Books Reviewed

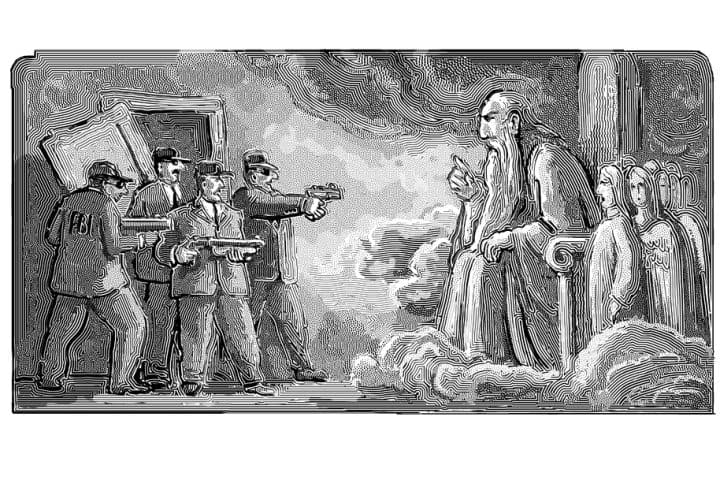

Existing for two millennia, Christianity has survived Roman persecution, Islamic competition, and profound schism. Whether it can survive modern democracy remains to be seen, however. In recent centuries it has been tolerated almost to death, and so diluted to accommodate modern scientific discoveries or the promise of human liberation that little revelation, doctrine, or ritual may be left to sustain the faithful.

The latest twist in modern democracy’s approach to Christianity is the so-called public reason test, devised by the late Harvard professor of philosophy John Rawls. Treated by many of Rawls’s followers as self-evidently true, public reason allows believers in “comprehensive doctrines,” like Christianity, to enter the political sphere if they “translate” their advocacy into terms acceptable to other citizens. Thus, in theory, believers could hold private religious beliefs, but would have to put those beliefs on a secular basis when entering the political arena. One may support universal health care privately because one thinks it required by Christian charity; as a matter of public reason, one must defend this view in terms of saving costs or equal citizenship so non-believers could endorse it.

* * *

Giorgi Areshidze’s Democratic Religion from Locke to Obama treats Rawls’s approach as historically naïve, as it underestimates the power of comprehensive doctrines to insist on their own worldview. A Claremont McKenna College political scientist, Areshidze dissects the public reason doctrine by examining the philosophers and statesmen who helped make Christianity safe for modern democracy in the first place. John Locke, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Luther King, Jr., articulated an earlier “democratic transformation of religion” that Rawls’s doctrine now challenges.

The Christianity with which Locke had to contend, according to Areshidze, treated persecution and doctrinal intolerance as natural, necessary expressions of Christian love and charity. For example, Anglican cleric Jonas Proast, one of Locke’s interlocutors in defining Christianity, feared that a public teaching of toleration would foster religious skepticism and doubt. Proast thought Locke’s teaching on toleration would lead to a dangerous pluralism that would unmoor the religious conscience from true doctrines, forcing believers to rely on their private faculties to pose and answer the biggest questions. So successful was Locke’s redefinition that, three centuries later, we cannot comprehend the Christianity that defended intolerance because it was loving and salvific. Locke, Areshidze shows, reshaped Christianity to minimize religious dogmas and emphasize good works and charity. This new Christianity would renounce shaping consciences through any non-consensual means, putting matters of the soul completely beyond civil government’s ambit.

Lincoln continued this process. Against pro-slavery theologians, Lincoln’s “active and rationalist reinterpretation of the Bible” grafted onto “the revealed text the doctrine of an individual’s right to property to the fruits of his labor.” This new Christianity shaped the nation’s religious consciousness about slavery in accord with the demands of natural justice.

Martin Luther King’s efforts in America and elsewhere to re-interpret Christianity opposed quiescent, otherworldly Christians who counseled obedience to the laws as a matter of conscience. They liked to quote Romans 13 in support. The “powers that be are ordained of God,” according to scripture. “Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God.” This old submissiveness, King warned, robbed Christians of the opportunity to make prophetic witness and reinforce their religion’s health and vigor by affirming the truth that “God has created all human beings with equal rights and equal dignity.” King admitted that civil disobedience required a “departure from the original biblical message,” which he explained away as a reflection of a very different “historical setting.” Equipped with the higher criticism and progressive revelation of modern times, King possessed the “necessary tools” for “social transformation” in the service of greater equality and liberation, Areshidze claims. The passing needs of politics drive his theological interpretation and Christian engagement.

* * *

Areshidze extends this story of the democratic reconstruction of the Christian religion to the present day. Barack Obama’s contribution to American Christianity, argues the author, is his attempt to combine faith with doubt, diluting “fanaticism” to leave room for pragmatic deliberations about what works. Yet fanaticism has its uses. Obama worries that true believers such as Lincoln have made history, depriving him of “the certainty of uncertainty.” Obama would invite faith into the public square when it supports “the need to battle cruelty in all its forms” and when it values “love and charity, humility and grace”—in other words, when it advances liberal politics as he understands them. At other times, such as when they insist life begins at conception, Obama sees Christians tracing beliefs to obscure Biblical passages and culture-bound doctrines that (echoing Rawls’s “public reason” test) have no place in a decent society. Obama is “absolutely sure” about some parts of the Bible but not others. He seems certain that Islam is a religion of peace, which means that efforts to co-opt Islam for purposes of terrorism are unwarranted and spurious, almost as much as arguments are that hold Islam responsible for the terrorism committed in its name.

Locke, Lincoln, King, and Obama flexibly reinterpret Christianity, insinuating their philosophical or ideological teachings into a pre-existing Christian framework. All liberalize and modernize Christianity by employing variants of the historical-critical method. Obama’s approach seems to be more narrowly partisan than Lincoln’s, but is it just as legitimate? It’s not clear if Areshidze draws a line between Lincoln and Obama, or on what grounds he might.

If Areshidize stops his analysis short, he also undersells its implications. Democratic Religion shows that the incompatibility between modern democracy and Christianity is deeper than even the advocates of public reason had thought. Only a bridle distinct from democracy could tame what Alexis de Tocqueville called its “savage instincts.” But as democracy radicalizes it shakes off all bridles. Democracy directs our attention away from the eternal to the here and now, and erodes the authority on which any religious faith must rest.

* * *

Areshidze canvasses the problem of an excessively domesticated Christianity in his chapter on Jürgen Habermas and Tocqueville. Habermas, a Marxist of the Frankfurt School variety, recognizes Christianity’s nondemocratic nature and its resulting political value. The “pre-political” headwaters that created and sustain modern liberal democracy, he specifies, are Christians’ beliefs in equality and responsibility, civic and familial notions modern secular thought can neither recreate nor sustain. Habermas would have democracy learn from Christianity but, like the others, he keeps democracy in charge.

Only Tocqueville, according to Areshidze, genuinely values Christianity’s otherness. Tocqueville sees that in the modern West religious practices, forms, doctrines, and morality tend to become democratized and homogenized. Faith becomes less exclusive, morality becomes more permissive, and formal religious ceremonies wither. In Mary Eberstadt’s recent formulation, Protestants secularize, and Catholics become Protestants. But Tocqueville discerned that a hardier, more stubborn Catholicism could stand outside this democratic movement and tutor democracy against its main deficiencies. “Religion must either embrace toleration by declaring itself indifferent to theology or be deemed an intolerant faith,” Areshidze writes. Only Catholicism, as a matter of long historical practice, dares stand apart from and even against the democratic regime, undaunted by the prospect of being branded intolerant.

* * *

Democratic Religion from Locke to Obama concludes by discussing, too briefly, an inevitable trade-off. A robust, non-democratic religion can temper individualism, ground community, and provide prophetic witness to injustices. But the more flexible the religion, theologically and morally, the less robust, tempering, and prophetic it will be. To reckon with this trade-off is to be disabused of the comforting illusion that we can enjoy the best of both worlds without having to choose. Those who disdain inflexible religion, which is nearly everyone in modern democracies, should be candid about what’s lost when religion becomes too flexible.

The tendency to subordinate religion to democracy, however, may not prove irresistible. The soul always presses against the barbed wire of a particular political community, to modify Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s formulation. Christianity exists in a conventional setting that shapes its practice, so modern democracy may make Christianity an excessively civil religion. Yet religious passions and instincts—the thirst for righteousness, hope for a better world, and shame and sorrow over the imperfections of this one—are sown in human nature, too. Areshidze’s fine study shows that a civil religion that points beyond itself to speak to these instincts is a great desideratum for any political community, especially a democratic one.