“The object of all good literature,” thinks Sue Brown, a chorus girl and a character in P.G. Wodehouse’s novel Summer Lightning, “is to purge the soul of its petty troubles.” Something to it, quite a bit actually, though Céline, Samuel Beckett, Edward Albee, and a number of other modern writers who pass for serious would strenuously have disagreed. The writing of P.G. Wodehouse—the author of some 95 books of fiction and three of memoir, recently republished in a handsome hardbound collection by Everyman’s Library in London and The Overlook Press in New York—was not merely unserious but positively anti-serious, and therein lay much of his considerable charm.

As for that anti-seriousness, who other than Wodehouse would describe a figure in one of his novels by saying that “if he had been a character in a Russian novel, he would have gone and hanged himself in a barn?” Who but Wodehouse could mock the moral tradition of the English novel in a single phrase by writing in a novel of his own of “one of those unfortunate misunderstandings that are so apt to sunder hearts, the sort of thing that Thomas Hardy used to write about?” Who but he, through the creation in his novel Leave it to Psmith of a poet named Ralston McTodd, would find humor in the hopeless obscurity of much modern poetry? Only Wodehouse would have the always-to-be trusted Jeeves instruct Bertie Wooster about Nietzsche: “He is fundamentally unsound, sir.” Or have Bertie disqualify a young woman because after 16 sets of tennis and a round of golf she expected one in the evening “to take an intelligent interest in Freud.” Who but Wodehouse would say about a character whom he clearly doesn’t admire that he “was an earnest young man with political ambitions given, when not slamming [tennis balls] over the net, to reading white papers and studying social conditions”—thus flicking off politics as a time-wasting, if not altogether fatuous, preoccupation. At a lower level of anti-seriousness, Wodehouse amusingly mocked crime fiction, crossword puzzles, and antique collecting.

Giving Life Meaning

Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (1881–1975) was, like Kipling, Saki, Orwell, and Somerset Maugham, a child of the empire, which meant that growing up in England he saw very little of his parents, who were off across the seas tending to the British colonies. The third of four sons, Wodehouse grew up in Hong Kong, where his father served as an imperial magistrate. Between the ages of 3 and 15, his biographer Robert McCrum conjectures in Wodehouse: A Life (2004), he saw his parents little more than a total of six months. Owing to such circumstances, Wodehouse was naturally never close to his family, and was especially distanced from his mother, a woman said to be cold, imperious, and forbidding. If he was cut off from normal family feeling, Wodehouse seems to have made up for it by an ingrained optimism, a sunny disposition, a love of sport, and a powerful imagination for fantasy. From his earliest days, he wanted to be a writer. In his fiction, he created a world that never quite existed but is so amusing as to make one feel it a pity that it didn’t.

Wodehouse’s public-school days, at a place called Dulwich—C.S. Forester went there, as did Raymond Chandler—were perhaps his happiest. McCrum notes that on the status scale Dulwich was neither Eton nor Winchester, but “it offered an excellent education for the sons of the imperial servant.” The young Wodehouse was an exuberant sportsman, and excelled at both rugby and cricket, sports that he followed avidly his life long. As a boy he was an ardent reader of Dickens, Kipling, J.M. Barrie, and Arthur Conan Doyle, and also adored Gilbert and Sullivan. At Dulwich he studied on the classics side, and his own novels and stories are dotted with references to Queen Boudica, the Midians, Thucydides, Marius among the ruins of Carthage, the Gracchi, and others.

When Wodehouse was 19, his father announced that there weren’t sufficient funds to send him to Oxford, where his older brothers had gone. He seems to have taken it in stride. He went instead to work at The Hongkong and Shanghai Bank in London, interning in the Bob Cratchit-like role of lowly clerk. In the evenings he wrote stories and articles and supplied comic bits for newspapers and magazines, and in fairly short order wrote his way out of the bank and into an economically independent freelance life. Writers divide between those who may write well but don’t need to do it and those who find life without meaning if they aren’t writing. Wodehouse was clearly of the latter camp. Over a long career (he died at 93) along with his novels and stories he wrote plays, musicals (collaborating on occasion with Jerome Kern), supplied lyrics for other people’s shows (he wrote the song “Bill” for Showboat and worked with Cole Porter on Anything Goes), and did his stint in Hollywood. He appears always to have thought himself a professional writer rather than a literary artist, with a wide following more important to him than the praise of critics.

For a writer who never aspired to be other than popular, in later life Wodehouse acquired accolades from many writers who easily cleared the high-brow bar, including T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, Evelyn Waugh, Dorothy Parker, Kingsley Amis, Eudora Welty, Lionel Trilling, Bertrand Russell, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Hillaire Belloc called him “the best writer of English now alive,” a handsome tribute seconded by H.L. Mencken. “Temperate admirers of his work,” wrote the English drama critic James Agate, “are non-existent.”

Musical Comedy without the Music

Wodehouse wrote no faulty sentences, and countless ones that, for people who care about the pleasing ordering of words, give unrivalled delight. In his biography McCrum offers the following splendid example, one of hundreds, perhaps thousands, that could be adduced:

In the face of the young man who sat on the terrace of the Hotel Magnifique at Cannes there crept a look of furtive shame, the shifty, hangdog look which announces that an Englishman is about to talk French.

The comic touches that bedizen Wodehouse’s prose are one of its chief delights. A drunken character is described as “brilliantly illuminated.” An overweight baronet “looks forward to a meal that sticks to the ribs and brings beads of perspiration to the forehead.” A woman supposed to marry that same stout gentleman has the uneasy feeling that, so large is he, she might be “committing bigamy.” A minor character “has a small and revolting mustache,” another “is so crooked he sliced bread with a corkscrew.” Wodehouse spun jokes out of clichés. His similes are notably striking. A man known to be unable to keep secrets is likened to “a human collander.” Another character is “as broke as the Ten Commandments.” The brains of the press departments of the movie studios resemble “soup at a cheap restaurant. It is wiser not to stir them.” These similes often arise when least expected: “The drowsy stillness of the afternoon was shattered by what sounded to his strained senses like G.K. Chesterton falling on a sheet of tin.” There is a passing reference to “a politician’s trained verbosity,” a phrase I find handy whenever watching a contemporary politician interviewed on television. Like Jimmy Durante with jokes, so P.G. Wodehouse with arrestingly amusing phrases—he had a million of ’em.

“I believe there are two ways of writing novels,” Wodehouse wrote. “One is mine, making a sort of musical comedy without music and ignoring real life altogether; the other is going right down deep into life, and not giving a damn.” No one would accuse P.G. Wodehouse of ever flirting with realism. His fiction is uniformly preposterous. “I don’t really know anything about writing except farcical comedy,” he wrote to his friend the novelist William Townsend. “A real person in my fiction would stick out like a sore thumb.”

Nobody dies in Wodehouse novels or stories. In his fiction there are no wars, economic depression, sex below the neck, little Sturm and even less Drang, with only satisfyingly happy endings awaiting at the close. English country-house scenes were his favorite milieu. These are populated with aimless young men in spats with names like Stilton Cheesewright, Bingo Little, Tuppy Glossop, and Pongo Twistleton; troublesome young women, terrifying aunts, and eccentric servants; notable props include two-seater roadsters, cigarette holders, monocles, and lots of cocktails.

“Romps” seem to me perhaps the best single word to describe Wodehouse’s novels and stories, yet artfully organized romps. The first task of the writer of fiction is to make the unpredictable plausible. Wodehouse’s own method, going a step further, was to think of something very bizarre and then make it plausible. But given his outlandish characters, the impossible confusions they encounter, the unlikely coincidents that everywhere arise, plausibility never really comes into play; more accurate to say that he made the improbable delectably palatable.

Wodehouse allowed that he wrote his novels as if they were plays. “In writing a novel I always imagine I’m writing for a cast of actors,” he wrote to Townsend in one of the letters printed in Author, Author! (1962), their collected correspondence. “One of the best tips for writing a play, Guy [Bolton, his chief theatrical collaborator] tells me, is ‘Never let them sit down.’” Wodehouse kept his characters in action, and felt the earlier the introduction of dialogue the better, the more, given his dazzling touch for it, the jollier. “But how about my flesh and blood, my Aunt Julia, you ask,” says his character Stanley Ukridge. “No I don’t,” says the story’s narrator. “I’m in the soup,” says Gussie Fink-Nottle. “Up to the thorax,” replies Bertie Wooster.

No Small Achievement

To create one imperishable comic character is no small achievement. Robert McCrum holds that Wodehouse created five: Psmith, Lord Emsworth, Aunt Agatha, Bertie Wooster, and Jeeves. I would add as a sixth the irrepressible Galahad Threepwood, the younger brother of Lord Emsworth, an old boy who, during a relentlessly roguish youth, “apparently never went to bed before he was fifty.”

Ronald Eustace Psmith is a former Etonian, monocled, appallingly fluent, a master of comic hauteur. Clarence, the ninth earl of Emsworth, lord of Blandings Castle, is interested only in gardening and in pigs and is two stages beyond absent-minded, described in Leave It to Psmith as “that amiable and boneheaded peer…a fluffy-minded man” who has “a tiring day trying to keep his top hat balanced on his head.” Aunt Agatha is female tyranny to the highest power, pure menace, a woman “who eats broken bottles and wears barbed-wire close to the skin.” Along with his valet Jeeves, Bertie Wooster—the best known of Wodehouse’s characters and a man self-described as having “half the amount of brain a normal bloke ought to possess”—is a classic instance of the Edwardian knut, those upper-class idlers, often second and third sons, with nothing more pressing on their agendas than choosing their dandaical outfit for the day, meeting Algy for lunch at the club, and avoiding those tradesmen foolish enough to have extended them credit.

As for Jeeves, he, undoubtedly, is Wodehouse’s greatest creation, a man who does not so much enter as flow into rooms, omniscient in his learning, formally correct in his syntax, infallible in his good sense, ingenious at getting his master Bertie Wooster and Bertie’s friends out of misbegotten marriage alliances, entanglements with aunts threatening their inheritances, creating along the way innumerable plots thicker and stickier than carnival taffy. “In the matter of brain and resource,” thinks Bertie of Jeeves, “I don’t believe I have ever met a chappie so supremely like mother made.” Jeeves, who recognizes that his master is “of negligible intelligence,” notes that “in an employer brains are not desirable.” Not for comedy they certainly aren’t.

Wodehouse’s fiction does not abound in sympathetic female characters. He was himself not so much misogynistic, McCrum rightly points out, as gynophobic. Whether bluestockings or ditzy airheads, women in Wodehouse tend to be objects of terror, interfering, dangerous in their potential to undermine the knut way of life. Madeline Bassett—with whom the prospect of a marital connection sends Bertie into shivers—is one of these women who, though of attractive exterior, is on the “point of talking baby talk…the sort of girl who puts her hands over a husband’s eyes, as he is crawling in to breakfast with a morning head, and says: ‘Guess who?’” Aunts—there are no mothers I have encountered in Wodehouse—are “all alike. Sooner or later out comes the cloven hoof.” When Bertie remarks that he had “no idea that small girls were such demons,” Jeeves laconically replies: “More deadly than the male, sir.” Galahad Threepwood notes that “the one thing a man with a cold in his head must avoid is a woman’s touch.” Stanley Ukridge remarks that “women have their merits, of course, but if you are to live the good life, you don’t want them around the house.” None of Wodehouse’s heroes is married.

Family and Fiasco

Wodehouse himself married, at 33, to Ethel Wayman, an actress twice-widowed with a ten-year-old daughter. The marriage appears to have been an untroubled one, owing chiefly to each of its partners allowing the other to go off on his or her own. In Ethel Wodehouse’s case, this seems to have been chiefly to go off shopping, mild forms of social lion-hunting, and acquiring expensive places for her family to live. In Wodehouse’s, it meant being left alone to write, with time off for lengthy walks with one or another of the couple’s many Pekingese. They had no children together, but Wodehouse came to love his stepdaughter, Leonora, to whom he dedicated one of his books: “To Leonora without whose never failing sympathy and encouragement this book would have been finished in half the time.” She was the closest he came to having a true confidant and her death at 40 was a great loss to him.

Life generally, though, was good. Wodehouse’s high productivity paid off amply in what Bertie Wooster would call doubloons or pieces of eight. In London he and Ethel lived in Mayfair. They had a butler, cook, maids, footmen, two secretaries, and a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce. He had become, in Robert McCrum’s phrase, “seriously rich.” Praise for his writing, meanwhile, flowed in, with only occasional demurrers. In 1939 Oxford, the university he wasn’t allowed to attend for want of funds, presented him with an honorary degree. Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was on what looked like a life-long roll.

And then the roof, walls, and floor along with it, caved in. The onset of World War II found Wodehouse and his family living in Le Tourquet, in northern France near the English Channel, and when the Nazis marched in, Wodehouse, who didn’t flee in time, found himself interned. At first the internment turned out to be more an inconvenience than anything else, and he was even able to complete a novel during it. Soon, though, the Nazis learned of his fame and, gauging the propaganda value of their prisoner, encouraged him through subtle suasion to recount the relative mildness of his detainment in a series of five radio talks, which he gave in the summer of 1941.

The talks were innocuous enough, though it was a grave mistake for the politically naïve Wodehouse to have made them. Doing so over Nazi radio put him in company with such genuine traitors as William Joyce, known as Lord Haw-Haw and hanged by the English for treason after the war. He also published in the Saturday Evening Post an article, under the title “My War with Germany,” in which, in his extreme naïveté, he remarked that he was unable to work up any hostility toward the enemy: “Just when I’m about to feel belligerent about some country I meet a decent sort of chap” from that country, he wrote, causing him to lose “any fighting feelings or thoughts.” Wodehouse, in other words, used the occasion of the most murderous events in modern history for light laughs.

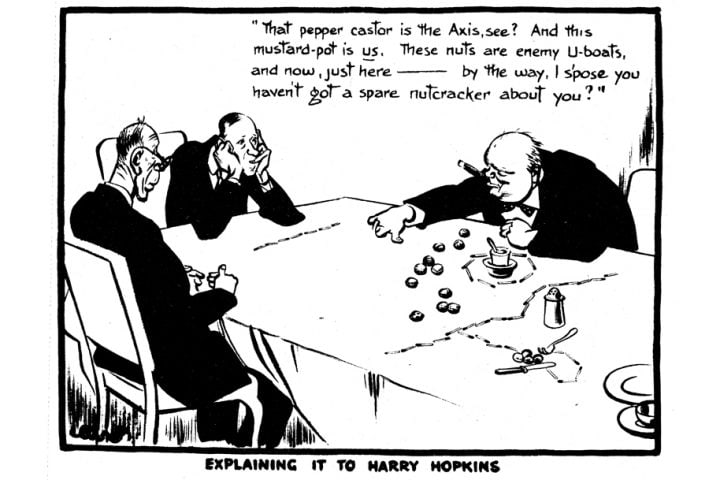

The reaction was swift and crushing. Anthony Eden, in Parliament, accused Wodehouse of lending “his services to the German war propaganda machine.” Duff Cooper, Churchill’s minister of information, held Wodehouse’s behavior to be traitorous. A general piling on was not long in coming. Harold Nicolson refused to believe in Wodehouse’s innocence being the cause for his betrayal. A Daily Mirror columnist named Cassandra, whose real name was William O’Connor, gave a talk over the BBC that began: “I have come to tell you tonight of the story of a rich man [Wodehouse] trying to make his last and greatest sale—that of his own country,” and went on to compare him to Judas. The playwright Seán O’Casey called Wodehouse “English Literature’s performing flea.” Oxford was said to be considering reclaiming his honorary degree. Deep readers began finding evidence of fascism in his books, which were banned from some provincial libraries and in a few places even burned. Songs to which he had written the lyrics were not allowed over the BBC. There was talk about Wodehouse being hanged as a traitor.

Wodehouse called his own conduct “a loony thing to do”; later he would say it was “insane.” Yet it is far from clear that he truly grasped the gravity of his mistake. Malcolm Muggeridge, who later became his friend, thought Wodehouse had a “temperament that unfits him to be a good citizen in the ideological mid-twentieth century.” The best defense of Wodehouse, made by George Orwell in 1945, just after the war was over, was that he was not only a political naïf, but gave his talks for the Nazis at precisely the wrong time: the summer of 1941, as Orwell wrote, “at just that moment when the war reached its desperate phase.” Orwell ends his defense of Wodehouse by writing “in the desperate circumstances of the time it was excusable to be angry at what Wodehouse did, but to go on denouncing him three or four years later—and more, to let an impression remain that he acted with conscious treachery—is not excusable.”

Yet decades passed before Wodehouse was finally forgiven this contretemps. In 1947 he moved, permanently, to America, and in 1955 took up American citizenship. His friend the humorist Frank Sullivan said his doing so made up “for our loss of T.S. Eliot and Henry James combined,” an amusing touch of hyperbole. His wartime broadcasts continued to haunt him, though he claimed to be without self-pity. “I made an ass of myself,” he wrote to William Townsend, “and must pay the penalty.” Still, he was as productive as ever, producing a book a year. At his 80th birthday, in a newspaper ad for one of his books, a literary all-star cast that included W.H. Auden, Ivy Compton-Burnett, Graham Greene, Rebecca West, and others signed on to pay tribute to him as “an inimitable international institution and a master humorist.” Wodehouse wrote to his old friend Guy Bolton: “I seem to have become the Grand Old Man of English Literature.” In 1975 he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth, who was among his most ardent readers, which formally closed the book on his wartime fiasco.

A Happy Indulgence

For the better part of the past two months I have been reading P.G. Wodehouse early mornings, with tea and toast and unslaked pleasure. Although I haven’t made a serious dent in his 95-book oeuvre, before long, I tell myself, I must cease and desist from this happy indulgence, this sweet disease which one of his readers called “P.G.-osis.” “You can,” says a character in an Isaac Bashevis Singer story, “have too much even of kreplach.” (Something of a literary puritan, I feel I ought to add that during these past months I have followed up each morning’s reading of Wodehouse with four or five pages of Aristotle’s Rhetoric and his Nicomachean Ethics—an intellectual antidote, a breath mint of seriousness, you might say.) In a 1961 talk on Wodehouse over the BBC, Evelyn Waugh ended by saying: “Mr. Wodehouse’s world can never stale. He will continue to release future generations from captivity that may be more irksome than our own. He has made a world for us to live in and delight in.”

The work of humorists is not usually long-lived. Among Americans, two very different examples, James Thurber and S.J. Perelman, seem to have bitten the dust, at least they have for me. Yet Wodehouse remains readable and immensely enjoyable. Perhaps this is owing to his having written about a world that never really existed, so that his work, unlike Thurber and Perelman’s, isn’t finally time-bound. “I’m all for strewing a little happiness as I go by,” Wodehouse wrote to William Townsend, and he did so in ample measure. He would have been pleased to learn that for his readers the gift of that happiness has yet to stop giving.