Five years into a life sentence for a gang initiation murder, Jessie Con-ui murdered a prison guard. A videotape of the crime, played at Con-ui’s trial, showed him pausing, in the course of stabbing the victim 200 times, to wash his hands and remove a gum packet from the dying guard’s shirt pocket. According to newspaper accounts, Con-ui’s confessed motive for the crime was that the guard had “disrespected” him by searching his cell. Another inmate testified that Con-ui planned the killing to provoke a transfer to a cushier prison. Charged with and convicted of murder, Con-ui escaped a death sentence because one juror “felt bad” for Con-ui’s mother and told others in deliberations, “There’s enough bad things in the world the way it is, and I can’t see taking a life.”

Why does America bother to retain the death penalty? In Con-ui’s case it’s hard to say what box wasn’t checked justifying a death sentence, if ever a crime warrants death. Doubts about guilt or the offense’s gravity? None. Concerns that the defendant’s judgment was impaired by drugs or alcohol? None. Questions about whether the murder was aberrant and not reflective of the defendant’s character? None. There were, of course, “mitigating” factors, vented elaborately at the sentencing hearing—a deprived childhood and a father who sometimes made the defendant sleep in a car. But prosecutors reviewing Con-ui’s verdict must wonder, even when confronted with the most heinous crimes, whether pursuing a capital sentence is worth the expense.

And expensive it is. Prosecutors must prepare for two trials—first on guilt, and then on what is infelicitously denominated “death-eligibility.” Byzantine rules, crafted over four decades of Supreme Court opinions, specify which “aggravating factors” transform the ordinarily horrible murder into an especially horrible “death-eligible” murder. Enter the parade of witnesses, including sobbing kin of the victim. Then come the defense witnesses, summoned by skillful counsel (well-funded, at state expense) gesturing at inchoate “mitigating factors” that return the murder to the category of the ordinarily horrible. Almost all states now demand a unanimous jury verdict on the question of “death-eligibility.”

Assume that a unanimous jury returns a death sentence and the trial judge ratifies it. Decades of appeals, petitions, and emergency motions follow. The condemned does not lack for advocates. Countless law firms and schools enlist eager associates and students, all acting, as it’s optimistically said, “pro bono publico.” In some jurisdictions, judges in capital cases are liberated from any trammeling notions of judicial duty—i.e., to follow the law. In one escapade, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals invalidated a death sentence on the premise that the condemned man had a First Amendment right to know the dosage of the poisons the state intended to administer. The claim baffled Supreme Court Justices otherwise disposed to sympathize with almost any argument raised by capital defendants.

Jump forward about 20 years. The legal hurdles have all, improbably, been surmounted, and the day of execution has arrived. How hard is it to end a human life? For centuries, hanging was deemed adequate, with guidelines on rope diameter and length, calibrated to the condemned man’s weight, to ensure the neck snaps without severing the head. But over the course of the 20th century hanging was rejected as barbaric and unscientific. Electrocution emerged as the modern answer to these concerns, but it too was rejected eventually on the same grounds. Most states then adopted a “three-drug protocol.” The design of the current procedure is partly driven by aesthetic concerns: the execution is staged so that witnesses are not overly alarmed. In particular, the use of a muscle relaxant ensures the condemned doesn’t startle observers by spasming. As a journalist present at many executions observed, the final act is “so clinical as to be anticlimactic.” The impulse to mask an execution’s brutal nature—the culmination of decades of agonized equivocation—strengthens the suspicion that 21st-century America lacks the will to perform the act at all.

The End of History

In 1989 political scientist Francis Fukuyama wrote that the close of the Cold War probably marked “the end of history”—the fulfillment of “mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” A defining aspect of this soon-to-be universal civilization was the recognition of a common humanity, which entailed “the spread of compassion, and a steadily decreasing tolerance for violence, death, and suffering. This comes to light, for example, in the gradual disappearance of capital punishment among developed countries.”

In Europe, Fukuyama’s account—both as description and prediction—has been borne out. The last execution on western European soil occurred in 1977, when France deployed its guillotine on a Tunisian-born murderer. Several countries in central and eastern Europe persisted in applying the death penalty through the 1990s, but today only outcast Belarus retains capital punishment.

Miscellaneous and redundant European Union conventions have codified the death penalty’s abolition. The E.U. has also been at the forefront of pressuring nations worldwide to abolish capital punishment. Any country, however obscure and wracked by terrorism and violent crime, which imposes a single death sentence can expect criticism from an E.U. functionary. When, in January 2018, the Israeli Knesset voted preliminarily to authorize capital punishment for convicted terrorists, the E.U. Delegation to the State of Israel promptly criticized the move in a tweet that intoned, “The death penalty is incompatible with human dignity.” And when, in July 2018, the president of Sri Lanka intimated that he was open to ending his nation’s 42-year moratorium on the death penalty, the E.U. threatened to withdraw the tiny island nation’s favored trade status.

If it ever comes to pass, the death penalty’s worldwide abolition would represent a culminating moment in human history. Since Thomas Hobbes, Western thinkers have predominantly rejected retribution as a basis for punishment. The Enlightenment project, argued Leo Strauss, has striven to banish, or channel, the spirited part of the soul—the part that “in its normal form [manifests itself] as a zeal for justice, or moral indignation…which easily turns into vindictiveness or punitiveness.” Capital punishment’s abolition reflects a broader rejection of this spirited, punitive impulse.

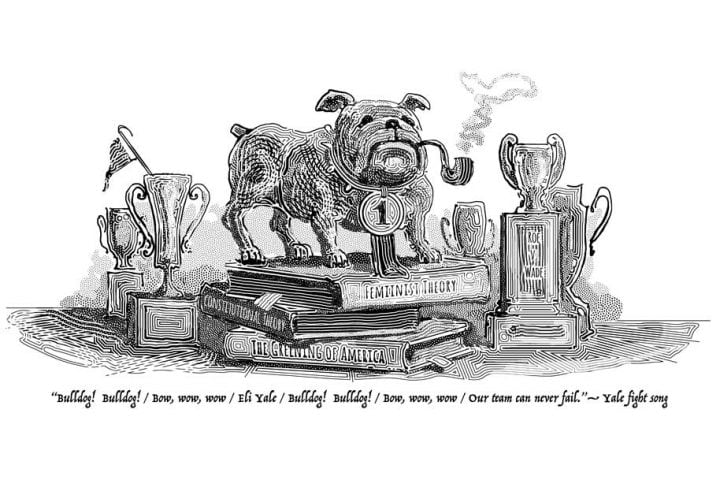

One curious aspect of Fukuyama’s argument is that although he anticipated this development, he did not embrace it unreservedly. He sprinkles his book The End of History and the Last Man (1992) with quotations from Alexis de Tocqueville, Friedrich Nietzsche, and C.S. Lewis, all of whom looked with horror at Nietzsche’s “last men” and Lewis’s “men without chests” who, stripped of spiritedness, are “incessantly endeavoring to procure the petty and paltry pleasures with which they glut their lives,” as Tocqueville put it. A similar note was struck by Walter Berns in his polemic defending the death penalty, For Capital Punishment (1979), at a time when the practice had almost ceased. Berns despairingly invoked Nietzsche’s critique of the “pathologically soft” last man: “There is a point in the history of society when it becomes so pathologically soft and tender that among other things it sides even with those who harm it, criminals, and does this quite seriously and honestly.” For Berns, only a decline in spirited moral indignation, and squeamishness about—even aversion to—punishing criminals, could explain the apparent direction of American attitudes towards the death penalty.

Civilizations and the Death Penalty

Just four years after Fukuyama published The End of History, Harvard’s Samuel Huntington countered with The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996). For Huntington, mankind remained, and for the foreseeable future would continue to remain, stalled in history. He saw the world divided among competing civilizations, rooted in different pasts, valuing incommensurable principles. To think these civilizations were destined to embrace the European Convention on Human Rights as the pinnacle of human existence, wrote Huntington (quoting British historian Arnold Toynbee), reflects the “egocentric illusions” and “impertinence of the West.”

Fukuyama and Huntington presented opposing frameworks for viewing the world and predicting its trajectory. Most pertinent here, Fukuyama’s thesis predicted a globally spreading disaffection with capital punishment. At first blush, he seems to have been proven right. As Amnesty International points out, in 2017, a record-high number of nations—170 of 193 United Nations voting members—are “execution-free.”

Yet the formally democratic number-counting employed in the U.N. General Assembly can obfuscate deeper global trends. Instead of considering countries en masse, as do the United Nations and Amnesty International, let us consider the status and direction of capital punishment in each of the civilizations described by Huntington.

Two civilizations—the Sinic and Japanese—show no movement toward abolition. For China, exact numbers are impossible to come by, but it is likely the country executes between 2,000 and 4,000 people each year. And Japan is a persistent embarrassment to those who portray America’s attachment to the death penalty as unique in the “industrialized” or “civilized” world. From 2012 to 2017 Japan executed between three and eight people each year, which means that per number of homicides, the Japanese execution rate exceeds that of the United States. Moreover, in July 2018, with little forewarning, Japan executed 13 people, all associated with the 1995 sarin gas attack.

The Islamic civilization is difficult to characterize. Those inclined to see Western trends focus on smaller, more moderate countries such as Morocco, which hasn’t executed anyone since 1993, or Indonesia—with the world’s largest Muslim population—which hasn’t executed anyone in two years. Conversely, two of the most influential Muslim nations, Iran and Saudi Arabia, continue to employ capital punishment at high levels (300-800 per year in Iran, 50-150 per year in Saudi Arabia). Pakistan, the second-largest Muslim country, emphatically restored capital punishment in the aftermath of the 2014 Peshawar massacre. An even more cautionary story, for those optimistic about abolitionism in the Islamic world, is that of Jordan. In 2005 King Abdullah II announced that “in coordination with the European Union” he anticipated Jordan would become the first Middle Eastern nation to abolish the death penalty. Yet after a moratorium of several years, Jordan restored the death penalty in 2014 amid concerns about terrorism.

The Hindu and Buddhist civilizations also supply evidence for both the Fukuyama and Huntington theses. On the one hand, the leading countries in each civilization—India and Thailand—have executed a total of only four people between 2010 and 2018. On the other hand, both countries regularly issue death sentences, which have widespread public support. A 2018 poll published in the Bangkok Post found that 92% of Thais desired to retain the penalty, and India has witnessed a resurgence in interest in retaining and even expanding capital punishment after a series of highly publicized child rape cases. More broadly, any claim that these civilizations are converging on Western secularism, with its gentler punishment practices, fails to acknowledge the resurgence of militant Hinduism in India and militant Buddhism in Sri Lanka and Myanmar—developments Huntington predicted and which point to a persistent division of the world into competing civilizations.

The African civilization is touted by Amnesty International and other Western observers as a success story for death-penalty abolitionism, with roughly three quarters of its countries abandoning capital punishment. Yet there are significant outliers. Nigeria, the continent’s most populous nation, has over 2,000 people on death row. Although Nigeria hasn’t conducted any executions recently, its courts hand out hundreds of death sentences every year, and the country’s president has repeatedly spurned Western criticisms of this practice. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the abolition of the death penalty, where it has occurred in Africa, reflects a shift in attitudes towards human rights.

Both Latin American and Orthodox civilizations have been hailed as either exclusively or overwhelmingly abolitionist. With respect to Latin American countries, however, the governments’ repudiation of the death penalty coexists with astonishing levels of violence: Latin America contains 17 of the 20 nations in the world with the highest homicide rates. Abolitionists indefatigably promote the contested claim that “the death penalty does not deter,” but, confronted with a national homicide rate five times that of the United States, Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president since January, campaigned on a promise to restore capital punishment. There can be little confidence that Latin America will remain abolitionist in the face of violent crime rates that are multiples of those experienced in the West.

All Orthodox countries (except the aforementioned Belarus) are abolitionist and praised as such by Amnesty International. Consider, in this regard, the chastening reminder of one Orthodox leader to his American counterparts that the death penalty is nothing more than “vengeance on the part of the state.” It is a remark that could easily have been uttered by any E.U. bureaucrat, and suggests this leader has wholeheartedly embraced the E.U. understanding of punishment practices. His name? Vladimir Putin.

Davos Man

Do non-Western leaders parrot the language of abolitionism to virtue-signal to, and secure financial aid from, the European Union (or in Putin’s case, simply to tweak the United States) rather than out of genuine agreement about underlying principles? If so, how long will non-Western nations continue this charade? Huntington emphasizes that population and wealth trends point dramatically in favor of non-Western civilizations. According to PricewaterhouseCoopers projections for the year 2050, Thailand will have a larger GNP than Spain, Russia will have a larger GNP than every European nation, and the 27 nations that constitute the European Union will, collectively, have a GNP of only 60% that of India and 40% that of China. In such a world, will non-Western countries grovel before the European Union and pretend to aspirations—such as death penalty abolitionism—that they do not share?

When viewed in Huntington’s framework, reports of capital punishment’s death in the non-Western world are greatly exaggerated. The success of abolitionism is contingent on continuing Western power and influence, which are likely waning, and declining rates of terrorism and domestic violence, concerning which no confidence is warranted.

Even in what Huntington calls Western civilization, abolitionist trends may not be as durable as advertised. Western elites regularly underestimate public support for capital punishment. When, in 2015, Supreme Court Justices Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg mused that “the death penalty is dying away” and that “a majority of Americans” reject capital punishment, Justice Antonin Scalia astutely responded: “Welcome to Groundhog Day.” We have indeed been here before. In 1972, in the course of deliberations in the case Furman v. Georgia, Justices Potter Stewart and Byron White wondered whether “capital punishment…has, for all practical purposes, run its course.” Yet within two years of the Furman decision’s imposing a moratorium on capital punishment, 35 states re-enacted death penalty statues.

In 2016, death penalty referenda appeared on three state ballots. In Oklahoma, voters rejected an effort to repeal the death penalty by a two to one margin. In Nebraska, the margin was 60% to 40%. Remarkably, the result in California was nearly the same: 53% to 47%.

European elites have been more effective than their American counterparts in transforming criminal punishment practices. But their success may simply prove that European political systems are more undemocratic than those of America. After West Germany abolished capital punishment in 1949, Justice Minister Thomas Dehler was forthright: “I say in all clarity: I do not care about the ‘people’s conviction,’ that is, the opinion of the man on the street.” He subsequently suggested that those in favor of the death penalty were so because of “genetically inherited” dispositions.

The elitist, morally crusading aspect to much of the Western abolitionist movement calls to mind one of Huntington’s lasting contributions to understanding the modern world—the “Davos Man.” Introduced in his essay “Dead Souls: The Denationalization of the American Elite,” and expanded upon in later writings, Davos Man—who takes his name from the town in the Swiss Alps where the World Economic Forum meets—is distinguished by his cosmopolitan attachment to the Enlightenment’s abstract ideals, rather than to the nation state of his birth. Huntington spelled out the implications of this belief system for Davos Man’s views on international trade (no tariffs) and immigration (open borders); but Davos Culture cosmopolitanism doubtless generates, or at least corresponds with, certain attitudes towards criminal punishment. The impulse to punish, rooted in a spirited and vengeful defense of one’s community, is atrophied in Davos Man. In his world view, past wrongs are dead weight losses, to be disregarded in cost-benefit calculations; instead, he rationally calculates the least costly punishment to achieve some level of general deterrence, weighing also the benefits of promptly re-integrating the criminal into society. Capital punishment, now extraordinarily costly, with few easily discernible benefits, he discards as a hopeless atavism.

Many non-Westerners are struck by what Huntington calls the “hypocrisy and double standards” of Westerners, which is the “price of [their] universal pretensions.” However weighty the arguments for abolishing the death penalty, at least in the peaceful and lawyered Western world, it is odd that Davos Man demands this reform in nations that are not his home and where conditions are inconceivably different from those that predominate in the West. Only a peculiar cast of mind would blind one to these nuances and lead one to think that, as Huntington wrote in The Clash of Civilizations, all “non-Western people should adopt Western values” with respect to capital punishment, or, more specifically, what Davos Man regards as “Western values.” The global crusade against the death penalty, enshrouded in a gauzy haze of self-congratulation, is amenable to a cynical interpretation: Notwithstanding Davos Man’s confidence in his own probity, he is a man without moral imagination.

Agonized Retention

April 15, 2013, marked the 117th running of the Boston Marathon, a celebration of one of Western civilization’s iconic victories. At 2:49 p.m., near the finish line, two makeshift bombs were detonated, shattering the festivities and killing three people. Within days, the culprits—Chechnyan brothers, fueled by anger toward the West—were tracked down, one dead and one alive.

President Obama’s Justice Department pursued the death penalty against the surviving brother, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. The decision was controversial, as the last execution in Massachusetts had occurred over 60 years earlier. Tsarnaev’s guilt was easily proven, but difficulties arose at the sentencing phase. He had a team of five experienced defense lawyers. Among the witnesses summoned on his behalf was Helen Prejean, a globe-trotting Catholic nun and death penalty abolitionist. She testified Tsarnaev was “absolutely sincere” in his plea for forgiveness.

The prosecutors had to cross-examine a witness likely viewed sympathetically by the predominantly Catholic jury. The Boston-based prosecutor began as follows:

Q. Sister, you’re not based in Massachusetts,

are you?

A. Correct.

Q. You don’t live here?

A. No.

Q. And your order is not located here?

A. Some—sisters are related in different

branches, so some of our cousin sisters of

St. Joseph are here.

Q. But not you?

A. But not me.

The best cross-examinations plant an idea and rouse the listener to draw out a chain of reasoning. The cross-examination of Sister Prejean invited the following thought in the jurors: You are not from the community that was devastated by this crime. You just jet around where you have no business. Who are you to lecture us about the “sincerity” of the defendant? With four questions, Sister Prejean was transformed in the eyes of the jurors from a kindly nun to a sanctimonious outsider. The jury unanimously voted death.

It is unlikely that Tsarnaev will ever be executed. In the decades of appeals that have just begun, some legal error, however, trivial, will be identified. Nonetheless, the answer to the question that introduced this article seems to be: Americans retain the death penalty because a sizable number think it sometimes just and necessary. Ours may be an agonized retention of capital punishment, but perhaps the emphasis should be laid not so much on the agony as on the retention. Despite the contempt for the retentionist view espoused by proper-thinking people, many Americans (and Japanese, Chinese, Muslims, Hindus, and even a few Europeans) remain unpersuaded by the abolitionist argument.

It is possible that at some future date the world will be so prosperously harmonious that all of humanity will reject capital punishment. Until then, as long as we remain mired in the violence and civilizational conflict of history, the resolve to punish and even execute those who have wronged our community will likely remain a testament to human spiritedness.

The evidence suggests that the death penalty is far from dead.