Books Reviewed

Of the writing of books on Islam there is no end. Several hundred have appeared in the U.S. in the last two years. Most of them can and should be ignored except as a way to learn of the dismal state of American thinking on the subject. However, there are a few gems.

John L. Esposito gives us one non-gem. Esposito, the University Professor of Religion and International Affairs and director of the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University, was a foreign affairs analyst for the Bureau of Intelligence and Research in President Clinton’s State Department. One of his hallmarks is a penchant for prematurely announcing the appearance of important moderate Muslim scholars and hopes for Islamic democracy. He regularly denounced those concerned about terrorism as part of a “terrorism industry.” With exquisite timing, he had an article, “The Future of Islam,” in the Summer 2001 issue of The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, criticizing American intelligence for their concerns about Bin Laden, out on the newsstands on September 11, 2001.

But being exquisitely wrong does no damage to intellectual reputations in America, and Esposito is perhaps the most influential scholar of Islam in the United States. His latest book, What Everybody Needs to Know About Islam, is a primer outlining, for example, the difference between imams, ulamas, and muftis, and on angels, marriage, divorce, and the like. Most of the book is clear, informative, and largely harmless, if rather bland. However, problems arise when Esposito gets into politics. He describes massacres of Christians in Pakistan as “sporadic conflicts between Muslims and Christians,” though with no examples of any religiously motivated murders of Muslims by Christians. On terrorism, he writes that we “must put an end to the spiral of fear, hatred, and violence, spawned by ignorance, that no longer only afflicts other countries but has come home to America.” But “spirals” of violence imply two sides locked in escalating reactive combat. He never says what such spiral America is in. Nor is ignorance relevant. Al-Qaeda activists are often graduate students with extensive knowledge of the West. They are not ignorant: they know it well and hate us.

In the same waffly way, he describes the Salman Rushdie affair as “fueled by a gulf of misunderstanding…between a liberal, secular culture…and a more conservative Muslim community….” He never says what the misunderstanding is. In fact Khomeini well understood that Rushdie was critical of his version of Islam, and we well understood that Khomeini called for the murder of Rushdie and all those like him. We understood each other well: we have very different conceptions of the nature of law and human freedom.

To understand how such errors can be granted credence in the modern academy, it is good to read Martin Kramer’s Ivory Towers on Sand. Kramer documents the capture of the Middle East Studies Association, the main grouping of American academics who deal with Islam, by the post-colonialist theories of Edward Said and other trendy anti-American social science ephemera. The result is apologia for Islamist authoritarians, ill-informed attacks on U.S. policy, and ignorance and incompetence in the face of terrorism.

Noah Feldman’s views are reminiscent of Esposito’s, with whom he has collaborated. This spring, he was sent to Baghdad by the Bush Administration to head Iraq’s constitutional drafting committee. He seemed a new bright young thing: NYU professor raised in an orthodox Jewish home, Rhodes scholar, Oxford doctorate in Islamic studies, Yale law degree. The fact that he was only 32, and had been the chief legal researcher for the Gore campaign in the 2000 Florida recount, didn’t appear to damage him in the eyes of the administration. However, when people got a look at his first book, After Jihad, things hit the fan.

Feldman argues that the U.S. should bring Islamic extremists and jihadists into the electoral process and, if they win elections, so be it; at least they will like us better for it and may not be so anti-American or so willing to use violence in the future. He laments certain brutalities against women and others in Islamist systems but takes a multicultural line that this is what people do in that part of the world. Feldman writes, “Iran now provides some indication of how democracy can tentatively begin to make itself felt in a thoroughly Islamic environment,” which seems OK until you realize that he means this as a positive statement. His definition of democracy begins and ends with elections, with little interest in republican principles and individual rights. After enough people pointed out that this was not really the model that the U.S. wanted to create in Iraq, he was brought home.

Robert Spencer’s Islam Unveiled is critical of Islam and somewhat of an antidote to Esposito’s and Feldman’s rosier views. He argues, amongst other things, that the modern mythology of the Crusades has little to do with present Islamic anger, outlines the widespread repression of minority religions in Muslim lands, and details the widespread murder of “apostates” from Islam. What happened to Salman Rushdie was not at all unusual. In short, he shows that repression and violence in the Muslim world is far more widespread and pervasive than the media and the academy admit.

He seems also to be arguing that violence and repression are intrinsic to Islam, though he occasionally qualifies this, but here his argument is thin. His basic method is to point out injustices committed by Muslims and then counter those who say that such injustices have nothing to do with Islam by demonstrating that the Koran and hadith teach such actions.

He admits that similar teachings on slavery, adultery, the treatment of other religions, and war in the name of God, can also be found in the Bible. But then he notes that, since the Bible is acknowledged by even the most conservative to have been composed by many authors over many centuries in several languages, Christianity and Judaism have had to develop modes of exegesis in which later revelation supercedes the earlier. However, since the Koran is understood by Muslims to have been revealed directly to Muhammad over a few short years, and the hadith cover what only Mohammed said and did, the possibility of any historical interpretive dimension in Islam is much more difficult.

This is true, but difficult is not the same as impossible. Islam has produced great philosophers who engaged Islam with Greek philosophy. The Mu’tazilites, who did this, were a dominant force in the ninth century Abbasid Caliphate. Sufis, who are perhaps the majority of current Muslims, do similar things with mystic and spiritual thought. These currents have always existed in Islam. Implying that they are not really Islamic adopts the same interpretive method as the extremists and undercuts those who could be our allies.

* * *

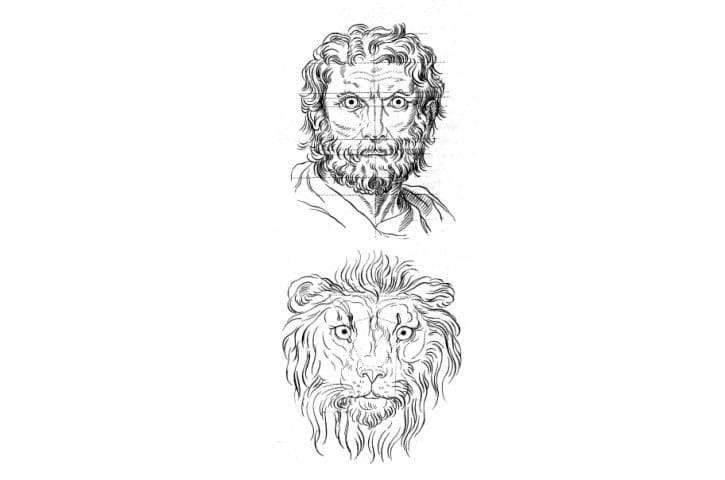

Other books try to distinguish good from bad Islam. Stephen Schwartz’s The Two Faces of Islam takes aim at Saudi Arabia and its fanatical Wahhabi brand of Islam, which he labels a “fascistic” cult. Schwartz, a Muslim and the Director of the Islam and Democracy program at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, details the rise of the Saudi regime and its aggressive promotion of the most reactionary form of Islam throughout the world, including the United States. He also gives a useful outline of Muslim beliefs and of other currents within Islam, especially of Sufism. This otherwise good book is marred by Schwartz’s almost Manichean approach wherein all bad things in the Muslim world are ascribed to the work of the Wahhabis. He seems to imply that there are no other sources of repression in the Islamic world. Hence, he treats the work of the Indian Muslim Mawlana Mawdudi, perhaps the most influential Muslim writer of the 20th century, and the ideological father of many of Pakistan’s, Afghanistan’s, and Central Asia’s Islamists, as basically an offshoot of the Wahhabis. He also takes a too benign view of the current regime in Iran. His An Activist’s Guide to Arab and Muslim Campus and Community Organizations in North America, written under the name Suleyman Ahmad al-Kosovi, is a good guide to Wahhabi influence in the United States, particularly in funding many of the most prominent Muslim public affairs groups such as the Council on American-Islamic Relations, a revealing name, and the American Muslim Council.

The subject of Saudi and Wahhabi influence is also taken up in books by Robert Baer and Dore Gold. Gold is a former Israeli Ambassador to the United Nations, while Baer was a CIA case officer handling agents that infiltrated Hezbollah, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command, Libyan intelligence, Fatah-Hawari, and al-Qaeda. Gold explores links between the current wave of global terrorism, from the World Trade Center to bombings in the Philippines and Indonesia, and an ideology of hatred taught in schools and mosques in the Saudi kingdom. Baer gives a similar picture, of a “kingdom built on thievery, one that nurtures terrorism, destroys any possibility of a middle class based on property rights, and promotes slavery and prostitution.” He also argues that the U.S. has been aware of the problems of the divided Al Sa’ud family for years, but has ignored them in order to keep lucrative business deals afloat, and so has compromised intelligence efforts to combat Islamist terrorism. He raises the possibility of the U.S. seizing the Saudi oil fields and forcing a regime change on its own terms.

* * *

Some very good books have appeared recently. Michael Cook’s The Koran: A Very Short Introduction is a wonderful introduction, covering text, context, history, format, and calligraphy clearly and even wittily. Such an introduction is especially valuable since the Koran is a difficult book, lyrical and poetic, and with chapters ordered simply from the longest to the shortest. It is the centerpiece of revelation in Islam, and pious Muslims believe that it is eternal and uncreated, present in heaven with God before being revealed to Mohammed. One can be punished, even executed, for defacing a page of a Koran, even unwittingly. Since Arabic is understood to be the language of heaven, Islam’s spread also means the spread of Arabic. Many children in madrassas throughout the world understand almost no Arabic but still learn the Koran by heart in that language. In places where radical Islam is growing, such as northern Nigeria, or Aceh in Indonesia, Arabic has been declared an official language, though almost none of the population speaks it. Unlike most Christianity, Islam often explicitly treats the language and culture of the Arabs as normative for Muslims.

Khalid Duran’s Children Of Abraham is a good book for people of any faith. He simply gives a straightforward outline of what Muslims believe and how this compares to Jewish beliefs, and follows this up with a denunciation of Islamist terrorism. For his pains, probably based on his cooperation with the American Jewish Committee rather than the content of the book, Duran was pilloried by the Council on American-Islamic Relations and other members of the Wahhabi lobby in Washington, and had a fatwa calling for his death issued by a Jordanian jurist, Abu Zant.

It is common in the West to think of the Middle East as Muslim and Arab. In fact the region is more religiously diverse than is the United States. Mordechai Nisan’s Minorities in the Middle East is an invaluable introduction to the world of ethnic Kurds, Berbers, Baluchis, of heterodox Muslims, such as the Druze (key in Lebanon) or the Alawites (who run Syria), and of widespread Christian groups such as the Copts in Egypt, Armenians, Assyrians, and Maronites. Many of these groups are rapidly fleeing their ancient homelands and now look hopefully, if skeptically, to the American-led regime in Iraq as a possible step in halting this exodus.

There are many treatments of human rights and Islam, most of them marked by wishful thinking, but only Ann Mayer’sIslam and Human Rights carefully examines the actual guarantees given in Islamic human rights documents. She allows Islamic sources to speak for themselves and reveals the differences between the English and Arabic versions. She shows how the ringing guarantees of human rights given in these documents are always subordinated to a, usually undefined, Islamic law.

* * *

Among the most hopeful signs of serious Muslim intellectual work committed to freedom are the writings of Khaled Abou El-Fadl, who recently moved from UCLA to Yale Law School. He is turning out several books a year but of especial interest is his Reasoning with God, which traces the relation between reason and religion in medieval Islam and afterwards. He focuses especially on the nature of divine will and proposes taking reasoning beyond the traditional Islamic boundaries of textual interpretation. The fact that El Fadl’s work is often isolated reveals how weak is America’s current intellectual engagement with Islam. A thousand years ago the greatest minds of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, such as Thomas Aquinas, Maimonides, Al-Farabi, and Averroes were engaged in fundamental debate about the nature of revelation, of faith, of reason, of law, and in their respectful disagreements created a common discourse across their religious boundaries. In the modern age we are left with vacuous calls to toleration and diversity. Unless American thinking and policy become once more rooted in political philosophy of such depth, we are likely to continue to flail and be rescued only by the excellence of our military.

Other good news is the reissuing by Owl Books of David Fromkin’s A Peace to End All Peace. Fromkin focuses on the period 1914 to 1922, showing how and why the Allies after World War I created the boundaries of the current Middle East from the remnants of the Ottoman empire. Most of America’s military engagement remains on the boundaries of this empire—in Bosnia and Kosovo as well as Lebanon, Iraq, and Kuwait, and their neighbors. As Fromkin wrote in 1989, “The settlement of 1922, therefore, does not belong entirely or even mostly to the past; it is at the very heart of current wars, conflicts and politics in the Middle East, for the questions that Kitchener, Lloyd George, and Churchill opened up are even now being contested by force of arms, year after year, in the ruined streets of Beirut, along the banks of the slow moving Tigris-Euphrates, and by the waters of Biblical Jordan.” Fortunately, this is also history in a grand style, bursting with prodigious personalities, and reads like a novel. Especially for readers of this journal, it may not be amiss to add that the book is structured around the personality of Winston Churchill.

Barry Rubin and Judith Colp Rubin’s Anti-American Terrorism in the Middle East is a valuable reader with selections from and introductions to the major theorists of Islamist terrorism, including Hassan al-Banna, Sayyid Qutb, Khomeini, bin Laden, and sundry Hamas and Hezbollah spokesmen. It shows that their deep-rooted ideology is not grounded in simple objections to recent American foreign policy in the Middle East but is a historically rooted view of the nature of Islam and its fundamental and necessary opposition to the western world’s commitment to individual freedom and constitutional democracy. It is an excellent companion to Bernard Lewis. My only complaint is that I would like a larger and slightly different book, since most Islamist terrorism is not in the Middle East and is not specifically “anti-American,” but claims victims in Nigeria, Sudan, Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Kashmir. Growing Islamist movements are targeting not only Westerners but also all those that they believe stand in the way of their vision of a restored Islam.

* * *

A final piece of good news is that Bernard Lewis is still writing with his customary learning and style. His What Went Wrong?, an expansion of an article in the Atlantic Monthly, is one of the few books written before September 11, 2001, that is key to understanding what brought it about. He traces the precipitous decline of the Islamic world in the last five centuries from the dominant civilization to a poor, weak, and often violent backwater, and shows how much of the Muslim world asks continually, “what went wrong?” Islamism and Islamist terrorism provide the latest of a series of answers, one that says that the problem is that Muslims have forsaken the purity of early Islam and gone whoring after foreign, especially Western, ways. Their solution is an Islamic revival that will institute Islamic law throughout the world and restore the lost Caliphate, and in which violence can and must be used to expel the west (understood as Christendom) and coerce fellow Muslims into the right path. Lewis can both praise and criticize Islam but, as he looks to the future, he sees much to worry about: “If the peoples of the Middle East continue on their present path, the suicide bomber may become a metaphor for the whole region, and there will be no escape from a downward spiral of hate and spite, rage and self-pity, [and] poverty and oppression.”

His The Crisis of Islam, the expansion of another magazine article, this time in the New Yorker, covers similar ground but with a more explicit focus on the roots of Islamist terrorism. Like What Went Wrong? it acknowledges the influence of Western utopian thought and ideology, especially fascism, on modern Islamic movements, and shows how these ideas have become intertwined with pre-existing Islamic motifs to produce a poisonous mixture. This book also ends on a pessimistic note: “If the leaders of [al-Qaeda] can persuade the world of Islam to accept their views and their leadership, then a long and bitter struggle lies ahead, and not only for America…. Sooner or later, [al-Qaeda] and related groups will clash with the other neighbors of Islam—Russia, China, India—who may prove less squeamish than the Americans in using their power against Muslims and their sanctities. If the fundamentalists are correct in their calculations, and succeed in their war, then a dark future awaits the world, especially that part of it that embraces Islam.”

Contemporary Islam will not be reformed quickly or easily, and so America must be prepared at least for several decades to maintain and enhance its military capabilities to combat terrorism and violence in the Muslim world. We also need to avoid the naïve wishful thinking that treats Islamist terrorism as simply rooted in ignorance or poverty or U.S. policy in the Middle East, and realize that it is rooted in a thoughtful and historically aware view of the world. But, while we do this, we need to learn of and to encourage those Muslims to whom a commitment to Islam means a genuine commitment to an open society. I was recently at a gathering of Muslim scholars where one related that, when he was home schooled by his father to know and love Islam and America, “I grew up thinking that one of the greatest Muslims who ever lived was a man named Ibrahim Lincoln.”