Brown’s unslakable thirst for violence and his rage at the modern belongs beside the anarchists whose reign of assassinations followed Brown in Europe and America by only three decades; beside the “devils” in Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed and the Paris Commune; beside Hamas and Hezbollah. They were not—are not—insane, and neither was Brown, and we underestimate their rationality very much at our peril. Whether, after a century’s long slumber in the arms of pragmatism, liberal democratic society is capable of meeting that challenge, instead of hitting the snooze bar and calling the pounding on the doors below “insane,” will be the story of the next decade.