Books Reviewed

Parents have always fretted about what to read to their children, and experts have always been ready with advice. In their educational writings, John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau together mentioned only three books worthy of a child’s mind. Locke recommended Aesop’s Fables and Reynard the Fox, while in Emile the tutor Jean Jacques offered his charge only Robinson Crusoe. How times have changed. The new 2,471-page, lap-crushing Norton Anthology of Children’s Literature includes several hundred entries, both old and new. But far from representing an efflorescence in childhood literature, this volume marks the genre’s sad end.

The editors of the anthology acknowledge in passing their debt to Locke and Rousseau—who in a sense created our modern understanding of childhood, permanently influencing all subsequent children’s literature. The editors, however, wish to promote a revolution of their own: a new, more candid, and frankly, more nihilistic corpus. Despite heralding children’s literature as “life-enhancing” and “life-changing,” the Norton editors aim in fact to dampen children’s enchantment with the world, forcing them to acquiesce to the grim realities and multicultural obsessions of contemporary adults.

Of course, this could be because the book was never meant to be read by or to children. The editors, all scholars of some sort, with backgrounds in literature, education, and history, describe their handiwork as a “more scholarly” anthology, one that incorporates “profound changes” from earlier collections, and is intended mainly for the college student. Whereas editors of previous anthologies “favored classic authors” and “canonical texts,” with a minimum of reader notes and introductions, the Norton edition aims to be more inclusive of “emergent” literature. As the editors state, “Our critical perspectives, like those of scholars in other literary fields, have been greatly influenced by the research and criticism rooted in the feminist and multicultural movements.” Their real hope is “to revolutionize the undergraduate curriculum.”

The anthology is divided into 19 chapters covering various divisions within children’s literature (“Chapbooks,” “Primers and Readers,” “Fairy Tales,” “Classical Myths,” “Legends,” “Fantasy,” “Verse,” “Picture Books,” “Books of Instruction,” etc.). Each chapter begins with a long introduction in which the editors supply an overview of the genre’s historical trajectory, and discuss its defining works, including many hitherto unknown. The chapters contain at least one “core” text in full, along with shorter or excerpted “satellite” texts. Each text is preceded by laborious reader notes, many of which are longer than the text itself. There is also a 32-page section of illustrations from some of the great picture books, including Beatrix Potter’s Tales from Peter Rabbit, Jean de Brunhoff’s The Story of Babar the Little Elephant, Marjorie Flack’s Angus the Duck, Ezra Jack Keats’s Snowy Day, and Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are.

The editors included some genuine classics, to be sure, some excerpted and some in full, like The New England Primer, A Child’s Garden of Verses, Peter Pan, Ramona and her Father, chapbook versions of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Defoe’s Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, and the poetry of Charles Causley and Robert Graves, to name just a few. One could certainly quibble with the editors about omitted texts. Why no poetry from Emily Dickinson, for instance, or any meaningful mention of Shakespeare, whose plays were re-written into children’s story form by Charles and Mary Lamb? But such quibbling is to miss the larger problem with this volume. It is not so much an anthology as a postmodernist manifesto.

* * *

As the editors declare in the preface, “In our choice of texts and in our introductions, we have paid close attention to…perceptions of race, class, and gender, among other topics, in shaping children’s literature and childhood itself.” Practically every text and every author (save for the “emergent”) is subjected to a wicked scolding from the editors for its racism, sexism, and elitism. Forget about ogres, witches, monsters, and evil stepmoms; today’s villains are gender stereotypes, white males, the middle class, and the traditional family. Retrograde literature must therefore be replaced by a new one, one that is, as it were, beyond good and evil: “In our postmodern age, in which absolute judgments of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ are no longer easily made, the distinction between heroes and villains is often blurred.”

The editors herald this as a great advance, one they wish to promote by burying the stories under a ton of commentary. To read a children’s story out of context, say the editors, is so passé (so childish?): “Discourses such as reader-response theory, poststructuralism, semiotics, feminist theory, and postcolonial theory have proven to be valuable in analyzing children’s books.” Thus the editors introduce Fun with Dick and Jane by noting that the “world of Dick and Jane was the idealized image of white, middle-class America.” The introduction to the chapter on “Legends,” which includes The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood and King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, warns that “history has generally been written by the victors and the elites, who tend to view those like themselves—white males, for the most part—as heroes.”

In the chapter on “Classical Myths,” the editors ponder whether myths are being “kept alive” “by unreflective adults.” After all, myths are prone to “strong gender stereotyping—females are passive, males are active…. The protagonists are devoted to a ruthless elimination of the ‘other’ and to a savagery that is scarcely tolerated” in other children’s literature. The genre of domestic fiction—which includes works like Little Women, Anne of Green Gables, and The Bobbsey Twins—”showcased white middle- or upper-class families.” But the editors are happy to report that “the genre has come to reflect ethnic, racial and class diversity.” Nor are they above offering advice to would-be authors: “still more change would be welcome here.”

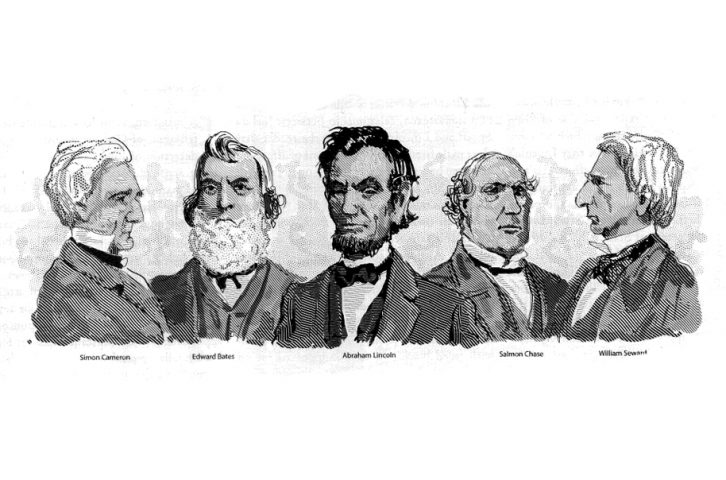

All this Sturm und Drang over children’s stories is hardly new. Ever since Socrates took on Homer by banning poets from the Just City, philosophers have well understood that, as Shelley put it, “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” But to understand how we got here, we need not go back so far. There have been three revolutions in modern children’s literature.

The first was instigated by John Locke. In founding a new political and intellectual order—a liberal, tolerant regime—he believed that reforming children’s education was of the utmost importance. Notably, he advised against reading Scripture to children, because, as he wrote in Some Thoughts Concerning Education, the Bible was ill-suited to a “Child’s capacity” and “very inconvenient for Children.” Locke’s aim was to take education from the hands of the clerisy, and to overcome its domineering and persecutory spirit.

Contrast Locke’s sensibility with that of a contemporaneous textbook. The God-fearing New England Primer (c. 1690), included by the Norton editors, drilled children in their ABCs thus:

A: In Adam’s Fall

We sinned all

B: Heaven to find

The Bible Mind

C: Christ crucify’d

For sinners dy’d

This was an education not simply in reading and writing, but in living and dying, one that did not condescend to the limited understandings of children. Locke rejected all this, mischievously suggesting that children learn their letters by playing dice. In the wake of Locke’s reformation, a more humanistic educational literature gradually blossomed. Unlike the somber New England Primer, the stories were secular, rational, and geared towards children. Though entertaining, these stories were meant to impart a moral message, to help children grow into responsible adults. In this sense at least, Locke still had something in common with the authors of the old New England Primer.

In the late 19th century, another revolution took place, this time marked by a wholesale shift away from moralizing. A new genre of children’s fantasy emerged, seeking only to entertain. One of its most prominent voices was Lewis Carroll. As the editors explain, his “mockery of instructional verse, rote learning, and moralizing school curricula helped move the genre from eighteenth-century concerns with the instruction and correction of children toward modern celebrations of play.” This era is known as the “golden age” of children’s literature—golden precisely because it celebrated the innocence and playfulness of childhood, and sought to free children from the grief and worry of adults. Carroll’s Crocodile, a parody, “seemed to license childhood playfulness, fantasy, laughter, and even idleness.” “The change was welcome,” add the editors.

Alas, golden ages never last, and children’s literature was no exception. The third and last great change occurred in the 1970s, when writers started to “push the boundaries” of material considered acceptable for children. According to the Norton editors, “In the wake of this revolution, writers for the young can deal with sex, violence, disease, and death—in particular because many believe that the innocence of childhood has been destroyed by the media and the commodification of childhood.”

* * *

Indeed, it’s hard nowadays to tell children’s literature from adult literature. As the editors correctly observe, this is partly because the lines between childhood and adulthood have themselves become blurred. Locke thought that the “tender” minds of children should be protected from the corruptions of the adult world—and yet these are now the genre’s warp and woof. “Children’s literature has also begun to resemble adult literature in subject matter,” write the editors, “using frank and provocative language to depict and discuss social problems such as homelessness, drug addiction, abuse, and terrorism and expanding the notion of family to include nontraditional families led by single parents, stepparents, and gay and lesbian parents.”

Thus the postmodern adult world, in all its vulgar glory, is visited upon our children. The editors enthusiastically endorse Jonathan Miller’s 1984 picture book The Facts of Life, which includes a “pop-up penis.” Apparently, alternative families provide especially good material for young readers today. After touting the groundbreaking work Heather Has Two Mommies, and chiding Focus on the Family and the Heritage Foundation for seeing it as a threat to “what they call traditional American values,” the editors assure us that “there are today no real taboos in domestic fiction for young adults, and few in books for the youngest readers. Family stories now tackle every painful issue imaginable.”

Indeed, they do. Fairy tales, which have always dealt with dysfunctional families, especially wicked stepmothers, now take on a hard modern edge by tackling perhaps the last taboo, incest. The Norton Anthology contains ten versions of Little Red Riding Hood, beginning with Charles Perrault’s classic and ending with Francesca Lia Block’s Wolf (1998). Block, unlike Perrault, isn’t satisfied with the sexual undertones and imagery of the original; her heroine is the victim of rape at the hands of her mother’s boyfriend (“he held me under the crush of his putrid skanky body”) whom she kills with a shotgun at her grandma’s house. The editors tell us that this “story shows how a young girl can take charge of her life, while at the same time exposing the sado-masochistic ties that exist in many dysfunctional families.”

Well, perhaps, but is this really a story for children? “Once upon a time” used to be a gateway to a land that was inviting precisely because it was timeless, like the stories it introduced and their ageless lessons about the human condition. But this invitation must now apparently read, “Once upon a time when women were powerless and exploited and white male hegemony ruled the world, and when the sky was dark….”

In a strange way, completely unappreciated by the anthology’s editors, we have returned to the pre-Lockean age of children’s literature. Locke wished to scrub stories clean of horrific images and premonitions of death—not because he was a naïf or a utopian, but because he believed it possible to build a more rational, humane world. The Norton editors break with him on this central issue. They do not believe in the possibility of a more rational world, or even, it would seem, in childhood itself. And so they have more in common with the New England Primer than they dare to admit. They, too, are obsessed with death and the apocalypse, only they don’t believe in redemption.