Books Reviewed

A review of Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem–and What We Should Do About It , by Noah Feldman

, by Noah Feldman

What is the place of religion in American politics? Two extreme opinions battle each other in our culture wars. On one side are secularists who say that because America was the first modern nation without an established church, the founders intended this to be a secular republic. On the other side sit those who point to the centrality of Christianity in the lives of Americans from the founding era to today, and from that fact conclude that America has always been a Christian nation, albeit a non-denominational one.

In his new book, Divided by God: America's Church-State Problem—and What We Should Do About It, Noah Feldman, a professor at New York University's law school, reminds us that this problem has always been with us. Rather than conclude that it is therefore inherent in American politics, he thinks that he has a solution to it. As he sees it, there is nothing wrong with making religious arguments in public, or with public displays of religion—so long as the government does not fund them. He proposes a new bargain in which religious expression would be welcomed back into the public square, but government money would be banned from religious schools and charities (hence no vouchers or faith-based programs).

The trouble with Feldman's solution is that it ignores the history to be found in his book, and it misconstrues the peculiar requirements of our form of government. Although he does not ignore the benefits America has reaped from having a religious citizenry, he spends more time discussing the political abuses of religion and the cut and thrust of America's religious politics. For example, he reminds readers that the First Amendment's guarantee that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof" took shape as a mixture of political principle and calculation. James Madison hoped that it would solidify support for the new U.S. Constitution. Some of the states that approved that amendment had religious establishments they wished to protect from federal interference, and ratified the amendment for that very reason. In 1789, America did not have a religious establishment; it had several religious establishments of various kinds—in addition to some states without establishments. The First Amendment was a political compromise.

Feldman reminds us that when the people ratified the Constitution, and for several generations thereafter, no one thought there was anything wrong with students reading the Bible in school. When public schooling began to spread during Andrew Jackson's presidency, the Bible was a classroom staple. These schools were created not so much to prepare Americans to succeed economically, but to ensure that working-class citizens became educated, responsible voters capable of maintaining the country's republican form of government. As part of this education in liberty, teachers insisted on a new, "nonsectarian" reading of the Bible in order to teach a common morality for citizenship.

* * *

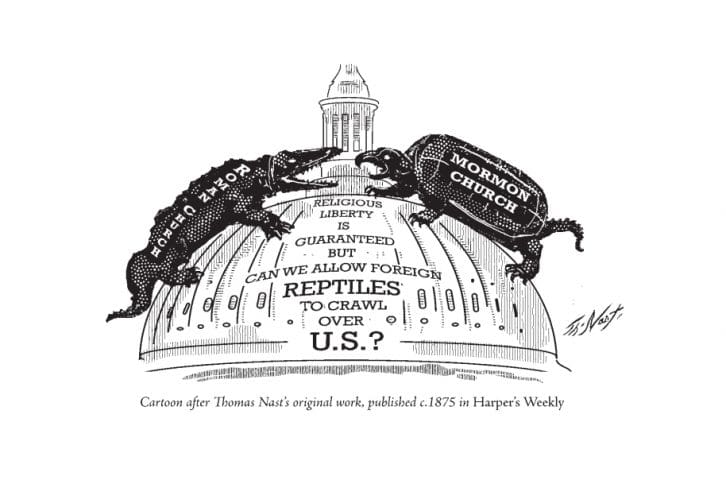

This effort to teach a "nonsectarian" Bible was problematic. Which version was non-sectarian? For Catholics, the Bible—and especially the King James Bible—was insufficient to convey a complete picture of what God asks of men. Feldman notes that when John Locke began to propose religious toleration in the 17th century, he excluded Roman Catholics, Muslims, and atheists from its protections—the last because they had no transcendent reason to be good, even if they were good; and the first two because they were potentially subjects of a foreign potentate, whether the Pope or the Caliph. (The U.S. acted similarly by outlawing certain forms of Shinto during World War II, because the Shintoists were worshiping the head of state of a country with which the United States was at war.)

As Catholics began to arrive in vast numbers to America's shores in the mid-19th century, their influx created a strain within the public schools. Learning from both Locke and their own Protestant forebears that Catholics could not be good citizens so long as they were "Papists," the schoolmasters sought to Americanize the new immigrants. The result was predictable. Catholic Americans (and, Feldman could have added, Lutherans and the Dutch Reformed and German Reformed) began to organize their own schools, to educate their children in the context of their own religious doctrines. They also began to argue that if the state had an interest in the education of children, shouldn't it support these new schools as well? And if the state did not, weren't Catholics being unfairly taxed for schools they didn't use?

Meanwhile, evangelicals, liberal Protestants, and Unitarians joined with nativists to insist that government should not support any schools but its own. Tensions led to violent riots in Philadelphia in 1844. As Feldman points out:

The Bible wars of the mid-nineteenth century did not reflect any particularly deep religious faith on the part of the nativists who took to the streets. The Bible mattered as a symbol of American Protestantism and the republican ideology connected with it…. Loss of control over what was taught in the schools would be evidence of lost control over the public meaning of American life.

In short, America's Protestant majority drew a straight line between the basic Protestant idea that all Christians ought to read and reflect upon the Bible for themselves and American citizenship. Catholicism, as they understood it, taught that Christians should listen passively to the educated priestly class and the Church hierarchy. Catholics, for their part, protested that public education was a stalking horse for Protestantizing their children, and sought other means of education. Both sides saw that education was at once a religious and a political thing.

* * *

This feud between Protestants and Catholics is the context in which to understand secularism—defining morals without regard to God—which began to gain influence after the publication of Charles Darwin's Origin of Species in 1859. "The relegation of religion to the realm of personal spirituality, accompanied by a rejection of the Bible as a source of objective knowledge about the world," writes Feldman, constituted the "core" of late 19th-century American secularism. To gain a hearing for their unpopular views, secularists shrewdly "used the Catholic church, which had for so long dominated European Christianity, as a stand-in for religious belief more generally." In this way, "[b]y making the Catholic church the main antagonist of science, the secularists defined an enemy that their Protestant audience already loved to hate." To gain ground in American politics, secularists sided with Protestants against Catholics; all the while they set precedents that they would later use against Protestantism itself. (Similarly, in the 20th century, Mexico drafted anticlerical laws against Catholics and then used them to restrict Protestants, and Turkey drafted laws to control Muslims that they then used to stifle Christians.) By the 20th century, many evangelicals began to think about church-state relations, and about science, in these secular terms. A related movement that Feldman calls "legal secularism" was developed not by secularists, but by a cultic faith known as the Jehovah's Witnesses, who thought that the new custom of saluting the American flag in schools was idolatrous.

Feldman doesn't give enough credit to the role of the Masonic movement in this process. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Masons taught American middle-class men that, regardless of what the church said, there were many paths to God, and inculcated in them a highly relativized, hyper-nonsectarian spirituality—but not a relativized morality until the 1960s—that was secular in fact, though not secularist.

* * *

The basic problem remained: what, other than religion, could provide a common moral foundation for American citizens? And if "religion" was indispensable, which one or ones? After World War II, the answer was found in the idea of a generic biblical religion. Once the horror of the Holocaust came to light, Americans recoiled from its godless depravity. Facing a new atheistic enemy in the Cold War, the phrase "under God" was added to the Pledge of Allegiance at the behest of the Knights of Columbus and "In God We Trust" became the national motto. But what God? A new term, "Judeo-Christian," was coined, going beyond the old non-sectarianism. It grew from the not implausible argument that the biblical religions inhabited a common moral universe. Protestants, Catholics, and Jews shared the same basic beliefs about human nature, sexual morality, and honesty and decency. It was precisely this moral consensus that came under attack in the 1960s, and remains under attack in today's culture wars.

Feldman seems puzzled by this outcome. Although "liberals have mostly been winning the culture war…conservatives have been winning the war over institutions and…social policies." The upshot, he says, is "a contradiction, or rather a series of contradictions." He writes:

Victories by the legal secularists have removed religion from formal public spaces such as schools, at least during school hours. Successful efforts by values evangelicals have broken down once-strong institutional barriers between the state and organized religion, and have actually increased the degree of religious discourse in politics.

* * *

The American people remain a religious people. And yet America's elite—at least its academic elite and those who listen to them—are evangelists for secularism. The secular elites control our law schools, and hence our courts. But the religious usually decide our elections. That analysis leads to Feldman's proposed solution: let religious people say all they want in public, even in political discussions, but let the rules stand that secular liberals have pushed through the courts.

From the point of view of America's conservatives, Feldman's solution is no solution at all. A prescription more sensitive to the history the author so ably outlines would begin by insisting on a distinction between the duties we owe to God and those that we owe to each other, represented by the first and second tables of the Ten Commandments, respectively. Our duty to God is none of the government's business. Our duties to each other are the foundation of our legal system. Admittedly, the problem of education is a little more complex. Education, it can be argued, has a quasi-religious function because it is about the world, which is God's world, and about character formation, which touches church and family as well as state. In the West, only the United States and France insist that publicly funded education must come exclusively from state-run schools. Secularists may be down on our health-care and death-penalty policies, but here is one instance of American exceptionalism that they actually defend! On the basis of Feldman's own evidence, however, it is no infringement of our freedoms if universal education, operating at the local level, were to include home schooling and parochial instruction as well as the public schools.