Possibly someone will surprise us at the last minute. Possibly the coronavirus is to blame. But with 2020 nearly over, it looks like the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival at Plymouth, Massachusetts, is going to pass uncommemorated. There have been no TV features relating what happened 400 years ago. No magazine essays unstitching the religious conflicts that drove the Puritans into exile or the republican philosophy of the Mayflower Compact and its relevance to us. Absent is the passion society’s leaders bring to commemorations they actually care about—the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, the centennial of World War I, and all those local triumphs of the Civil Rights movement that have come to fill our civic calendar like so many saints’ days. Half a generation ago, journalist and historian Éric Zemmour expressed astonishment that the French government was ignoring the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Austerlitz (1805). What hope is there, he asked, for a nation that doesn’t care about the greatest military victory of its greatest leader, in this case Napoleon? It was a good question. Here is a better one: what hope is there for a nation that doesn’t care about its beginnings?

At work is more than a failure to summon the Pilgrims to mind. There is an active project to exorcise them, in order that the country might find itself a past more congruent with its present-day political commitments. A year ago, the New York Times launched a “1619 Project” dedicated to the proposition that the original, the more consequential, and therefore the real founding of the country came with the arrival of a Portuguese slave ship in Jamestown the year before the Pilgrims arrived.

Those locals to whom the Pilgrims’ memory has been entrusted have rushed to cooperate in their demotion. In July, citing the “reckoning with racial injustice” underway in street protests across the country, the trustees of Plimoth Plantation, the living-history museum that has explained the Pilgrim settlement to schoolchildren and tourists since 1947, announced they were changing the institution’s name to Plimoth Patuxet (the Wampanoag name for the spot) in order to be more inclusive. The director of the Provincetown Museum boasted to the Boston Globe about the “tough conversations” he had had as he trained his staff to think about the Mayflower landing in a different way. The Pilgrims survived, he said, because the Wampanoag Indians “helped them in true social-justice fashion.” A founder of the Bernie Sanders-linked group Indivisible Plymouth complained over the summer about such local commemorations as were planned: “[S]houldn’t the struggle for the right for women to vote,” she asked, “be as well-known as the story of the Mayflower and 1620?”

To which one can only reply: Isn’t it already? Even in Plymouth?

As in every matter that involves ethnic, cultural, or racial interactions, the “traditional” or “establishment” narrative has been censored in schools, city halls, and all the traditional places it was once told. No establishment lifts a finger to defend it. The “subversive” or “alternative” narrative, meanwhile, has become doctrine: it is championed by corporations and foundations and backed by the government’s full power to punish.

Over time, the intended result is reached: authorities cannot teach the story of the Pilgrims even if they would, because most of them no longer know it. The story of the settlement of North America has become a scandal. It is worth looking more closely at who the Pilgrims were, and what they did, to understand why so many people have grown so uncomfortable telling their story.

The Pilgrim Settlement

It is still told in straightforward histories, of which a representative recent example is Nathaniel Philbrick’s Mayflower (2006). The Pilgrims were “Separatists” from the Church of England. Like the Massachusetts Bay Puritans who later in the decade would settle just north of them in Boston, the Pilgrims believed the Church of England had been corrupted by venality and anti-scriptural superstitions inherited from Catholicism. Unlike the Puritans, though, the Pilgrims broke communion with the English church, and faced persecution for it. They lived in exile in Leiden for a decade, in the same neighborhood where the young Rembrandt was then attending school, and then made a (bad) bargain with a band of investors called the Merchant Adventurers. In exchange for the authorization to set up a colony in North America, the Pilgrims would send furs, salt fish, and other profitable commodities to the Adventurers sitting back in London. (Like today’s “venture” capitalists, the Adventurers arrogated to themselves a dashing job-description that more properly belonged to those they were financing.) Just over a hundred people landed at Plymouth on December 22, 1620, most of them Pilgrims, though some were godless sailors, craftsmen, and other “strangers.” To minimize strife, the men had signed a Mayflower Compact before stepping on shore, pledging to honor individually the laws they made collectively. About 35 million Americans are descended from them.

Alone, freezing, poorly provisioned, half the Pilgrims died of starvation and disease that first winter. One day, Samoset, a chief of the Abenaki Indians in what is now Maine, walked into Plymouth and addressed the settlers in English. He introduced the Pilgrims to Massasoit, chief of the region’s Wampanoag Indians, and to Squanto, a second English-speaker. Massasoit, who lived just west of the Pilgrims in the settlement of Pokanoket, offered food. Squanto offered planting and fishing advice. Most important, the two sides agreed to a common defense pact. In the autumn of 1621, the Pilgrims and the Pokanoket Wampanoags shared a giant feast, the first “Thanksgiving.”

That they were grateful is not surprising. Against the backdrop of the early 17th century, the Pilgrims’ bond with the Wampanoags was atypical to the point of being mystifying. People had wanted to settle New England for a long time. The Virginia explorer John Smith, who first mapped the region for the British crown, thought Massachusetts a paradise. Hundreds of cod-fishing boats were working the Maine coast yearly by the time the Pilgrims arrived. But encounters between Indians and Europeans, as when fishermen landed to trade, most often ended in violence. Two years after the Pilgrims landed, Powhatan Indians slaughtered 347 colonists in Jamestown. All over the new world there had been stories like this, at least since 1528, when Giovanni da Verrazzano (the first great explorer of what is now the northeastern United States), having rowed ashore from his moored boat to explore a Caribbean island he assumed uninhabited, was captured and eaten on the beach in front of his horrified crew.

The Englishmen who explored Massachusetts Bay did nothing to make themselves especially welcome. In the decade before the Pilgrims arrived, there had been various incidents in which natives, dozens in total, had been invited on board French, English, Dutch, or Spanish ships and kidnapped, either to be trained as guides or sold as slaves. One of these was Squanto, captured near Plymouth in 1614, who escaped from the Spanish slave port of Málaga to London and made his way back to his native Plymouth. The Pilgrims, naïve about this history, blundered into a war zone. They themselves stole buried corn in their first hungry days in the New World, and were greeted with a shower of arrows on their first encounter with Indians. They did plenty of fighting, led by a secular mercenary named Myles Standish—brave, erudite, underhanded, and so diminutive that he was known (though not to his face) as “Captain Shrimp.” But even decades later, as tension rose between nearby colonies and nearby Indians, the Pilgrim-Wampanoag peace held.

What made the Wampanoag different? It is not that they were a particularly affable bunch of Indians. Pilgrim governor William Bradford cited a letter sent him just before the Pilgrims sailed: “The Pocanockets, which live to the west of Plymouth, bear an inveterate malice to the English, and are of more strength than all the savages from thence to Penobscot.” That letter came from an English explorer “Mr. Dermer.” By the time the Pilgrims sailed he had already been mortally wounded by Wampanoag warriors on a trade visit he had made to Martha’s Vineyard, accompanied by Squanto as translator. Those warriors had been led by the shrewd Epenow, another kidnapped Wampanoag who had learned English in captivity and escaped on a return voyage for which he was supposed to work enlisted as a guide.

But just before the Pilgrims’ arrival the Wampanoags, although warlike, suddenly found themselves weakened to the point of mortal danger. The central fact of 17th-century American history is biological, not political or military. It is the lack of any resistance among Indians, first, to European diseases (such as smallpox and typhus) and, later, to African ones (such as malaria and yellow fever). Some Indian settlements were completely depopulated.

One of these was Patuxet, Squanto’s home, on the spot that settlers would call Plymouth. The French adventurer Samuel de Champlain, having anchored there in 1605, left a woodcut of teeming populations tending abundant fields. But when Squanto made what he surely thought would be a triumphal return in 1619, he found the place abandoned. So did the Pilgrims when they landed a year later.

The desolation would have had a profound psychological effect. The Pilgrims would have believed themselves favored by Providence. The Indians, seeing their neighbors drop like flies and the colonists escape unharmed, would have assumed the God the settlers proclaimed was a mighty one. But psychology was not the whole of it. As the historian Herbert Milton Sylvester wrote in his thrilling three-volume Indian Wars of New England (1910): “Had the plague not occurred as it did, the English would have been driven into the sea.”

The Wampanoags never recovered their demographic position, and the rapid influx of colonial settlers began to confine the Indians to their towns. After Massasoit’s death in 1660, the peace between Pilgrims and Wampanoags would break down.

Revering Our Forebears

Many peoples settled the United States. Why, among them, should the Pilgrims have so long occupied the central place? What about this story was so especially inspiring or symbolic? The rapid rise of the United States—transformed in less than two centuries from a wilderness into a vast independent republic, on a par, both commercially and culturally, with many European countries—made this an important question, not just for America’s pride but for the world’s edification.

John Quincy Adams, a young Massachusetts state senator and son of the recently ousted president, spoke at a commemoration in Plymouth in 1802. The simplest reason we remembered the Pilgrims, he made clear, is that they were founders. It is legitimate to ask, as the authors of the 1619 Project do in our own time, whether there were other participants in that founding worthy of posterity’s notice. Unlike these later critics, however, Adams made no invidious or exclusive claim to the preeminence of his own subculture. “Our affections as citizens embrace the whole extent of the Union,” he said, “and the names of Raleigh, Smith, Winthrop, Calvert, Penn, and Oglethorpe excite in our minds recollections equally pleasing and gratitude equally fervent with those of Carver and Bradford.”

Adams nonetheless observed a few ways in which the story of Plymouth highlighted exceptional aspects of America’s national life. In tracing their origins, “other nations have generally been compelled to plunge into the chaos of impenetrable antiquity, or to trace a lawless ancestry into the caverns of ravishers and robbers.” Not so the Pilgrims. The only thing uncultivated about them was the landscape. The settlers of Plymouth were already embedded in a high European civilization.

And a specific one. The Pilgrims were Englishmen—even English patriots, Adams asserted. Paradoxically, their 3,000-mile journey out of Dutch exile was intended to bring them closer to England. “That country which had ejected you so cruelly from her bosom,” Adams said, “you still delighted to contemplate in the character of an affectionate and beloved mother.”

What was unique about the Pilgrims, even among other English settlers of their time, is that they came for love of God, not love of money. From Columbus’s voyages until the settlement of Virginia, explorers and exploiters had taken great risks—but always for their own enrichment (and at one remove, a monarch’s glory). “It was reserved for the first settlers of new England,” said Adams, “to perform achievements equally arduous, to trample down obstructions equally formidable, to dispel dangers equally terrific, under the single inspiration of conscience.”

You need not share their religion to honor the humble Pilgrims. But there is no getting around that what they did was human, and complicated. The Pilgrims were seeking one thing: the freedom to establish a theocracy. This “single inspiration,” as Adams called it, turned out to be double. They got their freedom, because they were willing to struggle for it. But they did not get their theocracy, because it was incompatible with their freedom.

In making the case for the Pilgrim Fathers, Adams ignores their theology and asks us to notice instead three things that involve their political behavior. First, they wrote the Mayflower Compact, which showed that “the nature of civil government, abstracted from the political institutions of their native country, had been an object of their serious meditation.” Second, they proved capable of reforming those institutions at the very outset, having abandoned a utopian experiment in common holdings to revert to private property. And third, they had treated the natives with decency and respect.

Adams clearly understands that this last argument is an awkward one, because the natives had been wiped out since they encountered the English. He rightly does not blame Europeans or Africans for carrying the diseases that enervated the Indians (nor would he have fully understood the science of what happened), but takes as his starting point the desolation the Pilgrims found on their arrival: “Is New England supposed to be held by a few tens of thousands in perpetuity? Shall the fields and the valleys, which a beneficent God has formed to teem with the life of innumerable multitudes, be condemned to everlasting barrenness?” It is a sensible argument, but it will sound to 21st-century ears like an economic answer to a moral question.

Eighteen years later, in 1820, Federalist lawyer and future senator Daniel Webster also spoke at Plymouth. No friend of John Quincy Adams, he nonetheless laid a similar stress on, first, the Pilgrims’ introduction of “civilization and an English race into New England” and, second, the “peculiar original character of the New England Colonies” in worship rather than avarice. New England was not like those “Asiatic establishments” and West Indian plantations where “the owners of the soil and of the capital seldom consider themselves at home in the colony,” traffic in luxuries rather than necessities, and exploit slave labor. (Webster was not more anti-slavery than Adams—no one was—but one can hear a note of abolitionist sectional hostility creeping in that was absent from Adams’s address.)

This is the old, “patriotic” understanding of what the Pilgrims were about. It is not necessarily a reactionary understanding. Over time, particularly after Plymouth was absorbed into the larger, more dynamic Massachusetts Bay Colony at the end of the 17th century, Puritanism would change, evolving into Unitarianism and generating various seemingly distant political enthusiasms, from abolitionism to Prohibitionism to women’s suffrage. Herbert Milton Sylvester wrote that “[t]he liberalism of the present century is a regenerated Puritanism,” and so are many ideologies that would understand themselves as dissents from Puritanism, right down to the superstitions of political correctness today.

As Webster spoke in Plymouth about the English settlers, Washington Irving was living in England and studying the Pilgrims’ sons—particularly their bloody suppression of the great Wampanoag uprising of the 1670s. Where Webster dismissed the subject of the Indian wars in half a sentence, Irving was appalled. “Posterity,” he wrote, “will either turn with horror and incredulity from the tale, or blush with indignation at the inhumanity of their forefathers.”

Deadliest War

If Plymouth’s reputation is on the wane in our time, it is at least partly because historians now treat King Philip’s War (1675–76) not as a separate episode but as part of the story of the Pilgrim founding—the sanguinary final stage of it. Roughly a tenth of the European adult males of the southern New England colonies were killed or captured in the conflict, and half their villages burnt. Indians had it worse: “The settlers first despoiled the savages of their fishing-grounds, their hunting- and corn-lands,” writes the unmatchable Sylvester, “and then they annihilated them with fire and sword because they resented these aggressions.” It was, per capita, the deadliest war in American history.

The story had the shape of a Shakespearean tragedy. The gentle Massasoit’s son Metacom (known as Philip) led part of the Wampanoags and a confederation of central New England tribes against the Plymouth settlers he had grown up among. Those settlers, fortified by other New England colonies and several Indian tribes, were led, at least at first, by William Bradford, the son of the late governor.

The end to half-a-century of Wampanoag-English peace was less sudden than it looked. The logic of King Philip’s War was already evident in a war the Massachusetts Bay Colony had launched in 1636 against the Pequots of the southern Connecticut River Valley. Although Plymouth and its Wampanoag allies both took the side of the Massachusetts Bay settlers, Governor Bradford was troubled even then by rumblings he heard of a new, pan-Indian alliance. The Pequots were calling for the long-divided tribes to forget their ancient differences and focus their enmity on the usurping English. Bradford writes that the Pequots

sought to make peace with the Narragansetts, and used very pernicious arguments to move them thereunto: as that the English were strangers and began to overspread their country, and would deprive them thereof in time, if they were suffered to grow and increase. And if the Narragansetts did assist the English to subdue them [the Pequots], they did but make way for their own overthrow, for if they were rooted out, the English would soon take occasion to subjugate them [the Narragansetts].

This judgment would prove correct in all its particulars.

There was something in the Indians’ culture of warfare that struck the European sensibility as especially sadistic. They were fond of ruses and ambushes, scalped their adversaries, tortured and enslaved their captives, and taunted the survivors. Sylvester writes:

They had roasted Butterfield at the stake, as well as Tilly. They had slain men and women at Wethersfield; they had carried their children away into captivity; and much of this had been a matter of visual experience…. It is no wonder that the cup of vengeance, once at the white man’s lips, should be drained to the very dregs.

A low point came with the battle of Fort Mystic. English troops surrounded the fort, then occupied by perhaps 500 women and children, breached its walls, and lit the wigwams on fire. They killed the men as they emerged from the inferno, and captured the women and children to sell into slavery.

Such episodes left an impression even on the Indian allies of the English, and a few years later, a beloved Narragansett chieftain named Miantonomo began traveling around with a message for leaders of the southern New England tribes: “Brothers, we must be one as the English are, or we shall soon all be destroyed.”

Though Miantonomo was betrayed and executed, distrust of the English and sentiments of pan-Indian solidarity had reached the Wampanoags, and eventually would reach King Philip.

Descending into Violence

A generation later, in the 1670s, Massasoit’s son and successor Metacom (also called Philip) began to behave erratically, selling off large and vitally important parcels of tribal land. Indians were already hemmed in by the encroachment of settlers, who had come to outnumber the Indians two to one. That the sold lands often passed to neighboring Rhode Island infuriated the Plymouth colonists.

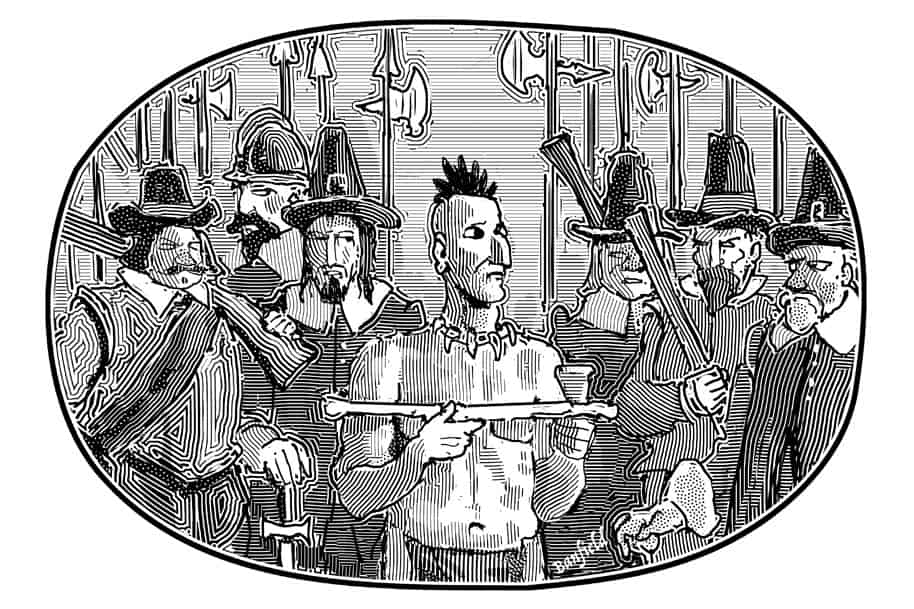

Probably Philip was using the proceeds of the land sales to buy guns. His elder brother Alexander had died while under suspicion of hatching a similar plot. The war would be fought not with bows and arrows but with relatively advanced flintlock muskets. The Wampanoags had grown dependent on firearms for hunting and as marksmen were at least the equals of the settlers.

A genuine conflict over sovereignty set the war in motion. In January 1675 John Sassamon was pushed into a hole in an icy pond. He was an Indian convert to Christianity, a scribe, a translator, a Harvard man, and possibly the most literary of the Wampanoags. He may have been killed for mis-transcribing a last will and testament dictated by Philip in such a way as to transfer certain of the chief’s properties to himself. More likely his mistake was to have betrayed Philip’s military plans to colonial authorities. Rather than request that suspects be handed over, those authorities seized three of Philip’s Indian confidants and sentenced them to be hanged. With this, Plymouth made it evident they considered the Wampanoags their subjects, no longer a sovereign nation. They had already forced Philip to sign documents to that effect.

According to Nathaniel Philbrick, Philip started the war with only 250 soldiers. That was not enough to fight regular battles with, and Philip worked instead by torching towns. Escaping his peninsular redoubt of Mount Hope (now Bristol, Rhode Island) in the summer of 1675, he made for the center of the state. There he linked up with his Nipmuck and other allies, who provided him with fresh fighters, perhaps thousands of them. They killed civilians or enslaved them, including Mary Rowlandson, a Massachusetts minister’s wife whose account of her captivity became the first American bestseller. Sudbury, Deerfield, Hatfield, Andover, Hingham, Weymouth, Haverhill, Bradford, Woburn—each day seemed to bring word of a new conflagration or massacre.

Plymouth authorities suspected that many Indians silently sympathized with Philip. Almost 200 noncombatant Indians who surrendered on a promise of amnesty were shipped to the Spanish Caribbean as slaves. The Christian Wampanoags of Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket had long been lost to Philip. They were able to sit out the war as neutrals. But Christian Indians closer to the conflict fell under suspicion and were confined, at least in the early months of the war, to Deer Island in Boston Harbor.

A popular hero of the war’s early days was Samuel Moseley, a rampaging, let-God-sort-’em-out pirate given to burning wigwams and terrorizing civilians. The effect of this kind of warfare was to drive many unaffiliated and uncommitted Indians in the region into at least passive support for Philip and to spread the violence into the territory of all six of today’s New England states. At the very end of the war, Plymouth authorities captured King Philip’s nine-year-old son. They anguished publicly and consulted Deuteronomy and 1 Kings over whether to release him or to execute him on the grounds that “the children of notorious traitors, rebels, and murderers…may be involved in the guilt of their parents and may, salva republica, be adjudged to death.” In the end they sold him into slavery.

In considering the Pilgrims’ conduct in King Philip’s war, one must bear in mind the 17th-century context in which it was fought. In Europe, the early and mid-17th century, for all its economic dynamism and cultural fecundity, was spectacularly violent—more violent than any period until the early 20th century. The conflicts of the late 17th century in North America (including the Salem witch trials of 1692-93) may have arisen as the passions of Europe’s religious wars arrived late to a provincial place. What Europeans did to American Indians at Fort Mystic in 1637, for instance, was not worse than what Germans had done to Germans at the Sack of Magdeburg earlier in the decade. In recent decades, though, Americans have been trained to read every such incident as “racial,” in a way that makes it harder for them to understand their country’s origins, to say nothing of celebrating them.

In a Different Light

The George Washington university historian David J. Silverman, disinclined to view the Pilgrim colony as an improvement on what preceded it, asks in This Land Is Their Land (2019): “Why should a school-age child with the last name of, say, Silverman, identify more with the Pilgrims than the Indians?” His book is really two books in one. As an attack on what Silverman calls the “Thanksgiving Myth”—the traditions through which Americans have celebrated the encounter between Pilgrims and Wampanoags as a friendly one—it is tendentious and poorly documented. As an attempt to retell the story of Plymouth from the Wampanoag perspective it is profound, undogmatic, and, in places, dazzling.

The book is marked from start to finish by the cant of the academy (“Englishmen…defined difference as inferiority”), by browbeating (“the fundamentally racist notion that indigenous Americans had experienced little historical change before the colonial era”), and by the gushing over commonplace civilizational achievements (“[t]he expansion of maize was a stunning feat of human engineering”) that one expects from an academic historian who got tenure in this century. We have lately reached the point at which political correctness is no longer a set of tics or partisan clichés that identifies certain historians but the lingua franca of the entire academy. There is little point in tormenting a reader with a long list of offenses committed in its name.

The Wampanoag perspective to which Silverman hopes to do justice has never been ignored. It may have been harder to establish because the Wampanoags had no written language until the Europeans arrived, but it is not clear whether their illiteracy has done more to hide their virtues or their vices. Yes, the knowledge that the Pilgrims opened Indian graves in the days after their landing does put the Indians’ early hostility in a different light. But we know that fact only because William Bradford, with his Puritan conscience, scrupulously recorded it. It is through a memoir left by Rhode Island’s deputy governor John Easton that we know of Philip’s beautiful indictment of English ingratitude. (“We endeavored,” Easton writes, “that they should lay down their arms, for the English were too strong for them. They said then that the English should do to them as they did when they were too strong for the English.”) In 1878 at the urging of Zerviah Gould Mitchell, a descendant of Massasoit, the Civil War colonel Ebenezer Weaver Peirce composed a highly competent volume recounting colonial events from Massasoit’s point of view.

Starting in the 1960s, a few developments transformed this perspective from a perennial dissenting view into the dominant academic paradigm in early American history. Revisionist historians began writing inspired briefs on behalf of the “Indian side,” culminating in Francis Jennings’s The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (1975), a bravura attack on historians of the northeastern Indian wars from Francis Parkman to Samuel Eliot Morison. Today anti-colonial historians have colonized American history departments to a greater extent than Europeans managed to colonize the Americas. If there is still a “Thanksgiving myth,” then Silverman is recounting it, not debunking it.

The history of Plymouth Colony was part of the ferment of the 1960s and ’70s. Silverman opens his book with an account of the 350th anniversary of the Mayflower landing in 1970, at which the Wampanoag Frank James saw his speech canceled when he tried to turn it into a protest. “This action by Massasoit,” James had planned to say, “was perhaps our biggest mistake.” By this James presumably meant the decision to welcome the Pilgrims in the first place, rather than to fight them on the beaches.

Massasoit appears in most of our histories up to the 20th century as a kindly and noble man who laid the basis for a lasting peace with European settlers, a peace frittered away after his death by his hothead son Philip. As noted above, there have always been dissenters from this view. For Washington Irving, Massasoit was to be praised as “a firm and magnanimous friend,” but Philip belonged to the highest order of heroes:

[W]herever, in the prejudiced and passionate narrations that have been given of it, we can arrive at simple facts, we find him displaying a vigorous mind; a fertility in expedients; a contempt of suffering and hardship; and an unconquerable resolution; that command our sympathy and applause…. He was a patriot attached to his native soil—a prince true to his subjects and indignant of their wrongs—a soldier, daring in battle, firm in adversity, patient of fatigue, of hunger, of every variety of bodily suffering, and ready to perish in the cause he had espoused.

Herbert Milton Sylvester takes Massasoit as well-meaning and naïve. “[H]is simplicity was not shared by any member of his family,” Sylvester wrote. “Alexander, Weetamoo, and Philip were wiser in their generation than Massasoit.” (Weetamoo, Alexander’s widow, became a powerful leader in Philip’s uprising.)

Silverman has much more to offer than this. He asks us to understand Massasoit—whom he calls by his tribal name, Ousamequin—not as a good guy or a bad guy but as “a great leader every bit as ruthless as those who sought to undermine him.” This requires understanding the way the balance of power had been shifted by the epidemic that hit New England on the eve of the Mayflower’s arrival. Massasoit’s Wampanoags were nearly extinguished as a people. The Pilgrim newcomers found most of the Wampanoag cornfields going back to forest. To complicate matters, the Wampanoags’ neighbors and bitter rivals the Narragansetts, for reasons unknown, had emerged from the epidemic largely unscathed. So by 1620 Massasoit, until recently a great warlord, had come under constant attack, and was paying the Narragansetts tribute.

The immigrants proved to be Massasoit’s deus ex machina. His outreach to them, Silverman tells us, was “a strategic response.” As allies, the Pilgrims were not numerous, but they were growing and, rightly managed, they could give him access to firearms. Massasoit, naturally, could have wiped them out at almost any time in the early days. When the second Pilgrim ship, the Fortuna, sailed into Wampanoag waters in 1621, he was probably glad he hadn’t. Whether the Pilgrims were as special a group of settlers as Adams and Webster thought, the Wampanoags would certainly have seen that they were a different kind of colonist. Armed only modestly, bringing their women and children with them, they didn’t look like the traders and buccaneers the Indians were used to.

But the English were not to be taken lightly. One of the winning things about Francis Jennings’s work was his sense of how non-military institutions could serve as more efficient tools of conquest—especially the legal system, which trapped Indians in a forest of casuistic mumbo-jumbo. Much of the English conquest was carried out through the drawing up of title deeds. Thus can an invasion take the form of a friendly mass migration without many of its participants even realizing that an invasion is what they are carrying out.

In 1640, Norwalk Indians sold the whole of coastal Connecticut between Norwalk and Westport for “ten jew’s-harps and ten fathoms of tobacco.” It has been common to consider the Indians idiots for assenting to such deals. But the idea that Indians knew what they were signing is preposterous. As an illiterate people, they could have no conception of the irrevocability of a few marks scratched on a piece of parchment. They cannot possibly have thought that they were surrendering all rights to their property because, where they could, they spelled out explicitly that they weren’t, Silverman shows. “[S]ome deeds required the English to pay tribute to the local sachem [or chief],” he writes, “as if they were joining Wampanoag society rather than buying the land from out of it.” In the end, King Philip didn’t trust the English enough to negotiate a peace accord.

Ultimate Consequences

Like most peoples throughout history who have been fast-talked out of their birthright, the Indians felt for a long time that they had got a terrific deal. They seemed to be living better than they ever had. Suddenly, for instance, many Indians possessed horses. But Silverman notes that “within a generation they would have little land left on which to use the horses to ride or plow.” The horses had been bought with wampum, a real currency limited in supply by the skill needed to make it, and backed by valuable fur trade, especially in beaver. But soon their hunting grounds were sold away, and eventually overhunting killed off the beaver. The Indians had not been living better, it turns out. They had been living off the sale of their capital, and had not noticed, because the most valuable parts of a people’s capital are often hard to quantify.

Perhaps Squanto knew better. A sociable brave to modern-day schoolchildren, a double-dealer and con artist to historians, he became an enemy of Massasoit, who suspected him, probably rightly, of designs on his power. Silverman speculates that long residence in England gave him a sense of

the long-term danger posed to the Wampanoags by Europeans, not just those in the tiny colony of Plymouth, but the multitudes who were bound to follow…. Only he and Epenow among the Wampanoags had witnessed firsthand the vast populations from which the English hailed and which allowed them to keep pouring warm bodies into colonial death traps overseas.

Hence, perhaps, the ruthlessness of Epenow in dealing with Europeans, once he had tricked them into returning him to his homeland.

Real expert opinion on migration always contains a large dose of civilizational pessimism. When an African boat with eight migrants in it pulls up to an Italian fishing vessel in the Mediterranean, a progressive politician sees a heartbreaking story on national television and calls for more lenient refugee laws. A populist politician understands that any invitation offered to those eight will also be heard by the billion young people the continent will add in the next generation. A version of that story was what happened when the Pilgrims landed. Massasoit was like a progressive. His foes were like populists, who viewed his friendliness to the Pilgrims as playing with fire.

Silverman’s Wampanoag-centered view of the 17th century is more pessimistic than most about what the possibilities for cultural harmony were. Perhaps this has to do with our changing times. Nathaniel Philbrick’s Mayflower came out 14 years ago. It has a Clinton/Bush-era focus on diversity as a social good, even as a “strength,” and assumes it can be maintained so long as the right leaders, men of peace, are in charge:

When Philip’s warriors attacked in June of 1675, it was not because relentless and faceless forces had given the Indians no other choice. Those forces had existed from the very beginning. War came to New England because two leaders—Philip and his English counterpart, Josiah Winslow—allowed it to happen. For Indians and English alike, there was nothing inevitable about King Philip’s War.

Where Philbrick is a liberal, Silverman has a more “woke” or “populist” view of intercommunal relations. Generally one side or the other controls the peace, and if that stronger side is not inclined to behave responsibly it will raise the price of peace to the point where peace is not worth having. By 1675, the Europeans controlled the peace.

In this more sensible-seeming reading, King Philip’s decision for war does not contradict or discredit Massasoit’s decision for peace. Each was recruiting an outsider to help restore balance to a rivalry in which he was losing ground. Massasoit needed the Pilgrims to defend him against stronger tribes in his neighborhood. Philip needed his Indian neighbors to defend him against overbearing Europeans.

King Philip had one extraordinary advantage as war raged in the autumn of 1675: The settlers did not know how to fight an Indian war. They couldn’t cross a swamp, they couldn’t travel silently in woods, they couldn’t keep warm outdoors. Indians won battle after battle.

But the victories were Pyrrhic. Plymouth and its allies in Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, and Connecticut were connected to global trade networks and could import food, while the Indians were an agricultural people a long way from their fields and stores. King Philip’s troops may have been winning. But they were also starving.

The English controlled the technological platform of the war. However formidable Indians were at firing guns, they could not manufacture them. The best hope of the Wampanoags and their Nipmuck, Narragansett, and Abenaki allies was to enlist the ferocious Mohawks of the upper Hudson, with their thousands of fighting men. But the Mohawks’ ferocity (and independence) rested on arms obtained from Albany merchants whom they could not afford to alienate. They entered the war against King Philip, suddenly and to devastating effect.

Finally, the English had cohesion, however you choose to name it: solidarity, like-mindedness, uniformity. The Indians had diversity. That meant some fought with Philip and others fought against him. The Christians among them were an important source of intelligence to the English. War split up not just families but, among the tribal leaders, marriages. King Philip was driven eastward, back across Massachusetts, to his homeland and his fate.

“If the Wampanoags are as much our fellow Americans as the descendants of the Pilgrims,” Silverman asks, “and if their history can be as instructional and inspirational as that of the English, then why continue to tell a Thanksgiving myth that focuses exclusively on the colonists’ struggles rather than theirs?” The answer, as noted, is that we no longer do tell that myth, and haven’t for years. Once we have dismissed the Puritans’ religious claims, once we lose interest in the way their democratic intuitions, from the Mayflower Compact onward, anticipate our own democratic institutions, then we are left with a tale of increasing tensions between two ethnic communities that eventually exploded into war. Every prejudice that has been schooled into Americans over the past half-century would prompt them to root against the Pilgrims.

But that is no longer the only reason we don’t look at Plymouth from a Pilgrim perspective. Of the two communities that confronted each other in New England 400 years ago, it may now be the Indians, not the Pilgrims, who most resemble today’s Americans. The Wampanoags were divided between, on one hand, cosmopolitans like Massasoit, who believed that there was room for a mosaic of peoples in southeastern Massachusetts, and, on the other, skeptical provincials like Philip who lost faith in that ideal. They lacked the cohesion to stand up against a resolute rival.

A remark often bandied about today is Adam Smith’s to the effect that “[t]here is a great deal of ruin in a nation,” by which he meant that it takes a much greater set of misfortunes to destroy a nation, and over a much longer period of time, than we commonly realize. It is not actually true. The Wampanoags went from dominance and confidence to a point of no return in about 55 or 60 years. Suddenly they were losing population, and abandoning old values, too. Each problem fed on the other in a dangerous process. Once a people begins debating how much ruin there is in a nation, that process is already well underway.