Books Reviewed

Jonathan Zittrain’s standing in the legal academic establishment’s cyber division could not be better. He co-founded Harvard Law School’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, where he teaches Entrepreneurial Legal Studies, and he holds the chair in Internet Governance and Regulation at Oxford.

In The Future of the Internet—And How to Stop It, he posits that the internet’s great virtue is its “generativity,” a recent word meaning the “capacity to produce unanticipated change through unfiltered contributions from broad and varied audiences.” Its openness allows free play to the creative genius of users, who push the web in unforeseen directions.

Generativity is good, according to Zittrain, not solely because people like it, but because it enhances “‘semiotic democracy,’ where we can participate in the making and remaking of cultural meanings instead of having them foisted upon us.” He contrasts the creative ferment of the Net with the stodginess of the old-line telephone companies, which centralized intelligence and control and allegedly played dog-in-the-manger by resisting outside innovation while doing little of their own. The beau ideals among the new possibilities opened up by the web are Wikipedia, the open encyclopedia; the free and open source software (FOSS) movement associated with the Linux operating system; and the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI), which uses the otherwise-idle capacity of thousands of P.C.s to analyze data.

But now internet generativity is in danger, Zittrain argues, due to the onslaught of spam, viruses, unstable applications, privacy invasion, copyright issues, and identity theft. The choices made by the internet’s builders to keep the core system simple and to provide maximum user freedom left the system vulnerable to these problems. Responding to them will mean restricting choice. Appliances, instead of serving general purposes like a personal computer, may become “tethered,” designed to perform limited functions under the continuing control of their purveyor. Or administrators might assert control-via the government or private companies-in ways that inhibit generativity.

Most of the book elaborates the threat of control, which is the “future of the internet” forecast in the title. The “how to stop it” advice also promised in the title is pretty light. A section called “Strategies for a Generative Future” urges several protections: hackers should develop workarounds if Internet Service Providers (ISPs) try to exercise control; firms should not be allowed to induce third party contributions with promises of openness, and then renege; and personal information should be shielded from the government even when stored in the computing cloud.

The book concludes that “generosity of spirit is a society’s powerful first line of moderation,” though some unfortunate regulation may become necessary when this fails. Most portentously:

Our fortuitous starting point is a generative device in tens of millions of hands on a neutral Net. To maintain it, the users of those devices must experience the Net as something with which they identify and belong. We must use the generativity of the Net to engage a constituency that will protect and nurture it.

And that’s all there is on how the internet will be stopped from going off the cliff depicted on the book’s cover.

To understand why a volume so thin can be so enthusiastically received (just check out Amazon), one must realize that it is not a stand-alone work. Zittrain is part of a movement of cyber-world legal academics centered at Harvard and Stanford, but with outposts at Berkeley, Duke, Yale, and other major schools. Its creed is drawn from works by, inter alia, Lawrence Lessig of Stanford, who has written a series of books on the open internet and the deleterious impacts of intellectual property; Yochai Benkler of Harvard, who argues that “social production” by peers acting on communitarian rather than market incentives constitutes a new mode of production that will rival capitalism; Tim Wu of Columbia, who says Wikipedia “is best known for popularizing the concept of network neutrality“; and William Fisher of Harvard, who wrote a book on sources of support for intellectual creativity in a world where property rights are both undesirable and unenforceable.

The movement can be characterized by five core sentiments, which include communitarian and democratic idealism, disdain for property rights (especially intellectual property), antipathy toward markets, social libertarianism, and hostility to a group of corporate enemies-among them the content companies (especially the music industry), the telecom carriers (Verizon, AT&T, and Comcast), and Microsoft.

Zittrain’s work is part of this flow of articles, books, conferences, and press releases, and he embodies both the good and bad of it.

* * *

On the plus side, conservatives should find significant aspects of the movement’s thought congenial. The hymns to the generativity of people adapting technology to their particular ends echo Friedrich Hayek or Julian Simon; one could even say there is a belief here in spontaneous order. Conservatives would appreciate the movement’s skepticism about the wisdom of regulators and of large corporate bureaucracies, as well as its reliance on culture and community mores—with law only as a last resort—to encourage good behavior.

The bad takes longer to analyze. The movement has a blind faith that the crowd will provide, but offers little explanation how an internet—or a society—built on its premises would result in high quality physical or intellectual products. One is left wondering how people of such high intelligence reach such flabby conclusions. Several gaps in collective focus are particularly worth noting.

First, there is the movement’s one-sided understanding of economics. No one in its world must make a living, or worry about a return on investment. Large companies don’t help solve problems in organizing human effort; they are malevolent entities. Movement thinkers assume cooperation must be altruistic: if money is involved, it does not count. They are obsessed with the idea that things must be free—not just cheap, or available to anyone willing to pay the price, but free. The towering importance of markets as institutions that facilitate human cooperation is not part of their intellectual or moral arsenal.

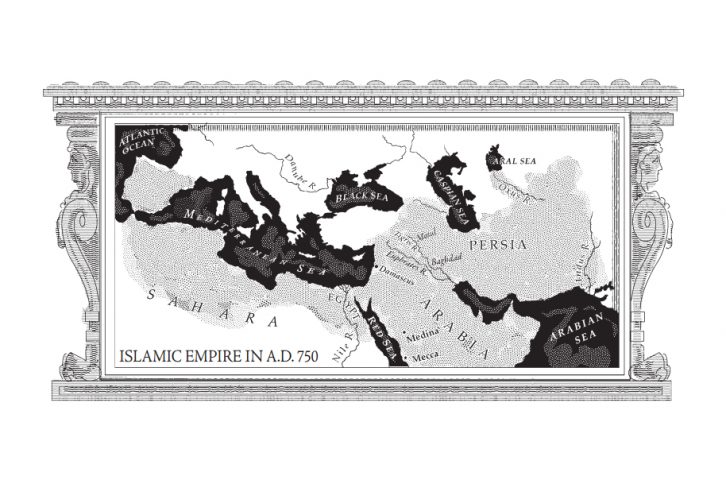

Second, the movement displays an almost complete disregard of history. The internet is treated as a product of immaculate conception. The book has a table that lists various technologies and rates them according to their generativity, but it is trivial. The difference between a knife and a potato peeler is noted, and that between dumbbells and an exercise machine. Missing are the really great examples of generative technology, those that changed societies and civilizations. If one seeks historical parallels to the internet, one should, for starters, think of the sailing ship, the canal, the railroad, and the telegraph—all of which opened the world to new possibilities. The sailing ship, for instance, was like the internet in that the basic medium, the ocean, was open to all. Anyone could build a boat and set sail for his own purposes. It thus differed from the railroads, which required expensive construction, maintenance, and management. But over time even sailing ships needed an immense infrastructure to make the medium work more efficiently, not least because the community norms against piracy didn’t quite do the trick. Navies, self-defense, and hangings were also necessary.

Many of the critical issues in internet governance were foreshadowed by earlier technologies, as has been documented by such thinkers as Andrew Odlyzko. Reading 19th-century legal cases on the meaning of “discriminatory pricing” triggers déjà vu. Indeed, one can go back even earlier, to the common law of common carriers, and examine how our forebears worked their way through rules governing harbors, wharves, inns, ferries, stagecoaches, and canals, with profit to one’s thinking about the internet.

The movement’s historical ignorance extends to intellectual property. Issues of what should be protected, to what degree (if at all), and how to deal with the cumulative nature of knowledge have been dissected repeatedly ever since 1474, when Venice passed the first known patent law.

The movement is disconnected from this tradition. Instead it just repeats its argument that intellectual property protection extends too far and must be cut back. Its theory seems to be that the internet is a new world in which the supply-side incentives that preoccupy the old tradition are irrelevant because the generative spirit will provide all necessary intellectual content. Everything, therefore, must be subordinated to the need for instantaneous availability.

Third, to a large degree, movement scholars reject the idea that individuals need to be able to protect and profit from the fruits of their generativity because they misunderstand the so-called “wisdom of crowds.” A famous example of this wisdom is the county fair contest to judge the weight of an ox. Let enough people participate, and the final total turns out to be remarkably accurate. Ergo, the crowd knows.

But the real lesson is not that that crowd is wise; it is that ignorance is randomly distributed. Thus the guesses of the foolish cancel out, leaving the expert farmers and stock buyers to determine the outcome. The process can be left uncontrolled because as long as ignorance is random, and the number of participants large, there is no need to try to determine in advance who is an expert.

This insight is valuable, but the lesson is not that the crowd is wise, or that everyone is equally generative, or that democracy should rule everything, with the votes of the ignorant and the knowledgeable weighted equally. For example, the internet was indeed crucial to the development of the Linux operating system, but not because it let everyone participate. It allowed geographically dispersed experts to find each other and cooperate, with low transaction costs. Contrary to myth, the actual code writing of Linux has always been a closely-held, murderously meritocratic process. The crowd is allowed to help find bugs, not write the code.

* * *

Free and easy with the fundamentals of economic thought, blind to the illuminations of history, and enamored with the wisdom of crowds (which easily turns into the madness of mobs), the movement floats off into abstractions about net neutrality, universal generativity, communitarian sharing, and semiotic democracy. In the movement’s defense, two factors peculiar to the internet’s explosive growth helped lead these thinkers astray.

As noted, the internet at the beginning was more akin to an ocean with sailing ships than a railroad, because the medium was, like the ocean, simply there. The nature of telephone technology left unused bandwidth that could be used for data transmission. The Defense Department and the National Science Foundation funded the extra gear needed to build the Net on this excess capacity. After it got going, the Net received another rocket boost from the boom of the late 1990s. Many of the companies went bankrupt, but the infrastructure they built did not evaporate. It remains available at a cut rate to this day.

The result was that the telecom companies were not in the position to ration a scarce resource, limiting it to its highest-value uses. They had the bandwidth, at least at the trunk level, and were always trying to lure traffic.

The suddenness with which the internet came into existence also allowed the oddity noted by Zittrain: it took a while for the bad guys to catch up. It always takes a little time; the first train robbery in America did not happen until 1866. Had the build-up gone more slowly, problems of privacy violations, viruses, scams, and spam would have developed in more measured style, and the need for more maintenance and control would have arisen more routinely.

The second special circumstance related to the nature of intellectual property. Generations-worth of material created under old rules and old incentive structures suddenly became available for digitization and distribution. No protections were in place, because intellectual property had always been defended primarily by the cost of reproducing and distributing it. When the marginal cost of these functions fell close to zero, the I.P. was free for the taking. A similar fate even befell new material, such as the news and music. The old business models retained enough vitality to produce content for a time, even as the ravenous Net hollowed out their economic support.

Because the internet was built on excess capacity and free content, the old rules of economics were suspended. Allocating scarce resources was not the issue. With plenty of trunk line dark fiber waiting to be filled, incentives to produce new content could be ignored while the Net python digested the old. The internet encouraged business models that focused on appropriating existing capacity and content, not on producing new content.

The internet is wringing all kinds of transaction costs out of the economic system, including the costs of intellectual collaboration and distributing intellectual products. It is true that this changes the content world in exciting ways, opening up new frontiers for generativity. But it is also true that existing content-producing companies will likely be wiped out, which leaves a little problem of how content will get produced in the future. The suggestion that communitarian production can substitute is absurd. The television show Battlestar Galactica cannot be produced as a free form communitarian enterprise, even if its producers are highly collaborative. If you do not give the creators of BSG both the right and the power to protect their work from random appropriation, how can such shows get made?

Zittrain would apparently favor holding those who pirate BSG individually responsible, one by one. Nothing must be done to lock down the Net, he insists. This too is absurd, given the ubiquity of peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing networks, and the anti-property mindset among the young that has been gleefully fostered by the movement.

The availability of vast amounts of content obscures the problem with the movement’s assumption that unpaid generativity is the future. A service like Wikipedia is derivative. It does not seek original knowledge, and however useful it is (I use it daily—e.g., the 1866 date for the first train robbery), it’s simply the product of running existing books through a scanner or word processor. The contribution to the availability of knowledge is great; the contribution to acquisition of knowledge is small. The oft-made argument that Wikipedia is almost as accurate as the Encyclopedia Britannica is especially droll; considering that the source of much of Wikipedia‘s material is past editions of the Britannica, the online encyclopedia should be as accurate!

* * *

The same can be said for other poster children of communitarian generativity. The core of the FOSS movement is the Linux operating system, which was invented by Unix at Bell Labs. It has been much augmented and improved, but not by battalions of hackers who flip burgers by day to support their night-time addiction to writing code. Linux programmers are paid by IBM, Hewlett-Packard, and their ilk, who see value in commoditizing the operating system so they can get a bigger share of value for their hardware and services.

Even SETI is a dubious example. When it started, excess computing capacity was going to waste. But SETI is not producing any results. Quite a few projects are now competing with it for access to excess P.C. capacity, but, in the absence of a market, it is impossible to judge the best use of resources or provide incentives to shift use.

But the free rides are coming to an end. The old business models that produced important content, notably the news and music businesses, are broken. Without property protection, it is hard to see where new models will come from to encourage professional production. The movement assumes that advertising can pay the bill, but there is no reason to think that the business of selling eyeballs to hucksters can fill the financial gap left by the collapse of real businesses that sold content directly to consumers.

Nor is it likely that today’s glut of unused bandwidth will last. People will think of new uses and demand more and more from the internet. Some of this will come from those old standbys of technical progress—entertainment and pornography—but important business and medical services will also have a role. As the internet becomes more sophisticated so too will the bad guys, as Zittrain says, which makes an increase in centralized control inevitable. The real challenge is building and adapting institutions to limit and rationalize the controllers.

But Zittrain and the movement have little or nothing to say about this challenge, which is unfortunate, since historical experience tends to support their basic policy prejudices. Smart societies, for example, do not allow the controllers of infrastructure to expand control into the generative activities that rely on that infrastructure. A railroad does not get to raise the freight rates charged factories to levels that would capture their entire profit. But neither do factories get to decide the freight rates, since they would opt for zero. And if the question is tossed to the government, then it is settled mostly by political pressure, which is not a good way to make decisions on long term capital investment.

Designing a technical, economic, and legal regime that provides the revenue necessary to support the appropriate amount of infrastructure-and that determines the “appropriate amount”—will not be easy; and unfortunately, the movement’s abstract dedication to “net neutrality” will not be much help.