Books Reviewed

Enacted in 1972, Title IX of the 1964 Civil Rights Act banned discrimination on the basis of sex in “any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” The statute’s language, straightforward and seemingly innocuous, extended protections already in place for women under the Civil Rights Act into the educational realm.

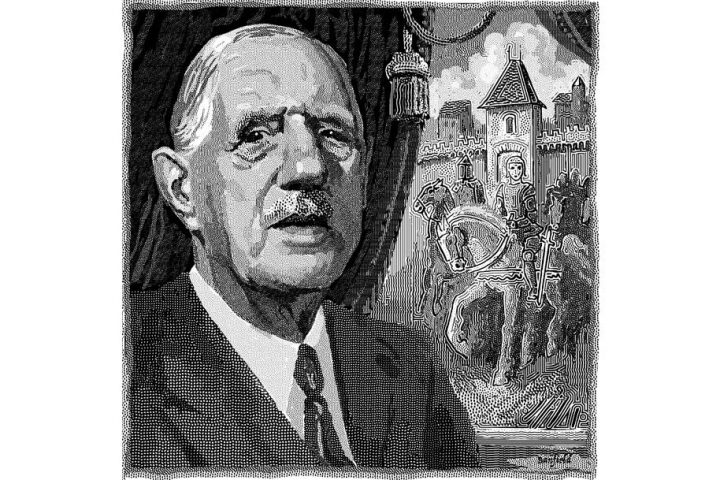

Despite this apparent simplicity, Title IX has spawned a complex, intrusive regulatory regime enforced by a massive public and private administrative apparatus, now holding sway over virtually every aspect of American education. In The Transformation of Title IX, R. Shep Melnick, the Thomas P. O’Neill, Jr., Professor of American Politics at Boston College, explains how we arrived at our present point, mixing detailed chronologies with sophisticated legal and political analysis. It’s a large, complex story. For better and worse, no reader will accuse Melnick of abbreviating or simplifying what happened. For citizens subject to Title IX’s edicts, its twists and turns will surely be downright stupefying. For all that, The Transformation of Title IX should be of great interest to students of the administrative state, and to all concerned with its boundless, unaccountable, and all too often oppressively undemocratic influence over national life.

How did Title IX become the behemoth it is today? The education sector and federal support for schooling on every level grew relentlessly over decades. Congress’s decision to impose Title IX requirements on entire institutions with any publicly funded programs further extended the statute’s reach. The resulting oversight of the massive education establishment spawned a multi-layered administrative apparatus, including various departments within the Department of Education, which came into existence in 1979, and the Justice Department’s increasingly active and powerful Office of Civil Rights. A dense maze of initiatives, policies, lawsuits, investigative settlements, and administrative rules followed, imposing an elaborate and minutely detailed code of conduct, with myriad traps for the unwary, governing every aspect of university life.

* * *

Title IX applies from preschool up to graduate school, but Melnick concentrates on higher education, where its effects have been most profound. The statute’s application to universities unfolded in three distinct stages: a push for parity in college athletics, followed by measures to deal with sexual harassment and assault of women on campus, and, most recently, protections for transgender students.

Initially, bringing “gender parity” to college athletics, the earliest Title IX goal, generated little opposition. Feminist activists who had long envied the lavish funding and alumni enthusiasm for men’s teams needed no convincing. Politicians, parents, and educators were moved by the promise of giving women their fair share of the putative benefits of competitive sports, believed to foster habits, character traits, and connections conducive to later career success. The lack of slots and opportunities for women to play seemed relatively easy to rectify: just create more teams.

That device quickly ran up against an obstacle: men’s greater interest in sports was reflected in participation rates as well as college surveys and questionnaires designed to gauge unmet athletic needs. Conservatives tried, and largely failed, to use these realities to slow official meddling and protect the status quo for men’s programs. Feminists prevailed with strenuous arguments that sexist norms were the root cause of women’s lesser participation and interest in sports.

* * *

Melnick details the universities’ response, which was to embrace what he terms a “field of dreams” philosophy—“build it and they will come.” Judges and government officials got busy crafting a more muscular, albeit shifting and confusing, definition of “parity,” ordering the creation of new women’s teams and the elimination of men’s teams, while seeing fit to meddle in every aspect of women’s sports, even to the point of designating which days their games would be played. Colleges responded by throwing lots of recruitment and scholarship money at female athletes.

Given the levers at universities’ disposal, attracting women to the playing fields proved to be a solvable problem. Melnick describes how the number of women playing varsity sports moved steadily upward, although women’s sports never became as popular and lucrative as men’s. But the supposed benefits for women, nebulous and never convincingly documented, were counterbalanced by real costs, some adumbrated by strenuous critics of men’s college sports mania, such as James Shulman and William Bowen in The Game of Life (2000). Melnick gives ample attention to a cavalcade of problems: women’s distraction from academics, both in high school and college; an epidemic of sport-related injuries and eating disorders; a decline in college enrollment by men, for whom the chance to play is a major draw; and the diversion of college resources from other educational purposes to pay for facilities, coaches, consultants, scholarships, and the competitive recruitment of female athletes. Government investigations proved wildly expensive, imposing multi-million-dollar obligations, set out in lengthy, highly technical documents, on institutions great and small, including the modestly endowed Merrimack College and Quinnipiac University. The need for an ever more elaborate compliance apparatus, and the emergence of rent-seeking constituencies trying to cash in on burgeoning athletic establishments, further drained university coffers.

* * *

The overall result was a decisive transfer of power from private institutions to the government and a relentless increase in educational costs—trends the universities barely resisted, perhaps out of fear of appearing hostile to women’s equality, or just because so much government money was at stake. Melnick cites Vartan Gregorian, president of Brown University from 1989 to 1997, whom he clearly admires, as a singular exception to the wholesale acquiescence, filing a lawsuit to challenge what he viewed as an alarming federal incursion into private institutional prerogatives. His failure to rally support from other prominent universities doomed his efforts.

For all that, athletic parity was a modest project compared to the second Title IX crusade, launched in the 1990s, to purge the campus of unwanted sexual encounters. As proponents soon learned, this far more ambitious project required overseeing all aspects of male-female interaction on campus, including activities that typically occurred unwitnessed behind closed doors. This daunting crusade gave little pause to the government proponents and their feminist cheerleaders, who steamed ahead into this fraught arena. Their efforts came to fruition after 2008. Fueled by social science and data that Melnick admits some have criticized as shoddy and misleading, the Obama Administration declared a “crisis” of sexual assault on campus and vowed to address it aggressively. In a series of “Dear Colleague” letters, the administration commanded schools to act against sexual assault on campus, specifying in detail the procedures both allowed and forbidden.

The results, which Melnick sets out carefully but unsparingly, are now familiar to anyone who follows higher education. He relies on well-documented accounts by critics such as Stuart Taylor and KC Johnson, as well as law professors at Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, and other institutions, to show how federally funded universities (which means almost all of them) began to intrude minutely into every aspect of sexual behavior and to mete out penalties and punishments on the basis of flimsy allegations and proof, using arcane, vague, and sprawling codes of conduct that afforded elaborate protections for accusers (mostly women) and few procedural safeguards for the males accused. He describes how a growing cadre of officials in charge of the process, mostly proponents of the “women as victim” school of thought, investigated, prosecuted, and penalized a steady stream of perceived violations with little meaningful oversight or checks on their power and judgment.

* * *

The final Title IX initiative, just a few years in the making, was a push for transgender rights. Drawing from a 1989 Supreme Court decision suggesting that workplace sex stereotyping could sometimes amount to forbidden sex discrimination, transgender rights activists contended that Title IX requires schools to defer to individuals’ subjective notions of sexual identity rather than give weight to objective biological facts. This boiled down to the requirement that transgender students be allowed access to facilities—such as bathrooms and locker rooms—that match their chosen gender identity.

What lessons can be drawn from these three forays under Title IX? The most important is that ideas have consequences. Melnick’s description of the statute’s trajectory and the vaulting rhetoric deployed by its proponents points to the conclusion that critical to the statue’s application has been the hijacking of its goals and machinery by a radical feminist ideology, according to which, Title IX’s core aim is to achieve equality between men and women. It follows that viewing Title IX as a statute dedicated to equalizing opportunity is mistaken. The true goal has evolved steadily towards achieving equal results, a reordering of all gender relations throughout society, which requires nothing less than a comprehensive remaking of society as a whole.

Melnick rightly identifies legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon as the prime intellectual force behind the seemingly disparate Title IX initiatives. MacKinnon’s influence sheds light on the statute’s evolution from a law designed to provide equal educational opportunity into an all-purpose vehicle for transforming men’s and women’s status, attitudes, and relationships. For MacKinnon, author of Sexual Harassment of Working Women (1979) and Toward a Feminist Theory of the State (1989), and the generation of feminists she influenced, American society is an all-encompassing hierarchical system of male domination, systematically subordinating women, controlling their sexuality, and rendering them powerless. Because all aspects of gender relations and women’s resulting position are deeply tainted by this patriarchy, achieving true equality will require comprehensive and radical reform, with no aspect of gender relations left undisturbed. It follows that stereotypes about women and their “feminine” nature, which attest to their psychological weakness, sexual and physical passivity, and gender-specific interests, must be expunged by all necessary means including the force of law. The goal of remaking gender relations is eminently attainable because the dominant patriarchy, not any biologically influenced inclinations or limitations, sets the possibilities for social life. Gender relations and behavior are entirely “social constructed,” so Title IX can be used to deconstruct and reconstruct them.

* * *

On the sexual assault front, the concept of a “rape culture” follows naturally from MacKinnon’s philosophy, and undergirds the application of that term to campus social life. For MacKinnon and her followers, patriarchal dominance renders sexual relations between men and women inherently coercive, and sexual consent a delusional conceit. Rape is not just an act but a pervasive—and to that extent inescapable—cultural phenomenon. Addressing sexual misconduct is therefore not a matter of banishing a few deviants, but rather of comprehensively revising all aspects of gender relations. As Melnick recognizes, this transformation requires deploying Title IX as an instrument for changing how “students think about sexuality” and reeducating them “on all matters sexual.”

MacKinnon’s view of society also explains the obsession with women as victims, and the one-sided procedures universities have adopted for dealing with harassment complaints. For MacKinnon, there are no genuinely neutral principles and no possibility of fairness towards women at the hands of male-dominated institutions. Due process, procedural safeguards, neutral standards, transparency, objectivity, and the search for truth are covers for men’s power that systematically slight women’s interests. On the radical feminist vision, it makes perfect sense to disregard such principled legal niceties.

MacKinnon’s influence also sheds light on the sometimes contradictory notions Title IX proponents advocate and some female students adopt. Women are simultaneously depicted as addled dupes and noble victims. They are self-deluded weaklings whose attitudes must be forcibly reshaped to egalitarian norms, but also targets of oppression whose narratives and reactions must never be questioned. Feminists were staunchly opposed to using surveys of athletic interest to evaluate Title IX compliance, on the theory that women’s expressed preferences were tainted by pejorative stereotypes. This discounting stands in stark contrast to the deference accorded women’s reports of their own sexual experiences, where the watchword is “believe the victim.” The campus panels that investigate and adjudicate charges of sexual misconduct assign female narratives and feelings absolute authority, preemptively rejecting the possibility that women might sometimes misremember, be self-deluded, or even lie.

In sum, MacKinnon’s version of feminism is a formula for the active management of social life by big government. A society pervasively bedeviled by sexism and the scourge of male domination, and the imperative of vanquishing such domination, fits naturally with a broad, virtually unlimited exercise of government power. The permanent crisis and need for sweeping transformation mandate the creation of a massive bureaucratic apparatus run by feminist “experts,” ideological zealots, and true believers.

* * *

These functionaries have now virtually completed the takeover of our universities. Their victory has created a one-way ratchet of onerous rules. Although the Obama Administration’s heavy-handed sexual assault policies have generated a backlash that is starting to bear fruit, and the Trump administration has withdrawn the Dear Colleague letter mandating the intrusive, biased procedures, many universities have vowed to maintain their current practices. The government has not moved to stop them. Likewise, the Trump Administration’s decision to withdraw the edicts governing transgender access to university facilities has had a negligible effect, with many institutions leaving existing policies in place.

Although the commitments peculiar to radical feminism are critical to understanding the excesses committed in Title IX’s name, there are additional important forces at work, which The Transformation of Title IX often identifies but does not emphasize sufficiently. Melnick, who takes some legally savvy, well-placed shots at executive and judicial overreach, fails to mount a systematic indictment of the statute’s relation to the administrative state. Nor does he draw deeply enough on critiques of modern bureaucracies and the special perversities that afflict ambitious schemes of social regulation developed by such conservative scholars as Philip Hamburger.

Title IX exemplifies the administrative state’s tendency to encroach on powers constitutionally assigned to representatives elected by and accountable to the people. The original sin is a vague and open-ended law, full of “grand phrases with uncertain meaning,” as Melnick puts it. These ambiguities encourage Congress to delegate political responsibility to the judicial and executive branches, which eagerly expand their own authority in the name of protecting “victims.” Melnick describes a process of “leapfrogging,” whereby courts and agencies engage in a competitive collusion, each “taking a step beyond the other” to layer on ever more arcane and meddlesome rules and doctrines. The result is a tangle of obscure, confusing, onerous requirements, set out in hundreds of pages of the Federal Register, agency documents, and court opinions, which control virtually every aspect of how educational institutions function.

* * *

Statutory imprecision also enables officials and judges to ignore procedural checks and substantive limits. Thus liberated, they impose a vision of the statute’s requirements congenial to elite policymakers but not the public. By disingenuously billing their edicts as “interpretive guidance,” or “clarification,” rather than as the rule changes and substantive extensions they actually represent, the Obama Administration extended its grip on American higher education, short-circuiting the democratic safeguards built into the Administrative Procedures Act. Although Melnick admirably strives to be even-handed in describing Title IX’s fate under administrations of both parties, he does not hide his disapproval of these recent excesses, perpetrated by a Democratic administration heavily influenced by female constituencies and activists on the left.

Additionally, a welter of agencies and offices, often with vaguely defined mandates, shares responsibility over the Title IX statute. As Melnick describes it, even the White House was unable, at his request, to put together a comprehensive list of offices and agencies charged with Title IX enforcement. This diffusion of authority makes effective citizen oversight difficult and undermines government accountability. If even the administration doesn’t know who’s in charge, how can ordinary people?

Uncertainty on the judicial front, a product of the open-ended nature of Title IX’s terms, has added to the complexity of the regulatory regime erected to enforce it. “One might think,” declares Melnick, “that after forty-five years most questions about how to interpret Title IX would have been resolved.” To the contrary: continuing uncertainty has freed the courts and agencies to impose ever more elaborate, far-fetched requirements.

Noting the tenuous link between how the statute has been applied and the initial terms and intentions of the law itself, Melnick admits that “[e]ven the reader who has slogged through this entire book will probably have difficulty reproducing those arguments” for much of what has been done in the statute’s name. Quoting Harvard Law professor Jeannie Suk Gersen, he admits that he can’t explain why or how a statute forbidding sex discrimination in educational programs requires restrictions on permissible behavior so stringent that “the difference between sexual violence and ordinary sex becomes harder and harder…to discern.”

* * *

Melnick highlights another egregious example of overreach: requiring universities to defer to students’ subjectively defined gender identity rather than biologically defined categories. Asking why “the wishes of transgender students on these sensitive questions must always prevail and the concerns of other students must be given zero weight,” he finds no answer within the statute, and little useful explication in the case law. He readily admits that the logic of the rule is not only obscure, but a “far cry” from Title IX’s initial meaning and purpose. Yet, despite the glaring flaws, the Obama Office for Civil Rights and several lower courts have not only embraced transgenders’ demands, but extolled transgender complainants as heroic standard bearers of the spirit of Title IX and of the entire civil rights cause.

Needless to say, not everyone views the excesses Melnick identifies as alarming or undesirable. There are powerful forces in place, both within the universities and in society at large, pushing hard for expansive interpretations of Title IX. These include significant portions of the judiciary, not limited to progressives, who regard generous readings of civil rights law as benign or even laudable. Melnick quotes the recently retired federal judge Richard Posner as endorsing wide latitude for courts in this context, with freedom to adopt a “dynamic” theory of judicial interpretation that “updates” the statute’s reach in keeping with “what the last half-century has taught.”

* * *

But what, exactly, has it taught regarding Title IX? Although Melnick never questions the civil rights project overall, he seems genuinely ambivalent about how the statute has come to be applied and is clearly dismayed by its progression from a seemingly simple, well-meaning enactment to a sprawling, heavy-handed, democratically unaccountable enforcement regime. And he is obviously skeptical of initiatives undertaken for the absolutist and often sanctimonious cause of protecting “rights.” Noting wryly that the “arc of history does not stop to recognize hard policy choices,” he takes progressives to task for ignoring Title IX regulatory initiatives’ complex costs and unintended consequences. Melnick’s book is no brief for the present state of Title IX or whitewash of its flaws, but does fail to emphasize the most egregious abuses, especially regarding sexual assault. Many factors have fueled the growing torrent of accusations that has kept the sexual-assault apparatus humming—including the freewheeling hook-up culture, the decline in courtship, a hostility to mainstream masculinity, and the false equivalence of male and female sexuality. But the tilted nature of the sexual assault machinery, and the ill-defined nature of the infractions it deals with and penalizes, have generated a mounting set of casualties, traumatizing college women and afflicting young men whose lives and reputations are marred forever.

And the corresponding benefits? There is no doubt that the law has served as a great engine of government power and growth; a fertile jobs program for an indoctrinated but indifferently educated, predominantly female elite; a money sink for schools; and a surcharge paid by parents in receipt of tuition bills and citizens in receipt of tax bills. It is noteworthy that Melnick’s account is strikingly free of grateful paeans to the law or any sustained demonstration of its benefits. The question he suggests, but never directly asks or answers, is whether Title IX has been worth it. Has it improved the lives of most, many, or some women? Has it helped anyone at all? Or is it possible we’d be better off without it?