Books Reviewed

Two thousand seventeen is the year of Martin Luther, the 500th anniversary of his protest decrying the Catholic Church’s sale of indulgences. According to legend, and perhaps even in fact, he nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg on October 31—Halloween or the Eve of All Saints Day—and thereby launched the Protestant Reformation.

So the scholars are out in force this year, observing the anniversary with new books to commemorate the great man, and to invigorate debate. The Oxford University Press has issued its translation of the Berlin historian Heinz Schilling’s Martin Luther: Rebel in An Age of Upheaval, which raises the crucial matter of the Reformation’s relation to, not to say revulsion from, the secular magnificence and sensual overflow of the Renaissance. Brigham Young University historian Craig Harline’s A World Ablaze: The Rise of Martin Luther and the Birth of the Reformation focuses on the five years after the 95 Theses. Writing expressly for readers unfamiliar with Luther, Harline adopts a cloyingly folksy and familiar prose, in the manner of a high school teacher trying to make his subject palatable to students who couldn’t care less; yet his book is valuable all the same for its detailed recounting of the most significant period of Luther’s public life.

All Things Made New: The Reformation and Its Legacy by the Oxford professor of church history Diarmaid MacCulloch is a collection of occasional pieces from the past 20 years—most of formidable scholarly provenance, a livelier handful originally published in the London Review of Books—on a scattering of subjects from angels in the Reformation to the Italian inquisition. MacCulloch made his reputation with The Reformation: A History (2003), which deservedly earned high praise for its masterly scope and insight, and both are works of impressive scholarship and elegant craftsmanship. Lyndal Roper, the Regius Professor of History at Oxford, has weighed in with Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet, the most brutally honest of the Luther studies, for although she plainly reveres him, she doesn’t scant the disturbing, even monstrous, aspects of his belief, which other biographers do by careful omission.

Then there is Protestants: The Faith that Made the Modern World by Alec Ryrie, a professor at Durham University and a licensed lay preacher in the Church of England, who declares that understanding modernity requires understanding the history of Protestant Christianity, as he speedily marches from Luther and John Calvin and Henry VIII, through the English Civil War, witch burnings, the Christian promulgation and the Christian abolition of black slavery, Biblical criticism and the rise of liberal theology, churchly heroism and dishonor under the Third Reich, apartheid, the prosperity gospel in South Korea, the ascendancy of the American Religious Right and the decline of the American religious Left, and Pentecostalist speaking in tongues and miraculous healing. Protestantism, he writes, “helped to seed a great deal that we now think of as purely secular: rationalism, capitalism, Communism, democracy, political liberalism, feminism, pluralism. Even some forms of atheism have Protestant fingerprints all over them.” No Luther, no modern life, the adage seems to run—though Luther would have abhorred the unforeseen consequences of his hot spiritual convulsion.

Museums too have made beautiful contributions to the celebration, and sumptuously produced exhibition catalogues are among the most important books of the Luther year. For example, Martin Luther: Treasures of the Reformation depicts the objects lent by a host of German institutions for display at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, and the Pitts Theology Library in Atlanta. The 405 treasures include Luther-era hymnals, broadsides, theological tracts, Bibles (in Luther’s own classic translation), medals, engravings, etchings, woodcuts, paintings (including a number of artworks by Albrecht Dürer and the Lucas Cranachs Elder and Younger, who were instrumental in propagating the new faith), and even such oddments from the curiosity shop as Luther’s beer mug. Each object is aptly described, placed in context, and accompanied by a bibliographic note; longer entries explain key theological concepts and historical events—the catalogue in sum provides a fine introduction to Luther and his age.

Changing Direction

Martin Luther (1483–1546) was born Martin Luder, the eldest son of a smelting master, a prosperous figure in the copper mining industry in the town of Mansfeld. Hans Luder wanted his son to be more prosperous still, and thought his becoming a lawyer would be a sure road to wealth. In preparation for the law, Luther took a Master of Arts degree at the University of Erfurt, the oldest chartered German university, where humanist resurrection of ancient philosophy and literature flourished; the eager student learned the importance of recovering the antique sources and thereby circumventing the received wisdom, or blather, of the commentators. The method of direct engagement with the text would serve him well as he pursued his fevered scrutiny of Scripture.

Young Luther looked to be well on his way to fulfilling his father’s ambition for him, but a literal bolt from above changed the direction of his life. As he was walking home to Mansfeld from Erfurt, a summer thunderstorm burst upon him; such storms were thought to be the devil’s work or the result of witchcraft, and the frightened wayfarer invoked the power of Saint Anne, patron saint of miners, to save him from this heavenly fury. He was scared enough that he promised to become a monk if the saint’s intercession spared his life. Made in circumstances of mortal peril, such promises are commonly forgotten when the danger is safely past, but Luther did not forget, and he proved as good as his word. In July 1505 he entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt. His father was not pleased; at once headstrong and weak-minded, the young man was throwing his life away.

He set about becoming the best monk there was, a paragon of holiness. To his dismay—and horror—he found that he could never be as holy as he wanted to be. When he was celebrating his first Mass in 1507, his unworthiness so bedeviled him at the consecration of the Host that he was about to run away from the altar; his superior saw his panic and stopped him. Hans Luder was attending the Mass, and he made a munificent donation to the monastery in honor of the occasion. At the feast after Mass, however, when Luther asked his father before the assembled monks if he now approved of his son’s vocation, Hans reminded him of the commandment to honor one’s father and mother, and suggested that an evil spirit might have answered Luther’s prayer in the storm.

Perhaps an evil spirit moved Luder to speak this way to his troubled son. In the famous psychoanalytic study Young Man Luther (1958), Erik Erikson cites a letter that Luther wrote to his father about the contretemps more than a decade later, when he was famous, saying, “I, secure in my justice, listened to you as a human being and felt deep contempt for you; yet belittle your word in my soul, I could not.” The reasonable response to such paternal malice butted up against the chill spiritual fear that his father was right: his entire life was corrupt at the root. It is hard to be purely reasonable when one confronts an indomitable and implacable father. Even if one is disinclined to subscribe to Erikson’s whole Freudian rigmarole—Heinz Schilling disposes of it abruptly, while Lyndal Roper is cautious in her approbation—it is clear that Luther’s fear of his father’s anger figured significantly in his Anfechtungen—his temptations, travails, and tribulations—as he struggled toward an understanding of God, not as a merciless judge but as an all-forgiving redeemer.

Man of Sorrows

An all-forgiving redeemer of unforgivable human depravity: for Luther searched in the depths of his soul for some trace of saving goodness and found none. Living the monastic life of celibacy, poverty, and obedience, the most virtuous and sacred life available, simply was not good enough; not good at all. He confessed his sins every day, once spending six hours reciting his abominable transgressions, which in fact were trivial. His father-confessor, Johannes Staupitz, told him he could not understand this obsessive brooding over faults too slight to take seriously. The self-loathing would not abate.

Even worse, it was not only himself he hated. “I was myself more than once driven to the very abyss of despair so that I wished I had never been created. Love God? I hated him!” It is in Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (1950) by Roland H. Bainton, the still invaluable master scholar of an earlier generation, that one finds this hair-raising admission of Luther’s, and another to the same effect. Roper as well cites similar appalling testimony to the hero’s despondent rage against the Creator: “I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners.” One must reckon with the savagery of Luther’s fury against the God who made him—and made him such a miserable creature—if one is truly to understand the spiritual mire in which his religious innovation was conceived.

For in Luther’s eyes his misery was God’s doing, God’s inexorable will that he suffer so intensely, without hope of pulling himself out of the swamp bottom by his own strenuous efforts. God must have hated him even more, he thought, than he hated God. Honoring his monastic vows faithfully, relentlessly—prayer, fasting, vigils, cleaning latrines—did not help. Good works were useless. He tried to save himself and inevitably failed. He was unregenerate through no fault of his own and yet God made him pay.

Is it not against all natural reason that God out of his mere whim deserts men, hardens them, damns them, as if he delighted in sins and in such torments of the wretched for eternity, he who is said to be of such mercy and goodness? This appears iniquitous, cruel, and intolerable in God, by which very many have been offended in all ages. And who would not be?

Surely such unconscionable behavior on God’s part must be “against all natural reason,” as Luther wails in his Table Talk, the record of his pronouncements among friends and acolytes later in his life—but then that is the fatal shortcoming of all natural reason. Reason is “the whore,” he would repeatedly insist. God’s unreasonable iniquitous intolerable cruelty is the Almighty’s stroke of genius.

Luther would read and think his way out of his torturous predicament. Staupitz, seeing his protégé’s formidable intellect in distress, sent him to the University of Wittenberg to study theology and philosophy. Luther took his doctorate in 1512 and became professor of the Bible there, a position he would hold the rest of his life. Bainton calls Luther’s lectures on the Psalms, Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, and his Epistle to the Galatians, given from 1513 to 1517, “the Damascus road.” Luther would later refine and fortify the insights he had then in his wrestling with the texts, but the essentials were there already. Reading and writing were the instruments of salvation.

Psalm 22 anticipated the desolation of Christ on the Cross, who like the Psalmist cried out against the Father: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” The Savior in his Passion had known the same sense of abandonment that tormented Luther, and this brutal loneliness was more painful than the barbarities inflicted upon his body. As Bainton writes, “Christ too had Anfechtungen…. Christ had suffered what Luther suffered, or rather Luther was finding himself in what Christ had suffered, even as Albrecht Dürer painted himself as the Man of Sorrows.” That a man such as Luther should rail against God’s heartlessness was easy enough to understand: he was a wretched miscreant. Christ, however, was perfect in all his parts. How could he be reduced to flailing desperation? Bainton elucidates: “The only answer must be that Christ took on himself the iniquity of us all. He who was without sin for our sakes became sin and so identified himself with us as to participate in our alienation.” Luther had previously thought of Christ as he had seen him in a painting: sitting on a rainbow, majestic and unapproachable, dealing hard justice to reprobate mankind. Now Luther saw that Christ had experienced, not only the direst physical agonies of mortality, but more important the worst psychic depredations; and as a result his judgment was irradiated with pity and mercy.

Lighting the Pyre

But Luther was still an angry man. In September 1517 his assault on Catholic doctrine began in earnest, as he wrote a set of 97 theses, “in many ways more radical and shocking than the [later] Ninety-Five Theses,” Roper judges, attacking scholastic theology based on Aristotle. A student of Luther’s ably defended these theses in a public disputation. Attacking John Duns Scotus and William of Ockham by name, Luther proclaimed that “No one can become a theologian unless he becomes one without Aristotle.” Against Aristotle he pitted Saint Augustine, and declared in an Augustinian lament, “The truth therefore is that man, made from a bad tree, can do nothing but want and do evil.” This conviction of humanity’s demonic blackheartedness would be the sine qua non of his theology. Sin and suffering for your sinfulness are de rigueur; you have to sweat blood in anguish at your own corruption before you can hope to be saved.

Good works counted for nothing, Luther insisted, and indulgences—Church-approved penances for the remission of the temporal punishment due to sin—represented churchly good works of supposedly miraculous efficacy. It did not help, of course, that by the late Middle Ages indulgences had become widely abused and commercialized. In Alec Ryrie’s words, indulgences were little more than “documents in which the church promised to bestow God’s grace in recognition of a charitable gift.” Faith, hope, and charity were disgraced in a scandalous tangle.

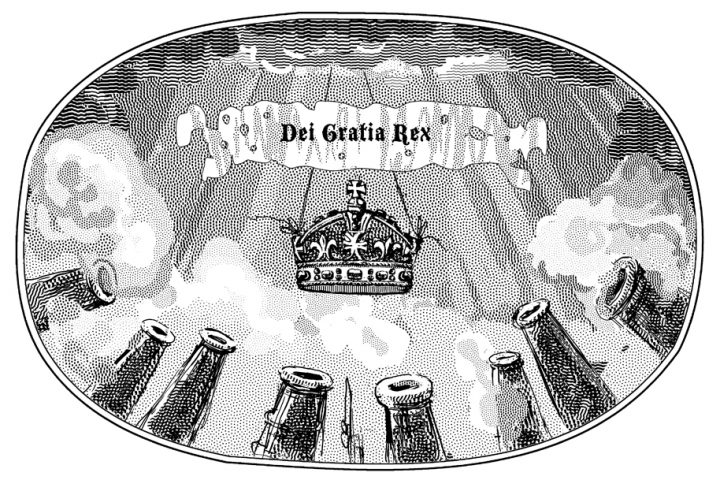

The whole business—and it was a lucrative business—showed the Church at its most presumptuous and grasping. In part to pay for the construction and decoration of the new Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the showpiece of Renaissance popes, Pope Leo X was selling exemptions from purgatorial fire for the living and for the purchaser’s dead loved ones—and if the payment was large enough, arranging an express route to heaven. The sacrament of penance had become derisory. The first of the famous 95 Theses posted at the close of October reads, “When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said ‘Repent,’ He called for the entire life of believers to be one of penitence.” The final one says, “And let [Christians] thus be more confident of entering heaven through many tribulations rather than through a false assurance of peace.” Indulgences were a scam, Luther argued, and the Church was selling sinners an entirely bogus ticket to paradise, which God would refuse to honor. The pope was damning his credulous flock for ready cash.

The 95 Theses against indulgences did not prompt immediate disputation, and perhaps, unlike other academic disquisitions, they were not intended to. They were printed, soon were famous and infamous throughout Germany, and traveled even more widely—in March 1518 the theologian Erasmus sent them from Rotterdam to Thomas More in England. In that month, too, students burned the defense of indulgences by the Dominican friar Johannes Tetzel, the pope’s prized salesman, in Wittenberg’s market square. Public book burnings would become a regular feature of Reformation contentiousness, and it was the Luther camp that first lit the pyre. Tetzel for his part predicted that Luther himself would burn for heresy, and fear of fire would pursue the bold innovator, though he professed to regard the threat of immolation as the honor of sacred martyrdom.

The theology of “many necessary tribulations” was being elaborated as Luther faced the outraged authorities. Several biographers highlight the critical antithesis Luther drew between the theological celebration of divine might and magnificence, on the one hand, and lower-case men of sorrows’ taking part in the unspeakable suffering of the Word made flesh, on the other. In his 40 Theses for the Heidelberg Disputation, Luther wrote in April 1518, “A theologian of glory calls evil good and good evil. A theologian of the Cross calls the thing what it actually is.” God brings men to their knees in unrelieved abjection, requiring that they touch the nadir of despair at their blighted awfulness and the unbridgeable distance from him, but then he relieves their misery by unfolding the grace of passive righteousness, the gift that Christ’s acquired sinfulness bestows upon forlorn and strictly undeserving humanity. The only road to heaven starts in excruciation.

Eleutherios

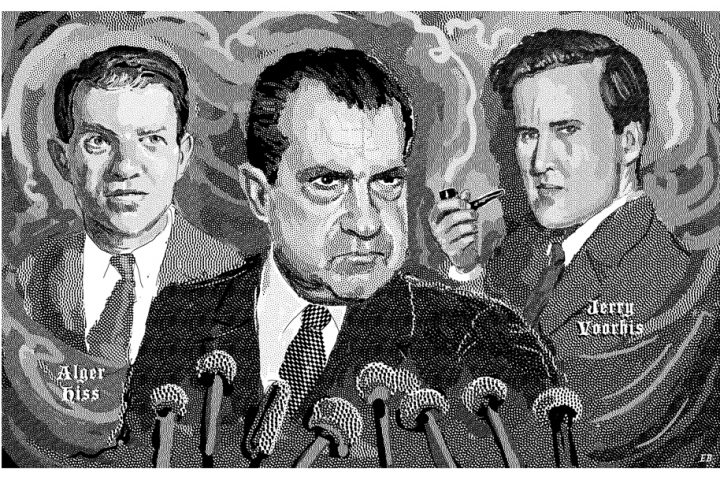

Luther confronted the hard trials of his developing faith as a new man. Like Saul becoming Paul, Fr. Martin Luder renamed himself Eleutherios, the free one—as Schilling states, “the one who has been liberated and, at the same time, the one who would liberate.” And in less sonorous German, Eleutherios became Luther. Called to defend his Theses three times in 1518 and 1519, he faced down the opposition of the Augustinian Chapter General in Heidelberg, the papal legate Cardinal Thomas Cajetan in Augsburg, and the very loud and angry professor of theology and canon law Johannes Eck in Leipzig.

By the time of the Leipzig Disputation, Schilling declares, “indulgences had been replaced by a far more hotly disputed issue—ecclesiology, doctrine about the church and most concretely the papal primacy claimed by Rome.” While Eck cited Scripture profusely on the papacy’s divine warrant, Luther invoked Church history to contend that the Throne of Peter—the pope’s teaching authority—rested strictly on human law. Such lèse-majesté was anathema. The distinguished academics judging the disputation found for Eck. The Causa Luther, as the Church called it, or the Luther Affair, would be decided along two divergent tracks: in Schelling’s words, “the official route, laid out by the church, led to a guilty verdict and excommunication; the second route, paved by the media and public opinion, saw the contentious issues submitted to each Christian, who would judge freely according to his or her abilities.”

The 1520 papal bull Exsurge, Domine, or Arise, O Lord, threatened excommunication if Luther did not recant. The former monk wrote back defiance, in hot-blooded essays called On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church and On the Freedom of a Christian. “A Christian is a perfectly free lord of all, subject to none. A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all.” Excited Germans saw the Roman grip loosening and a new dispensation emerging. Luther called the pope the “true and incarnate Antichrist,” a recurrent theme in the writings that provided the subject of numerous foul cartoons. The Church consigned Luther’s books to the flames. In response he burned the canon law and the papal bull: “As you have destroyed the truth of God, today the Lord destroys you. Get into the fire.”

Charles V, the 21-year-old Holy Roman Emperor-elect, demanded Luther appear at the Diet of Worms in April 1521 to declare whether or not he recanted. There Luther made the pronouncement of indomitable will and rectitude that became the watchword of Lutheranism:

I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. I cannot do otherwise, here I stand, may God help me. Amen.

Charles V, moved by personal faith and political necessity—his ambition of universal empire, never to be realized, rested on a unified Catholic Church—vehemently censured Luther and issued an imperial ban. He was now an outlaw, without legal protection from any of the powers arraying themselves against him. Although Luther had been assured safe passage home from Worms, his protector Friedrich the Wise, Elector of Saxony, mistrusted that promise, staged Luther’s abduction on the road, and secreted him in the Wartburg, Friedrich’s fortress outside Eisenach. Albrecht Dürer, hearing rumors that Luther had really been ambushed and killed, lamented in his diary:

Oh God in heaven, that we should lose this man who has written more clearly than ever any other, to whom you have given such an evangelical spirit, we ask you, oh heavenly father, to give again your holy spirit to another who will again gather together your holy Christian church.

In fact Luther was writing prolifically while in hiding, beginning his translation of the New Testament, as canonical in German as the King James Version (KJV) is in English. The translation “was not without its tendentious features,” Lyndal Roper observes. Luther’s rendering of Romans 3:28 reads, “So we now maintain, that man becomes justified without the work of the Law, through faith alone.” The word “alone” does not appear in the Greek original (or in the KJV); the telling emendation emphasizes the crux of Luther’s belief, in sola fide, sola gratia, sola Scriptura: by faith alone, grace alone, Scripture alone does a genuine Christian recognize the truth and find salvation. If the Word needs a nudge here and there to get the point across, so be it: in Scripture alone as Luther understood it the truth resides, and he had his favorite books, Romans preeminent among them, and others that he rejected as unsound, such as the Epistle of James, which attributes an intolerable significance to justification by works. (Luther attempted to have James along with the Epistles of Jude and Hebrews and the Book of Revelation removed from his canon, until cooler heads prevailed.)

Meanwhile, enthusiasts prone to excess and even violence were co-opting Luther’s revolution. His academic colleague Andreas Karlstadt was preaching Gelassenheit—in Roper’s words, “the meditative ‘letting go’ of human attachments in order to allow God to enter, which reveals the extent of his debt to medieval mysticism.” Luther found repugnant Karlstadt’s contempt for the human body, which sounded like unacceptable monkishness. His iconoclasm—all who honored images were “whores and adulterers” in his eyes—also met with Luther’s disfavor. Karlstadt was introducing reforms in Wittenberg that would eventually gain Luther’s approval: offering communicants wine as well as the traditional bread in defiance of Catholic practice, introducing German into the liturgy, abolishing begging and providing for the poor with community funds. But in 1522 Luther saw Karlstadt as a usurper and the populace as spiritually unready for such innovations. And he was certainly right about the populace: as in Wittenberg so throughout the empire, the evangelicals were running amok, “interrupting sermons, destroying altarpieces, tearing up Mass books, urinating in chalices, or mocking the clergy,” as Roper notes. For too many the Christian’s new freedom was berserker license. So on returning to Wittenberg, Luther sided with the secular authorities to rein in Karlstadt, whom he accused of literal devilment, and to brake the momentum of change.

Relentless Struggle

Then, as Roper writes, “in the autumn of 1524, the biggest social uprising in the German lands before the era of the French Revolution began.” The Peasants’ War’s masterminds, a furrier and a Lutheran preacher, drew up their demands in the Twelve Articles, which deployed Reformation shibboleths such as freedom, Christ alone, the unique authority of Scripture, and each community’s right to elect its own pastor, in support of social and economic reform. Luther in a rage blamed the rebellion on Karlstadt and Thomas Müntzer, another renegade prophet, trying to bring on the Last Days with a sword. Luther’s pamphlet Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants called on the princes to extinguish the revolt with extreme prejudice:

Let whoever can stab, smite, slay. If you die in doing it, good for you! A more blessed death can never be yours, for you die while obeying the divine word and commandment in Romans 13, and in loving service of your neighbor, whom you are rescuing from the bonds of hell and of the devil.

In the war’s final battle, 5,000 peasant soldiers fell, and the captured Müntzer was beheaded. In his Open Letter on the Harsh Book against the Peasants, Luther defended his bloody-minded wrath with the doctrine of the “two kingdoms”: in Schilling’s words,

the spiritual kingdom of God, in which compassion and mercy reign, and the kingdom of earth, in which the anger of God and the relentless struggle against evil are sovereign. The tool to be employed in the kingdom on earth by the authorities responsible for order and law is, he continued, “not a wreath of roses or a flower of love, but a naked sword.”

This distinction between kingdoms would be “the foundation of Protestant political theory,” Alec Ryrie avers. Radical Protestants such as Anabaptists—believers in adult baptism—observed the distinction with consummate fervor, refusing to swear civic oaths or fight in armies: withdrawal from the kingdom of sin was the imperative of the kingdom of heaven. Luther for his part would follow his Wittenberg colleague Philip Melanchthon in admitting the princes’ responsibility to oversee the well-being of the new church. As Ryrie writes, Luther asserted that the prince had a duty

to suppress Anabaptists and other “fanatics.” However, he denied that this was religious persecution. It was simply the suppression of rebellion or the punishment of blasphemy, which was legitimate, he argued tendentiously, because openly defying God was a denial of natural justice.

To defy Luther was to deny God. He was extremely protective of the integrity of his religious vision, and he was a very determined and violent hater. The poison in Luther’s screeds and Lucas Cranach the Elder’s cartoons—Cranach was Luther’s friend and chief pictorial propagandist—is at least as morally lethal to its own dispensers as the current venom of Islamist fanatics. In Cranach’s The Origins of the Monks, reproduced in Roper’s book, a pile of fat tonsured friars mounts beneath a gallows, where a devil squats at stool evacuating them. In the companion piece The Origins of the Antichrist, a pair of devils attends to the pope’s fat corpse, white as a maggot and wearing only its tiara, while two other devils grind a tubful of monks with the papal key to the kingdom as with a mortar and pestle.

Luther never tired of spurting scurrilous abuse at the Catholic Church or at Protestant splinter denominations that departed from his new orthodoxy; and he had choice words for Muslims, calling the Koran an “accursed, shameful, desperate book” laced with “secret poison.” His published loathing for the Jews exceeds that for any other unbelievers.

In The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), William James writes of “the sick soul” and its needs that a faith such as Luther’s fills, as the sufferer feels “the grisly blood-freezing heart-palsying sensation of [evil] close upon one.” There is the intellectual faith “that Christ has genuinely done his work,” but there is also the “immediate and intuitive” faith “that I, this individual I, just as I stand, without one plea, etc., am saved now and forever.” This is the most eloquent testimony I know to the appeal of Luther’s faith.

But was this indeed the principal appeal that Luther had for the men and women of his time and that produced the Reformation? Craig Harline in A World Ablaze comes out and says what the other biographers carefully edge their way around: that it was not the theological insight of justification by faith that won the masses, but the promise of freedom from various hated oppressions. For some princes the freedom of a Christian meant “being free from Rome, and taking charge of the church (and its lands) within their territories.” For most peasants it meant

freedom from their local landlords who were trying to bring back old obligations that peasants thought they were done with, and freedom to choose their own pastor or preacher, and freedom to hear the Mass in German instead of Latin, and freedom to pay a lighter tithe, and freedom to hunt venison and fowl in the woods and to fish in streams, and freedom to cut wood and use meadows when they needed to, and freedom to have fewer rules, and, yes, freedom to send less money to Rome too.

And Luther freed the clergy and religious from the burden of celibacy and poverty: the monasteries emptied as their sometime inmates were free to marry as Lutheran ministers, and Luther himself married and fathered six children by a nun who had left the convent.

Faith and Reason

There is another freedom as well, which Luther, like John Calvin after him, denies the true believer, and paradoxically liberates him from: free will, freedom of choice. In 1525 Erasmus and Luther fired off an exchange of disquisitions, the Catholic humanist writing his Diatribe Concerning Free Choice, the Protestant prophet retorting with a prolonged sneer in On the Bondage of the Will. Erasmus opens with an argument from common sense: the Lutheran doctrine of necessity and predestination seems not a spiritual liberation but a punishment. “Who will be able to bring himself to love God with all his heart when he created hell seething with eternal torments in order to punish his own misdeeds in his victims as though he took delight in human torments?” Here is the unintended consequence of justification by faith alone: the belief might relieve Luther’s terrors but will multiply them for most others.

As this argument relies on mere natural reason, Erasmus buttresses his case for free will with Scriptural citations, including a number from Luther’s hero, Saint Paul. Luther for his part contends that “the immutability of God’s will” and “the immutability of His foreknowledge” are indivisible: God knows the future so the future is as ironclad certain as the past. Luther would not want to have free will even if he could, he writes: that is too perilous for him, as he knows he cannot be good enough to save his soul. What he wants is an incontrovertible promise of salvation, which he finds only in passive righteousness, not in choosing virtue. In the end the philosophically insoluble question is of interest chiefly for the psychology of belief: most every human being knows the experience of free will, yet neither disputant begins with that, but rather from the attributes of the Christian God, which are ultimately a matter of faith, and both leap into the arms of Scripture. Their reasoning has faith as its foundation.

Luther was not guilty of murder, or adultery, or by his own account even lust in his heart; he was not an atheist or an idolater, a rogue or a liar, a bandit or a second-story man. His profuse upsurge of sinfulness in confession made his wise father-confessor scoff at the paltriness of it all. If Luther had been a normal, reasonable man, his peccadilloes would have proved inconsequential; instead, they moved the world. Luther’s hatred of himself and of God, and his release from torment through a novel interpretation of the divine Word, provide rich matter for the psychologist, but can hardly be taken as the definitive source of truth about man and God.

And yet multitudes flocked to the new religion as though it were absolute truth. It did fulfill many needs and desires. In the stampede beauties were crushed. Friedrich Nietzsche lamented, “The Germans have cheated Europe out of the last great cultural harvest which Europe could still have brought home—that of the Renaissance.” Reformation and Renaissance continue their struggle for men’s souls, on a battleground extending from this world to the next.