Books discussed in this essay:

Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist, by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

Charles Dickens: A Life, by Claire Tomalin

Conservatives today generally cringe when literary criticism turns into political debate—or hectoring, for the Left commands the discussion, with its obligatory reduction of great poems, plays, and novels to their unspeakable racist, sexist, and class-bound assumptions. When the conversation turns to Charles Dickens (1812-1870), however, politics implicit or explicit is unavoidable. As George Orwell declared, in the celebrated opening sentence of his 1939 essay "Charles Dickens," "Dickens is one of those writers who are well worth stealing." Orwell sets out to rescue Dickens from the clutches of Marxist bandits who would turn him into "a bloodthirsty revolutionary" and Catholic zealots who would canonize him quite against his will. Orwell's Dickens is sensible yet impassioned, endlessly fertile because transfixed by the joys and pains of humanity: "For you can only create if you can care." The closing sentence of the essay (also celebrated) presents Dickens as a sort of prototype for Orwell himself: "It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry—in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls." The contention for our souls never quits, and maybe Dickens, and the view of Dickens through the eyes of some of the contenders, can help show us, in the bicentenary year of the writer's birth, how to put our souls right.

Overflowing Invention

Admirers as different in temperament as George Santayana and G.K. Chesterton, the former as free an intelligence as the 20th century produced, the latter according to Orwell a "medievalist" who tried to turn Dickens into one too, find Dickens's principal genius in a creative capacity as nearly god-like as a man can possess, but joined to the most human heart. In the essay "Dickens" in Soliloquies in England (1922), Santayana esteems Dickens for what many consider a fiction writer's ultimate accomplishment: creating "a fresh world, where the men and women differ from real people only in that they live in a literary medium, so that all ages and places may know them." Dickens creates with a free and generous hand, almost as nature did in bringing forth the human plenum from which he draws fictional life.

The most grotesque creatures of Dickens are not exaggerations or mockeries of something other than themselves; they arise because nature generates them, like toadstools; they exist because they can't help it, as we all do…. The sleepy fat boy in Pickwick looks foolish; but in himself he is no more foolish, nor less solidly self-justified, than a pumpkin lying on the ground.

Nature's freedom, and Dickens's, is every creature's necessity.

Yet a familiar morality does constrain Dickens's creative reach as it does not nature's. For while Santayana always holds that to invest nature with human tenderness, indeed with any human motives at all, is patent foolishness, Dickens's own feeling for the lowly and broken colors his entire life's work.

I do not know [wrote Santayana] whether it was Christian charity or naturalistic insight, or a mixture of both (for they are closely akin) that attracted Dickens particularly to the deformed, the half-witted, the abandoned, or those impeded or misunderstood by virtue of some singular inner consecration. The visible moral of these things, when brutal prejudice does not blind us to it, comes very near to true philosophy; one turn of the screw, one flash of reflection, and we have understood nature and human morality and the relation between them.

Human morality, Santayana subtly indicates, makes up for what nature lacks: sensitivity to suffering. Perhaps strictly by accident—Santayana suspects it might be so—nature endowed men with the ability to feel another's feeling; in democratic times, this fellow feeling most emphatically takes the form of compassion, of suffering with those you see suffer. Dickens certainly possessed one of the most compassionate democratic hearts ever.

Yet his was not a simple compassion. Santayana again:

Love of the good of others is something that shines in every page of Dickens with a truly celestial splendour. How entirely limpid is his sympathy with life—a sympathy uncontaminated by dogma or pedantry or snobbery or bias of any kind! How generous is this keen, light spirit, how pure this open heart! And yet, in spite of this extreme sensibility, not the least wobbling; no deviation from a just severity of judgment, from an uncompromising distinction between white and black.

Love of the good of others implies hatred of the evil that everyone suffers sooner or later, and some people all their lives long, whether from nature or society. Nevertheless, Dickens's spirit remained keen and light: for him, to be alive was above all a pleasure, even though for multitudes, whose plight he so deeply cared about, it was a brutal ordeal. His sympathy lay not just with life at its most awful, but with life in its uncanny fullness. And his fundamental sympathy with life did not mean he gave evildoers a pass; quite the contrary. He might have appeared to possess the makings of the sort of woolly liberal who tolerates most everything from everybody, and yet he could be a stern moralist. In short: a natural conservative, with the best liberal traits for good measure, not unlike Santayana himself.

A devout Christian who scorned both liberalism and conservatism, Chesterton rhapsodizes, in Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens (1911):

He has created, especially in this book of David Copperfield, he has created, creatures who cling to us and tyrannise over us, creatures whom we would not forget if we could, creatures whom we could not forget if we would, creatures who are more actual than the man who made them.

One may be inclined, especially if one is a conservative, to think of such burgeoning creativity as above mere politics. However, Chesterton recognizes that Dickens's art is not quite as disinterested as that:

It is not true to say that Dickens was a Socialist, but it is not absurd to say so. And it would be simply absurd to say it of any of the great Individualist novelists of the Victorian time. Dickens saw far enough ahead to know that the time was coming when the people would be imploring the State to save them from more freedom, as from some frightful foreign oppressor. He felt the society changing; and Thackeray never did.

Dickens may not have advocated a social program but he did work with a social purpose. His fiction inveighed against the worst ills of poverty and the insensibility of the prosperous. If Chesterton is right and Dickens was not a socialist, then he was a fiery Radical, or Liberal as he called himself later in life. As an artist, he could not be entirely a free spirit. The suffering of others weighed too heavily with him. He was bent on altering men's souls and thus their societies. But it was individual souls that had to change first.

In the crucial respect, Chesterton and Santayana agree on the springs of Dickens's creativity. Dickens can create as he does because he holds a fundamental belief about the world in which he was created: people are what they are, and that will never be otherwise. However cruel life might be reality cannot be gainsaid. This is a hard view to maintain. Perhaps the best thing for it under the circumstances is to be a novelist of overflowing invention. If one is fortunate enough to be uncommonly gifted in the fiction-writing line, he can find sustenance and joy in imitating nature or the deity and imagining a world distinctively his own. This aspect of Dickens's art and character can be called conservative in the whatever-is-is-right fashion. You do not get more conservative than that. But that is of course only half the story about Dickens; for no other great novelist enjoys such fame for demonstrating over and over again that so much of what is is wrong. The world's cruelty is intolerable for this Dickens, and with a full heart he cries that people must change or this suffering will never abate. You do not get more liberal than this.

What Was He After?

Chesterton and Santayana tend to approach Dickens's politics sidelong; it is not their chief concern. There are other important critics who are more directly political. Walter Bagehot's long 1858 essay "Charles Dickens" distinguishes between the symmetrical genius such as Plato or Chaucer, with an appreciation for order, proportion, and unity, and the unsymmetrical genius of a Dickens, whose "abstract understanding is so far inferior to his picturesque imagination as to give even to his best works the sense of jar and incompleteness, and to deprive them altogether of the crystalline finish which is characteristic of the clear and cultured understanding." To put it more pungently: Dickens cannot reason to save his life. "He is often troubled with the idea that he must reflect, and his reflections are perhaps the worst reading in the world. There is a sentimental confusion about them; we never find the consecutive precision of mature theory, or the cold distinctness of clear thought."

In Dickens at his worst what we find instead, Bagehot complains, is a jumble of wrong-headed theory and an overheated feeling that passes for serious thinking. It is Dickens's politics, especially in the later novels, that Bagehot really objects to, and most strenuously. Early in his career Dickens set himself to demolishing institutions that deserved to be demolished. Previous generations of Britannic authority had bequeathed a legacy of intolerable social abuses. The nasty hole of the debtors' prison in The Pickwick Papers (1836-37) and the vicious imbecility of Mr. Bumble the parochial beadle and his ilk in Oliver Twist (1838) were worthy objects of Dickensian outrage. But since then England has become a kinder, gentler nation, and nevertheless Dickens has continued in the vein of "sentimental radicalism." He assails men and institutions that really cannot be bettered—not because they are perfect, but because perfection is impossible. Dickens deploys a fantasist's sense of what is possible. His sensitivity to human suffering is pathologically acute; the fault is not uniquely his, but is characteristic of the age, which has gone too far in its recoil from earlier dreadful harshness.

He began by describing really removable evils in a style which would induce all persons, however insensible, to remove them if they could; he has ended by describing the natural evils and inevitable pains of the present state of being, in such a manner as must tend to excite discontent and repining. The result is aggravated, because Mr. Dickens never ceases to hint that these evils are removable, though he does not say by what means.

He and his wretched epigoni declaim "in what really is, if they knew it, a tone of objection to the necessary constitution of human society." In Bagehot's eyes, Dickens started out a sensible reformer and has become a dangerous revolutionary. Bagehot understands that Dickens—and Dickens alone among writers of fiction—exerts a power comparable to, or surpassing, that of the foremost politicians of the day. Writing in 1872, two years after Dickens's death, he declares, in the introduction to the second edition of The English Constitution, "The leading statesmen in a free country have great momentary power. They settle the conversation of mankind." The conversation is turning uncivil and clamorous.

And in settling what these questions shall be, statesmen have now especially a great responsibility if they raise questions which will excite the lower orders of mankind; if they raise questions on which those orders are likely to be wrong; if they raise questions on which the interest of those orders is not identical with, or is antagonistic to, the whole interest of the State, they will have done the greatest harm they can do.

Bagehot writes of "the lower orders of mankind," by which he means the working classes demanding universal male suffrage and who knows what else, as though they were proto-Morlocks. Dickens always had a special brief for the virtues of the lower orders—social, not human, orders. (Of course he also had a searing horror of the rat's-nest poverty where crime was incubated.) And it is clear from Bagehot's essay on Dickens that he believes the greatest novelist has thereby done political harm at least as pernicious as that done by the radical politicians.

George Bernard Shaw sees the same basic political change in Dickens's writing from the early novels to the late ones, but he praises what Bagehot condemns. Even as late as Bleak House (1852-1853), Shaw contends in a 1912 essay, Dickens identifies pockets of infection that can be lanced and healed without terrible difficulty, such as "Tom All Alone's, a patch of slum in a fine city, easily cleared away, as Tom's actually was about fifty years after Dickens called attention to it." With Hard Times (1854), Dickens sees the corruption is systemic, and the most drastic measures are necessary to save the body politic.

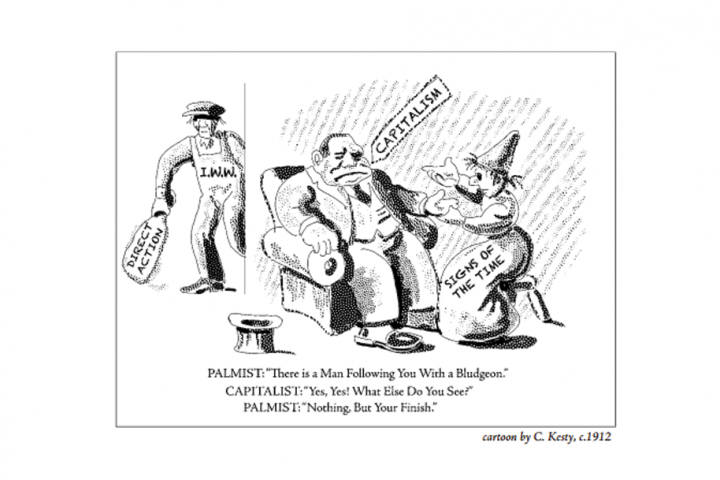

Clearly this is not the Dickens who burlesqued the old song of the ‘Fine Old English Gentleman,' and saw in the evils he attacked only the sins and wickednesses and follies of a great civilization. This is Karl Marx, Carlyle, Ruskin, Morris, Carpenter, rising up against civilization itself as against a disease, and declaring that it is not our disorder but our order that is horrible; that it is not our criminals but our magnates that are robbing and murdering us; and that it is not merely Tom All Alone's that must be demolished and abolished, pulled down, rooted up, and made for ever impossible so that nothing shall remain of it but History's record of its infamy, but our entire social system.

Fabian Socialism does not always sound so rapturously militant; Dickens plainly set Shaw ablaze. He sometimes did have that effect on men of the Left even harder than Shaw. Karl Marx told Friedrich Engels that Dickens had "issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists, and moralists put together." Where Marx saw truths pregnant with a glorious future, a Thomas Babington Macaulay perceived dangerous lies that ought to be strangled at birth: a felicity or two brightened Hard Times, but mostly it was "sullen socialism." The most passionate defenders and the most passionate detractors agreed Dickens was preaching socialism. But were they right to think so? Did Dickens develop into a utopian hothead? What was he really after?

Good and Evil

Dickens got his professional start at the age of 19 as a parliamentary reporter and quickly moved into a better job with the radical newspaper True Sun. As the Oxford don Robert Douglas-Fairhurst writes in his fine new account of Dickens's early years, Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist, "Dickens's own political views can be inferred from his position on a paper that was strenuously anti-Tory, as they can from his later blunt assessment of the Tories as ‘people whom, politically, I despise and abhor.'" Political vehemence, then, rang out not only in his fiction, but in his long journalistic career as writer and editor, and in his humanitarian activity. From Peter Ackroyd's monumental Dickens (1991), one learns that True Sun embraced Benthamite Radicalism, advocating untrammeled free speech and universal suffrage, condemning the Established Church and aristocratic rule. Evidently Dickens bought into the program at first, but made his break over the New Poor Law of 1834, which on the most rational Benthamite principles required all poor relief to be administered in workhouses; there inmates were segregated by sex, families were broken up, uniforms were mandatory, food was meager, and forced labor was onerous. Oliver Twist was born and raised in a workhouse; his famished entreaty to outraged authority, "Please, sir, I want some more," remains one of the most touching lines in English fiction. In Our Mutual Friend, written 27 years later, the old and destitute Betty Higden, who had been more than a mother to orphans and cast-off children, takes to vagabondage rather than seek shelter in a workhouse, preferring to die on her own terms, refusing the state's mingy solicitude.

For Dickens no social or economic proposal could stand if it was not founded on the unimpeachable heart. The elegantly swift-moving biographer Claire Tomalin, in Charles Dickens: A Life, touches upon the various causes he crusaded for: among them Ragged Schools, where volunteer teachers in the worst London slums would attempt to instruct all comers, "the homeless and starving, the disabled, even pupils who explained that their occasional absences were occasioned by prison sentences"; a Home for Homeless Women, as Dickens delicately called an asylum for prostitutes who wanted to amend their lives; the Metropolitan Sanitary Association, addressing the most urgent public health matters in an imperial capital where sewage ran down the middle of the streets, the Thames was a cloaca maxima, graveyards were so overcrowded that the dead burst from the ground, cholera epidemics broke out four times during Dickens's lifetime, and typhus, typhoid fever, dysentery, and smallpox were just part of life in the big city. Dickens wrote; he organized; he gave speeches. He gave his all.

Goodness was his natural element, but evil obsessed him. Individual meanness, unkindness, malice, and savagery always kindled his ire and fired his imagination; but pervasive social ills often bred these personal malignities, he believed, and he believed that from start to finish. Of course there are evildoers in his world as in our own who require no social pathology to provoke their viciousness: they are quite bad enough just as they were born. The sadistic dwarf Quilp, in The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-1841), who schemes to kill his wife by emotional attrition and marry the beautiful child Little Nell, never stood a chance of being anything but sickeningly repulsive, and it is only right that he dies a terrible violent death. Yet disgusting as Quilp is, he can also be antic and oddly winning in his villainous histrionics: it is as though a large cockroach were to scurry across your French toast, slam on the brakes, pull off a double-twisting layout back somersault, drop to one knee, and do a little shimmy with a white-gloved hand soliciting applause.

But while individual evil in Dickens can entertain by its very wild-eyed grotesquery, the larger social pathology only appalls.

On every side, and far as the eye could see into the heavy distance, tall chimneys, crowding on each other, and presenting that endless repetition of the same dull, ugly, form, which is the horror of oppressive dreams, poured out their plague of smoke, obscured the light, and made foul the melancholy air. On mounds of ashes by the wayside, sheltered only by a few rough boards, or rotten penthouse roofs, strange engines spun and writhed like tortured creatures; clanking their iron chains, shrieking in their rapid whirl from time to time as though in torment unendurable, and making the ground tremble with their agonies.

The human inhabitants of this blighted land writhe and shriek like the machines that govern their lives. Maddened armies of the unemployed march in the night, bent on violence that will only injure themselves the most, Dickens fears. Parents mourn their children starved to death and have no bread or pity for wandering beggars such as Nell and her grandfather. And all this desolation stretches "as far as the eye could see into the heavy distance." But Dickens's eye also takes in vistas of England's green and pleasant land and the human goodness that dwells there. His vision is always replete even when it is not exactly complicated.

Complications

Yet there are complications. To distinguish the singular and remediable evil in Dickens from the systemic and engrained is not so easy as Bagehot and Shaw suggest. In David Copperfield (1850), Mr. Murdstone, wicked stepfather, taskmaster, brute, seems like Quilp to have been morally misshapen from conception; and yet as the self-appointed earthly representative of a punishing god, he embodies a beastly religion that Dickens opposes to the light of true benevolent Christianity, and that has contributed to the deformity of multitudes. James Steerforth, the friend whom David idolized in childhood and adolescence, seems bedeviled by an inborn pride that can turn swollen and ugly, and he takes after his mother in that respect; however, the trait belongs not just to his family but to an entire social class accustomed to its superiority, and he seduces and exploits a beautiful young woman of plebeian birth whom, because of the class difference, he would never think of marrying. And then there is the low-born and just plain low Uriah Heep, whose sycophantic reiteration of his own humility, or "umbleness," scarcely veils his hideous resentment and unworthiness. Heep's attempt to hoodwink his decent employer, take over his business, and marry his daughter ultimately lands him in prison, and he makes David's skin crawl; yet in one strangely moving passage he reveals to David that, like his father and mother, Uriah was brought up to bow and scrape and know his place. Such self-abasement was obligatory if he hoped to get on in the world. The thought that Uriah was not simply born unctuously umble startles David and makes him wonder. Uriah is venomous and must be caged, yet one feels a certain pity for him. The social arrangements that produced him twist souls. How could he have turned out otherwise?

Can England, Dickens asks, still turn out other than it is? Hard Times poses the condition-of-England question, which is really the future-of-England question, more sententiously but also more harrowingly than the earlier novels. Here is the sort of reflection that Bagehot found so distasteful:

Surely there never was such fragile china—ware as that of which the millers of Coketown were made. Handle them never so lightly, and they fell to pieces with such ease that you might suspect them of having been flawed before. They were ruined, when they were required to send labouring children to school; they were ruined, when inspectors were appointed to look into their works; they were ruined when such inspectors considered it doubtful whether they were quite justified in chopping people up with their machinery; they were utterly undone, when it was hinted that perhaps they need not always make quite so much smoke.

Dickens's sneering at the ever so dainty manufacturing kingpins had a different ring in his day, when laissez-faire really meant what it said, and working conditions were commonly brutal, than it has in our time, when government reaches its hand into every business enterprise, and its paternalism becomes a deadening power-grab. Dickens smells the moral sulfur of the new industrial order founded on the calculus of political economy. To base a society on a parched idea rather than a rich imagination offends fatally against life itself. Such moralists of the Left as John Ruskin in Unto This Last, William Morris in "How I Became a Socialist," and Oscar Wilde in "The Soul of Man Under Socialism" say exactly that in advocating socialism. Dickens does not advocate socialism in this novel or elsewhere, but he warns the laissez-faire theoreticians that a populace malnourished on their intellectual gruel will turn on its masters:

…the poor you will have always with you. Cultivate in them, while there is yet time, the utmost graces of the fancies and affections to adorn their lives so much in need of ornament; or, in the day of your triumph, when romance is utterly driven out of their souls, and they and a bare existence stand face to face, Reality will take a wolfish turn, and make an end of you!

This is not a society so far gone in corruption that only violent revolution will save it; it is a society in need of the balm and restorative that a novelist of genius can provide it.

A Happy Confusion

The last novel that Dickens completed, Our Mutual Friend (1864-1865), is a moral tract—a very funny moral tract—in the form of a financial encyclopedia. Money-getting and hoarding and spending are considered in their endless variations; all the types are here in a society that thinks of nothing else so intently as it does about cash. Fascination Fledgeby, "a kind of outlaw in the bill-broking line," is the rankest dullard in ordinary conversation because his mind turns ever to the one thing needful. "Why money should be so precious to an Ass too dull and mean to exchange it for any other satisfaction, is strange; but there is no animal so sure to get laden with it, as the Ass who sees nothing written on the face of the earth and sky but the three letters L.S.D.—not Luxury, Sensuality, Dissoluteness, which they often stand for, but the three dry letters" (for pounds, shillings, pence). The young beauty Bella Wilfer, raised in modest circumstances, has rich prospects but fears what wealth might do to her:

"And yet, Pa, think how terrible the fascination of money is! I see this, and hate this, and dread this, and don't know but that money might make a much worse change in me. And yet I have money always in my thoughts and my desires; and the whole life I place before myself is money, money, money, and what money can make of life!"

Money can only make a wasteland of life, Dickens teaches, unless one sees what is genuinely valuable. Fascination Fledgeby chisels the wrong man and gets the thrashing he deserves. Bella proves worthy of true love and gains a fortune into the bargain.

In notes on his 1835 journey to England, Tocqueville presaged the Dickensian insight about the importance of money to the natives:

Wealth [for the English] is identified with happiness and everything that goes with happiness; poverty, or even a middling fortune, spells misfortune and all that goes with that. So all the resources of the human spirit are bent on the acquisition of wealth. In other countries men seek opulence to enjoy life; the English seek it, in some sort, to live.

In the chapter on "Laissez-Faire" in the 1839 essay "Chartism," Thomas Carlyle excoriated the current social order, in which "Cash Payment" had become "the universal sole nexus of man to man." Dickens knew Tocqueville and Carlyle were right, to a significant degree; yet he also offered a cure for the disorder—not a general cure, but one that works for those who can accept elementary wisdom about how to live. (Admittedly it helps, as it does for Bella, if the husband you thought was poor turns out to be rich.)

In certain respects The Old Curiosity Shop and David Copperfield present as subversive a depiction of systemic social wrongs as Hard Times and Our Mutual Friend, while the two later novels present as hopeful a depiction of individual righteousness as the two earlier ones. The prime Dickensian lessons of his later works remain essentially those of the earlier works. The ghost of Jacob Marley in A Christmas Carol (1843) wore the chains of greed and selfishness that he forged in life; Ebenezer Scrooge got the most famous spiritual make-over in modern literary history and learned the true meaning of Christmas, or the Gospel According to Charles, in liberality born of fellow-feeling. Dickens hated greed and selfishness, and he loved liberality and human sympathy, just as much in 1842 as he did in 1865. These vices are hard to overcome and these virtues hard to achieve; and it was always the struggle of the individual spirit that most bemused Dickens. Justice is not something to be wrested wholesale from an indecent, worthless society, as Shaw insisted; Dickens never saw the whole society as worthless as long as there were worthy persons in it, or persons striving to become worthy. This most earnest of reformers abominated unnecessary suffering, yet he approached it not with a revolutionary's rage but rather with a born novelist's sensibility. He knew that social change can take place only in the movement toward light of particular souls, and that such change may prove slow at best and less than momentous in sum. He knew too that some terrible human pains are unavoidable; he just disagreed with someone like Bagehot as to what these were. His fundamental belief contrasted sharply not only with the iron-hearted recalcitrance of the hard-core conservatives but also with the limitless hopefulness of the socialists, as exemplified in Russian dramatist Maxim Gorky's praise of Lenin's "burning faith that suffering was not an essential and unavoidable part of life, but an abomination that people should and could sweep away."

So despising and abhorring Tories did not mean Dickens lacked the basic instincts of conservatism in the broad sense; and resisting the socialist call to revolution did not mean Dickens lacked radical mettle. In an age abundant in drifting souls and moral desperadoes, he accepted the world as it was even while he sought to repair it where it needed fixing. He battled for the general improvement of mankind but yielded to the inexorable. This is wisdom that both conservatives and liberals rightly claim for their own, however the proportions might differ.

Saul Bellow's Moses Herzog used to play a game with his little daughter: was the person in his story the baldest hairy man or the hairiest bald man, the fattest skinny man or the skinniest fat man? Was Charles Dickens the most conservative of liberals or the most liberal of conservatives? Only some such happy confusion can do justice to a man every bit as actual as the characters he created.