Books Reviewed

Philip Bobbitt is the Herbert Wechsler Professor of Federal Jurisprudence at Columbia University School of Law, a distinguished lecturer and senior fellow at the University of Texas School of Law, and a member of the Hoover Institution’s task force on national security and law. He was counselor on international law in President Clinton’s Department of State; and on Clinton’s National Security Council staff Bobbitt was in charge of intelligence and, later, strategic planning. His new book is a serious attempt to place terrorist and anti-terrorist warfare in the context of the history of war—indeed, of the nature of human relationships. This is a big, ambitious book that draws its conclusions about terrorism today from nothing less than a made to order Weltanshauung—complete with new terminology and reminiscent of Hegel more than Toynbee—which describes how and why states and those who have rebelled against them have behaved and will behave. Instead of familiar sloganeering on such questions as whether to torture terrorists or to intervene in places like Iraq, Bobbitt brings some genuine historical insights to bear on the sweeping question of how America should lead mankind into the future. Here then a quintessential Establishmentarian gives the impression that he is thinking “outside the box.” But no….

After 529 sometimes brilliant, usually convoluted, often confused pages, Bobbitt quotes the British historian Sir Michael Howard to sum up his conclusion about why the 21st-century wars by and against terrorists came about and what Americans should do:

[A]n explicit American hegemony may appear preferable to the messy compromises of the existing order, but if it is nakedly based on commercial interests and military power it will lack all legitimacy. Terror will continue and, worse, widespread sympathy with terror. But American power placed at the service of an international community legitimised by representative institutions and the rule of law, accepting its constraints and inadequacies but continually working to improve them: that is a very different matter. It is by doing this that the US has earned admiration, respect, and indeed affection throughout the world over the past half century.

Boilerplate! The author’s apparent flights of unfettered reason boil down to thoughts and policies that are standard issue in the U.S. national security bureaucracy—the sort of wisdom one encounters in, say, the charter of the Department of Homeland Security or the papers of recent NSC staffers. This is the intellectual novocaine that is injected into senior officers at our war colleges, that makes five-star conferees nod, the wisdom that most of our foundations pay for. In short, this book defines the “box” within which all the parts of our foreign policy Establishment rattle dysfunctionally.

* * *

According to Bobbitt, today’s terrorism is the effort that certain cultures make to resist the spread of what he calls “market states of consent,” of which the U.S. is the exemplar, and to ensure for themselves what he terms “states of terror.” To defeat them, Bobbitt counsels turning the U.S. armed forces into a vast “constabulary” that would occupy all places and pacify all peoples threatened by “terror” and reform them into “states of consent.” Terror itself would be the enemy. And while these forces would have to kill some non-consenting irreconcilables, American troops would operate primarily by applying positive and negative incentives to whole populations. All their actions would have to be ruled by law, by which Bobbitt means the consensus of the international community (more on that below) and the U.S. domestic laws that would flow from that consensus.

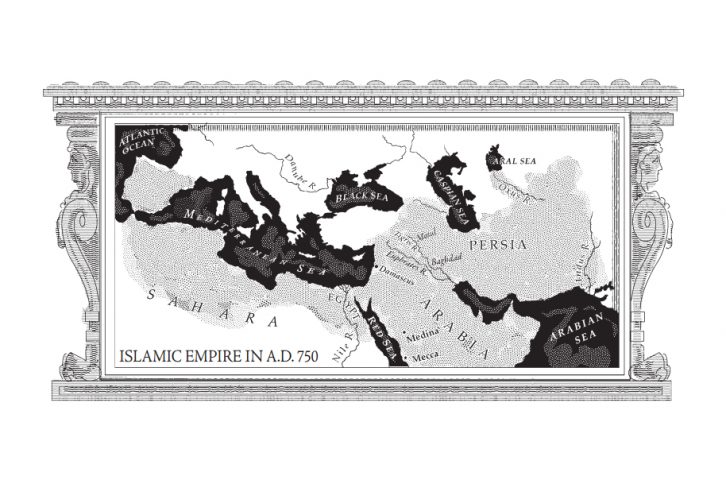

Every historical era, argues Bobbitt, has a typical form of government or society, and a corresponding type of terrorism. The Crusades, he tells us, were medieval society’s terrorism. Bobbitt claims that “the crusaders” massacred Jews and that the whole enterprise was blessed by the likes of St. Bernard of Clairvaux. But in fact these massacres were the work of heretics who targeted the Church hierarchy and the wealthy before turning to others. Reducing the Crusades to these banes of Europe’s secular and religious authorities shows the shallowness of Bobbitt’s erudition. He argues that the princely states of the Renaissance imposed their writ through mercenary armies and in turn spawned lawless bands of mercenaries. The kingly states of the 17th and 18th centuries had to fight off revolts from pretenders to the throne as well as from motley feudal remnants. The revolutionary state-nations of the late 18th and early 19th centuries (inexplicably Bobbitt lumps together Napoleon and the American Founders) claimed to give meaning to life through nationhood and hence had to fight pirates and anarchists, who spread terror to challenge the very idea of nationalism. The 19th and 20th-century nation-state claimed to ensure economic security and progress, but had to combat terrorist groups—various permutations of Communism and fascism that murdered civilians in order to deliver them from socio-economic exploitation. The postmodern “market state,” however, exists to maximize choice because postmodern society and government are no longer rigidly hierarchical, but based on fluid networks. No surprise then that terrorists in the age of the “market state” should be animated by opposition to choice, and that they should organize themselves in fluid networks that exploit the opportunities the market state affords for wreaking massive damage.

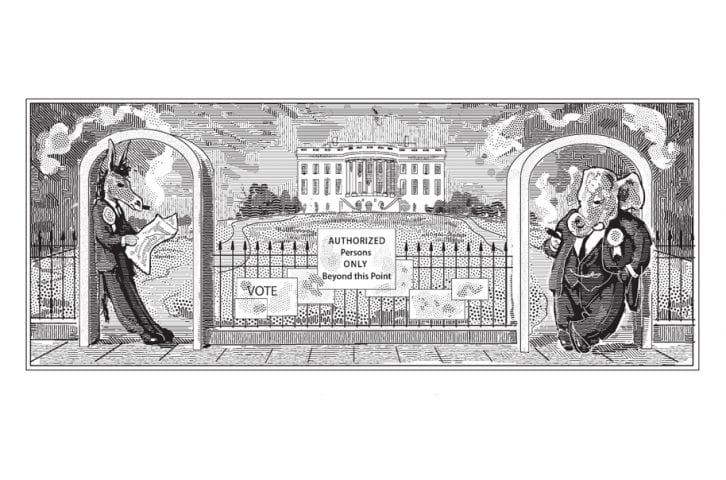

The theoretical framework’s second part, superimposed on the first, is the distinction between “states of consent” and “states of terror.” The author tells us that this is also the distinction between “legitimate” or “law abiding” states, and illegitimate ones based on lawless force. This distinction, which he substitutes for Aristotle’s distinction between regimes that pursue the good of the whole and those seeking the good of the ruler exclusively, is problematic. Whenever the reader comes across Bobbitt’s copious references to “law” he is tempted to ask: “whose law?” More important, are there not many bases for consent? Why should those who refuse consent to the prevailing socio-political forms be deemed lawless or terrorist?

This objection is especially relevant to Bobbitt’s so-called “market state.” Its quintessential job, he says, is physical protection of civilians against all major disorders—specifically including natural disasters and deprivations of “human rights,” especially the rights of women—in order to maximize choice. But some people, notes Bobbitt, choose precisely to live according to definitions of human rights different from his. By what right does he pretend to restrict the choices of, say, Muslims (women as well), to be left alone to live polygamously? Bobbitt answers almost well: there are some things to which man may not consent, rights that he may not give up because they are integral to his humanity. He cites the Declaration of Independence to this effect. Crucially, however, he neglects what gives the Declaration its power: Nature and Nature’s God. Without that, the notion of inherent rights is just another opinion.

* * *

Bobbitt also neglects that though such first principles, rightly understood, establish the inherent superiority of well-ordered human freedom, and hence our absolute right to make war on anyone who impairs our freedom, they do not authorize us in any way to restrict those who are not part of our body politic who choose to live in denial of human rights. This is the understanding that our founders embodied in the Declaration. By contrast, Bobbitt and the Establishment he represents take the superiority of diversity or multiplicity of choice as warrant for restricting those who choose against it. They believe it is right, indeed obligatory, to interfere with and to constrain other people’s benighted choices—for example, to stop ethnic cleansing or genocide in places like Darfur and Rwanda and Iraq. Thus interfering and constraining, forcing men to be free, is “the new way of war.”

Yet what Bobbitt proposes, what our Establishment recommends, is not war in the dictionary sense of the word. He acknowledges that genocide in Darfur is the work of Sudan’s government, and proposes radically increasing the number of “peacekeepers” there—but certainly not to make war on Sudan’s Arab government or on the Arab population carrying out the genocide. But then to do what? He does not say. He knows that our involvement in foreign quarrels brings those quarrels to America’s shores, that many who terrorize Americans do it because they feel that our actions, our very being, are in opposition to them. But this does not move Bobbitt either to renounce intervention or to intervene to kill, crush, and intimidate. Instead, his and our Establishment’s solution is to do the same thing at home and abroad, namely, to flood civilian life with largely non-lethal militarized police (or military in police mode) with lots of intelligence, lots of administrative capacity, lots of means of bribery (it helps compliance), and lots of legitimacy.

Whence the legitimacy? Bobbitt is adamant that it must come from law. Although he attempts to qualify or at least to obscure his legal positivism, in practice law means for him any published procedure on which there is “consensus.” But whose consensus? He denies that the consensus of the American people, by itself, is enough. “Law” must mean the consensus of officials who transcend individual polities and somehow represent the entire world, people like himself. Only such consensus can legitimize the constraints that need to be imposed on the world in order for the “market state” to function. The reader is not surprised that Bobbitt does not ask by what right such people are mankind’s legitimate lawgivers. That is because the law that inspires and underlies his construct is the indirect kind of the European Union and of the United Nations.

How fantastic is the notion that such international institutions can curb terrorism may be seen by the fact that in March 2008 the Islamic Conference (over a fourth of the United Nations’ membership) persuaded the U.N. Human Rights Council to recommend amending the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to remove protection from any speech or act that insults Islam, as a first step toward criminalizing any insult to Muslims or the Prophet Mohammed.

Consensus? No doubt, there is lots of it within our foreign policy Establishment, and Professor Bobbitt’s book expresses it better than most. Indeed, it makes the argument for universal democratization and human rights better than Robert Kagan does, the argument for coercive interrogation better than John Yoo—never mind George W. Bush—and the Liberal Internationalist case for waging war through incentives, bribery, and agreement with foreign governments better than the Democratic candidates for president in 2004 and 2008. In this book Philip Bobbitt has made the case for that consensus more fully, more subtly, and more persuasively than I have ever seen.

The problem is that his arguments are largely irrelevant to war and that the Establishmentarians who make them are out of touch with reality. To wit:

(1) Exciting as “The nation-state is passé!” may be as a topic at five-star conferences and as ardently as Eurocrats and their American admirers may wish it were true, the fact is that humanity today lives in such states, and that the ones from which terrorists come looking for us, whence the money and inspiration for terrorism come, are thoroughly capable of turning terrorism on or off. They have chosen to turn it on. What will it take to make them turn it off?

(2) Only the peoples of any given nation-state can decide what they regard as legitimate. Three decades of Euro-rule by unelected bureaucrats who regard each other as embodying Legitimacy should have taught us that all peoples so ruled end up regarding their rulers as self-serving, and would not consider sacrificing anything at their behest. Hence any attempt to substitute the kind of international consensus dear to Bobbitt for traditional American decisions about America’s national interest would Europeanize America.

(3) Armies are blunt instruments of war, essentially negative in character. Any further regimentation, not to mention militarization, of American civilian life will further dry up the only true source of domestic security, namely, the American people’s immunological reaction against those in our midst who may not have the country’s best interests at heart. This fellow feeling, not razor wire and identity cards and “security,” kept America secure and civil during the 20th century. Thinking of the U.S. government’s role at home in terms commensurable with notions of “the new way of war” and “market states” is no less ludicrous for being logical.

(4) The proper use of armies is to crush enemies, not to mix with them for hazy ends. Even as the makers of “international consensus” find in Islamic violence reasons to respect Islamists of which they had scarcely been aware, so they may one day find that an America that crushes its tormentors and moves on might not be so unsophisticated after all.