Books Reviewed

Seventy years ago it was entirely normal for our most engaged political intellectuals to interrupt their discussions of the Cold War situation in order to write books and essays on, of all things, novels. Three years after co-founding Dissent magazine in 1954, Irving Howe wrote Politics and the Novel, a still insightful study of Stendhal, Hawthorne, Dostoevsky, Conrad, and James. And the chapters in Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination (1950), which include readings of Dreiser, Twain, and Fitzgerald, bore the subtitle Essays on Literature and Society because, he explained many years later, the novel was “an especially useful agent of the moral imagination, as the literary form which most directly reveals to us the complexity, the difficulty, and the interest of life in society.” The novel, to them, was a tradition standing alongside liberalism and Marxism. A political thinker who hadn’t read Moby-Dick was no such thing. Marx himself took a novel, Robinson Crusoe, as a prime specimen of capitalism.

The mid-20th century was a high point for the novel in American society, when novel-reading was “a necessary part of participation in public life…akin to (or, at least, providing the raw material for) serious intellectual analysis of ethics, political theory, and psychology.” Those words come near the beginning of Joseph Bottum’s The Decline of the Novel, which recalls former times when the novel was, indeed, the primary reflection of man and society, the stuff you needed to know if you were to be an informed citizen. The title of his book echoes a classic work of literary criticism, The Rise of the Novel by Ian Watt, which, written in 1957 while the novel was still riding high, could focus on Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding as originators of a genre that looked like it would dominate the Republic of Letters for another 250 years.

We are in a different time. Bottum, former literary editor of the Weekly Standard and poetry editor for First Things, who now directs the Dakota State University Classics Institute, laments that novelists “no longer have the ear of the general culture.” The last time a novel counted as a cultural event, one that a member of the educated class had to register in order to prove his currency, was in 1987 with Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities. No novel published since then has posed a “Cocktail Party Test,” whereby one would be embarrassed to join a gathering of sophisticates without having read it. If anything now plays that role, Bottum says, it is prestige television series such as The Sopranos, Mad Men, or Breaking Bad.

* * *

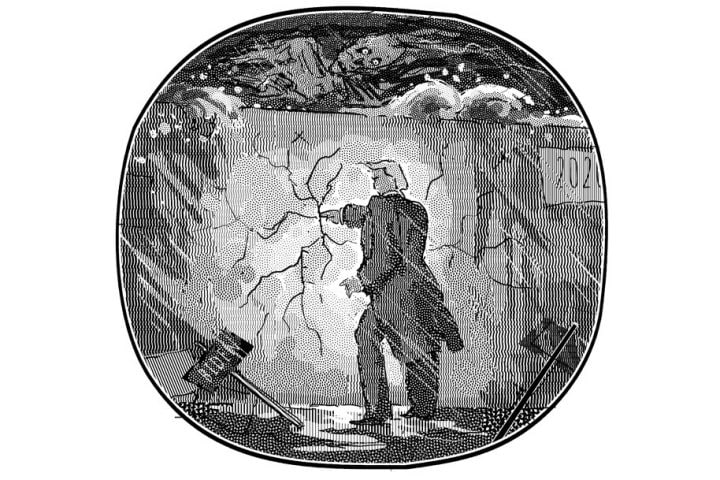

But that doesn’t mean the novel no longer identifies something singularly important in contemporary society. According to Bottum, the very decline of the novel illuminates deep truths about the world. His thesis is this: “The modern novel…came into being to present the Protestant story of the individual soul as it strove to understand its salvation,” that salvation occurring in a world that had lost its divine reverberations. Protestantism highlighted the solitary pilgrim, the lone man facing God without intermediaries. It didn’t animate the world; it left the world to mundane matters (here, Bottum refers to Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism). It deepened the private self, but didn’t stop modernity’s de-spiritualization of external affairs. The novel was the form best equipped to answer this crisis of “the thick inner world of the self” rubbing against an “impoverished outer world.” It could detail social reality in, say, 19th-century mercantile London while probing the evolving “I” of David Copperfield. Technology, bureaucracy, and commerce make up modern life, but they can’t feed hungry souls such as Thomas Mann’s composer Leverkühn in Doctor Faustus and Tom Wolfe’s Charlotte Simmons, the subjects of Chapters 7 and 8 in this book. “In some of its most serious purposes,” Bottum asserts, “the novel as an art form aimed at re-enchantment.”

The decline of the novel, then, demonstrates that such re-enchantment doesn’t work anymore. Reality has grown too material for the novelist to infuse it with meaning. Even as modernity spread and deepened, as long as there was a background of spiritual fate—a lingering ground of Protestant formation—the novelist and his readers could believe in some kind of sanctification of the self in spite of one’s all-too-secular surroundings. But the Protestant churches are now half-empty on Sundays. The cultural mood is disillusionment; reality is “brute facticity.” The novel flourished in a time in which an individual could pass through life in all its quotidian hopes and despairs and still undergo a meaningful progress (or regress). Purpose might be found within a loveless marriage, a dead-end job, or the horrors of war. If the novel doesn’t flourish, we realize, then our era is a purposeless one, and life a random course of ups and downs.

* * *

This is a sweeping theory that recalls older ambitious works such as Watt’s and Georg Lukacs’s The Theory of the Novel (1916), standard references when I was in graduate school in the ’80s. They helped make literary study exciting and momentous before the scolds of political correctness took over. Bottum’s readings of Clarissa, Waverley, David Copperfield, and I Am Charlotte Simmons bear out his theory in masterly judgments and lively prose. One is inclined to take seriously even his whimsical claim that the novel expired in 1988 when a man of superb novelistic talents, Neil Gaiman, wrote a comic book instead, The Sandman. It’s an idea—though we’ll see if Sin City, V for Vendetta, and other graphic novels Bottum mentions last as long as Dickens. How refreshing, though, to read criticism once again that speaks of metaphysical hunger, a meaningless world, wayward souls, and a literary form that tries to make it all better.