Books Reviewed

A review of Conquered into Liberty: Two Centuries of Battles along the Great Warpath that Made the American Way of War , by Eliot A. Cohen

, by Eliot A. Cohen

Shortly after the United States responded to 9/11 by striking al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan, Javier Solana, the European Union high representative for foreign policy, offered an explanation of the American actions based upon his perception of the differences between Europe and the United States:

Europe has been the territory of war, and we have worked to prevent wars through building relations with other countries. The US has never been the territory of war—that's why September 11 was so important: it was the first time their territory had been attacked.

Mr. Solana had apparently never heard of Pearl Harbor, nor of the American Civil War. And if he didn't know about those conflicts, he couldn't possibly have had any inkling about the "Great Warpath."

In his exceptional book Conquered into Liberty, Eliot Cohen rightly calls Solana's remarks an example of "breathtaking ignorance" that contributes "to a profound misunderstanding of how the United States uses armed force." The reality is, as Cohen shows, that since colonial times, the United States has indeed been "the territory of war."

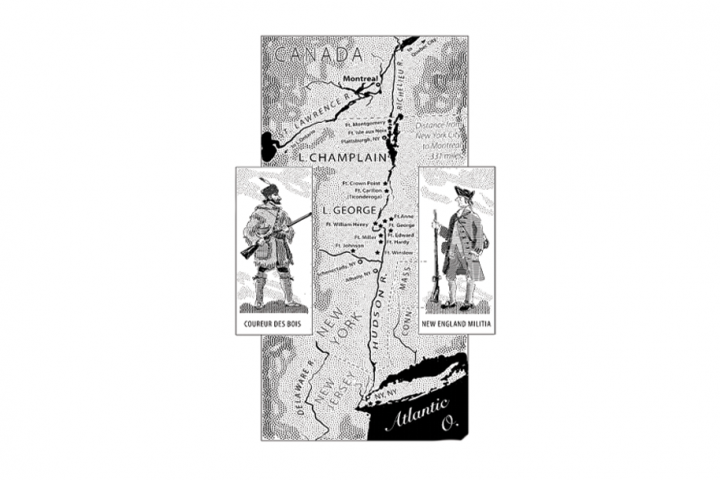

With this volume, Cohen, a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), achieves a scholar's dream: to write a serious book about a boyhood passion, in this case the battles and campaigns that took place over two centuries along the "great water route between New York City and Montreal, along the Hudson and most particularly along Lakes George and Champlain." Unfortunately, unless they have read historians like Francis Parkman or novelists like James Fenimore Cooper and Kenneth Roberts, most Americans, too, are ignorant of the Great Warpath.

Cohen validates John Keegan's claim that geography is the Rosetta Stone of battles. The geography of the Great Warpath helped to shape the strategy of the long struggle between the French and British in North America, between both European powers and the Indian nations of the region, between the British and the United States during the American Revolution and the War of 1812, and finally between the United States and Canada until nearly the end of the 19th century.

Cohen returns this corridor to its position of central importance in the military and political history of the United States. Long before the two great conflicts of the 20th century, world wars reverberated in North America along this great path: the Nine Years' War (called by the French the War of the League of Augsburg and by the English colonists of North America King William's War, 1688-1697), the Wars of the Spanish and the Austrian Succession (1701-1714 and 1740-1748 respectively), the Seven Years' War (called by the English colonists the French and Indian War, 1756-1763), the American Revolution, and the Wars of the French Revolution and Empire. As Cohen observes, "what is now the United States has never really been isolated from global geopolitics, and never can be."

* * *

The French, British, and the Indian nations of North America often fought among themselves independently of the wars in Europe, but always for strategic and political goals. One of Cohen's most important contributions is to counter the popular Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee-view of the North American Indians as victims. He shows that the Indian nations boldly pursued their strategic interests when they allied with one or the other European power. For instance, the Iroquois, comprising the formidable Five Nations (later the Six when the Tuscarora joined the original Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk) allied with the British against both the French and later the Americans. Cohen's welcome revisionism complements that found in two recent studies of the Comanche, The Comanche Empire by Pekka Hamalainen (2008) and Empire of the Summer Moon by S.C. Gwynne (2010), which portray the Comanche as central geopolitical players on the American Great Plains, much as the Iroqois were along the Great Warpath.

The Iroquois strategic goals were forthright: to establish regional hegemony, to control the fur trade, and to win glory, motives not unlike those described by Thucydides: fear, honor, interest. Accordingly, the Iroquois "harassed and slashed at the French colony in Canada, which attempted, by turns, to appease, divide, and when unavoidable, confront them."

The French and the Hurons allied with each other for the same reason the Iroquois and the British did. Each European power understood it could never gain access to the furs of the West or to the (mythical) passage to the Asian sea without native allies. "The upshot," Cohen observes, "was a series of brutal wars…which lasted through much of the middle of the 17th century."

* * *

A central claim of Conquered into Liberty is that two centuries of warfare along the Great Warpath forged the "American way of war." Thanks to the late Russell Weigley, the historian who coined the phrase, the American way of war conjures up the vision of a reliance on the mobilization of vast material resources to grind down an adversary with firepower and mass. Max Boot has suggested that there is an alternative American way of war centered around "small wars" undertaken not to protect or advance vital national interests, but for lesser reasons like inflicting punishment on such peripheral adversaries as Indian tribes and Philippine insurrectos, protecting property and commercial interests, and pacifying native peoples. As many critics have observed, both Weigley and Boot are describing a way of battle rather than a way of war.

Regardless, Cohen argues that the American experience on the Great Warpath greatly influenced American strategic and military culture in a way that is not often appreciated by the followers of Weigley. Cohen's assessment is much closer to Boot's: the Great Warpath taught Americans to recognize the difficulty that conventional armies face in coping with irregular opponents; understand the relationship between the professional soldier, the citizen soldier, and the democratic politician; focus on small unit excellence and cross-border raiding, what we call "special operations" (one of the U.S. Army's Ranger Regiments claims lineage from Roger's Rangers); and adapt rapidly to contingencies. The British found this out the hard way.

As the author observes, "the summer 1758 campaign along the Great Warpath…helped train a generation of American officers who could build and lead armies to fight for American independence." While British generals disdained the "provincials" who comprised the bulk of American troops fighting the French during the French and Indian War, the Americans had learned much during the conflict: "the basics of how to raise, equip, and discipline battalions,…light infantry and ranging tactics…how to organize, move, and sustain substantial force, even in the wilderness."

Cohen focuses not on "decisive" battles (since few battles are ever truly decisive) but on what he calls "revealing battles—contests that illuminated both the larger conflict and some enduring features of an American way of war that it engendered." Many are little known—for example, the French and Indian raid on Schenectady in 1690, which reflected the French strategy of terrorizing the English population and tying down local forces; the French and Indian siege of Fort William Henry in 1757, the dramatic setting for James Fennimore Cooper's Last of the Mohicans and the excellent 1992 movie starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Madeleine Stowe; Fort Carillon, a French victory that (because of its effect on the thinking of Montcalm) contributed to the French defeat on the Plains of Abraham, the fall of Quebec, and the final destruction of New France in Canada.

Cohen also examines the St. Johns campaign of 1775 and Plattsburg in 1814. The first was a precursor to the near capture of Quebec by the Americans at the outset of the Revolution and marked the emergence of one of the most remarkable characters of the American War of Independence, Benedict Arnold. The second effectively ended the War of 1812 by preventing a British invasion of the United States that could well have resulted in a peace foreclosing American expansion to the West.

* * *

In addition to his revisionist treatment of the North American Indians as sophisticated players in the game of geopolitics, Cohen makes a number of other interesting observations. For instance, when Americans equate treason and Benedict Arnold, they avoid some troubling and painful reflections about the American past. Although Arnold's treason rattled the leadership of the American Revolution, he ultimately had no impact on the outcome of the war itself. By contrast, Confederate leaders such as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson came close to destroying the Union created by the American Revolution. "When Arnold, a mere civilian, took up arms, he had no country to which he had sworn allegiance: the soldiers of the United States Army who doffed blue for gray uniforms most definitely had."

Another case of potential treason during the American Revolution involved Vermont, which had declared its own independence from New York in 1777 and petitioned Congress for recognition. Of course, New York violently opposed Vermont, but so did Virginia and many Southern states. Part of the opposition was sectional—Vermont's constitution had banned slavery—but a separate concern was that Vermont would set a precedent for limiting the extensive territorial claims of other states and for dismemberment of states through secession. The British sought to exploit the situation by essentially offering Vermont a royal charter and providing British troops for the colony's defense. Vermonters such as Ethan Allen and the governor were in negotiations with the British until Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown made it clear that the tide of war had turned.

* * *

Cohen's last chapter makes the long-forgotten point that despite such diplomatic achievements as the Rush-Bagot Treaty banning a naval buildup on the Great Lakes, the United States and Great Britain nearly went to war on several subsequent occasions, including the Trent Affair and the Confederate use of Canadian territory to launch a raid on St. Albans, Vermont during the Civil War, and the "Fenian" episode in 1866. "When the last serious war along [the Great Warpath] ended in 1815, few believed that it was indeed such."

Conquered into Liberty is a riveting book that not only refreshes our memory about a critical part of American history but also uses that history to provide a context for how to think about the present. Its title comes from a subversive pamphlet that American revolutionaries distributed in advance of their 1775 invasion of Canada combining promise and menace: "you have been conquered into liberty, if you act as you ought." Thus the campaign against Canada reflected a distinctively American combination of idealism and calculating Realpolitik. "In years to come, Americans in many other places—from Mexico to the Philippines, Vietnam to Iraq—would behave similarly," notes Cohen, "waging wars for liberty and interest, conquering others into freedom, and as in Canada, with mixed motives and uncertain outcomes."