Books Reviewed

A review of Napoleon: A Political Life, by Steven Englund

Napoleon Bonaparte died in May 1821. He had spent the last five-and-a-half years of his life as the involuntary guest of Britain's Royal Navy on St. Helena, a small, wet, and windswept island in the South Atlantic. During this bleak enforced exile he devoted much of his ample spare time to dictating complaints about his treatment, and to constructing elaborate justifications for his eventful political life. His companions collected and published several versions of these "memoirs."

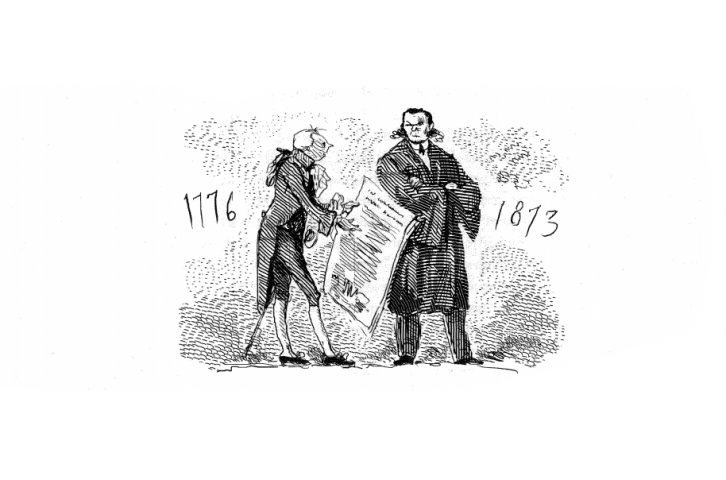

In 1823, Thomas Jefferson read one of these collections. Reviewing it in one of his wonderful exchanges of letters with John Adams, he went back on his earlier assertion that Bonaparte deserved whatever he got ("His sufferings cannot be too great," he had written to Albert Gallatin in 1815), and commiserated to the extent of saying that it was inhumane (of the British and their allies) to have inflicted this lingering death on him. But Jefferson did not at all retract his earlier and decidedly unfavorable judgments of Napoleon's character; nor did he think Napoleon deserved much less punishment than he received. In his letter to Adams, Jefferson concluded that Napoleon had by his own words proved that he was "a moral monster, against whom every hand should have been lifted to slay him."

Steven Englund, an American scholar who teaches French history to university students in Paris, has a more ambivalent view of Napoleon. He thinks that those who revile Napoleon "fail to explain his hold on contemporaries," not to mention his fascination to later generations. Discussing this fascination, he alludes to Jefferson "seeing Napoleon on St. Helena in a different and more sympathetic light" than previously. We have just seen that this is a misleading summary of Jefferson's view. The continuing fascination with Napoleon is something worth pondering, but there is no reason we cannot do that—indeed, we can probably do it more successfully—if, with Jefferson (who, remember, loved France), we maintain the ability to see the monstrosity of the man and his politics. We would not have to base this ability on a "remorseless wish to cut Napoleon down to size" that Englund sees in many "Anglo-Saxon writers" (as the French often call us). In fact, we could confidently base it only on an effort to see moral and political things as they are, with their vileness, their mediocrity, and their grandeur. To understand healthy politics, we have to understand political diseases.

Englund explains contemporaries' and later generations' fascination with Napoleon by asserting that there is something unique and admirable in Napoleon's life. The unambivalent revilers, he says, fail "to grasp the power of the man's uniqueness, and the good he also did." Yet he is an assiduous and painstaking historian, and his finely crafted and comprehensive biography gives us plenty of evidence of the bad, and little if any evidence of the good, in Napoleon's political life. His book often lets us see fairly precisely what the bad consisted of. So, apart from avoiding uncomfortable scenes when he gives dinner parties to other historians in Paris—he recounts one such scene in his "Bibliographical Comments"—it is not clear why he is so insistently ambivalent. Having collected so much evidence for the case against Napoleon, why does he resist connecting the dots?

Englund quotes Napoleon's often-repeated "imperial sigh" with which he justified his aggressiveness and constant wars: "Five or six families share the thrones of Europe and they take it badly that a Corsican has seated himself at their table. I can only maintain myself there by force; I can only get them used to regarding me as their equal by keeping them in thrall; my empire will be destroyed if I cease being fearsome…." Englund spots that this "cunning exercise in self-pity" is also the classic "rationale for an aggressive child"; Napoleon falsely assumes that a constant series of wars was needed "to confer legitimacy on the Emperor, that he was not safely on his throne unless he was mounted in the saddle at the head of the Grande Armée." Later he shows that the European War of 1812—in which a million or more men died for no good reason—clearly resulted from this Napoleonic aggressiveness, coupled with an equally childish dialectic of vanity between Emperor Napoleon and Czar Alexander.

Englund links Napoleon's sense of unique greatness, godlike self-sufficiency, and cool detachment to "Aristotle's portrait of the 'great-souled' man who is indifferent to opinion." This is seriously inaccurate. The "great-souled" man as described by Aristotle is not indifferent to honor by those whose good opinion is worth having, and he is open to friendship that helps confirm his own moral excellence. He is not a tyrannical bully who smothers his insecurity with belligerence, disdains friendship, and craves glory. What Englund is discerning in Napoleon is not megalopsychia. It is megalomania. (Jefferson saw this and its political dimensions very clearly: "After destroying the liberties of his country, he has exhausted all its resources, physical and moral, to indulge his own maniac ambition, his own tyrannical and overbearing spirit.")

In this context Englund draws our attention to Napoleon's last public utterance, the last line of his will: "Nothing to my son, except my name!" Englund may be right to identify this narcissism and megalomania with the "will to power" analyzed by Nietzsche (who, as he notes, claimed Napoleon for one of his own). But this identification is not well calculated to improve Napoleon's reputation as an admirable statesman, except perhaps among "postmoderns" prepared to admire any commitment as long as it is made with enough style and irony.

* * *

Napoleon's unhealthy political psyche was complemented by an illiberal modern political philosophy, with which he explained and justified his dictatorial politics. More than previous biographers, Englund focuses on the young Napoleon's reading and writing. In Valence, in his first posting as an artillery officer in 1785-1786, he would skimp on food in order to buy books on history and politics, which he passionately consumed. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a particular favorite. Englund shows that what Napoleon learned from Rousseau—and maintained throughout his career—was fully compatible with a Hobbesian way of thinking: the natural equality of men consists of their self-interested drive for domination, so the State, although based on a general will (and not on divine right monarchy), must be strong and active, even absorbing religion into itself. (Priests are too ready "to foment rebellion among the people against injustice"!) The purpose of government is not to secure justice and the natural rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but to "permit each person to taste sweet tranquillity, to find himself on the road to happiness." Quiet despotism is the goal, and patriotic glory, foreign wars, and domestic political repression are legitimate means to that goal.

Englund does not raise any alarm about these illiberal, Hobbesian-Rousseauan roots of Napoleon's politics. He is also too uncritical of the Hegelian fruit that grows from these roots: Napoleon's attempt to suppress partisan political conflict in France, in favor of patriotic unity supporting the State. He correctly points out that Napoleon was not the only Frenchman in his day (and there remain many in ours) to whom "Anglo-Saxon" constitutions with limited government and loyal but robust opposition parties are "an invitation to social dissolution in a free-for-all of market forces and factional or corporatist interest." This distrust of politics and its absorption into the State (which Hegel so much admired in Napoleon) may or may not have been necessary in the France of Napoleon's day. But, contrary to Englund's suggestion, this distrust, and the consequent construction of a centralized technocratic State for "a post-political society," is not a "liberal vision."

In Napoleon, the combination of a megalomaniac personality with a radical, illiberal political philosophy was lethal. It destroyed ten million human beings, set back the cause of political liberty in Europe, gave political philosophy a bad name, made conservatism reactionary, and boosted the world's already strong propensity to equate might with right. What is there to set against this enormous debit? Not a lot. Maybe we can agree with Englund that Napoleon was an admirable city planner, with an un-Napoleonic and "profoundly human tendency to hesitate, back down, accept criticism, defer to opinion, tolerate indecision, change his mind, evolve his thinking." So there's a career alternative for you, M. Bonaparte! But there were larger issues. Outside France, as Englund recognizes, the 19th-century European liberal nationalism (which in any case was not dependably liberal) that is often credited to Napoleon owed more to the local resistance to French conquest than to the inspiration of French ideals, which in practice were generally subordinated to French interests. Within France, politicians and citizens are still wrestling with the centralized State that Napoleon bequeathed as a "solution" to political conflict, and that has been justified ever since Napoleon (incorrectly, Jefferson would assert) as a necessity for France's self-defence. In any case, even if centralization has been desirable or necessary for France, it is well known that it was originated not by Napoleon but by the ancien régime, so we had better give credit where credit is due, if any is due.

Could it all have been otherwise? Hypothetical history can be annoyingly speculative, but sometimes it can be useful for seeing what did happen more clearly.

First of all, could those massively destructive wars have been avoided? Englund's accounts show how, during Napoleon's years in power, a durable European peace, honorable to France, could have been arranged, if Napoleon had been more peacefully inclined. Englund tries to apologize for Napoleon's bellicosity by drawing our attention to the contemporary climate of opinion, which, unlike ours, celebrated military conquest and glory. But that simply won't do, given the number of contemporary condemnations (in France as well as elsewhere) of Napoleon's egregiousness.

* * *

Could the French Revolution itself—the violence of which made Napoleon seem necessary—have unrolled more moderately? It is true that circumstances in 18th-century France made liberal reforms more difficult there than in Britain and America. But many historians—French as well as "Anglo-Saxon"—have shown that the violent Revolution arose not out of historical inevitability, but from the indecisive policies of the King's governments, and, especially, from the histrionic insobriety of the critics of these governments. It was not just extreme social resentments, it was also flawed political philosophy and radical chic that led the Revolution to replace the absolute sovereignty of divine right monarchy with the absolute sovereignty of democratic administrative tyranny. It was unfortunate but not preordained that in their constitutional thinking so many French revolutionaries—like the young artillery officer who would soon join and dominate them—were captivated by bad political ideas and ignored good ones, preferring "Lightning to the Light" (as Gouverneur Morris reported from Paris).

Finally, could Napoleon have been a French George Washington? During his exile on St. Helena, Napoleon explained why he had consciously rejected this possibility:

If [Washington] had been in France, with domestic disorder and the threat of foreign invasion, I defy him to have been himself. If he had, he would have been a fool and prolonged the unhappiness of the country. As for me, I could only have been a Washington with a crown, amid a congress of conquered kings. Only under such circumstances could I have shown his moderation, wisdom, and disinterestedness. These I could attain only by a universal dictatorship, such as, indeed, I strove for.

Englund does not go as far as Napoleon, but he does share some of Napoleon's doubts. He asks: "would French political circumstances and traditions have sustained" a Washington?

Well, by 1799 (when the 30-year-old Napoleon came to power), maybe not, but if Napoleon was the alternative, then surely a Washingtonian approach would have been worth a try, even then. Napoleon's pre-emptive strike on liberal politics ruled out the experiment. He didn't want to try to be a Washington, and he made sure that no one else could try. Englund lets us see that there were liberal roads that the government could have taken even during Napoleon's rule, if Napoleon had wanted to. And after all, when Napoleon had finally been removed from the French political scene, what happened in France? An experiment in constitutional monarchy—which was what pre-Revolutionary liberals had favored as the first step in France's political reform. This suggests that France's more liberal political life could have begun—and, without having had to go through the Jacobin and Napoleonic experiences¸ more easily and promisingly begun—at any time before 1802, when Napoleon chose to rule it out and insisted on being made First Consul for Life. France could have set a good example to the rest of Europe, and saved the whole world a great deal of trouble.