For Americans, too, in the beginning was the word.

Unlike many countries, we have a record of our beginnings. We can name the day in July, and the men who were in the room, because the birth of our nation comes with its own signed birth certificate. We mark the Fourth every year with speeches and fireworks, and revere the Declaration of Independence itself, erecting for it a “shrine” in the rotunda of our National Archives.

Historian Pauline Maier tried to capture the sense of reverence that has built up around our founding charter by titling her book on the Declaration, American Scripture. And so it is, both our Genesis and our Golden Rule. But even as there are many books of the Bible, there are many documents through which we can chronicle the history of the United States. And no single collection brings together more of these broadsides, pamphlets, posters, dispatches, telegrams, diaries, speeches, notes, and letters than the magnificent Gilder Lehrman Collection, which opens its new home in June at the New-York Historical Society in New York City.

* * *

Along Central Park West, the New-York Historical Society’s stout, stately presence is immediately recognizable. It sits nestled between 76th and 77th streets, built in the neoclassical style that we Americans like to reserve for museums, libraries, and columned temples in the nation’s capital. Entering through its side entrance on 77th Street into a high-ceilinged rotunda, you are escorted down the stairs to the new location of the Gilder Lehrman Collection. Here, among the staff offices and a small library, you are shown to the Reading Room, a modest boardroom with table and chairs. A large, framed 1863 poster demands your attention as you enter. It declares “Men of Color, To Arms! To Arms! It’s Now or Never.” It reminds you of the power of the word.

On the table, several plain manila folders, each containing a select piece of correspondence, have been casually laid out. Seeing original letters for the first time, it’s the small details that strike you. The way a letter is written out cleanly, evenly, in some cases on paper held horizontally and folded over. The envelopes of 150 years ago look so familiar, lacking our modern zip codes but with stamps and post office cancellations that look the same. To read the letters themselves is to encounter, not the dead hand of the past, but the living voices of our fellow Americans.

The penmanship can be difficult to read, even in a “fair copy”—and one could read, instead, the typed transcript that accompanies each—but there is something electric to holding the original. James G. Basker, the president of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History (the Collection’s sibling organization), and Ann Whitney Olin Professor of English at Columbia University’s Barnard College, is right when he says, “such documents can be a stimulus to the imagination. They can ‘humanize’ history.” And indeed there is something beguiling to old John Jay from The Federalist when he’s writing about a “conch shell beauty” he saw at the tavern one day. But the humanizing of history is more than such private moments.

Preserving the tokens of our past touches something of the religious aspect of human nature. It is present in the way we might make a pilgrimage to Independence Hall, or gaze upon Jefferson’s writing desk, or the contents of Lincoln’s coat pockets at Ford’s Theater that final night, the relics of a fallen martyr. These tangible things connect us to our past, a profound physical continuity that no textbook account can satisfy. Historical documents offer a still closer connection to the past. At their best, in the Declaration of Independence or in the Gettysburg Address, they not only reflect our country but define it, by articulating the self-evident truth that unites all Americans past, present, and future.

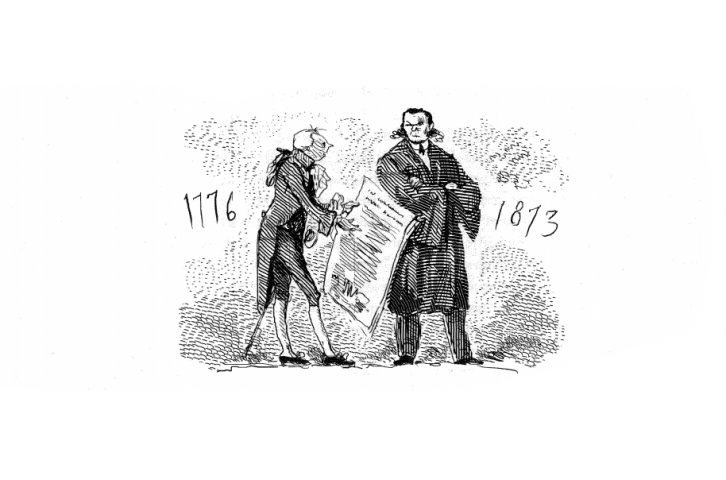

And so, while one can find everything from a letter signed by Christopher Columbus to President Ford’s pardon of President Nixon, much of the Collection centers around the American Revolution and the Civil War. This is as it should be. It is in these two great struggles, the first and last acts of the same drama, as Harry V. Jaffa has called them, that the central idea of equality comes most sharply into focus. The idea underlies a letter to a fellow plantation owner in which George Washington vows he will possess no more slaves and hopes that Congress will abolish slavery. It is there when John Quincy Adams agrees to represent the slaves of the Amistad before the Supreme Court. It echoes from the “Am I not a man and a brother” on an abolitionist campaign token to a placard declaring “I am a man,” carried in Martin Luther King’s last march for civil rights a century later. These simple things move us, remind us, call us back to first principles.

The most lasting image from the Collection is not a document at all, but the contents of a small, unassuming box. It feels heavy. Opening it reveals coils of iron, dented into shape by a hammer. It is a miniature set of iron manacles, manacles for a slave child.

* * *

Lewis Lehrman began collecting rare books and manuscripts while still in college, picking up what interesting items he could find with what money he could spare. “Today one might have to pay five to ten thousand dollars…maybe more,” says Lehrman, “but then you could buy documents like that for five, ten, and twenty dollars.” Later a successful businessman, he ran for governor of New York, and today is Chairman of L.E. Lehrman & Co., a private investment firm. He teamed with Richard Gilder, a fellow philanthropist and a leading figure in the world of investment banking (his firm is Gilder, Gagnon, Howe, and Company). Together, they founded the Gilder Lehrman Collection in 1991, and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History in 1994.

“We had a great partnership. Dick and I had the same goal: [the] largest private collection of historical documents ever assembled…. We had total flexibility and we could move quickly and as rapidly as the market would allow.” But the Collection would not be just any old documents. The two agreed that they had little interest in letters, say, from Lincoln dealing with the mundane details of his law practice. They wanted the letters that explained why this Illinois lawyer returned to politics in the 1850s to fight the expansion of slavery. Such documents reveal ideas: the ideas that lie at the heart of self-government, the ideas for which Americans have fought and died. “To die for ideas…,” says Gilder softly. “You realize the great sacrifice and why…. And then you feel, well, if I feel this way, other Americans should too, and other people around the world.”

The Collection did not neglect the proverbial little old lady rumored to have some rare treasure hidden in the attic; but most of its holdings came the traditional way, at auction and through private dealers. One of its best finds, which Lehrman considers their greatest purchase, came from a library with a national reputation. “It’s the papers of the great revolutionary war hero Henry Knox, and they either weren’t in the position or didn’t want to be in the position to handle this archive the way it needed to be handled.” Today, their one-of-a-kind collection contains more than 60,000 items.

* * *

From the beginning, the Collection sought, in Lehrman’s words, to counter the growing sense that “American history had been lost,” that the proper, clear-eyed “study and celebration of American history,” had been abandoned. While forming the Collection was itself “a financial affirmation of the importance of American history, it was never far from our minds,” says Lehrman, “that American history, in order to be revived, had to be taught, and that it had to be taught from the documents themselves.”

The Gilder Lehrman Institute works to reconnect Americans with their history through a variety of educational programs, making historical documents available through a searchable online archive, books, and teacher materials. It sponsors fellowships, teacher seminars, public lectures, exhibits, awards, weekend courses or “Saturday Academies” in American history, and four-year, college-preparatory “History High Schools” emphasizing American history.

To be sure, this laudable educational project faces the challenge of finding good historians and political scientists willing to appreciate the significance of American political and intellectual history. In the past quarter-century, professional historians have so greatly favored social history at the expense of the more traditional kinds that there is an occupational bias against the Institute’s approach. But an attention to original documents in the classroom can promote careful reading by students themselves. Perhaps students schooled in the primary sources of our history will come to judge their teachers’ interpretations in light of the documents rather than reading the documents (or worse, ignoring them) solely in light of their teachers’ interpretations. After all, anyone can quote scripture.

* * *

Those visiting the New-York Historical Society later this year will have a chance to see an ambitious exhibit on “Alexander Hamilton: the Man who Made Modern America,” thanks in part to the Gilder Lehrman Institute and its own energetic executive, James Basker. Marking the two hundredth anniversary of Hamilton’s death (in the duel with Aaron Burr) and the Historical Society’s birth, Basker has sought to reinvigorate this venerable old New York institution by initiating one of the largest exhibitions ever devoted to a single historical figure, and certainly the largest ever devoted to Alexander Hamilton.

Under the expert curatorship of Richard Brookhiser, whose elegant book Alexander Hamilton, American is a modern classic, the exhibit will span the entire ground floor. Visitors will see the actual pistols fired upon the heights of Weehawken, and the letters that precipitated history’s most infamous duel. Multi-media presentations will also impress upon visitors the profound living legacy of this dynamic founder. George Will overstated this legacy, but not by much, when he wrote, “If you seek Hamilton’s monument, look around. You are living in it. We honor Jefferson, but live in Hamilton’s country.”

“Alexander Hamilton: the Man who Made Modern America” runs from September through February. The Gilder Lehrman Collection is on deposit at the New-York Historical Society for at least three years and is available to scholars, teachers, students, and the general public. It is a light not hidden under a bushel basket but shining forth to call all Americans back to their first principles.