Books Reviewed

Sandy Levinson is an iconoclastic law professor. Though unabashedly on the left, he fairly delights in taking stances that challenge his fellow academic liberals. He is famous among gun-rights advocates for his 1989 Yale Law Journal article, “The Embarrassing Second Amendment.” Before that article it was considered disreputable among constitutional scholars even to suggest that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to own guns. By legitimating an individual rights interpretation, Levinson’s article inspired a wave of complementary scholarship in the 1990s that even persuaded Harvard law professor Laurence Tribe to reverse his treatment of the Second Amendment in his widely read treatise on constitutional law. The cumulative effect of the scholarship that followed in Levinson’s wake eventually led to the recent decisions by federal courts of appeals in the Fifth and D.C. circuits to adopt an individual rights interpretation of the Second Amendment.

Around the same time, another article by Levinson in a symposium on the Ninth Amendment helped revive academic interest in the original meaning of that “forgotten” passage of the Constitution. To play a key role in reviving two out of the ten amendments in the Bill of Rights is no small achievement. Nor was it accidental. Levinson has a deep commitment to a consistent interpretation of the whole text of the Constitution, refusing to cherry-pick the portions of the text he likes while discarding the rest.

He is well known among legal scholars for his rejection of what he calls the “happy endings” approach to constitutional interpretation, by which clever analysis gets the interpreter whatever result he wants. Levinson insists that any method that always leads to the results you like is not truly interpretation. Unless a method of interpretation produces some results with which its proponents are seriously unhappy, it is doing nothing more than reading their preferences into the Constitution. His insight has reshaped the entire field of constitutional law.

To be sure, he is no originalist. He does not believe that the meaning of the Constitution must remain the same until it is changed by a properly ratified written amendment. But he does insist that any method of interpretation must take the entire text seriously. For Levinson, who was a strong proponent of gun control at the time he published his Yale piece, the individual right to keep and bear arms was an “unhappy ending.” But it was a price he was willing to pay for a consistent approach to constitutional interpretation that would yield happier endings from other portions of the text, including those that the Right might prefer to ignore: such as the Ninth Amendment’s protection of unenumerated rights.

This deep intellectual integrity is also manifested in Levinson’s pioneering casebook in constitutional law, which he co-authored with Paul Brest, the former dean of Stanford Law School. Instead of being organized by doctrine or subject like other casebooks, Levinson’s is richly historical and chronological. Whereas casebooks typically begin with Marbury v. Madison (1803), Levinson’s begins with the 1791 debate in Congress and the executive branch over the first great constitutional controversy—the establishment of a national bank. Not only does this emphasize the importance of the Constitution’s original meaning, it displaces the courts in general and the Marshall Court in particular from their customary centrality in constitutional law.

A century ago the Progressives seized upon certain parts of John Marshall’s opinions as a way to justify their own expansive views of federal power; and all other casebooks have comfortably accepted this framework. Not Levinson. His book confronts students with the views of Madison, Jefferson, Randolph, and Hamilton before they ever hear from Marshall. Levinson’s interest in “the Constitution outside the courts” preceded by many years, and influenced greatly, the similar emphasis by Mark Tushnet, Larry Kramer, and Cass Sunstein.

In these ways, few have done as much to advance originalism as this non-originalist man of the Left. From his principled commitment to textual consistency, it is a short step to the view that “the meaning of the Constitution must remain the same until it is properly changed,” which is another way of defining a proper originalism. Indeed, his frequent co-author, Yale law professor Jack Balkin, recently stepped across the line to endorse originalism, much to Levinson’s chagrin.

* * *

His new book, our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes Wrong (And How We the People Can Correct It), represents an important shift in Levinson’s thinking, though not in his interpretive method. While he once thought that, on the whole, the happy endings of a consistent reading of the Constitution outweighed the unhappy ones, he is now convinced that the Constitution “is radically defective in a number of important ways.” In particular, he has become “ever more despondent about many structural provisions of the Constitution that place almost insurmountable barriers in the way of any acceptable notion of democracy.” Still not one to evade the text’s meaning, this book is Levinson’s manifesto for a new constitutional convention to fix these many constitutional defects.

Our Undemocratic Constitution is two books in one. First, it provides a useful critique of several flaws in constitutionally established procedures, defects which are at least mildly disturbing. For example, he notes how difficult it would be to reconstitute Congress in the wake of a deadly terrorist attack against its members. He bemoans as well the mischief a lame-duck Congress of one party can do before its successors are sworn in, and the lengthy delay before a newly elected president takes office.

Second, the book is an impassioned critique of the “undemocratic” aspects of the Constitution. Levinson is no fan of the electoral college, or of the various choke points in the legislative process, especially the presidential veto. Nor does he care much for the pardon power. He opposes life tenure for unelected federal judges, and is positively indignant about the equal representation in the Senate that the Constitution affords every state regardless of population. He also strongly objects to the fact that incompetent and unpopular presidents get to serve out their terms, rather than being replaced (as in parliamentary systems) by their own party when the leader’s fecklessness becomes apparent and public opinion turns.

His entire critique is a tribute to his textualism: he does not believe these alleged defects can be wished away by creative interpretation. But he refuses to suggest remedies, insisting that he is merely rallying a constituency for a constitutional convention where these matters will be decided, rather than pushing any particular solution to the problems he identifies. True, to make the case against the Constitution’s defects, Levinson identifies alternatives from other countries, and he seems particularly fond of parliamentary systems, which have beguiled the American Left at least since Woodrow Wilson. But by failing to prescribe specific remedies for the ills he identifies, Levinson is unlikely to overcome the current resistance to constitutional reform.

The book would have been far more effective if it had included a proposal for an omnibus constitutional amendment addressing all these flaws. But because another one of Levinson’s bugbears is the Article V amendment process itself—requiring a supermajoritarian approval by states with unequal populations—even suggesting a constitutional amendment runs against his grain. That’s particularly unfortunate since he has no real objection to a written constitution. Simply putting his proposed fixes in written form would not have committed him to the arduous and “undemocratic” ratification process of Article V. But it would have forced him to be clear about what he is for and not just what he is against.

But Our Undemocratic Constitution has deeper problems. For a start, the book’s indictment of flaws in the Constitution is at odds with its critique of “our undemocratic Constitution.” Why aren’t these defects being addressed by the democratic components of the current political process? After all, Levinson doesn’t claim that reforms are being blocked by the “undemocratic” features of the Constitution; it seems rather that these issues just aren’t attractive enough to ignite populist passions. To put it differently, there is no political incentive for democratically elected officials to look down the road and address these potentially awful results of very low probability events.

This is a well-known problem with government itself, especially of more “democratic” governments. Because government officials own no stock in “the company,” so to speak, the long term is not nearly as important to them as the next election. And solving the problem of how Members of Congress will be selected after a nuclear strike on D.C. is not going to make any difference in the next election—especially because in the long run they’ll all be dead. Contrary to primitive critiques of capitalism, private firms are far more future-oriented than government. It’s a fair guess that the more democratic we make the Constitution, the less likely it is that these problems will be addressed.

An “undemocratic constitution” could mean one of two things. The first is something like a monarchy or dictatorship. The second is that there are too many veto points in our system by which political minorities can block majoritarian rule. When criticizing “our undemocratic constitution,” Levinson clearly means the second. Indeed, a more accurate title for his book would be, “Our Counter-Majoritarian Constitution.” But that wouldn’t have the same appeal, because most Americans are not majoritarians—or more accurately, most Americans are not pure majoritarians. Neither, for that matter, is Sandy Levinson.

* * *

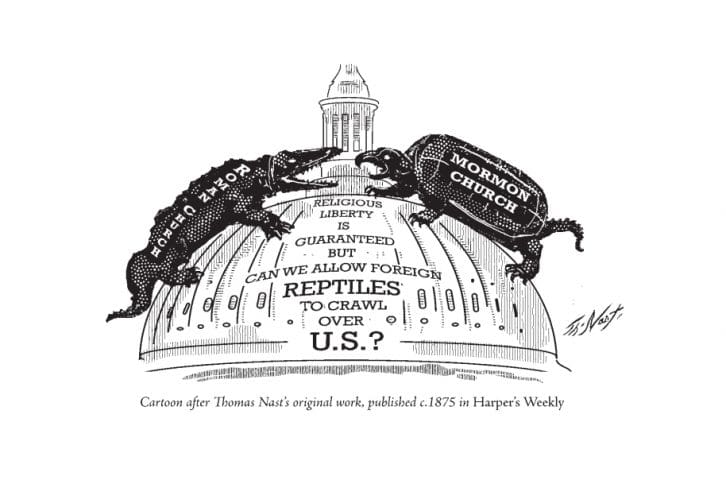

To the founders, “republicanism” required the people to have ultimate control of the government while “democracy” meant naked rule by the majority. The authors of the Constitution had developed grave doubts about the majoritarian rule they saw in abusive state legislatures and in the feckless one-house Congress established by the Articles of Confederation. Their goal was to cabin the ill-effects of majoritarianism. Here is how Madison explained this to Congress when introducing the Bill of Rights: “The prescriptions in favor of liberty, ought to be levelled against that quarter where the greatest danger lies, namely, that which possesses the highest prerogative of power: but this [is] not found in either the executive or legislative departments of government, but in the body of the people, operating by the majority against the minority.”

In the founders’ republican form of government, the people retain their sovereignty through numerous checks on government power but do not themselves rule day to day. The founders’ concern was somehow to empower an “energetic” government to advance the general welfare while preventing it from violating the rights of the majority or a minority, or even the rights of a single individual. So if democracy equals simple majority rule, as it did for the founders, then the Constitution is not only undemocratic, it is downright anti-democratic.

But the Constitution reshaped the American concept of democracy so as to distinguish it from pure majority rule. In today’s understanding, democracy allows a place for majority rule, but only as filtered through a complex system of federalism, separation of powers, and expressed protections of rights. As a result, it cannot be said that the Constitution is undemocratic simply because it has substantial counter-majoritarian features. Majority rule checked by counter-majoritarian procedures defines the modern conception of democracy itself.

Levinson’s rhetoric about our undemocratic Constitution amounts, then, to an appeal to alter the Constitution’s current ratio of majoritarian to counter-majoritarian elements in favor of increased majoritarianism. Yet he never clearly explains exactly how and why we would be better off with more majoritarianism than we now have. Perhaps under his system it would be easier to enact National Health Care. Or perhaps, instead, it would be easier to enact Private Retirement Accounts. To convince others to embrace a more majoritarian constitution, however, Levinson needs to show why the desire to achieve one’s own policy objectives should overrule the fear that one’s opponents might achieve theirs. He sees the problem:

Is it worth it, in order to deprive your opponents of the opportunity to work their political will, to make it more difficult to pass your own favorite programs? Or, on the contrary, would you rather have a greater likelihood of achieving your own goals even if this means that your opponents would be more likely to succeed if and when they are in power?

Because most Americans do not consider enacting government programs to be among their “own goals,” most answer these questions differently than Levinson. Even policy wonks often fear their opponents’ “political will” far more than they desire their “own favorite programs.”

* * *

Which returns us to our counter-majoritarian Constitution. It is counter-majoritarian by design. Precisely because the founders feared majoritarian fecklessness and abuse, they inserted the veto points to which Levinson objects. Most people today—whether left, right, or libertarian—still fear majoritarian rule. They believe they have more to fear from their political opponents gaining power than they have to gain from putting their friends in office. Indeed, many Americans revere the Constitution precisely because of its counter-majoritarianism—the checks and balances adopted by the founders.

It has become de rigueur among American constitutional law scholars to refrain from recommending our particular form of government to others when advocating democracy around the world. While most Americans prefer the safety of our counter-majoritarian Constitution, our constitutional “experts” are happy to urge others to live the truly majoritarian ideal. Now Sandy Levinson is urging Americans as well to adopt a more majoritarian constitution. But maybe the time has come instead to let the rest of the world in on our little secret.