Books Reviewed

A review of The Book of Man: Readings on the Path to Manhood , by William J. Bennett

, by William J. Bennett

Compared to their female classmates in schools and colleges, today's boys and young men are getting, to use an old sports idiom, smoked. Boys are diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) at a more than two-to-one ratio over girls. Boys trail girls in high-school graduation by at least 7%. Women attend and graduate from college in higher numbers than men. In 2004 women earned 58% of bachelors' degrees. Increasingly colleges are lowering admissions standards for men, the new minority, even to maintain what is becoming the 60/40 norm. What is less well known to those outside the academy is what men do—or fail to do—on campus. On average, men's grades are a half to a full point below women's. This disparity isn't the result of men being so busy dominating, a là Ronald Reagan at Eureka College, in sports, theatre, and student government. Men may still have an edge in sports, but women increasingly control the positions of leadership and influence on campus. In addition, women volunteer off campus—in churches, soup kitchens, political campaigns—at astonishing rates. I suspect that women also work more often than men to put themselves through college; at the very least, they do not work less.

If women are busy studying, leading, volunteering, and working, what are the men doing? Drinking and playing video games, apparently. According to recent studies, half of college males spend on average over two hours a day gaming. They binge drink. And despite their passion for video games, they haven't abandoned TV, watching anything from reruns of Cops to log rolling on ESPN. Were men to snap out of it after school or college, being outdistanced by women in their studies would be no more than a professor's concern. Yet every indication is that men do not snap out of it.

At least one day a week, prompted by sorority customs, young women on many college campuses do something highly irregular in the Age of Denim. They dress up. They become more than attractive. They look mature. They look like they will soon have interesting jobs, that they are ready to be wives and, sooner than you think, mothers. In short, they look like they know what they're doing, not just as students or human beings but as women. The young men in the class—wearing those long, goofy basketball shorts with a lanyard hanging out of one pocket—look like, well, schlubs. It's not altogether clear that these boy-men will soon be doing anything interesting or important, including becoming husbands and fathers.

* * *

The failure of today's young males to grow up and become men owes to many factors: economic change, the breakdown of the home, and cultural hostility towards traditional manhood, among other things. Yet their educators bear part of the blame. Today's schools and colleges treat boys as androgynous humanoids rather than as men in the making. Male students, for example, are hardly lining up to take philosophy classes. And why should they? Ethics professors themselves usually don't realize that Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics and Cicero's On Duties, once the staples of a college education, are books designed in part to teach men how to live. Military history has all but vanished since, as we moderns have decided, war is not the answer. Heroes are out of fashion: the old ones were racists and oppressors. Accordingly, the world of education has nothing to say to the male sex, nothing that speaks to boys' latent spirited nature.

Perhaps no American understands the crisis better than former Secretary of Education William J. Bennett. And he has a remedy: to give boys and young men the education they deserve, an education in manhood. The Book of Man, a comprehensive and engaging selection of readings, is a worthy beginning to that education. The book is organized into six sections: man in war; man at work; man in play, sports, and leisure; man in the polis; man with woman and children; and man in prayer and reflection. This order is fitting, because war is the place to begin the discussion about modern manhood. Man's signature virtue has always been courage, and without the courage to defend family and civil society, those institutions cannot exist with any security.

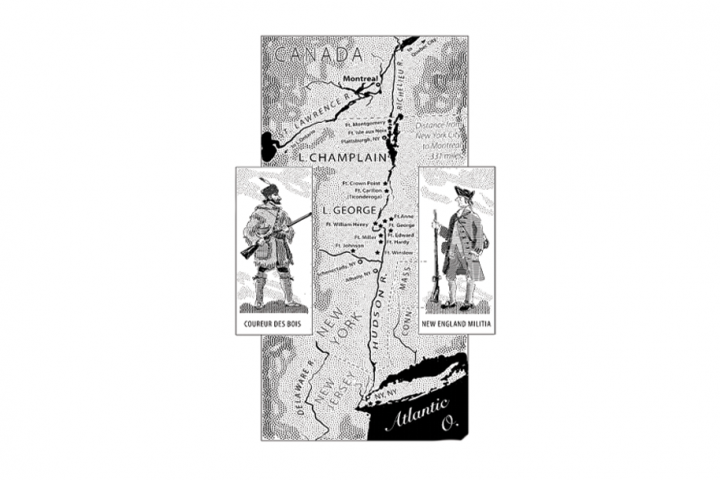

Bennett's illustrations of man fighting are not of warmongers but of men who accept war as a solemn duty in a world full of danger. In addition to essential selections from Pericles, the Bible (David and Goliath), Henry V, and Winston Churchill, Bennett offers portraits of Sergeant York, Audie Murphy, and the Marines, SEALs, and soldiers of today. One piece features the heroism of Rick Rescorla, a Briton who was a child during World War II, served in the British Army, moved to America and served in Vietnam with distinction, and later worked as head of security for Morgan Stanley in the Twin Towers. Not only did he caution officials about the possibility of a truck bomb a year before the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, he warned of the possibility of a plane attack—and for years required Morgan Stanley employees to conduct evacuation drills. On September 11 all but six of the company's 2,700 World Trade Center employees got out of the building; Rescorla was among those killed. His last known words came to his wife over a cell phone: "Stop crying. I have to get my people out…. I want you to know that you made my life."

* * *

Men do more than fight; they work. The chapter "Man at Work" offers well-chosen selections from Benjamin Franklin, Jack London, Booker T. Washington, and Alexis de Toqueville, all testifying to the value and the ultimate purposes of work. The American work ethic is illustrated by famous men like George Gershwin and admirable men like Terry Toussaint, who describes himself as a "proud sanitation worker." He is the supervisor of the Fort Valley, Georgia, Sanitation Department. What Toussaint calls his "sense of pride in keeping the flow going, keeping the trash moving" serves as a telling corrective to the mock outrage on the Left over Newt Gingrich's supposedly insensitive suggestion that children in schools could acquire a work ethic while helping out as janitors. Making the world cleaner, keeping the dust out of our eyes, as Ben Franklin attested, is nothing to sneeze at.

The chapter on leisure is dedicated principally to sports, an area in which boys and men should need no instruction. Yet the readings in The Book of Man promise to raise men out of the mere techniques and tactics of sports in order to understand the great games: baseball, football, basketball, even mountain climbing. Fans of LeBron James and Kobe Bryant will be surprised to learn that practically every magical move on the basketball court (other than the dunk) was pioneered by skinny "Pistol" Pete Maravich, still the all-time highest scorer in the NCAA. Maravich's secret, other than being the son of a basketball coach, was creating his own workout regime that included dribbling from a moving vehicle while his father drove the car. Bill Bennett shows that sport brings out the perfection that can only be the result of spirited competition. He includes a striking 1976 essay of his own on this theme, written at a time when sports was first coming under attack by what he calls dime-store Marxists. "Sports is still an activity in which excellence can be seen and reached for and approximated each day; sports has been relatively unaffected by the general erosion of standards in the culture at large," he writes.

* * *

Man is a political animal, and so Bennett includes several short selections from Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, and Tocqueville. To this sketch of political philosophy he adds the history of men acting as citizens: Cincinnatus, Cato the Younger, George Washington, and a host of striking modern examples. He tells the story of an American Muslim who served as a medical doctor in the Navy and later as a physician to the U.S. Congress. This gentleman, Dr. Zuhdi Jasser, has taken heat from the Muslim community for being outspoken against the attacks of September 11 and for claiming that the modern jihad is a complete misreading of the Koran. Jasser attempts to cultivate what he calls "Jeffersonian Muslims," and, like Jefferson, holds that people of different religions should be able to live together in civil society. Similar themes of citizenship are explored though portraits of men in law enforcement, the famous inner-city math teacher Jaime Escalante, and Álvaro Uribe Vélez of Colombia. To articulate the beauty of civic action, the chapter includes the stirring words of preachers and statesmen. Lincoln's Lyceum Address is there, along with parts of speeches from Daniel Webster, Calvin Coolidge, and John F. Kennedy. In his Farewell Address, President Reagan tells the story of a small boat of Asian refugees rescued by American sailors. When one of the escapees of Communist tyranny saw the Americans, he yelled, "Hello, American sailor. Hello, freedom man." Young men will learn from such true stories that freedom is a civic good men cannot have without fighting, in peace and in war.

The Book of Man's chapter on women and children, urging a return to the ideal of the gentleman, is both moving and instructive—and a needed corrective for a generation of men who haven't risen to the challenge of fatherhood. The classics are present, among them Hector's beautiful prayer for his son (though, strangely, not rendered in verse), Adam's poetic encomium on first seeing Eve, and Edgar Allan Poe's "Annabel Lee." Just as heartrending is Calvin Coolidge's account of his son's death at 16. The message these stories and poems communicate is essential for today's young man. In a 19th-century American preacher's words, contained in the volume, "Lust will degrade you; love will elevate you…. Lust will make you earthly, sensual, devilish; love will make you godlike, continent, noble."

* * *

Fittingly, The Book of Man ends in prayer. The prayers of the church and of men throughout the ages show how to honor and serve and ask the blessings of God. The model of the courageous martyr in this section acts, though less visibly, as the counterpart to the courageous man of arms in the first chapter, completing the trinity of family, country, God—the cherished ends of man's noble service. Illustrating the pursuits and principles of men throughout the ages, The Book of Man is put together in the spirit of Reagan's First Inaugural, showing that those who say there are no heroes any longer just don't know where to look.