No English-language newspaper reported on it at the time, nor has any cited it since, but the speech Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán made before an annual picnic for his party’s intellectual leaders in the late summer of 2015 is probably the most important by a Western statesman this century. As Orbán spoke in the village of Kötcse, by Lake Balaton, hundreds of thousands of migrants from across the Muslim world, most of them young men, were marching northwestwards out of Asia Minor, across the Balkan countries and into the heart of Europe.

Already, mobs of migrants had broken Hungarian police lines, trampled cropland, occupied town squares, shut down highways, stormed trains, and massed in front of Budapest’s Keleti train station. German chancellor Angela Merkel had invited those fleeing the Syrian civil war to seek refuge in Europe. They had been joined en route, in at least equal number, by migrants from Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. For Hungarians, this was playing with fire. They are taught in school to think of their Magyar ancestors as having ridden off the Asian steppes to put much of Europe to the torch (Attila is a popular boys’ name), and they themselves suffered centuries of subjugation under the Ottomans, who marched north on the same roads the Syrian refugees used in the internet age. But no one was supposed to bring up the past. Merkel and her defenders had raised the subject of human rights, which until then had been sufficient to stifle misgivings. In Kötcse, Orbán informed Merkel and the world that it no longer was.

Orbán was preparing a military closure of his country’s southern border. That Europe’s ancient nation-states would serve in this way as the first line of defense for the continent’s external borders, such as the one between Hungary and Serbia, was exactly what had been assumed two decades before in the founding treaties of the European Union, the 28-nation federation-in-embryo centered in Brussels and dominated by Merkel’s Germany. But sometime after Hungary joined the E.U. in 2004, this question of Europe’s borders had become complicated, legalistic, and obscured by what Orbán called “liberal babble.” Orbán now had to make a philosophical argument for why he should not be evicted from civilized company for carrying out what a decade before would have been considered the most basic part of his job. His Fidesz party had always belonged to the same political family that Merkel’s did—the hodgepodge of postwar conservative parties called “Christian Democracy.” Now, as Orbán spoke, it was clear the two were arguing from different centuries, opposite ideologies, and irreconcilable Europes.

“Hungary must protect its ethnic and cultural composition,” he said at Kötcse (which more or less rhymes with butcher). “I am convinced that Hungary has the right—and every nation has the right—to say that it does not want its country to change.” France and Britain had been perfectly within their prerogatives to admit millions of immigrants from the former Third World. Germany was entitled to welcome as many Turks as it liked. “I think they had a right to make this decision,” Orbán said. “We have a duty to look at where this has taken them.” He did not care to repeat the experiment.

Migrants kept coming, and the European mood shifted. In Germany, Alternative for Germany (AfD), a party founded by economists to protest European Union currency policy, shifted its attention to migration and began to harvest double-digit election returns in one German state after another. The Polish government fell after approving a plan to redistribute into eastern Europe the migrants Merkel had welcomed. But if any European politician symbolized this reassessment, it was Orbán. Signs appeared at rallies in Germany reading “Orban, Help Us!” His dissent split Europeans into two clashing ideologies. With the approach in May 2019 of elections to the European Union parliament, the first since the migrant crisis, Europeans were being offered a stark choice between two irreconcilable societies: Orbán’s nationalism, which commands the assent of popular majorities, and Merkel’s human rights, a continuation of projects E.U. leaders had tried to carry out in the past quarter-century. One of these will be the Europe of tomorrow.

Versailles, Moscow, Brussels

Orbán is more than the bohunk version of Donald Trump that he is often portrayed as. He is blessed with almost every political gift—brave, shrewd with his enemies and trustworthy with his friends, detail-oriented, hilarious. In the last years of the Cold War, he stuck his neck out further than any young dissident in assailing the Soviet Union. That courage helped land him in the prime minister’s office for the first time in 1998, at age 35. He has a memory for parliamentary minutiae reminiscent of Bill Clinton. At a January press conference, he interrupted a speechifying reporter by saying, “If I’ve counted correctly, that’s six questions,” then answered them in sequence with references to historical per capita income shifts, employment rates, demographic projections, and the like.

His secret weapon, though, is his intellectual curiosity. As Irving Kristol did when he edited the Public Interest in the 1980s, Orbán urges his aides to take one day a week off to devote to their reading and writing. He does so himself, clearing his Thursdays when he can. Raised poor in a small town west of Budapest, preoccupied early by politics, he has had to acquire much of his education on the fly, as a busy adult. His ideas are powerful, raw, and unsettled. Orbán has changed his mind about a lot of things—unregulated free markets above all. Out of a regime of deep reading and disputation come his larger theories about the direction of Western civilization, and many people probably find voting for Orbán satisfying in the way that reading Jared Diamond or Yuval Noah Hariri is satisfying. Orbán believes that Western countries are in decline, and that they are in decline because of “liberalism,” which in his political vocabulary is a slur. He uses the word to describe the contemporary process of creating neutral social structures and a level playing field, usually in the name of rights.

This project of creating neutral institutions has two problems. First, it is destructive, because the bonds of affection out of which communities are built are—by definition—non-neutral. Second, it is a lie, because someone must administer this project, and administration, though advertised as neutral, rarely is. Some must administer over others.

Carried to its logical conclusion, liberalism will, in Orbán’s view, destroy Hungary. “It is not written in the great book of humanity that there must be Hungarians in the world,” he said in his State of the Nation address in February. “It is only written in our hearts—but the world cares nothing for that.” This sense that Hungary might be only one political miscalculation away from extinction is widely shared. There was one country, in the wake of World War I, that was treated more harshly than Germany. The Treaty of Trianon turned a cosmopolitan, advanced central European powerhouse of 20 million people—the Kingdom of Hungary, Budapest’s half of the Austro-Hungarian empire—into a statelet of 8 million and divvied up two thirds of its territory among other nations.

This dismemberment helps explain many of the worst things Hungary did, and had done to it, in the century since. Hitler helped the country recover some of its territories in World War II, but Russia repressed them and then some. The historic heart of Hungary is Transylvania, now on the other side of the Romanian border. Other ethnically Hungarian remnants of the nation are to be found in Serbia, Slovakia, and Ukraine. Orbán is fond of a bitter, Trianon-era joke to the effect that “Hungary is the only country that borders on itself.” It is as a nation of 15 million, and not as a state of 10 million, that most Hungarians understand themselves, and Orbán has done nothing to bring them to a more liberal understanding.

Hungary’s most acute present-day problems are partly the result of its four decades under Communism, including the Soviet Union’s bloody suppression of its 1956 uprising. But, like contemporary Russia, the country suffers just as much from the excess of faith it placed in Western expertise during its botched transition out of Communism. One of Orbán’s mentors recalls: “We were all liberals then,” using the term “liberal” to mean believers in markets. But about markets Hungarians had more enthusiasm than expertise. They sold off their best state-owned businesses to foreigners, and saw others taken over by savvy ex-members of the Communist nomenklatura, who knew where value lay hidden. “It was a trap,” says one of Orbán’s younger advisers. “To open markets with no capital. Now we are trying to get out of that trap.”

For a Soviet satellite, Hungary had been advanced. The 1956 uprising had scared the Soviets. They allowed János Kádár, the strongman who bottled up Hungarian dissent until the Reagan Administration, to borrow hard currency from the West. Budapest had its first Hilton in 1977. It soon had lots of debt, too. By the time the Berlin Wall fell the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio hovered around 75%, a figure then considered beyond reckless but today about average for Western economies. Things got worse when the Wall came down. GDP fell 20% between 1988 and 1993. There were suddenly hundreds of thousands of unemployed in a country that, under Communism, had had full employment. Hungary’s population of gypsies, or Roma, had never been a perfect fit in society but now many came unstuck from their jobs and homes.

A nostalgia for Kádár arose that has not fully dissipated. Between 1994 and 1998 the supposedly free-market heirs to the anti-Communist dissidents ruled in coalition with former Communists. Orbán took office in their wake, ran a responsible, lean, relatively patronage-free government for four years…and was bounced from office in 2002. That taught him a lesson. The years 2002-10 saw the full restoration to power of those who in the 1980s had been trained as the next generation of Communist elites, dominated by the Socialist multimillionaire Ferenc Gyurcsány. Penury and soaring unemployment marked the time. In 2006, Gyurcsány was captured on tape at a party congress explaining that “we lied, morning, noon and night” to stay in power. Protests arose. Police repressed them violently. Orbán’s detractors rarely mention any of this when they complain about the lack of an alternative to him. For most Hungarians, 2006 is the alternative.

Orbán returned to power in 2010 with a large enough majority in the National Assembly (two thirds) to rewrite the constitution from scratch. He and his party Fidesz did so, in what he would provocatively call an “illiberal” way: setting Christianity at the middle of Hungarian life, declaring marriage to be between a man and a woman, banning genetically modified organisms. On top of that, Orbán was re-elected with two-thirds majorities in both 2014 and 2018, enabling him to fine-tune these arrangements, and add more, as he saw fit.

Economic Turnaround

Orbán was happy to pick fights with liberal rule-makers in the realm of politics. But he saw that, in an era of fast-moving international finance and pitiless debt markets, tiny, poor Hungary could challenge the global economy’s liberal rule-makers only with extreme caution. “You must stay economically successful,” he warned in that 2015 Kötcse speech, “because in the modern spirit of the age, even if you are right, or closest to a morally perfect position, if you are not economically successful you will be trampled underfoot.”

It was two years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers when Orbán got power back, with the crisis over the Euro and Greece’s state finances at its height. His lightning-fast restoration of Hungary’s financial credibility and economic performance is, even today, a foundation of his credibility and popularity. For Hungary was in a very similar position to Greece: heavily indebted, with 12% unemployment and an economy that had shrunk by 6.6% in the previous year. Having acceded to the European Union under a disciplinary “excessive deficit procedure” in 2004, it risked becoming a permanent ward of continental regulators and the International Monetary Fund. When these authorities pressured Orbán to accept an austerity program like the one they were then devising for Greece—raising taxes and cutting services in order to pay off international banks—he refused.

Instead, working with his bold economics minister György Matolcsy, he pursued policies decried at the time as radical and irresponsible. He raised the minimum wage. He cut personal income tax rates sharply, from 30% to a flat rate of 16% (they would fall further, and corporate rates would bottom out at 9%, the lowest in Europe). He made up for those cuts by introducing special sectorial taxes on companies that had emerged from the financial crisis intact, and had even profited from it—mostly foreign banks, energy companies, and retailers. He “nationalized” pension funds—although this was more a bookkeeping arrangement than the radical program it was often presented as. And he averted a foreclosure catastrophe by convincing banks to accept payment in Hungarian forints for loans that Hungarian homeowners had taken out in Euros and Swiss Francs. He linked welfare to work. He began reclaiming some of the industrial enterprises so gullibly surrendered after the fall of Communism, buying back 21% of the energy giant MOL from Russia in 2011.

There are certainly reasons to worry about the underlying strength of the Hungarian economy. Economist Zoltán Pogátsa of the University of West Hungary notes that the country still gets subsidies from the E.U. that amount to 6% of GDP. But all in all, Orbán’s program, universally denounced as a gamble, was a staggering success. Hungary had repaid its IMF loans in full by 2013. The country now has 4% growth and an unemployment rate of about 3%. Debt has fallen from 85% to 71% of GDP, and labor force participation risen from 55% to around 70%.

Orbán was the first conservative politician to rediscover, after the crash of 2008, that a “strong state” is sometimes needed to attain conservative ends—in this case, avoiding the debt bondage and extinction of sovereignty that were to be Greece’s fate. Of course, this strong state also had the potential to distort Hungarian politics, and permit the government to name winners and losers. Orbán had a soccer stadium built in his hometown of Felcsút. His family grew wealthy. A Felcsút pipe-fitter became a multi-millionaire. His university friend Lajos Simicska became one of the richest men in Hungary. Those cultural and arts posts that it was within the power of the government to confer were given to reliable political loyalists. Complaints arose about the curtailment of press freedom. An Orbán-friendly magnate bought the struggling daily Népszabadság, once the organ of the Communist Party, and shut it down. Dozens of pro-government media outlets were corralled into a foundation called KESMA which, European Union regulators complained, was not subject to ordinary anti-trust rules, and, readers complained, produced uniform news and opinion in outlets across the country.

The novelty of such arrangements, though, has been exaggerated. Most governments in Hungary have filled cultural positions with allies. The practice is common in Italy, too. There was more media diversity than Orbán’s detractors let on. The Luxemburg-based RTL group was the most popular broadcaster in Hungary. There were implacably anti-Orbán sites online, like Index and 444. When Orbán’s friend Simicska broke with him, he used his newspaper Magyar Nemzet to attack Orbán in the most vulgar terms, comparing him to an ejaculation with an acronym (“O1G”) that is now a standard anti-Orbán epithet, one that journalists have used in addressing him at press conferences and clothiers stamp on T-shirts. Simicska bought billboards near the international airport calling Orbán a gangster.

Orbán’s powerful mandate, his two-thirds majority, gave him power to amend the country’s constitution at will. This was not the same thing as authoritarianism—there aren’t a lot of reporters in Beijing likening Xi Jinping to an ejaculation. But the power to reshape a constitution quickly and without dissent will feel like arbitrary power to its opponents, even if the power arises from a democratic majority.

The opposition now turned to denying the legitimacy of the constitution altogether. Whenever thwarted in local political give-and-take, it summoned imperial help from outside the constitutional system: from the European Union and (when Barack Obama was in office) the United States. Last year the Dutch Green-Left party member Judith Sargentini submitted a motion to the E.U. Parliament alleging corruption and the violation of the rights of minorities and migrants. The Parliament condemned him for “a serious breach by Hungary of the values on which the Union is founded.” Orbán saw it differently: There was no clash of values, only of classes. He had kept Hungary from being bullied by bankers, bureaucrats, and other powerful rule-making foreigners. This naturally upset the powerful rule-making foreigners and their allies within Hungary.

A Hungarian Hungary and a European Europe

In an otherwise loosey-goosey age, Orbán’s strong state asked a lot from people. It would be great to exercise the prerogatives Orbán had claimed at his 2015 Kötcse speech. But you could only make such demands if you could rally citizens behind something transcendent: maybe patriotism, national unity, recovered Hungarian grandeur. Orbán made June 4, the anniversary of the Trianon treaty, a Day of National Unity. He made those ethnic Hungarians in other former East Bloc countries eligible to hold Hungarian passports—and vote. Orbán was sending a message to foreigners overwhelmingly likely to support his party, rather like U.S. Democrats relying for their next electoral majority on people who don’t even live here yet.

It was not necessary for ethnic Hungarians to immigrate, though some did. For a Hungarian from Slovakia (an E.U. member), a Hungarian passport was a courtesy. For a Hungarian from Romania (an E.U. member without full freedom of movement), it was a passport into the E.U.’s Schengen zone, granting rights to work not just in Budapest but in London. For a Hungarian from Ukraine it was an invitation into the E.U. Still, since there would not be enough imported Hungarians to man the Hungarian economy, it seemed Hungary would need to do what western European countries had done: open the doors to mass immigration from the Arab world and Africa.

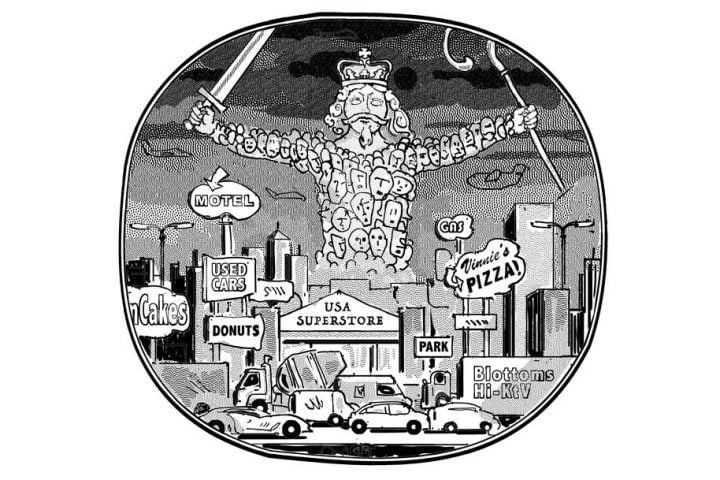

On this, Orbán would not budge. As he saw it, the combination of Anglophone Hungarian businessmen and waves of manual laborers disinclined to learn the beautiful, impossible Magyar language would mean the end of Hungary. Migration from the south, he believed, whether orderly or disorderly, would produce a special kind of country, of the sort that did not exist in western Europe until the most recent decades but which had been the norm in Hungary’s Balkan neighborhood until quite recently—not just in the Habsburg and Romanov empires but also in 20th-century Yugoslavia. Such countries, he told a group of Christian intellectuals in 2017, run the risk of having their culture wiped out:

They will become countries with mixed populations, with a Christian element and a non-Christian element which has a strong religious identity. And if I judge the laws of biology and mathematics correctly, the ratio between these two elements will continuously shift away from Christianity and towards the non-Christian religious communities…. [H]ow this will end is mathematically foreseeable.

Orbán wanted desperately to avoid that. “[W]e want a Hungarian Hungary and a European Europe,” he said. So he sought alternatives to Muslim migration that would allow him to keep Hungary’s full-employment economy from stoking inflation. He has stepped up efforts at reintegrating into the economy the backward but considerably more fecund Roma minority. He has lowered the minimum school-leaving age from 18 to 16. He has remobilized retired people. He has pushed the unemployed onto workfare.

And he has made it possible for the German factories that are the backbone of Hungary’s manufacturing economy to ask for up to 400 hours of paid overtime from their workers annually. So short of labor is Hungary that two strikes in January 2019—one in the 4,000-strong Mercedes plant in Kecskemét, one at the vast Audi plant in Györ, with 13,000 employees—ended with 20% and 18% raises for workers, respectively. In the past year Hungary has (very discreetly) offered residence to Venezuelan refugees of Hungarian background. And Orbán has drawn up a plan offering a $30,000 loan to first-time mothers that gets written off when the mother bears a third child, and grants every woman who raises four children an exemption from income tax for the rest of her life.

At a January press conference Orbán noted that by 2030, in barely a decade, Africa was going to add 448 million people, according to United Nations data—a figure almost identical to the population of the post-Brexit European Union—and that migration pressure would intensify greatly as a result. Under such circumstances the interests of Europe’s immigrant-friendly and immigrant-unfriendly countries were bound to diverge. “In my view,” he said in late March, “everything that serves to stop migration is good, and everything that brings migration here is bad.” Others were just as categorical on the other side. In an unusually passionate speech before the Bundestag days later, Angela Merkel pounded the podium and said that only countries that accepted refugees had the right to influence the E.U.’s policy on migration. Manfred Weber, deputy chairman of Germany’s Christian Social Union (the conservative, Bavarian wing of Merkel’s movement), moved to exclude Orbán from the European People’s Party (EPP), the E.U.’s Christian Democratic umbrella party, and consign him to exile and opprobrium with the rightists and ex-fascists, where Weber believed he belonged.

Liberals in the immigrant-sated western E.U. countries found it bizarre that Hungary (like Poland) opposed immigration despite having very few immigrants by 21st-century measures. Orbán countered that it was perhaps only in low-immigration countries that one any longer had the freedom to oppose immigration. When he spoke with the leaders of western European countries where the migrant population exceeded 10%, they often confided that they were too fearful of rousing inter-ethnic hatred, or losing votes, to broach the subject. “If you’ve had such conversations,” he explained to a roomful of mocking journalists this winter, “you will have heard that they no longer talk about whether or not there should be migration. That is no longer a question for them: that ship has sailed.”

Facing the prospect of a massive influx of population from other continents in the coming decades, the E.U. was, like the United States in the 1850s, a house divided. The high-immigration states of the west could not tolerate the low-immigration states of the east. Orbán hinted that the immigrantlessness of the eastern countries was going to give them a great competitive advantage over the western ones, threatened by terrorism, burdened by welfare, stultified by an official multiculturalism. It was certainly possible to make the opposite argument: perhaps the western part of the E.U. would use cheap, imported labor to set up an economic system that the free-labor countries of the east would not be able to compete with. Either way, it looked like the continent would become all one thing or all the other.

Stopping Soros

One of the strange things about modern political rhetoric is that Viktor Orbán should so often be described as a threat to “democracy,” although his power had been won in free elections. Against this elective power were ranged not one but two oppositions. There was an ordinary electoral opposition contesting arguments within democratic politics. But alongside it was an opposition rooted in activist foundations and ideological lobbies, operating outside of formal democracy but always, it seemed, invoking democracy’s name. Such lobbies are familiar in the United States. It is the American tax code that gave rise to the system in the first place. The very rich can shelter from taxation much of the money they use to influence politics. The American foundation system was multifaceted, innovative, and mighty.

In Hungary the system was new, foreign, disruptive, and associated with one individual: the American currency trader and hedge fund pioneer George Soros. Like the majority of big philanthropists, Soros was on what would be called the political “left.” He funded ads during the Iraq war likening George W. Bush to Hitler, he fought Israeli settlements on the West Bank, he funded gay marriage and transsexual rights. But unlike more mercurial benefactors, Soros had a principle behind his giving, or at least a guru whose writings he could turn to as a guiding inspiration—the Austrian-born British philosopher Karl Popper, whose Plato-focused survey of philosophy, The Open Society and Its Enemies, can be read as a manifesto for liberalism. It is interesting that someone with an intellectual disposition so similar to Orbán’s—a man of action with a yearning towards, and a gift for, abstraction and theorizing that he can never fully live out—should have become his mightiest foe.

Soros founded the Open Society Institute in 1979. Budapest-born and Hungarian-speaking himself, a Jew who had survived the Holocaust, Soros had an interest in central Europe, though not so specifically Hungary. In the 1980s he gave money to the Solidarity movement in Poland and to university scholarships in Hungary—Orbán himself got one, to study at Oxford. In the 1990s, Soros founded Central European University (CEU), which, after provoking hostility and suspicion from a conservative government in Prague, found a home in his native Budapest. CEU was western, accredited in New York state. It was elegant, built into four grand buildings in the heart of Budapest, one of them a factory connected to László Bíró, who in the 1930s invented the ball-point pen. And finally, CEU was highly political, in the sense that it focused on putting the Popper-Soros vision of society into practice, and on training the next generation of political leaders. The “practical” social sciences—gender studies, economics, political science, environmental policy—predominated, not the liberal arts, although there had been a thriving medieval history department there in the 1990s. Most important, CEU was funded on a scale to dominate Hungarian intellectual life, paying its professors more than what those at the long-established universities got.

Soros personified opposition to the nationalist outlook Orbán had wished for in his 2015 Kötcse speech. In the wake of Merkel’s invitation to migrants in 2015 Soros published a plan to bring a million refugees a year to Europe and distribute them rapidly among neighboring countries for settlement. The plan would, Soros wrote, “mobilize the private sector,” but only to run the project, not to pay for it. The funding of it would be done at taxpayer expense, through a €20 billion E.U. bond issue. Orbán published a six-point plan of his own, focused on keeping migrants out. Soros complained that it “subordinates the human rights of asylum-seekers and migrants to the security of borders.” That description was exactly accurate —provided one understands human rights as global philanthropists, political activists, and the United Nations have defined it in recent decades. But there is a competing understanding of human rights in the old law of nations, which makes any right to immigrate dependent on the consent of the receiving nation.

Against the counsel of his advisers, Orbán provoked a clash between the two men and the governing principles each embodied. He passed a “Stop Soros Law” that criminalized offering material support to promote illegal immigration, and banned the sort of refugee resettlements Soros had urged. The government began harassing the CEU by punctiliously enforcing regulations that had heretofore been ignored. As the 2018 election season heated up, anti-Soros ad campaigns began running on billboards and streetcars.

Orbán was very worried about the role of foreign money in his country’s politics. Some have mocked him for this. But obviously, when the most powerful country on earth has just brought its democracy to a standstill for two years in order to investigate $100,000 worth of internet ads bought by a variety of Russians, it is understandable that the leader of a small country might fear the activism of a political foe whose combined personal fortune ($8 billion) and institutional endowment ($19 billion) exceed a sixth of the country’s GDP ($156 billion), especially since international philanthropy is (through the U.S. tax code) effectively subsidized by the American government. An early version of the Stop Soros law proposed taxing foreign philanthropies.

In smaller countries, the political nature of NGOs’ agendas was not as apparent when liberal governments were in power. It became obvious when a nationalist government ruled, and NGOs came to help (or to stand in for) opposition parties, the way the judiciary did in Italy and the United States. The Anglo-Hungarian philosophy professor George Schöpflin, a member of the European Parliament for Fidesz, was mystified by the CEU’s reaction to Orbán’s campaign: “Why did it never appeal against the education law to the Hungarian Constitutional Court?” he asked. But Hungary is not the plane on which such multinational charities usually operate, and for a mere nation to claim jurisdiction might seem presumptuous. The European Union was the real controlling legal authority that charities had to worry about. Over the winter, CEU announced plans to move its headquarters to Vienna, although these plans appear to have been put on hold.

The anti-Soros ad campaign drew accusations of anti-Semitism. Whether those accusations were justified or not is not an easy matter to settle. Reportedly, the ads were dreamed up by the late Arthur Finkelstein, the Reagan-era Republican campaign consultant, long known for personalizing political conflicts. Some were in poor taste. There was one posted on the steps of streetcars so that passengers had to tread on Soros’s face as they climbed aboard. Archetypally, the ads did resemble anti-Semitic campaigns of yore. They showed Soros as a puppet-master, a power behind the scenes. Of course Soros was a power behind the scenes. But Hungary was a country where 565,000 Jews—more than half the Jewish population—had been murdered after the Nazi invasion in May 1944, and a bit more circumspection was expected from its politicians.

The Orbán government, in its four terms in power, had not acted in such a way as to give rise to accusations of bigotry. It had passed a law against Holocaust denial. It had established a Holocaust Memorial Day. It had reopened Jewish cultural sites and refused to cooperate with Jobbik, the leading opposition party, which had a history of anti-Semitic provocations and sometimes commanded 20% of the vote.

The loudest accusations came from western Europe—the very place where, since the turn of the century, in the wake of heavy Muslim immigration, anti-Semitism had risen more sharply than any place on the planet. France in particular had seen a dozen instances of anti-Semitic murder and terrorist violence, all of them perpetrated by the offspring of migrants. Hungary’s 100,000 or so Jews probably had as much to fear from Soros’s plan of open borders as from Orbán’s plan to limit the influence of NGOs.

The anti-Soros ads were effective. They ran during the national political campaign of 2018, were paid for with government funds, and were bolstered by a “national consultation” about immigration that sent tendentious questionnaires to Hungarian households. As this year’s European Union election season began, the campaign got rolling once more. Now the ads showed Soros as the power behind Jean-Claude Juncker, head of the European Commission, and accused the pair of them of favoring illegal immigration. The ad made perfect sense in one way: Juncker did favor continent-wide, rather than national, solutions to Europe’s immigration problem. But it confounded matters in another, because Juncker was a member of Orban’s own European People’s Party. That turned out to be Orbán’s blind spot.

Bringing Orbán to Heel

In mid-March, Manfred Weber came to Budapest to lay down the law to Orbán on behalf of the EPP, of which they were both members. Weber’s Christian Social Union (CSU), once reliably conservative, had lately been abandoned by its base for failing to stop Merkel’s opening of the borders. In the fall the CSU had been clobbered in Bavaria’s state elections, and lost its majority. Weber was running in the May elections to succeed Juncker in the top European post.

Voters in all European countries tend to consider elections to the European parliament a joke. People do not know where the parliament meets (in Strasbourg, officially, though it more often sits in Brussels). They don’t know what the parliament does (its legislative powers are narrowly circumscribed, and its votes can be legally disregarded in many cases). Turnout for its elections is low, as low as 13% in Slovakia. As the sociologist Wolfgang Streeck has written, the E.U. “is so complex that you cannot understand how it works without extensive investigation—and even then you may not quite grasp what it is about.” Orbán’s relationship to the E.U. is just as complex. Hungary is not only among the Union’s most refractory members but also among its top recipients of “structural funds,” transfer payments from the richer countries, used for building infrastructure.

Weber was expected to tell Orbán that he would be kicked out of the party if he did not fulfill three conditions: stop the poster campaign against his fellow party member Juncker, apologize, and let the CEU stay in Budapest.

Why was Weber willing to go out on a limb this way? Why would he risk throwing one of his most loyal party members overboard in the middle of an election campaign? There is a strategic answer to that. Merkel’s 2015 invitation to Middle Eastern migrants had put the EPP in a difficult position. Long the largest party in the E.U. parliament, and the dominant one, it could expect to be much smaller after 2019, since many of its conservatives, horrified by Merkel’s moves, would certainly flee for anti-immigration and nationalist groups. Eventually EPP would have to make coalitions, and it would have two basic choices: reuniting with schismatic nationalists and xenophobes, or seeking out new alliances with liberals and Greens. Most party members favored the latter option, as did Weber, who, in an interview with the hometown Süddeutsche Zeitung, ruled out working with Italy’s firebrand interior minister, Matteo Salvini, whom Orbán described last summer as a “hero.” The party was thus on the verge of repudiating the things that had induced Orbán and Fidesz to join it.

Whatever went on during Orbán and Weber’s discussion, the dénouement was shocking. Weber announced that Orbán’s Fidesz would be suspended from the EPP immediately and indefinitely. This meant it would lose its right to attend meetings, lose its vote on internal matters, and lose its right to nominate officers. A council of “wise men” would scrutinize the behavior of Fidesz to ensure that it upheld democratic norms and determine whether it merited being reinstated. Orbán said he would support the EPP in the coming elections, described the exclusion as a standard procedure that had been used in the past, and chatted cheerily through the press appearance that followed. But it was the most brutal comeuppance of his political career. How had it happened?

In the days leading up to the suspension, Weber’s proposals had taken on a very Bavarian edge. After consultation with Weber, the Technische Universität, located in the Bavarian capital of Munich, had agreed to host part of CEU’s operations, should Weber’s plans to keep CEU in Budapest fall through, and BMW would be a partner, too. It was if the EPP were maneuvering in Weber’s backyard, not Orbán’s.

And, in fact, it was. Whatever one thinks of the justice or injustice of the post-Cold War economic settlement in eastern Europe, the fact is that Hungary’s main role in the global economy is to supply cheap labor for the German auto industry. Thirty percent of Hungary’s foreign trade is with Germany, and Bavaria accounts for half of that. The average German auto worker gets €34 an hour, including benefits, the average Hungarian auto worker €9. You could almost make better money working at a kebab stand in Berlin. But industrial work in eastern Europe is in short and diminishing supply, and those who hold those jobs are grateful to have them.

On top of that, there are ominous rumbles that auto manufacturing is on the way out. Will plants be shut down and Hungarian workers laid off? Will Hungarians be stuck making dirty old cars at declining wages, while German workers, advanced by their powerful unions, get to build the sophisticated, high-value-added electric cars?

Hungary’s position on the border between the powerful economies of Germany and Austria, on the one hand, and some of the poorest parts of the ex-Soviet Empire, on the other, has created a wild demographic upheaval inside the country. You can tell how important the western connection is from the transformation of Sopron, a Hungarian border city from which one can easily commute to Vienna: since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Sopron has more than doubled in size.

The Audi plant at Györ, as noted, is the largest engine factory in the world, the Mercedes plant at Kecskemét is the company’s largest, and the Bosch plant in Miskolc is impressive. But it is the prospect of a new, billion-euro BMW plant, announced for the eastern city of Debrecen last summer, on which Hungarians have pinned all their hopes. Debrecen will be a center not just for assembly but also design and engineering, an economic magic bullet. And as early as last December, the Austrian newspaper Der Standard was urging BMW to put political pressure on Orbán to change his ways. Weber was not laying down the law in the name of Europe. He was laying down the law in the name of Germany—something that has happened often in Hungary’s history, though not for more than three quarters of a century.

The Anglo-American journalist John O’Sullivan, who now heads the Danube Institute in Budapest, put the basic question of Hungarian politics best when he asked: “How will an Orbán government reconcile its resistance to governance by supra-national elites with its considerable dependence on European Union subsidies?” The question can be asked even more broadly. As corporations and political authority grow increasingly intermingled, maneuvering room narrows for politicians like Viktor Orbán. This is the way he sees it himself. “Although we’re convinced that we’re right factually and morally, and that we represent Europe’s interests, perhaps no prime minister and country has ever had a reputation in Western Europe which was as bad as mine and Hungary’s today,” he told a Budapest audience in late March. “Someone must come along with us, because we can hold out for a while, but we cannot hold out forever.”

The period that began at Kötcse in 2015 is now moving towards either a resolution or an escalation, for Hungary and for Europe along with it.