Books Reviewed

Michael Young’s novel The Rise of the Meritocracy, published in 1958, was written in the voice of a historian in 2033 describing a meritocratic Britain where talent was identified, nurtured, and rewarded regardless of ethnic or social origins. The result? The gulf between the elites and ordinary Britons had widened and become far harsher.

In the old days, Young explained, upper-class Britons knew that their talents had nothing to do with the advantages they enjoyed. “The upper-class man had to be insensitive indeed not to have noticed, at some time in his life,” Young wrote, that among the servants and common workmen that he encountered “was intelligence, wit, and wisdom at least equal to his own.” The servants and common workmen had noticed the same thing and could rightly say to themselves, “I could have done anything. I never had the chance. And so I am a worker. But don’t think that at bottom I am any worse than anyone else.”

The shift to a meritocratic society relieved those on top of any doubts of their native superiority and stripped those on the bottom of excuses. Here are other direct quotes from Young’s book, written in the mid-1950s, that are uncannily accurate about both Britain and America in 2021:

“Today, the elite know that…their social inferiors are inferiors in other ways as well—that is, in the two vital qualities, of intelligence and education, which are given pride of place in the more consistent value system of the twenty-first century.”

“Today all persons, however humble, know they have had every chance…. Are they not bound to recognize that they have an inferior status—not as in the past because they were denied opportunity; but because they are inferior?”

“Some members of the meritocracy…have become so impressed with their own importance as to lose sympathy with the people whom they govern.”

Young foresaw what I believe to be a central problem of our age, amended to fit America’s situation: the development of cultural and economic elites, overwhelmingly white, isolated from, and openly contemptuous of, the lives of ordinary Americans, whether white, black, or Latino.

* * *

The quotations from Young are to be found in Harvard political philosopher Michael Sandel’s The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?. I will skip to the bottom line: Sandel has given us an important meditation, starting from first principles, on how to think about human merit and a meritocratic society. Even someone who has been worried about the downsides of meritocracy for a long time (my book with Richard Herrnstein, The Bell Curve, was published 27 years ago) found new ways of thinking about the issues. Sandel is also a writer of the Left whom people of the Right can read without dread. He gives fair treatment to alternative perspectives and engages readers rather than lecturing them.

The first step in deciding what one thinks of meritocracy is deciding what one believes about personal responsibility. I suspect most of us occupy center ground: we assume a place for free will but also acknowledge limits. The most obvious limits have to do with physical and cognitive abilities. None of us can become starters on a major league baseball team or get a Ph.D. in mathematics unless we are blessed with talents that are wholly outside our control. But the limits extend far beyond those that keep us from being superstars. Since the middle of the 20th century, cognitive ability has become an all-purpose advantage in the labor market for a far wider range of occupations than previously. But it is not an advantage we can enjoy through hard work. Nobody can increase his own I.Q. significantly. That’s an empirical statement with abundant proof. High I.Q. in the 21st century is an extremely valuable and wholly unearned gift.

* * *

What about our personal responsibility—our merit—when it comes to taking advantage of our unearned gifts? How much credit or blame do we deserve for our industriousness, conscientiousness, self-discipline, charm, and other traits that contribute to success in life? In each case, we must recognize some degree of luck and constraint. I have unexceptional interpersonal skills, for example. I could improve my interpersonal skills to some degree, but I don’t kid myself that I could ever be a Bill Clinton or Bill Buckley. I have also worked unusually long hours all my adult life, but self-discipline has had nothing to do with it. I’ve been enjoying myself. Everyone has similar reasons for saying to oneself both “it’s not my fault” about some traits and “I actually can’t take much credit for it” for others. We are being realistic in doing so. And yet I nonetheless have a sense that I have exerted myself in ways that I can justly take credit for—I made rewarding choices that others with equal gifts didn’t make. That belief, valid or not in an abstract sense, is a source of personal satisfaction and as such represents the upside of meritocracy for human flourishing. More broadly, it is a good thing to give everyone a chance to fulfill his potential. A meritocratic society is “doubly inspiring,” in Sandel’s words. “It affirms a powerful notion of freedom, and it gives people what they have earned for themselves and therefore deserve.” The problem arises when people neglect their inner sense of the limits and constraints on their personal abilities. “It is one thing to hold people responsible for acting morally; it is something else to assume that we are, each of us, wholly responsible for our lot in life.”

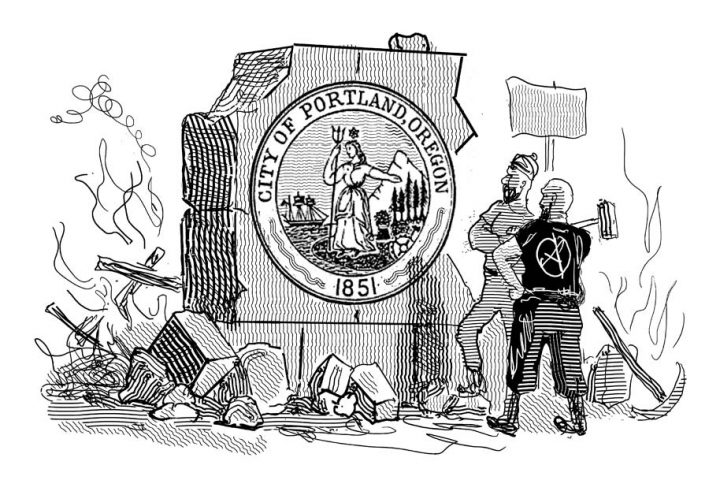

As Young predicted, far too many members of today’s elites really do believe that they deserve their place in the world. They have gotten too big for their britches. They are unseemly, albeit in different ways. The billionaire’s 30,000-square-foot home is visibly unseemly. But so is a faculty lounge of academics making snide remarks about rednecks—meaning the people without whom the academics would have no working mechanical transportation, be in the dark after sundown, have to use chamber pots, and, literally, starve. Today’s elites have a remarkable obliviousness about the lives and contributions of ordinary people that bespeaks an unseemly indifference—not to mention disdain—for those people.

* * *

But how did the elites get that way? Or have they always been that way? Sandel locates the origins of merit in Western culture in the God of Genesis and Exodus who rewarded people who behaved rightly and punished those who did not. But, he points out, the subsequent development of theology, especially Christian theology, is explicitly anti-meritocratic. We are all sinners in God’s eyes but also have equal access to God’s grace—grace that cannot be earned by good works or merit of any sort.

Sandel associates himself with Max Weber’s argument in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The Calvinist doctrine of predestination inadvertently led people to associate success in life with evidence of God’s approval and hence evidence of personal merit. Sandel sees vestiges of this “providential faith” in today’s secular elites. He elaborates this line of argument through a sequence of chapters, dividing his attention between two broad topics: the justice of meritocracy and the social desirability of meritocracy. He is worth reading about both topics, but people who reject John Rawls’s conception of justice will find Sandel’s treatment of justice intellectually interesting but unsatisfying. For me, Sandel’s discussion of the desirability of meritocracy was much more instructive. It begins with a nuanced and surprisingly stinging critique of welfare state liberalism—“luck egalitarianism,” Sandel calls it. The successful think that the welfare state makes up for the injustices of unequal gifts, but this has destructive effects.

To qualify for public assistance, [people] must present themselves—and conceive of themselves—as victims of forces beyond their control…. Liberals who defend the welfare state on the basis of luck egalitarianism are led, almost unavoidably, to a rhetoric of victimhood that views welfare recipients as lacking agency, as incapable of acting responsibly.

It amounts to “the politics of hubris and humiliation.” I braced myself for what I was sure was coming next, advocacy for full-blown social democratic redistribution, but I was wrong. Instead, Sandel gives us a chapter on the evils of the educational sorting machine followed by a chapter on the paramount importance of restoring the dignity of work. I found myself nodding in agreement throughout.

* * *

I do have a few quibbles. They are based mostly on personal observations, not hard data, but ask yourself if they match up with your own experiences.

Regarding respect for work, I agree that elites have devalued the dignity associated with non-intellectual work. Too many young people are under the impression that if they can’t be an attorney or corporate executive their only option is to be a greeter at Walmart. That mindset explains why so many blue-collar craftsmen, sometimes making six-figure incomes, have trouble finding young people who want to become apprentices. But Sandel may have spent too much time among Harvard students and too little time around young people who don’t aspire to a law partnership or a job at Goldman Sachs. Many of them have found something they enjoy doing and are employed in skilled jobs. The ones I encounter do not see themselves as victimized because their I.Q.s are closer to 90 than to 130, nor because other people with higher I.Q.s make a lot of money. As far as I can tell, the satisfactions they get from being good at their jobs are at least as authentic as the satisfactions people take from more prestigious careers. The falling percentage of people ages 18 to 29 who think college is very important (down 33% from 2013 to 2019) suggests that young people with I.Q.s that are closer to 130 than 90 may also be taking a closer look at options that don’t put them behind a desk or in front of a computer screen.

Regarding the hubris of the elites, I agree with Sandel if he is referring to the elites in Washington, New York City, Los Angeles, Silicon Valley, and Ivy League towns. I think elite hubris is far less problematic in small cities. For the past 31 years, my wife and I have lived in a small town 15 miles from Frederick, Maryland, a city of 71,000 people. Because of my wife’s civic involvement in Frederick, it’s fair to say that we have met nearly all of Frederick’s movers and shakers. Many of them grew up in the Frederick area, few of them attended elite schools, and none of them show any signs that they think of themselves as anything other than ordinary Americans. The civic life of Frederick in 2021 is energetic, optimistic, and fueled not by government but by a network of local voluntary associations. Alexis de Tocqueville would recognize it as a direct descendant of the American civic culture he described in the 1830s.

* * *

I don’t think Frederick is exceptional. The traditional American civic virtues are alive and well in small-town and small-city America. Those communities are beset by some of the new problems that afflict the nation, especially increased drug addiction and family breakdown. But they are approaching those problems as Americans traditionally did and local institutions continue to function as they traditionally did. I will repeat what I have written elsewhere, because it has been my dominant thought for the last decade: The great divide in the United States is not political or racial. It grows out of the immense difference between daily life in the big cities and daily life everywhere else. That difference amounts to a chasm dividing Americans’ experience of their country. It also lies behind the political polarization that is tearing us apart.

It is no surprise that a social democrat like Sandel and a small-government Madisonian like me emphasize different perspectives on the same problem. What’s surprising is the extent to which I admire Sandel’s positions, starting with the clarity and urgency of the question that The Tyranny of Merit asks:

What if the real problem with meritocracy is not that we have failed to achieve it but that the ideal is flawed? What if the rhetoric of rising no longer inspires, not simply because social mobility has stalled but, more fundamentally, because helping people scramble up the ladder of success in a competitive meritocracy is a hollow political project that reflects an impoverished conception of citizenship and freedom?

The contemporary American meritocracy does indeed constitute a hollow political project. It does indeed reflect an impoverished conception of citizenship and freedom. But these judgments are as consistent with the teachings of Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments as with the teachings of Rawls’s Theory of Justice. If there can be that much agreement between people who are as far apart politically as Sandel and his reviewer, common ground should be within the nation’s grasp. Somehow.