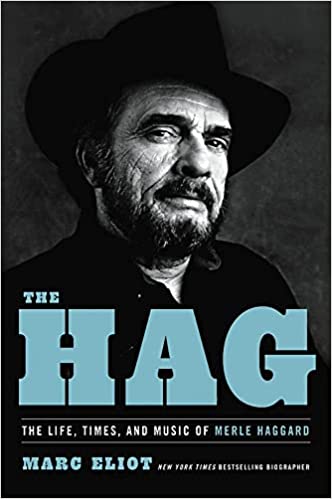

Books Reviewed

Compared to his music, the details of country singer Merle Haggard’s life—his dealings with record companies, the lengths and locations of his tours, the comings and goings of his bandmembers, girlfriends, and wives—are of little interest. Indeed, it is the rare artist’s biography that reads like a novel and doesn’t make one wish for an abridgement. In the field of popular music, Peter Guralnick’s Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley (1994) comes to mind. Marc Eliot’s The Hag doesn’t rise to that level. But it is thorough, workmanlike, and contains many valuable insights about Haggard’s distinctively American working-man blues.

Haggard’s origins informed his music. His parents traveled from Oklahoma to California during the Great Depression along Route 66—the “ghost road of the Okies”—settling near the Kern River on the poor side of Oildale, three miles from Bakersfield. Merle was born two years later, in 1937, and was raised in an old train car (now on display at the Kern County Museum) that his father converted into a home. At age 11, two years after his father’s death, he hopped a freight train in his first attempt to run away, making it 100 miles to Fresno before being nabbed. Three years later, train-hopping having become habitual, he landed in reform school. After that, he progressed to robbery and assault.

***

As Merle turned 18, the “Bakersfield sound”—described by Eliot as “the San Joaquin Valley’s soundtrack for the working man’s unerring belief in the American dream”—was becoming known nationally, and Merle was making a name around town as an employable guitar player. But neither his affinity for music nor his Church of Christ upbringing slowed his descent into crime, and after being locked up nearly 20 times—years later, seeing the film Cool Hand Luke, he said it “seemed like a documentary of my young life”—he was sent to San Quentin State Prison, where he would be confined for two years and nine months.

Merle would never achieve anything close to saintliness in his life, but two experiences toward the end of his prison term propelled him to pursue a non-criminal career. One was developing a friendship of sorts with Caryl Chessman—a then-famous resident of San Quentin’s death row—shortly before Chessman went to the gas chamber. The two never met face to face, but they conversed daily for a time through air vents. Chessman’s criminal beginnings mirrored Merle’s, and he counseled the younger man against coming to the same wasteful end. Merle would later say that Chessman’s execution “scared [him] to death”—and in 1967, he wrote and recorded “Sing Me Back Home,” the story of a prisoner being led to his execution who asks a guitar-playing friend along the way to sing a gospel song.

Merle’s second life-changing prison experience is better known: on New Year’s Day in 1960, ten months before his release, he was in the audience when Johnny Cash—another country star famous for favoring the downtrodden and having plenty of reasons himself to seek redemption—performed at San Quentin.

On his release, Merle took a job digging utility trenches by day and performed in Bakersfield’s clubs by night. He was “discovered” in 1962, recorded his first hit in 1963, and was signed by Capitol Records in 1964. Guided by the invisible hand—he determined quickly that he could make a lot more money in the music biz writing his own songs—he found his calling. Between 1964 and his death in 2016, he would write or co-write 250 of the more than 600 songs he recorded, including 26 of his 38 No. 1 Billboard hits.

***

Several of his early songs were autobiographical. One of the best was “Branded Man,” the lament of an ex-con who can’t outrun the taint of his past—“if I live to be 100,” he cries, “I’ll never clear my name.” Merle kept his criminal past private until 1969, when Johnny Cash convinced him to talk about it during an appearance on Cash’s TV variety show. In 1971, Merle himself performed at San Quentin. And in 1972, California Governor Ronald Reagan issued him a full pardon. One might think that, 12 years out of prison, a pardon wouldn’t mean much to a rich man at the top of the music world. But that would assume that the shame expressed in “Branded Man” had been less than heartfelt. In fact, Merle was overwhelmed with gratitude. The pardon changed his life, he said—it “gave me a second chance.”

Merle gained admirers outside the country music world. In 1968, Rolling Stone published a five-star review of his album Mama Tried. That same year Gram Parsons, the godfather of country rock, insisted that the Byrds include Merle’s “Life in Prison” on their groundbreaking Sweetheart of the Rodeo album. Even the Grateful Dead worked Merle’s songs into their concert repertoire. Yet unlike many other country stars of his generation—including Buck Owens, the progenitor of the Bakersfield sound—Merle never “crossed over” to achieve pop music stardom. Many think this is because he weighed in on the wrong side of the nascent culture war in the late 1960s with his songs “Okie from Muskogee” (“We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street”) and “The Fightin’ Side of Me” (“When you’re running down my country, hoss…”). A simpler explanation is that Merle had no regard for pop music, or even for much of what came to pass for country music in the 1970s. He was “visibly angered,” Eliot notes, when Australian pop star Olivia Newton-John was embraced by Nashville’s business moguls and chosen as the Female Entertainer of the Year by the Country Music Association in 1974. “Anyone who wins the biggest award in country music,” Merle grumbled, “should know who Hank Williams is.”

“Merle always revered the past and respected the dead,” Eliot writes. His friend Frank Mull called him “Professor Haggard” for his penchant, in concerts and interviews, for offering instruction about his musical forebears. “He especially loved to teach younger audiences” about those he most respected, Mull recalled, citing Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills—the latter of whom Merle, as a young boy, once stood on his bicycle to watch through a dance hall window.

***

During Rodgers’s life and Wills’s early career, country music was called “hillbilly music.” The moniker was not meant endearingly, as Martha Bayles points out in Hole in Our Soul: The Loss of Beauty and Meaning in American Popular Music (1994): “the mentality behind [calling it that],” she writes, “is reflected in Variety’s 1926 comment that ‘hillbillies have the intelligence of morons.’” It was not until the late 1940s, when cowboy music became popular, that “country and western” replaced “hillbilly.” Merle rose to fame after the change occurred, but he never lost his sense of connection to the hillbillies—or clingers or deplorables, as they are called today—to whom he was born and with whom he lived much of his life.

Merle’s one attempt to live in Nashville—Music City USA—was miserable and short-lived. Even when he was suffering with cancer late in life, he insisted on having surgery and receiving treatment in Bakersfield Memorial Hospital rather than at the Mayo Clinic or Cedars-Sinai. And if you listen to his later and lesser-known albums, you get the sense that he was growing even closer to his roots. “I won’t be a slave, and I won’t be a prisoner / I’m just a nephew to today’s Uncle Sam,” he sings in “I Am What I Am” to a simple acoustic guitar accompaniment in 2010. “I believe Jesus is God, and a pig is just ham / I’m just a seeker, I’m just a sinner / I’ll be what I am.”

Classically-trained music critic Henry Pleasants, in The Great American Popular Singers (1974), writes of being bowled over upon first listening to Jimmie Rodgers: “This is not just a man speaking or singing,” he recalls thinking. “It’s a whole countryside, an entire people….” Pleasants mistakenly identifies these people as exclusively Southern—the Haggard family is one of far too many exceptions to permit the rule—but more accurately describes them as working people to whom money, advancement, and hope come hard. Journalist Dana Jennings, in Sing Me Back Home (2008)—a memoir about growing up poor and listening to country music in rural New Hampshire—similarly describes country music during its first half century as “music meant for those who’d been bypassed by the American Dream.” It was also meant, of course, for those who could afford to buy records and concert tickets. But it was certainly music that never lost touch with the hobo, the subsistence farmer, and the factory worker. If you doubt it, listen to Merle’s “Big City,” “Mama’s Hungry Eyes,” “Workin’ Man Blues,” “Under the Bridge,” and “If We Make It Through December.”

***

Country music people also tend to be patriotic. Eliot recounts a 1981 New York Times interview in which Merle tied the rising popularity of country music to a resurgence of patriotism. “Every time patriotism comes to the surface, you’ll find country music,” Merle said. He also tied it “to the growing conservative political movement that…put Ronald Reagan in the White House,” even though Merle was not what would be described today as a “Reagan conservative.” In 2003, he publicly defended the Dixie Chicks when they were banished from country radio for criticizing the Iraq War. Two years later, anticipating the MAGA movement by a decade, he wrote and recorded “America First”— “Let’s get out of Iraq and get back on the track / And let’s rebuild America first.” Even “Okie from Muskogee,” he would say, was not meant to defend the Vietnam war but rather the troops fighting the war. He often introduced it in concerts by saying, “Here’s a song I wrote about my dad.”

More than once in the book, Eliot compares Merle Haggard to Robert Frost. He goes too far in suggesting that Merle “might have been recognized as a poet of the first rank if he had written and spoken his words instead of singing them.” On the written page, Merle can’t hold a candle to Frost. But add his music and voice into the mix and you can see Eliot’s point. Listen to “Daddy Frank,” “Twinkle Twinkle Lucky Star,” “Are the Good Times Really Over,” “Tulare Dust,” and “Kern River” to see the truth in it.