Books Reviewed

How do you shake a modern college graduate out of his comfortable liberal assumptions? How do you suggest to your average 22-year-old, raised in a secular and materialist society, that faith and tradition might not be mere forms of oppression or facile superstitions? Or that freedom might mean more than personal autonomy? You don’t simply hand him a copy of Saint John Henry Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua, and wish him Godspeed. Instead, you lead him gently. You explain to him that the dissatisfaction and dislocation he senses among his peers is real, and that there is a better way to live. Above all, you tell your young listener that he is not alone—that indeed, he is surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses.

This is how Sohrab Ahmari, a prominent conservative commentator and the opinion editor of the New York Post, reaches out to younger generations in The Unbroken Thread: Discovering the Wisdom of Tradition in an Age of Chaos. The book is an extended, carefully worded invitation to share in the treasures of Western civilization. Ahmari explains in the introduction that he is writing partly for his young son, Max. Max is named after Saint Maximilian Kolbe, a Catholic priest who gave his life for a fellow prisoner at Auschwitz and, in so doing, “climbed the very summit of human freedom.” Ahmari worries that Max, despite his illustrious namesake, will be surrounded by peers and teachers who take no thought for the things of the spirit: “What kind of man will contemporary Western culture chisel out of my son?” he wonders. “Which substantive ideals should I pass on to him, against the overwhelming cynicism of our age?” The Unbroken Thread invites Max, and by extension all young people, to embrace tradition, religion, and moral philosophy—in short, everything that modernity has declared pathological, superstitious, and irrelevant. At the very least, Ahmari hopes readers will reconsider what modern society says about the place these older values should have in our lives.

* * *

Each chapter presents a straightforward, timeless question that Ahmari believes a “confident, progressive modernity should readily be able to answer.” These include “questions about the nature and scope of reason; our responsibility to the past and the future; how and what we worship; and how we relate to each other, to our bodies, and to suffering and death.” In each case, material science and commercialism fail to answer these questions, but faith and tradition succeed. Ahmari is known for his forceful critiques of modern liberalism. But in The Unbroken Thread, he doesn’t rail against the inadequacies and absurdities of our degraded era. Instead, he approaches the big questions gently and indirectly, by introducing his readers to figures from the past whose lives and work demonstrate the inadequacy of a purely secular, hedonic approach.

In keeping with his pedagogical aim, Ahmari begins with someone his audience may have heard of, if never read: the popular Christian apologist C.S. Lewis. Ahmari explains who Lewis was, when and where he lived, and what he was trying to say. Then he walks us through Lewis’s famous science-fiction novel, Out of the Silent Planet (1938), to show how Lewis questioned the prevailing wisdom of his time and still of ours. Through his discussion of Lewis’s work, Ahmari suggests that there is a limit to what science can reveal, and that other kinds of knowledge—in particular moral knowledge—are necessary for human happiness. As Ahmari’s book progresses, we move beyond better-known authors, like Lewis and Saint Thomas Aquinas, to more obscure figures, like the civil rights leader Howard Thurman and the anthropologists Victor and Edie Turner.

* * *

The Unbroken Thread has been widely reviewed and praised, but it is not for everyone. Indeed, to understand its purpose, and even its form, you must understand its target audience. It is not for Ahmari’s peers in the conservative press, or the parishioners at a Latin Mass. It is for Max, and for all those with a nagging sense that something is not right in the modern world. Ever-greater numbers of high school and college students have never even heard of Aquinas or Augustine—to say nothing of Seneca or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. They are starting from nothing. Ahmari is trying to introduce them to a vast repository of received wisdom about how to live, how to think, and how to become truly free. As a hermeneutic device, this doesn’t always work. The ideas of Aquinas and Augustine, for example, are too dense for the kind of easy summation Ahmari wants to provide. Nevertheless, those chapters work well enough to serve their purpose, which is to coax that 22-year-old college graduate into a reevaluation of modern liberal assumptions.

In the last analysis, this book belongs to an emerging genre that might best be described as a kind of Ark, preserving the ideas of the past from the obliterating deluge of modernity. Think of Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option (2017), which urges Christians to reorient their lives around rigorous religious practices—at the expense, if need be, of engagement with secular culture. Or Jordan Peterson’s popular recent books, 12 Rules for Life (2018) and Beyond Order (2021), both of which advocate a radically countercultural way of thinking and living through deep engagement with the wisdom of the past. “Pick up your responsibility, pick up the heaviest thing you can and carry it,” Peterson often says to rapt audiences of young men. Why are they rapt? Because they have never heard anyone say these things before, and they are starving for wisdom.

* * *

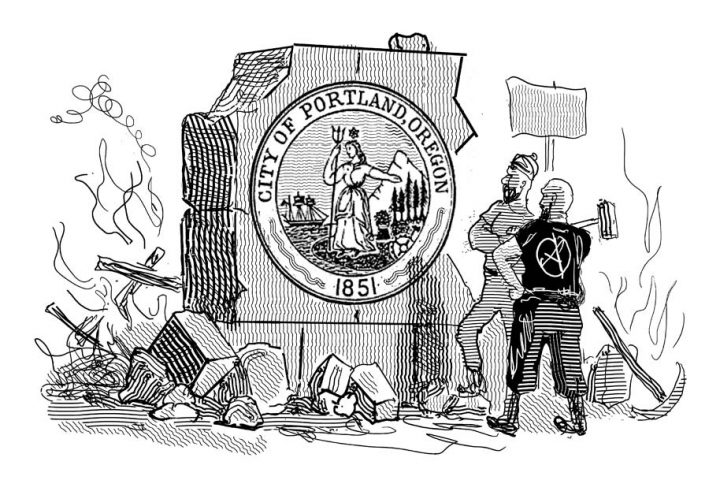

All these writers and thinkers, while different in their approach and tone, are working on a kind of remedial revival. They are inviting disaffected liberals, whether Christian or not, back into the richness of faith and tradition. In so doing, they are also preserving some essentials of the Western inheritance, laying them aside for a future when they will be needed to rebuild a society hollowed out by radical liberalism’s false promises. In face of the utter wreckage wrought by the sexual revolution, for example, we need to be able to answer one of Ahmari’s most urgent and provocative questions: is sex a private matter?

Ahmari answers in the negative. His chapter on sex stands out not just because it introduces readers to a figure they have likely never heard of (the feminist writer Andrea Dworkin), but because it criticizes both liberals and conservatives who would restrict sex entirely to the private sphere. Ahmari’s treatment of this question shows just how deep his critique of liberalism really goes. He is not concerned with quibbling about the excesses of the sexual revolution: he is launching a frontal assault on its core tenets. Using both Dworkin’s rather tragic life story and her work as a literary critic, Ahmari challenges his reader to justify one of the most sacred liberal pieties: that sex is a private matter, just harmless fun.

It is neither, Ahmari insists. He cites first Dworkin, then Saint Augustine, whom Dworkin also cited approvingly (though she was certainly no Catholic). Sex and lust, Ahmari argues, are bound up together. This presents problems for any society, but especially one that insists men and women should be equal—since too often when it comes to sex, they are not. Women are frequently objectified and victimized by men. This is why traditional societies placed barriers and restraints around sex: not out of a prudish or authoritarian impulse, but to protect women and preserve families. This is a rebuke both to liberals and to certain kinds of self-styled conservatives, writes Ahmari:

If Dworkin’s diagnosis was mostly correct—and the daily #MeToo headlines suggest it was—then the best we can do might be to begin rebuilding some of the barriers foolishly torn down by our parents and grandparents. “Conservative,” religious Americans should set aside their reflexive hostility to all things feminist and resist the temptation to treat a sexist, boorish, and essentially libertine ethic of relatively recent vintage as somehow ordained by Scripture, antiquity, or “nature.” By the same token, feminists and men and women of the “left” would be wise to take a second look at tradition rightly and broadly understood, as a source of sexual restraint and regulation, ordered especially to the protection of women and children.

By now it should be obvious that Ahmari is after something more than a revival of live-and-let-live libertarianism, or a private, quiescent conservativism. He is arguing that if we want to rebuild in the wake of our present crisis, we’re going to need stronger stuff. We are going to need the faith and traditions of the past, in all their complexity and profundity, and we are going to have to explain them to a generation that is encountering them for the first time. That is what his book is about. It is, as it were, a procession of animals, some of them exotic and dangerous, some from far-flung lands, walking aboard an Ark under a darkling sky. Under the circumstances, whatever quibbles one might have with Ahmari’s method or style are not all that important. The rain is falling hard now, and the waters are beginning to rise.