Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., who died in February at the age of 89, spent 60 years being famous as an emblem and arbiter of American liberalism, though his importance waned as liberalism’s did. “It’s amazing, in retrospect,” Nicholas Lemann wrote in the Atlantic Monthly in 1998, “what a long string of Presidents—from Truman all the way to Carter—felt a twinge of terror at the possibility of…incurring the disapproval of Arthur Schlesinger.” Schlesinger’s good opinion was tantamount, Lemann notes, to the “good opinion of the centrist-liberal establishment.” His career moved from triumph to triumph during the middle third of the 20th century, when liberalism was ascendant. His second book, The Age of Jackson, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1946, when he was 27. As befits a man who, according to the New York Times obituary, frequently wrote 5,000 words a day, Schlesinger authored more than 20 books and hundreds of articles for periodicals that ranged from Foreign Affairs to Ladies’ Home Journal. Before 1960 he finished three volumes of The Age of Roosevelt—The Crisis of the Old Order (1957), The Coming of the New Deal (1958), and The Politics of Upheaval (1960). (He never completed the remaining volumes, which would have covered the final eight years of Roosevelt’s presidency.)

Schlesinger played a central role in founding Americans for Democratic Action in 1947, and his influential book of 1949, The Vital Center, remains the best expression of the ADA worldview. He was a speechwriter for Adlai Stevenson during the 1952 and 1956 presidential campaigns, but switched to Kennedy in 1960, subsequently accepting Kennedy’s offer to work in the White House as a special assistant. He left the Johnson Administration two months after Dallas, going on to win a second Pulitzer with A Thousand Days (1965), his history of the Kennedy presidency. He was active in Robert Kennedy’s brief presidential campaign in 1968, writing a best-selling biography of RFK ten years later. The last campaign in which Schlesinger played a significant role was Ted Kennedy’s attempt to wrest the Democratic nomination from Jimmy Carter in 1980. Kennedy’s defeat by the more conservative Carter, and then Carter’s defeat by the much more conservative Ronald Reagan, sent Schlesinger—and liberalism—into internal exile. Unlike his seven immediate predecessors in the Oval Office, “Reagan couldn’t have cared less” what Schlesinger had to say, according to Lemann.

Torturing the Facts

After Schlesinger’s death, Sam Tanenhaus, the editor of the New York Times Book Review, lamented the loss of America’s “last great public historian,” who was unique for commanding “broad cultural authority.” More generally, the disappearance of public intellectuals like Schlesinger was decried 20 years ago by Russell Jacoby in The Last Intellectuals (1987): “Younger intellectuals no longer need or want a larger public; they are almost exclusively professors. Campuses are their homes; colleagues their audience; monographs and specialized journals their media…. Their jobs, advancement, and salaries depend on the evaluation of specialists, and this dependence affects the issues broached and the language employed.”

We should be careful what we mourn for. Like two magnets turned the wrong way, the words “public intellectual” (or “popular artist”) resist each other. There’s a tension between engaging with public life in order to influence political outcomes, and following the evidence wherever it leads in pursuit of truth. Any combination of the two requires ruthless candor, with the public and oneself, about when one is speaking as a partisan and when as a truth-seeker. Throughout his long career, Arthur Schlesinger was not, to put it gently, zealous about fulfilling this duty. There was such perfect congruence between Schlesinger’s political preferences and his scholarly conclusions that neither happy coincidence nor honest error can possibly account for it. In the devastating Coolidge and the Historians (1982), Thomas Silver showed that Schlesinger repeatedly and flagrantly tortured the evidence until it confessed. “What the hell,” Schlesinger said in defense of one book. “You have to call them as you see them.” It’s the umpire’s credo—but Schlesinger always wanted to have it both ways, to speak with the authority of an umpire, while competing fiercely as a member of his team.

The Vapid Center

He spent his life promoting liberalism. The fact that, in the end, his brief for it was neither clear nor compelling says more about liberalism’s deficiencies than Schlesinger’s. All of his histories served polemical purposes; it was said that on every page of The Age of Jackson the author voted for Franklin Roosevelt. The Vital Center, however, is Schlesinger’s most important book that presents itself as a polemic. The political center he defended lay somewhere between the reactionary, plutocratic businessmen who had opposed the New Deal, and the Henry Wallace progressives who in 1948 believed that the overriding imperative of American foreign policy must be, in all questions, to give Stalin the benefit of the doubt. The liberalism (or radicalism—The Vital Center used the terms interchangeably) situated on that political real estate had qualities: influenced by Reinhold Niebuhr’s theology, Schlesinger was especially concerned to portray a sober political disposition that was wary about the human capacity for evil, rather than a sentimental creed, optimistic about uplifting human nature through social reform.

What Schlesinger’s liberalism did not have was an essence. The Vital Center goes on about all the things government might do, and all the corresponding difficulties it needs to keep in mind when trying them. What, then, does the revival of American radicalism entail? “The recipe for retaining liberty is not doing everything in one fine logical sweep, but muddling through….” In later years Schlesinger favored the phrase “affirmative government,” which elevated “muddling through” without clarifying it. The only principle “affirmative government” ever clearly affirmed was the need for more government.

E.J. Dionne eulogized Schlesinger in a column, reassuring his readers that “reports of liberalism’s death are always premature,” because the commitment to problem-solving—”the search for remedy,” in Schlesinger’s phrase—is “the antidote to social indifference and to despair about our capacity to act in common through government.” As ideologies go, problem-solving is better than problem-causing. It is, however, a framework that defeats every effort to make distinctions and draw boundaries. There is never any basis in the doctrine of muddling through for saying the government lacks the capacity, wisdom, or legitimate authority to solve a particular problem, or even that some “problems” are really aspects of the human condition that we might ameliorate but cannot eliminate. Incapable of discovering a single dissatisfaction that is not a problem the government might—hence must—solve, the search for remedy easily becomes the search for new afflictions in need of remedy.

The meagerness and uselessness of the “principle” of affirmative government reminds us why the center is rarely vital: there is so little -ism in centrism. In practice, centrism amounts to split-the-difference-ism, which renders muddling through indistinguishable from messing around. The other problem with muddling through as a philosophy of government is that, devoid of any guideposts, benchmarks, or precepts, its practical success is utterly dependent on the quality of the muddlers. The need for capable public officials, however, cannot explain or justify the arrogance that so frequently mars Schlesinger’s writing. Schlesinger did not limit himself to being snide to people who disagreed with him. He had no important policy differences with Harry Truman, for example, but the unprepossessing, accidental president lacked FDR’s pedigree and polish, reason enough for Schlesinger to call Truman “a man of mediocre and limited capacity” who had “managed to surround himself with his intellectual equals.” In print continuously over seven prolific decades, Schlesinger never had an unpublished sneer.

Old Liberalism and the New Politics

According to Fred Siegel, the “political and cultural snobbery that informs The Vital Center” lives on in the hauteur of those “who expect, given their putative expertise, to be obeyed”—and this attitude has proven to be “the undoing of American liberalism.” In view of its intellectual and political preeminence during the middle third of the 20th century, it’s still astounding that liberalism’s undoing took so little doing, that it broke apart in the 1960s and has stayed broken for 40 years. Vietnam, assassinations, and ghetto riots explain only so much of this collapse. The self-assured liberalism that Schlesinger insisted on, the liberalism that shaped the New Frontier and vanquished Barry Goldwater in 1964, turned out to be a flimsy vessel, unseaworthy except in calm waters and mild breezes.

This liberalism was for the people, but not quite of or by them. It preferred them to be objects of an affirmative government directed by their betters rather than agents of an affirmative government able to challenge their betters. It’s one thing to favor a bad policy, as liberals did in the controversy over busing in the 1970s. It’s something else to castigate all opponents of busing as racists, and deny even the possibility that decent, intelligent people might have legitimate misgivings about that dubious policy. This “punitive, ram-it-down-their throats quality,” in Nicholas Lemann’s phrase, belonged to a politics that antagonized people on purpose, because they were deemed to have it coming.

This protean ideology, furthermore, was perfectly suited to repulse the intrusions of mere citizens who didn’t know their place. Muddling-through liberalism might mean lots of things, so there was no way to know if any particular rendering got it right. But the nomenklatura empowered by liberalism had self-interest combined with self-righteousness on their side when heaping abuse on those who got it wrong.

“I remain to this day a New Dealer, unreconstructed and unrepentant,” Schlesinger wrote in his memoirs, A Life in the Twentieth Century, published in 2000. His faith did waver, momentarily, during and after the storms of the 1960s. “With all its faults, the old liberalism had at least arrayed itself against the immovable and impenetrable institutions,” he said in his 1978 biography of Robert Kennedy. “Yet the old liberalism had failed to beat the structures…. In different ways, welfare, public housing, farm price supports, one creation after another of the old liberalism, had congealed into props of the existing order.”

The practitioners of the old liberalism thought America had problems to be solved. They were confident that public-spirited young men, trained by the best colleges and holding their idealism in nice equipoise with their irony, could solve them. The advocates of the “New Politics,” who challenged that liberalism, thought America had sins to be expiated. The enormity of the sins, the suffering of those who had been sinned against, and the spiritually hollow lives of the sins’ beneficiaries, all meant that the smug complacency of the old liberals had to be replaced by frantic moral urgency. Robert Kennedy ultimately sided with the New Politics. Schlesinger records that in 1967 Kennedy told an audience of students, “Don’t you understand that what we are doing to the Vietnamese is not very different than what Hitler did to the Jews?”

Schlesinger’s own rhetoric soon became equally injudicious. In 1968 he gave a commencement address the day after Kennedy was shot, calling Americans “the most frightening people on this planet…because the atrocities we commit trouble so little our official self-righteousness, our invincible conviction of our moral infallibility.” He informed the graduates and their proud parents that Americans could begin to atone for their wickedness only by recognizing “that the evil is in us, that it springs from some dark, intolerable tension in our history and our institutions.”

Schlesinger actively supported George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign. The McGovern Democrats came to a fork in the road between the old liberalism and the New Politics—and took it. That year’s Democratic platform wrapped gauzy rhetoric about authenticity and participatory democracy around expensive promises to every interest group that could fit under the party’s tent. Tom Geoghegan, reporting for the New Republic from Miami’s Democratic convention, observed that the party was caught between two worlds. In one, “politics is expected to deal with the whole man and his sense of helplessness.” In the other, “a faceless bureaucracy indemnifies anyone or any group big enough to make trouble for it.” In short, “Government has failed—give us more government.”

“Neoliberal Nonsense”

Realizing the McGovern Synthesis was untenable—Americans were never going to elect these smug Jeremiahs decrying Americans’ depravity—some of the brightest survivors of McGovernism began to entertain surprisingly skeptical thoughts about the old liberal imperative to give us more government. McGovern’s campaign manager, Gary Hart, was elected to the Senate from Colorado, and promptly declared that the “class of ’74” Democrats were not “a bunch of little Hubert Humphreys.” He later explained that he meant that those Democrats “were not automatic regulators, new-agency creators, and higher-tax-and-spend people.”

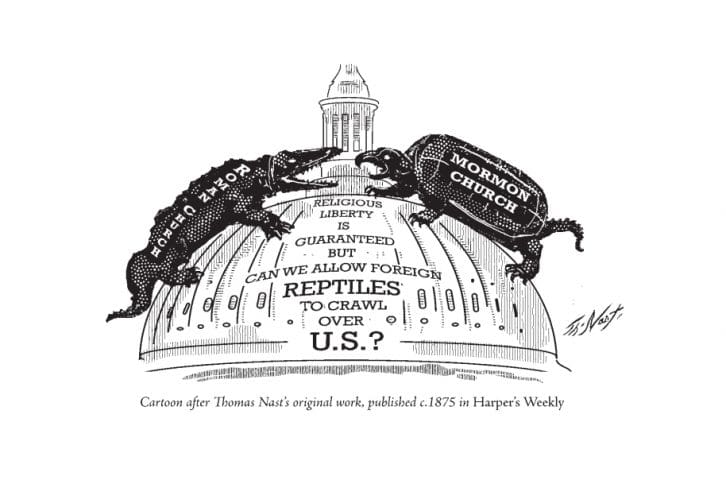

This political impulse eventually acquired a name, neoliberalism, and a magazine, the Washington Monthly. In “A Neoliberal’s Manifesto,” the Monthly‘s editor, Charles Peters, decried the “shortage of self-criticism among liberals.” The neoliberals, he said in his 1983 article, “are against a fat, sloppy, and smug bureaucracy. We want a government that can fire people who can’t or won’t do the job.” He called for means-testing all government transfer programs, including veterans’ benefits and Social Security. Finally, Peters declared, “the snobbery that is most damaging to liberalism is the liberal intellectuals’ contempt for religious, patriotic, and family values.” This contempt is “the least appealing trait of the liberal intellectuals,” many of whom “don’t really believe in democracy.”

On cue, Arthur Schlesinger promptly wrote a book review expressing his contempt—for the neoliberal heretics. He allowed that they had “useful points to make,” but “neoliberalism was a hoax from the start,” one whose “anti-government line” was “a bow to fashion and a bid for publicity.” He called on all liberals to re-embrace the one, true faith in affirmative government, and for “the end of the neoliberal nonsense.”

It’s now clear that the neoliberal nonsense has ended. Neoliberalism failed for two related reasons: first, the imperative to “give us more government” was stronger than any concern about whether government could really solve the problems of those who needed help. Second, this policy imperative meant that self-criticism must yield to the political imperative to fight the real enemy: conservatism.

The upshot, in the words of Mickey Kaus, is the belief that “Democrats shouldn’t spend much time questioning their traditional positions or their institutional allies because that prevents them from being as aggressively and nastily partisan as possible.” While the “Neoliberal Manifesto” lamented liberals’ “unwillingness to acknowledge that there just might be some merit in the other side’s position,” the current editor of the Washington Monthly, Paul Glastris, is more interested in “figuring out how…to fight against [conservatism] than in getting into pissing matches with my friends on the left over whether federal job retraining programs are a false god.” Charlie Peters believed that transfer payments to “my aunt who uses her Social Security check to go to Europe” were unaffordable and indefensible. Glastris is “definitely” opposed to means-testing.

In the crucial respect, neoliberalism and Schlesinger’s vital center failed for the same reason: each tried to remove a “flaw” that proved to be intrinsic to liberalism. The vital center aspired to sobriety about human nature, caution about the possible achievements of social reform, vigilance against freedom’s enemies. In all these ways it proved to be irreconcilable with liberals’ instinctive belief that humans are fundamentally good and fraternal; that war, poverty, and discrimination persist only because of social structures that serve invidious or pathological ends. It was the gravitational pull of this instinct that led Schlesinger the centrist to embrace Robert Kennedy’s view that a war begun “to assure the survival and the success of liberty,” in the words of John Kennedy’s inaugural address, had become morally indistinguishable from the Holocaust.

With every passing year, the vital center grows less vital and less central. Like Arthur Schlesinger’s own career as a public intellectual, it is an artifact of a receding era. He leaves behind a mountain of readable but tendentious books and articles, all of them advocating a liberalism that retains the ability to buy votes but not to change minds.