Books Reviewed

One of the most famous sentences in the Churchill canon derives from the moment on Friday, May 10, 1940, when King George VI had just appointed Winston Churchill as prime minister of Britain—the same day that Adolf Hitler had unleashed Blitzkrieg in the West. “I felt as if I were walking with destiny,” he recalled eight years later, “and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.”

On discovering that Larry Arnn, president of Hillsdale College, had entitled his book Churchill’s Trial, I assumed he was referring to that sentence, and so he was, but only in part. Because on finishing it, readers will appreciate that Churchill has been put on trial by revisionist historians of the Right and the Left, and this book is a passionate and profoundly articulate case for the defense, conducted by someone who is in precisely the right apostolic succession from Churchill to mount it.

For Arnn was a research assistant to the late Sir Martin Gilbert (who died last February and to whom this book is dedicated), who himself carried on the writing of the official biography from Randolph Churchill (who died in 1968), who was the only son of Sir Winston Churchill himself. As the editor-in-chief and publisher of Hillsdale’s monumental series The Churchill Documents, expected to run to 23 volumes and comprising pretty much every word that Churchill wrote, Arnn is also in a perfect position to write this hard-hitting and intelligent investigation into what Churchill can still teach us about politics, warfare, and life.

But it is not Arnn’s apostolic position that most equips him to understand Churchill and to help this and later generations understand him. It is the education that Arnn has had and what he has made of it. He was one of the founders of the Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy, because he was and is a student of statesmanship and political philosophy. His approach to the study of politics and philosophy is a self-conscious alternative, and remedy, to the way of studying these great subjects that has been established for a century and more. The established way of studying politics is to begin with the assumption that there is no justice or injustice and no objective distinction between tyranny and freedom or greatness and mediocrity; the established way of pursuing philosophy is to begin with the assumption that there is no truth. It is because he questions both of these conventional views that Arnn is able to understand Churchill as he understood himself and to understand what Churchill might have to teach us. The great gift for us is the powerful reminder that we, too, can and must make momentous choices, that there are better and worse choices to be made, that some of our trials will call for greatness, and that greatness, though rare, is possible.

* * *

Arnn’s thesis in this book is simple. It is that Winston Churchill’s thoughts and actions are of practical use today and contain important insights for us even half a century after his death, and moreover that we are in danger in the present era of ignoring or forgetting them. Critics of Churchill contend—indeed they have even argued at recent meetings of the International Churchill Center—that Churchill’s times were so very different from ours that there are no longer any lessons to be learned from his life and times. They contend that the dangers faced by Western societies are so far removed from those of the 1900-55 period when Churchill was in Parliament that his experiences are strictly for the history books rather than having any relevance to current affairs. Moreover, his chronological and class background as a Victorian imperialist aristocrat renders the story of his life so racially biased and atavistic that he is best swept under the carpet as an embarrassing throwback to a long-dead era.

Arnn is having none of it. On the fraught question of Churchill’s racism, he points out the gaping holes in the conspiracy theory that the wartime premier—fighting to keep the Japanese out of northeast India—somehow welcomed and enabled the terrible Bengal Famine of 1943 that killed millions of Indians. Likewise he points out in the endnotes the occasion on which Churchill asked Mahatma Gandhi’s representative to his country house, Chartwell in Kent, in 1935 and told him that “Mr. Gandhi has gone very high in my esteem since he stood up for the untouchables.” Arnn puts Churchill’s opposition to Indian self-government in its proper historical context, and points out that many of the things Churchill warned of—such as massacres in the Punjab—should India gain independence did indeed come to pass. “In no place did Churchill say that race or color was a qualification for self-government,” Arnn observes, “and he asserted in many places that the Indians were surely capable of it in principle.”

* * *

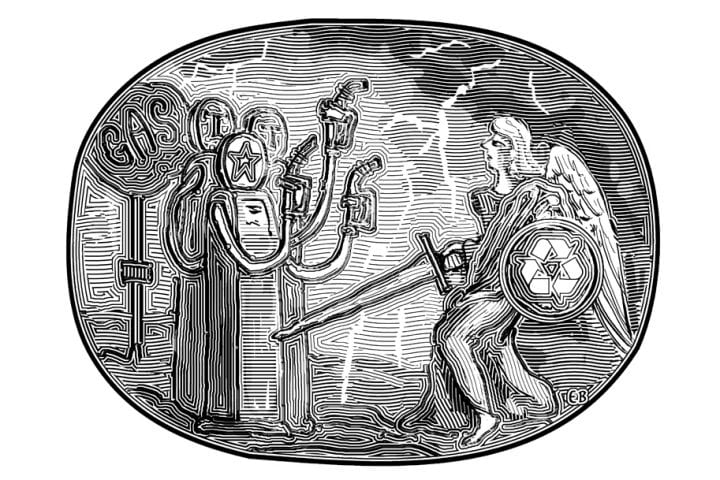

This book has been long in the gestation, and is the result of a lifetime of Arnn’s thinking about Churchill. One of his contentions—which is vigorously contested by the Left and all those who believe in determinism—is that great men and women do matter in history. When one walks around the Hillsdale campus one encounters larger-than-life-sized statues of people like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, Ronald Reagan, and Margaret Thatcher, which eloquently underline in bronze the point the college president is hoping to make in this book: great men and women matter easily as much as “the vast, impersonal forces” of history.

No better example of the validity of the Great Man theory of history can be found in the modern era than in the British cabinet discussions over the question of opening peace negotiations in late May 1940, which is very well covered by Arnn. Several accounts of these vital series of debates within the War Cabinet misrepresent the stance taken by the then-foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, whose biography I wrote in 1991 and who is often wrongly depicted as advocating craven surrender to Hitler’s demands. In fact, the issues at stake and positions taken by the protagonists were much more subtle and complex than that, but ultimately no less perilous, because had peace negotiations begun at the time of Britain’s retreat from the European continent at Dunkirk, there is no telling where they might have ended. Arnn relates these debates with a sure touch, explaining how Churchill’s resolution and political judgment led to “the salvation of free government.”

By total contrast, the Marxist interpretation has absolutely nothing to tell us about the crucial British decision to fight on in 1940. The representatives of the proletariat around the table of five War Cabinet members—Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood of the Labour Party—were virtually silent throughout, while the key discussions took place between the two aristocrats—Halifax and Churchill—with the representative of the bourgeoisie, Neville Chamberlain, also staying pretty quiet. At this vital moment in the history of Western Civilization, the Great Man theory of history explains everything and the Marxist interpretation nothing.

* * *

Further undermining the Marxist analysis and its preoccupation with the idea of historical inevitability, Arnn concentrates on the importance of chance and sheer luck in human events, something of which Churchill himself was deeply conscious. “We have but to let the mind’s eye skim back over the story of nations,” Churchill wrote, “indeed to review the experience of our own small lives, to observe the decisive part which accident and chance play at every moment.” For if history is but the accumulation of the experiences of tens of millions of people making scores of conscious choices each day over millions of years, of course that cannot be trammeled along the set, class-oriented lines laid out by the determinists.

Nor is Arnn having any truck with the modern fashionable theories for the outbreak of World War I that blame other forces than the leadership of Germany and Austria-Hungary for the cataclysm that resulted. For all that historians have sought to blame imperialism, or the arms race, or capitalism, or Anglo-French “arrogance,” or even Churchill’s supposed warmongering for the tragedy of August 1914, this book correctly states that in that climactic month “Germany and Austria let loose their war machines upon Serbia to the south and upon Belgium and France and their allies to the north and west.” Their leaders wanted to strike while they thought time was still on their side, in order to dominate the European continent and thus ultimately the world.

Whereas a large number of Churchill’s biographers tend to ignore or skate over his sole work of fiction, Savrola: A Tale of the Revolution in Laurania (1899), as a mere jeu d’esprit, Arnn rightly spots in it a hint as to Churchill’s charitable and fundamentally decent political philosophy. Churchill, who published it at only age 25, later asked his friends not to read it as he was embarrassed by his youthful excursion into novel-writing, but Arnn sees what he rightly calls this “fiction near to autobiography” as a key to understanding the man who at the time of writing was only months away from entering the House of Commons for the first time.

* * *

Arnn doesn’t shy away from drawing morals and conclusions from Churchill’s writings and making generalizations about human nature that on reflection are both true and worthwhile. “Science is necessary,” he writes in a commentary on one of Churchill’s essays,

and also science is a master. As the human ability to make grows, the human ability to control the engines by which we make diminishes. The logical problem is relentless: we may stay as we are and lead shorter lives of pain and trouble, or we may use our capacity to make our lives easier and safer. If we do that we will gain power, and we can use that power against ourselves.

Such conundrums are found throughout this book, and leave the reader thoughtful.

Another example is to be found in Arnn’s extrapolation of a thought that Churchill expressed in Savrola about how science was replacing civilization and its virtues. “Right has never been simply sovereign over might,” Arnn writes, “but it has been a component of it, and previously a larger component.”

Now what matters is invention and the proper organization of invention into practical power. We see in our day that the application of this growing power becomes easier and requires less in the way of organization. None of the countries from which the 9/11 terrorists hailed could produce a jetliner. But nineteen of their citizens, spending modest amounts and taking a few months of preparation, could destroy the two tallest buildings in the United States, damage the Pentagon, threaten the White House, and kill nearly three thousand people in a few hours’ work.

The book is separated into three distinct sections—War, Empire, and Peace—and the author therefore places Churchill’s imperialism at the center. “Churchill was an imperialist,” he states unambiguously at the start of the second section. This emphasis might make some Americans—whose country sprang from an anti-colonialist struggle, after all—slightly uncomfortable, at a time when the Left has managed to equate imperialism with racism and exploitation. Yet Churchill was indeed a child of the Empire, and it was to that entity, quite as much as to the British nation, that he dedicated his life.

In perhaps the most famous of his wartime speeches, Churchill said in 1940: “Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say ‘This was their finest hour.’” He chose to laud an institution that unbeknownst to him had only 15 years to last, rather than a thousand (though the Commonwealth is still going, and indeed expanding). Churchill could hardly conceive of a Britain without an empire, but was forced to live to see it.

When Churchill sent military aid to Greece in April 1941, a decision that was criticized by some of the chiefs of staff at the time and by military historians ever since, and which ended in disaster, he defended his actions in Parliament in what Arnn describes as “a beautiful statement.” On April 27, 1941, he said of the Greeks:

By solemn guarantee given before the war, Great Britain had promised them her help. They declared they would fight for their native soil even if neither of their neighbours made common cause with them, and even if we left them to their fate. But we could not do that. There are rules against that kind of thing; and to break those rules would be fatal to the honour of the British Empire, without which we could neither hope nor deserve to win this hard war.

Of course Britain had given similar guarantees to Poland before the war, which she signally failed to redeem because of immutable geographical facts—i.e., Germany being in between Britain and Poland—but Churchill felt the honor of the Empire he loved was at stake in 1941 when the Royal Navy could deliver a British army to Greece.

To admire Churchill the defender of democracy yet decry Churchill the imperialist —as President Franklin D. Roosevelt often did—is a false dichotomy, because they are one and the same man who held a certain idea of the British Empire, just as Charles de Gaulle had “a certain idea of France.” Churchill’s idea had nothing to do with one-man-one-vote, but everything to do with protecting the weak (e.g., the untouchables) from economic exploitation and Mughal-level taxation, the subcontinent from Russian, Pashtun, or Japanese incursions, the people from barbaric practices such as thuggee (the murder of travelers) and suttee (the practice of burning wives on their husband’s funeral pyre), and the minority Muslims from the majority Hindus, all the while using the then-incomparable power of the Royal Navy to keep global trading routes open. To reduce such a complex and noble duty, one that Churchill believed in utterly and to which he dedicated his life, to the soulless Marxist theory of imperialism as being all about capitalist dumping of excess production, is completely to misunderstand Britain’s three-centuries-long role.

* * *

A criticism of this book is that far too many of the most fascinating endnotes ought to have been incorporated into the text or appear as footnotes at the bottom of the page. Readers simply don’t refer to the back of the book all the time, especially when the majority of endnotes are page citations, so they will miss a huge number of charming, learned, and occasionally important facts about Churchill and his times. We learn in the endnotes, for example, of Churchill’s Christmas 1929 broadcast appeal for money to buy wireless radios for the blind, in which he said:

If you are rich you can easily afford it. If you are rich enough to send 25 guineas it can be arranged that a number of blind people in your particular district should be specially chosen to have the wireless sets purchased with your money: & if you like—but I expect you wouldn’t—your name can be on every set. If you are not rich—to give something however little is the best way to feel rich.

Churchill believed that Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem Locksley Hall predicted as early as 1835 such phenomena as air power, the League of Nations, and Bolshevism, though frankly that does require a construction being put on six couplets at which most might balk. Arnn is on much stronger ground when he credits Churchill himself with foreseeing developments and inventions far ahead into the future in two essay-length articles that Churchill wrote in 1931 and 1936, which are reproduced in extenso here as appendices. Of course, it was also Churchill who in 1924—long before the Manhattan Project began at Los Alamos—wrote, after a conversation with his scientific advisor Professor Frederick Lindemann, “Might not a bomb no bigger than an orange be found to possess a secret power to destroy a whole block of buildings—nay to concentrate the force of a thousand tons of cordite and blast a township at a stroke?”

* * *

Arnn sets great store by Churchill’s powers of foresight, which he rightly sees as an important attribute in a statesman. In the first of the appendices, an article entitled “Fifty Years Hence,” which first appeared in the Strand magazine in December 1931, Churchill made the essentially Whiggish point that “We assume that progress will be constant…for if it stopped or were reversed, there would be catastrophe of unimaginable horror.” It was a sentence that could only have been written before Ausch-witz. Later on in the article, Churchill avers that “The past no longer enables us even dimly to measure the future.” He went on to imagine something that sounds similar to the internet and broadband when he wrote of how “Wireless telephones and television, following naturally upon their present path of development, would enable their owner to connect up with any room similarly installed, and hear and take part in the conversation” and that “excessively rapid means of communication would be at hand.”

Years before their invention, Churchill wrote about “solar energy,” “synthetic food,” robots, inter-planetary space travel, and nuclear bombs “which can annihilate whole nations.” Yet he predicted that, “Without an equal growth of Mercy, Pity, Peace and Love, Science herself may destroy all that makes human life majestic and tolerable.” It was a doleful view, not least because he felt—even two years before Adolf Hitler came to power—that “Democratic governments drift along the line of least resistance, taking short views, paying their way with sops and doles and smoothing their path with pleasant-sounding platitudes.” If that isn’t a prediction of modern Western foreign policy towards the autocracies of Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea, it’s hard to state what is.

* * *

In august 1936, with Hitler having re-militarized the Rhineland, Churchill wrote an article in Collier’s magazine entitled “What Good’s a Constitution?” which Arnn also reproduces in full. “Does a government exist for the individual,” it asked, “or do individuals exist for the government?” Faced with the rise in the power of the totalitarian states of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Soviet Russia, and Imperial Japan, Churchill’s answer was one that would gladden the heart of any Tea Party supporter today. “In the United States,” he wrote of New Deal America, “economic crisis has led to an extension of the activities of the Executive and to the pillorying, by irresponsible agitators, of certain groups and sections of the population as enemies of the rest.” Was Churchill perhaps thinking of FDR himself, who in his First Inaugural address in March 1933 had spoken of “the rulers of the exchange of mankind’s goods [who] have failed through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence” and “unscrupulous money-changers [who] stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men,” and generally attacked what he called “a generation of self-seekers”? By total contrast, Churchill offered an analysis that would appeal to any modern-day libertarian. “It is when passions and cupidities are thus unleashed,” he wrote, “that the handcuffs can be slipped upon the citizens and they can be brought into entire subjugation to the executive government.” Instead, Churchill believed, “The true right and power rest in the individual.”

In one of the few areas where Larry Arnn takes serious issue with Churchill—over whether “The past no longer enables us even dimly to measure the future”—readers of this intelligent, thought-provoking, and well-written book will conclude that the president of Hillsdale is right and the prime minister of Great Britain was wrong. The past is in fact the only sure way by which we can measure both the present and the future, and it is books like this that will help us do it. Readers might also conclude that, by the standards set by Winston Churchill as interpreted by Larry Arnn, we are doing woefully badly in The Age of Obama or Trump. Whatever we conclude about that, however, as jurors at Churchill’s trial, the evidence and testimony of this book will persuade readers that Churchill’s accusers have shown a knowing and reckless disregard for the truth.