Books Reviewed

This fall, celebrity intellectual Ta-Nehisi Coates moved on from demanding reparations for America’s racial sins to comparing Israel with the Jim Crow South. “I don’t think I ever, in my life, felt the glare of racism burn stronger and more intense than in Israel,” Coates writes in his new book, The Message. Sloppy and incendiary though this comparison may be, it perfectly captures the logic of today’s radicals, who have translated their hatred of America into hatred of Western nations the world over, and Israel in particular. This new, fashionable antisemitism is not just a passing fancy. It is the fruit of a pathological self-hatred on the part of Europeans, Americans, and Commonwealth citizens who position the Jewish state as a beleaguered representative of Western civilization.

Americans outside the activist-haunted groves of academe were surprised and dismayed in the summer of 2020 to realize the sheer ubiquity of the new racialism, whose adherents vehemently disdain “whiteness” and cast “persons of color” as permanent victims. In the woke cosmology, the world is ruled by what Karl Marx called “alien powers”—sinister forces that are as cruel as they are irredeemable. Of course, some version of this credo had been institutionalized in the academic and intellectual worlds for a very long time, both at the administrative level and throughout educational curricula. But only in 2020 did the general public learn that education has consequences, as indoctrinated students became political fanatics.

***

In the fall of 2023, the other shoe dropped. Decent Americans were shocked again after October 7, when Hamas terrorists cruelly murdered 1,200 people and then took away 251 hostages to the underground tunnels of Gaza. There followed an upheaval that Adam Kirsch, literary critic and features editor at The Wall Street Journal, characterizes as “a seismic change in the way young people in the United States think about Israel and Palestine.” In his thoughtful new book On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice, Kirsch examines the extent and the causes of this change. Polling data from the months after October 7 show that most Americans (at least 80%) supported Israel against Hamas. But in the 18-24 age group, the split was 50-50. No less than 60% of the young agreed that Hamas’s barbaric deeds (including the decapitation of innocents) “can be justified by the grievances of the Palestinians.” The radicalism of the academy had again borne poisonous fruit.

Activist intellectuals, some of them influential and well placed, expressed “excitement and enthusiasm” over Hamas’s assault against the “settler colonial Zionist entity.” Yale professor Zareena Grewal proclaimed on X that “Israel is a murderous, genocidal settler state and Palestinians have every right to resist through armed struggle.” Kirsch documents many equally unhinged sentiments which emanated “from Ivy League campuses, the Democratic Socialists of America, and Black Lives Matter,” as well as from the broader ranks of “progressives” across the country.

The rhetoric became still more grotesque after what Kirsch calls “Israel’s retaliatory invasion of Gaza,” with its “highly disproportionate casualties.” One should add that Hamas did everything in its power to maximize those casualties for propaganda purposes, deliberately situating weaponry and military command centers amid schools, hospitals, and crowded population centers. This heinous tactic was mostly excused by the mainstream press, which helped shape global public opinion. Doctored casualty figures from Gaza’s Ministry of Health (little more than a public relations team for Hamas) identified all Palestinian casualties as civilian casualties. This was uncritically taken as gospel by media outlets and governments across the Western world.

***

Jew-baiting and Jew hatred have thus become de rigueur in activist circles and on social media, especially among the young. Kirsch demonstrates that progressive disdain for Israel flows straight from a deep well of antipathy toward “settler colonialism,” on which basis ideologues deny the moral legitimacy of entire countries. Chief among these are the United States, Australia, Canada, and finally, Israel. Never overwrought, Kirsch calmly notes that these angry moralists are silent about China’s present-day atrocities against the people of Tibet and Xinjiang. Nor do they say a word about the quest for a global political and religious imperium that has marked Islam since its origins in the 7th century A.D. The West, and the West alone, is the target of condemnation.

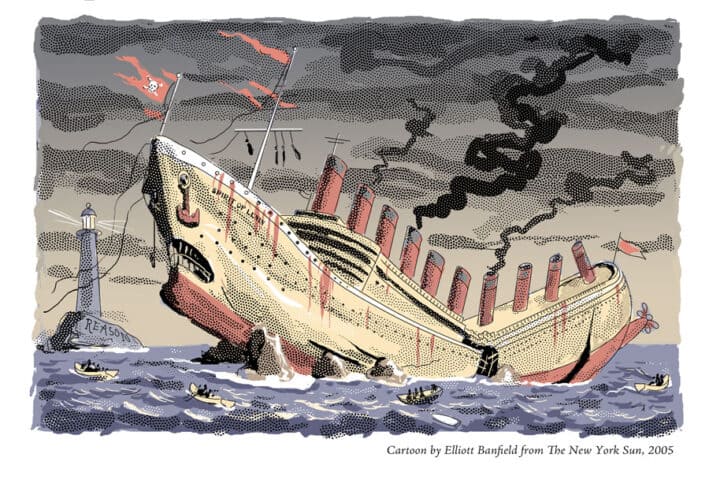

In this framework, colonialism is understood as a permanent “structure” and not a passing historical era. It is said to explain all the evils in the modern world, from the degradation of the environment to “gender” oppression, racism, and rapacious capitalism. It follows that to abolish the scourge of settler colonialism would be to redeem the human condition in one fell swoop. We have here a utopian secular religion arising from a long history of Manichean fanaticism stretching back to the Communists and the Jacobins. Like its predecessors, anti-colonialism “attributes many different varieties of injustice to the same abstraction and promises that slaying this dragon will end them all.” By crudely dividing “the world into the guilty and the innocent,” participants in this crusade ignore the signal fact that all historical actors have complex motives, and none of them embodies good or evil in toto. Ideological Manicheans of all stripes ignore the complexity of human politics, justifying tyrannical coercion and violence against those whom they arbitrarily judge beyond redemption. Near the beginning of this short but rich book, Kirsch gives a succinct assessment of the issue: “These ways of thinking have traditionally produced disastrous results, and the ideology of settler colonialism is already leading idealistic, educated young people down a similar path.”

***

Kirsch makes his point soberly. He clearly aims to persuade moderates and old-fashioned liberals who have not yet faced up to the seriousness of this revolutionary project. To begin with, he points out that “anti-colonialism,” as practiced by rioters and supporters of Hamas, entails a fundamental redefinition of what is meant by “colonialism.” Countries such as Australia and the United States are presumed to belong by permanent right to aboriginal and indigenous populations, whose history the ideologues romanticize beyond recognition. Seen in this light, of course, immigrants who come to the United States today would be no less “settlers” than those who settled the original American colonies before 1776, a point made explicitly by settler colonial theorists and activists. Nor do anti-colonialists give much thought to where “indigenous” people came from before Europeans arrived, or to what cruelties and misdeeds were committed against other tribes and peoples to establish the ostensibly inviolate status of the “original” settlers.

Previous critics of colonialism or imperialism were far more rigorous and principled. In her seminal work, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), Hannah Arendt criticized colonists for their real misdeeds. Even if she was at times unduly harsh or one-sided, Arendt was nonetheless a realist about power politics and acknowledged that the European empires’ “horrors were still marked by a certain moderation.” Unlike the anthropologists, social scientists, and activists who created the pseudo-discipline of “settler colonialism studies” (also known as “post-colonialism”), Arendt did not equate Nazi genocide or Fascist authoritarianism with European conquest. Nor did she loathe Western civilization or attack the Western classics as blueprints for exploitation and domination. She no doubt would have been appalled by those who absurdly call the present-day United States “Turtle Island” after an Iroquois creation myth formalized and embellished by later (non-indigenous) scholars.

Kirsch compellingly shows that the narratives put forward to justify current anti-colonialist dogma have little or nothing to do with history, native or otherwise. Rather, these narratives reflect what one Australian anthropologist called “a growing crisis in white identity,” precipitated in no small part by blood-guilt arguments like those advanced by French Marxist Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth (1961). This crisis has prompted compulsive self-loathing and ludicrous historical revisionism. Free and accomplished societies such as the United States and Australia are redefined as “genocidal” perpetrators of “unbroken” invasion against pristinely moral indigenous societies. As Kirsch points out, this approach is not even genuinely “progressive,” since it implies that “the past was better than the future” and offers no practical hope for reform. Those who inhabit an intellectual “Turtle Island” of their own creation offer no constructive paths forward for the societies they so vociferously condemn or for the native peoples whose largely invented pasts they claim to cherish and esteem.

On this subject Kirsch cites the historian Gerald Horne, who claims that America was born in the 17th century as a “‘hydra-headed monster’ of ‘white supremacy and capitalism,’” which later sprouted an additional “head” in the form of “‘heteropatriarchy.’” The bizarre language of this cult can be heard everywhere from classrooms, to social media, to the pro-Hamas encampments on elite college quads. Since anti-colonial mythology will remain an obstacle to prudent moral and political judgment in our time, it would be a mistake to dismiss its contemporary prominence as a passing phase or to understate the threat it poses to free and decent societies.

***

The great 19th-century American historian George Bancroft (author of the once-hugely famous History of the United States) saw admirable grandeur and daring as well as fearsome violence in the European expeditions to North America. But the theorists of settler colonialism see only criminal rapacity and self-conscious designs for genocide. They are so committed to their partisan allegiances that they judge metaphorical European “crimes” more severely than real indigenous ones. For example, in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (2014), ethnic studies professor Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz gives an account of the Pequot War of 1636-38 that simply ignores Indian murders, violence, and raids on Puritan settlers. These gave rise to escalating retaliations in which, eventually, settlers burned a Pequot village at Mystic and killed 400 people. The fact that semi-nomadic Indian tribes regularly attacked Puritan settlements is an essential part of this mutual tragedy. But activist scholars utterly ignore this crucial part of the story.

As Kirsch wryly points out, those who redefine America as “Turtle Island” accuse settlers of “erasing” indigenous folkways. But they are themselves determined to “erase” the cultural achievements of their enemies. This enables them to create what the political philosopher Eric Voegelin called a “Second Reality,” a fictive “surreality” common to all utopian political religions. The absurdities of this second reality often impose themselves on actual reality. Environmentalist radicals, for instance, use sacrosanct native burial grounds to justify holding up economic development and scientific initiatives that might help impoverished Native Americans as well as the majority population. Many anti-colonialists even deride the “objectivity” of Western science in favor of tribal mysticism, preferring to consign people of all races to primitive superstition than to suffer the indignity of receiving scientific instruction from the hated settler. The works of “white” oppression, even the most estimable and necessary, are held in thoughtless contempt by the acolytes of this new faith.

***

The result is an unintentionally hilarious farce. More and more universities, public organizations, and foundations go out of their way to announce at their events that they are situated—illegally and immorally—on indigenous land. But, of course, none of these institutions have any intention of giving up their little pieces of “Turtle Island.” Kirsch observes that in real political struggles, like those waged by the Viet Minh in Vietnam after 1945 and by the National Liberation Front (FLN) in Algeria after 1954, contestation over land and territory has life-and-death stakes. By contrast, the posturing of woke foundations, museums, and universities amounts to “a rhetorical competition among ‘settlers’ themselves, in which the confession of sin earns moral prestige.” These penitents ostentatiously declare themselves “settler-thieves” in the desperate hope of escaping the consequences that would attach to real guilt. One can find comparable rituals among “anti-racists” hoping to free themselves from the stain of “white privilege.”

Of course, expanding the theory of settlers and oppressed across the whole world renders both categories utterly meaningless. Kirsch points out that it might make sense to apply the term “settler colonial” to certain select groups, such as intransigent white minorities in South Africa or Rhodesia. I would add the qualification, however, that many Dutch Boers born in Africa—much like the million or so native French Algerians—had as much moral and political right to the land of their birth as the Bantus did. But to tar as villians the Americans, Canadians, Australians, and yes, Israelis—who have built free, decent, and vibrant societies in their respective countries—is beyond absurdity. Kirsch points out that to condemn entire populations in this way is “to turn indignation at past injustices into a source of new injustice today.” He concludes, quite reasonably, that the ideologues who “preach vengeance and murder from an ivory tower” should be “rebuked for their inhumanity.”

***

In the final part of the book, Kirsch demonstrates that the settler colonialist template is utterly unfit for the “small and endangered” country of Israel. Genocidal chants of “From the river to the sea” give the game away. There can be no innocuous reading of this demand to eliminate the Jewish state and the Jewish people, whatever angry students and activists may insist. Campus radicals blocking foot traffic in their quads, Ph.D. candidates flaunting keffiyeh scarfs, and militant gay activists lauding Hamas’s terror state (where they would not be tolerated for five minutes) exemplify the tragicomedy of an “anti-genocidal” movement that is willing to tolerate genocide in theory and practice. Young people have been sold on a cult of self-loathing that has now turned on the Jewish people and the Jewish state as an avatar of the hateful West.

In the face of this ideological onslaught, Kirsch patiently explains why Israel cannot be “decolonized” without rivers of blood and massive new injustices. He also enumerates the multiple reasons why the Jewish people have an equally just claim to “indigeneity” in the Holy Land. Zionist settlers in the Yishuv, the pre-1948 Jewish settlement, did not exploit Palestinian labor in anything resembling an oppressive way. Tellingly, the Palestinian population has risen dramatically since the establishment of the Israeli state—hardly evidence of genocide.

Kirsch could have strengthened his case by emphasizing how the Jews of the Yishuv made the desert bloom—how they rebuilt Jerusalem as a vibrant and energetic city and drew more Arabs to the region. (It is worthwhile to remember that the longtime Palestinian Liberation Organization leader and master terrorist Yasser Arafat was born in Egypt, not Israel.) Kirsch does not belittle the just claims of Palestinians; he hopes for a “two-state solution” when and if it becomes possible. But he points out that Palestine’s self-appointed leaders have never been open to such a solution, which was first offered to them by the United Nations in 1947. Perhaps they never will be. Their single-minded aim is to drive the Jews into the sea.

***

Whereas Kirsch provides a measured, sustained, but ultimately devastating critique of the post-colonialist narrative, self-described political “centrist” Jeff Flynn-Paul sets the record straight with a lively and accessible retelling of colonial history as it really was. An American-born historian who teaches at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, Flynn-Paul has written widely on war and the modern state, as well as the economics of global slavery. His book Not Stolen: The Truth About European Colonialism in the New World began as a lively and widely discussed essay in The Spectator of London. Flynn-Paul does not mount “a defense of white innocence,” as an egregious hit-job by Thomas Lecaque, “How Bad History Feeds Far-Right Fantasies,” at the website of Foreign Policy magazine suggested, but instead sees “saints and sinners,” and everything in between, on all sides of the colonial equation. He shows in lucid prose that the Spanish, led by Queen Isabella and a series of popes, opposed the enslavement of New World Indians. Intermarriage and intermingling between Spanish colonists and Amero-Indians was the norm, as the present-day demography of the Americas south of the Rio Grande ought to make clear. Contrary to legend, much of the land appropriated by European settlers was bought legally and not stolen at gunpoint.

White settlers were guilty of their share of crimes and massacres. But this was generally the exception, not the rule. Native warriors were brave and fierce, but they also sadistically tortured, killed, and burned prisoners (white as well as Indian) without reservation. Their tribes fought viciously against each other and had no sense of sharing a common “Indian” identity. Only those who became Christian had any notion even of a common humanity. Flynn-Paul shows further that the “nomadic and semi-nomadic” Indian tribes were hardly “natural communists,” as many claim today. Nor were they the peaceful environmentalists portrayed in the 1990 movie Dances with Wolves. As Alexis de Tocqueville showed in Volume I of Democracy in America, there was a natural grandeur inherent in the proud warrior spirit of the native peoples. But it was, lamentably, compatible with ignorance and cruelty.

***

Tocqueville witnessed and movingly condemned the Trail of Tears, the heinous forced evacuation of the Cherokees and other native peoples (60,000 people in all) from their own self-governing communities in Georgia, Alabama, and other territories starting in 1830. But as Flynn-Paul points out, some prominent American politicians and public voices also vehemently denounced this crime, and some members of Congress even left the country in protest. Before them, George Washington also advocated a policy of magnanimity toward native peoples.

Turning to the present day, Flynn-Paul denounces the grossly hyperbolic talk of “cultural genocide” which associates religious evangelization and cultural assimilation with genocide per se. Just a few years ago, in Canada, this way of thinking culminated in hysteria about natives allegedly buried in unmarked graves at a Catholic Indian residential school in the province of British Columbia. Untold numbers of churches were burned in retaliation (a terror campaign which Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called “understandable”) before it was discovered that no graves existed at the site. So Flynn-Paul’s call for a “balanced history of European colonization” in the New World could not be more timely and urgent. He ends his book with a warning that the “‘stolen ground’ chorus,” and the “genocide” agitprop that accompanies it, may paradoxically “enable modern-day genocide and human rights abuses on a far greater scale” by denying the moral legitimacy, and undermining the self-respect, of imperfect but free and decent democracies.

Adam Kirsch and Jeff Flynn-Paul help point the way to recovering balanced historical analysis, which is not only an academic matter. Informed, self-respecting, but self-critical moral reasoning is indispensable for citizens of any free nation. The issues these authors address so well are too important to be left to fanatical clerics in the cult of Western self-loathing.