Books Reviewed

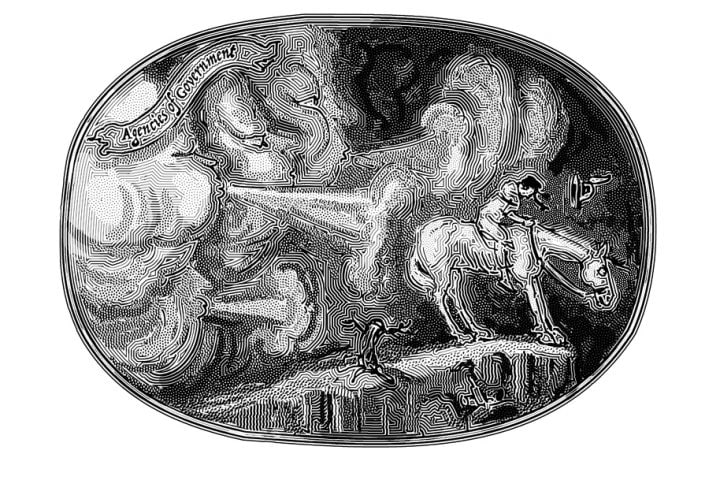

You didn’t build that.” In 2012 President Obama directed these words at entrepreneurs, those with “a business.” The president explained that “somebody else made that [business] happen.” Specifically, “somebody invested in roads and bridges.”

These are the key elements of our “crumbling infrastructure,” as it is routinely labeled in public-policy debates. Who built our infrastructure? You didn’t. Government did.

John Tamny’s Who Needs the Fed? is mainly a book about how credit-strapped entrepreneurs nevertheless succeed. But now and again it is about failure, a government specialty. Consider roads and bridges. In the big coastal cities, Tamny notes, commuters endure about 80 hours per year, or two workweeks, in rush-hour congestion. We rage against traffic tie-ups, to be sure, and they have kept afloat an old-tech business in the form of terrestrial radio, but somehow we do not immediately think big, imagine that the whole mess could go away, and then set to getting it done. We don’t build that.

* * *

Why not? Because government discourages and distracts us from the business of solving problems. Capitalists, Tamny writes, “grow rich by turning that which is obscure and expensive into that which is ubiquitous and cheap.”

What if governments got out of roadbuilding altogether? Logic dictates that the traffic gridlock we despise would soon enough disappear as entrepreneurs set about experimenting with ways to design roads and road usage to erase the scourge that is traffic.

That such a prospect sounds unrealistic, Tamny suggests, means that we’ve lost sight of the government’s extensive role in thwarting economic innovation and growth. We don’t know what’s possible, economically, until those who foresee possibilities act and bring their projects to fruition. Such people—our stock of potential entrepreneurs—are numerous and raring to go. Given this condition, major life headaches such as traffic jams should not exist perpetually.

Who Needs the Fed? considers the range of ways that government policy affects the economy adversely, but its special attention is reserved for our monetary regime. It lays into the Federal Reserve’s conceit that it can stimulate economic demand by such moves as lowering an interest rate. Tamny explains that by lowering interest rates, economic resources become arranged sub-optimally. People buy houses and move, transplanting the locus of their talents from one place to another for no underlying economic reason. Dead-end businesses like Friendster (a forgotten, hapless Facebook predecessor) become fairer bets for a capital infusion. And ever more resources depart the real economy for hedges of the currency regime, above all oil and gold.

In each case, the resources available to entrepreneurs are diminished, and those that remain are deployed less effectively. Tamny contends that government can do very little to increase the total supply of credit—“access to real economic resources”—but can unintentionally decrease it by weighing in on how it gets allocated. Monetary policy, if not all governmental policy, reduces and scrambles the resources used for real production, for projects that remove “unease from life.”

* * *

The relevance of such observations, made by Ludwig von Mises as early as 1912, stems from the low state of the American economy throughout this new millennium. This nation’s economy—the greatest participant in the Industrial Revolution, which in turn has been the greatest development in economic history—has been on the skids for 17 continuous years. In the era of ballooning government since 2000, the private sector has grown at less than a 2% annual rate. Since the onset of the Great Recession in 2008 nearly 10 million people in their prime working years—any nation’s most valuable economic resource—have dropped out of America’s labor force.

What about the success that still occurs in the American economy, the real stuff that happens despite interference and ennui? It is distinctly more impressive than we might think. As government has discouraged and distorted more of businesses’ endeavors, the burden of economic growth has fallen on an ever-smaller residual of companies dedicated to ministering to the market. Uber’s success at creating a network that connects drivers seeking fares with customers seeking rides is a classic example. Tamny explains that Uber’s surge pricing, though sometimes vilified, compensates drivers for the time they lose and aggravation they experience as a result of traffic congestion. And the way to banish surge pricing is to attack the government road monopoly, the source of the congestion problem.

Tamny is distinctly experienced, a Goldman Sachs veteran and longtime editor of Real Clear Markets who supplements his remarks on Uber with telling, less familiar examples. He cites Texas software entrepreneur Joel Trammell, who has argued that the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act discourages new business owners from taking their firms public. Artificially postponing a startup’s ability to sell tradeable shares to investors not only limits its access to capital, but deprives new firms of the capital marketplace’s innumerable, data-laden signals, which go instead to already established firms. The innovation from new firms we have seen in recent years is therefore especially impressive and remarkable.

How does an entrepreneur even recognize information, much less act on it? A change in the price customers appear to be willing to pay for a product? Maybe—but then again that could be pseudo-information, or “noise,” especially given the Federal Reserve blowouts of recent years, which have destabilized the structure of relative prices domestically and international exchange rates.

* * *

What is information? George Gilder has emerged as the best thinker on this question today, exploring the progress that computer science has made in defining information and applying it to economics. In The Scandal of Money, along with his two other recent books, Knowledge and Power (2013) and The 21st Century Case for Gold (2015), Gilder details how recent intellectual history concerning technology vindicates gold, and its cognates in the cyber-realm such as Bitcoin, as the necessary money of any future era of economic expansion and innovation.

Gilder has been a mainstay in political-economic discussion since the 1960s, when as a periodical editor, and a speechwriter for Nelson Rockefeller and Richard Nixon, he responded to the Ripon Society’s call for “fiery moderates” to emerge among Republican politicians and thinkers. In 1981, his bestselling book Wealth and Poverty revealed that he was no moderate in one crucial respect: he felt that left free of governmental interference, the American economy could make boundless achievements. President Ronald Reagan quoted him dozens of times.

In the 1990s, Gilder lionized the technological revolution, his investment newsletter moving markets. His trilogy ending with The Scandal of Money indicates that in the 2000s, Gilder’s attentions have moved from the practical entrepreneurial expressions of the technological revolution to its philosophical implications for all aspects of the economy, not only those having to do with technology itself.

* * *

The three central figures in The Scandal of Money—the logician Kurt Gödel and computer theoreticians Alan Turing and Claude Shannon, each of whom was at work during the middle decades of the last century—did not concern themselves with economics. But Gilder finds their scientific insights crucial to grounding our monetary system today. In 1931 Gödel presented his “incompleteness theorem,” stipulating that no system, even arithmetic, can be axiomatic. Something outside arithmetic is needed to validate the system’s “inherent” axioms. Turing showed that the most advanced of machines, proto-computers, could only explore ever more extensive reaches of self-referentiality unless supplemented by outside “oracles,” namely human beings capable of assigning value to the mechanized output. In the 1940s, Shannon specified that in order for information to be communicated, the “channels,” or “carriers” of that information—wires, for example—have to minimize the “noise” and “static” that they themselves bring to the process of communication.

Gilder cites the classic justification of the price system—that prices confer information in an economy—and adds that prices can only fulfill this function if their “carrier” is “noiseless” in the fashion sought after in Shannon’s computer science. Given that prices are expressed in money, money must have a stability independent of the prices it communicates, lest it violate Gödel’s theorem. And an outside “oracle” must set how money is measured (after Turing).

* * *

There is, for Gilder, perhaps one form of money that fulfills these criteria: gold. It has proven, over the millennia, to be consistently as difficult to improve means of extracting gold from the earth; it takes the same amount of time to mine new gold, relative to the current stock extant, as ever. This means that any quantity of gold can be expressed in time. Since time cannot be manufactured or hoarded or bartered like economic goods to which we assign prices—since time has a fixity that everything else lacks—to follow Gödel, prices should be in gold. It would be “oracular,” in the Turing sense, for us to use gold as money.

Today, gold is increasingly useless as an economic good, vanishing in dentistry and electronics. To Gilder, this means that gold further qualifies as a Shannon-esque information carrier, in that were gold money, vagaries of consumer taste and desire would decreasingly affect the medium that expresses such vagaries, namely the unit of account of the prices of in-demand goods and services.

Gilder implies that civilization’s genius, in short supply in modern times, but on abundant display in past eras, in using gold as the measure of money has been revealed in the information theory of computer science of our own day. Something is off, over the ages, in the sequence of our use and conception of money. Before we theorized profoundly about information, and thus by extension what prices and money are, gold prevailed as money. When we gained that theoretical knowledge, we got the technological revolution, even as gold was being cashiered in favor of fiat money.

The 21st century, therefore, stands before Gilder as a remarkable opportunity. If we take the step of aligning our monetary system with the profundities at which information theory has arrived, we shall open up the possibility of economic growth on a scale comparable to that of the technological revolution itself. Just as the emphasis on noiseless carriers enabled computing power and dexterity to expand—and expand incredibly—so too would money defined in gold serve as a premise of untold expansion in the scale, variety, and beneficence of goods and services.

Gilder is very friendly toward Bitcoin, seeing its algorithmic “mining”—a term that Bitcoin developers have employed—to mimic the ever-increasing difficulty of extracting a new ounce of gold from the crust of the earth. Moreover, more than gold, Bitcoin has no conceivable economic use outside of being a monetary unit.

* * *

Another scientific term that occurs repeatedly in The Scandal of Money is “entropy”—that disorder, randomness, or “surprise,” as Gilder often puts it, that can come from systems running their natural course. The economy, Gilder contends, is naturally entropic. If we knew what everything should cost, we would not need prices indicating costs. The fact that we need information to get what we need and to do better in life means that the economy is ever new.

Entropy can come off as a scary word, suggestive of things flying apart, but Gilder wishes to reclaim it as the root concept of prosperity, innovation, and discovery. “Information theory,” he writes, “does not espouse chaos or anarchy. Shannon demonstrated that it takes a low-entropy carrier—a predictable channel with no surprises—to bear high entropy messages full of surprising content.” Simple money is necessary for a complex, rewarding, and creative economy. Gilder has shown us that if vanity and presentism are preventing us from returning to a gold standard—if we think that gold is too old-fashioned and dowdy—the very latest in avant-garde technical thought vindicates the monetary system of the ages.