High-brow scuttlebutt is rich with famous last words. “Enough”: Kant. “More light”: Goethe. “Thomas Jefferson still lives”: John Adams. “I think I am becoming a god”: the Emperor Vespasian. The roll of famous first words is scanty by comparison; the infant’s first gurgling “Mama” does not leave a lasting mark in the annals of culture. But then there is Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859), who observed watchful silence until the age of four, and then replied to a lady who clucked and fussed over him when he was scalded by spilled coffee, “Thank you, madam, the agony has abated somewhat.”

Without lapsing into tomfoolery, one can see here in embryo the sterling parliamentary orator, the formidable imperial administrator, the magniloquent essayist and poet and historian. The style already runs to the solemn, the officious, the florid: the startling elevated diction that is a hoot coming from a small boy develops into the stock-in-trade of the celebrated speaker and composer of mandarin prose. At four Macaulay was talking like a book, and at seven he was writing the first book of his own, the Compendium of Universal History from the Creation to Modern Times. Preparation was underway for the essays on Machiavelli, Frederick the Great, Lord Clive, Warren Hastings, Lord Byron, and numerous others; the ballads celebrating the great republican warriors, Lays of Ancient Rome; and The History of England from the Accession of James II, published in five volumes from 1848 to 1861, which would be the best-selling non-fiction English book of the century, and would rival the best of Dickens in popularity.

In our own day, however, of the several panoptic English intellectuals known as the Victorian sages, Macaulay is the least known. The other sages themselves tended to find his sagacity dubious, his creamy rhetoric slathered over unpalatable ideas. Matthew Arnold made famous the term “philistine” for the triumphalist middle class nullity he found insufferable, who turned his back on the sweetness and light of moral, intellectual, and physical beauty, plighted his devotion to a dim-witted catechism of human perfection, and bet his meager soul on “freedom, on muscular Christianity, on population, on coal, on wealth—mere belief in machinery, and unfruitful.” Arnold called Macaulay “the great Apostle of the Philistines,” with particular scorn for his monumental essay in praise of Francis Bacon. Upon reading Macaulay’s collected essays in 1855, John Stuart Mill derided him as “an intellectual dwarf—rounded off and stunted, full grown broad and short, without a germ or principle of further growth in his whole being.” In Praeterita, John Ruskin, while praising Samuel Johnson, seized the occasion to damn the pseudo-intellectual rabble, who “are just as ready with their applause for a sentence of Macaulay’s, which may have no more sense in it than a blot pinched between doubled paper, as to reject one of Johnson’s, telling against their own prejudice.”

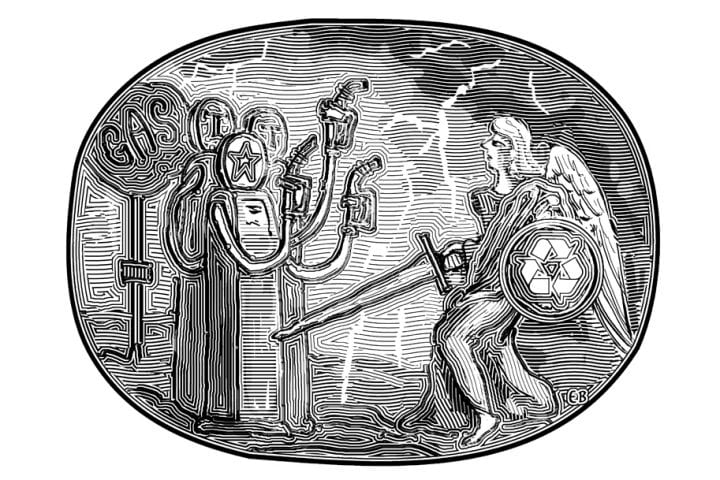

Nearer to our own time, Lytton Strachey, Bloomsbury’s lord high executioner of over-inflated Victorian Unworthies, and perhaps the most influential stylist of 20th-century English prose, whose languid sneering wit snakes along and delivers an injection of lethal venom in every other paragraph, condemns Macaulay as the most influential stylist of 19th-century English prose, and thus the representative of a civilization rightly finished in every respect. In one of his Portraits in Miniature (1931), Strachey writes, “The repetitions, the antitheses, resemble revolving cogwheels; and indeed the total result produces an effect which suggests the operations of a machine more than anything else—a comparison which, no doubt, would have delighted Macaulay.” What really galled Strachey, though, was that for all his “middle-class, Victorian complacency,” Macaulay was nevertheless an unsurpassed master of narrative prose: “Philistine is, in fact, the only word to fit the case; and yet, by dint of sheer power of writing, the Philistine has reached Parnassus.”

Defender of Civilization

What place, then, does Macaulay occupy, or command, in the intellectual life of his time and of ours? Is he useful to us? Is he necessary? Should one even bother?

Politics fervent and noble enriched the household atmosphere of Macaulay’s boyhood. His father, Zachary Macaulay, prominent member of the Clapham Sect, the most influential association of religious social reformers in early 19th-century England, turned his imposing Evangelical mind and will to the movement to abolish slavery in the British Empire. Young Thomas grew precociously aware of the evils great and small to be eradicated from the body politic, and his would always be a politically charged and morally driven intelligence.

After a sterling undergraduate career at Trinity College, Cambridge, he was awarded a Trinity fellowship at 23, but the inadequate income, at a time when his father had lost most of his fortune, drove him out of the academic cloister, looking for a second job, and even a third. Moonlighting, he tried his hand at the law, but failed decisively.

Then, however, Macaulay discovered his métier, when the editor of the Edinburgh Review, the leading British intellectual journal of the time, discovered him, in a lesser publication’s collection of work by recent Cambridge graduates. A long Edinburgh essay on John Milton—those were the days of routine novella-length literary journalism—caught everyone’s attention. As Sir Arthur Bryant wrote in his 1932 biography, “Like Byron after Childe Harold, Macaulay awoke one morning to find himself famous.”

His essays gained him entry to the Whig salons where ambitious young writers verified their brilliance with copious elegant talk. Macaulay was out to impress as the supreme conversational virtuoso; and while some goggled in wonderment as he delivered show-stopping monologues without coming up for air, others found it all a bit much. To refined gentlemen accustomed to decorous convivial chat, Macaulay, for all his genius, could come across as a pushy bore, hopelessly middle class, a climber who didn’t understand protocol.

But the unrelenting flow of gorgeous eloquence served Macaulay well and soon: anyone could see he was a natural for Parliament. In 1830 he was elected to the House of Commons—one might say appointed—as Whig member for the pocket borough of Calne. He entered Parliament just as Tory supremacy was dissolving and the Whigs were the new majority party. In March 1831 he made a lasting mark with a momentous speech in support of the Reform Bill, the epic (though initially tiny) expansion of the British franchise.

Turn where we may, within, around, the voice of great events is proclaiming to us, Reform, that you may preserve…. Renew the youth of the state. Save property, divided against itself. Save the multitude, endangered by its own ungovernable passions. Save the aristocracy, endangered by its own unpopular power. Save the greatest and fairest and most highly civilized community that ever existed from calamities which may in a few days sweep away all the rich heritage of so many ages of wisdom and glory.

Even the Tory leader, Sir Robert Peel, called some passages of Macaulay’s speech “as beautiful as anything I ever heard or read.” At the age of 30 Macaulay was assuming the mantle of defender of civilization. He knew what he wished to preserve of English tradition, and he spoke not so much of the justice of the reformers’ cause as of the peril that failure to reform would visit upon the land: he thought of peaceful orderly days and agreeable evenings in good company, and he feared the mob.

The Reform Bill would pass by a whisker, on a second go-round in 1832. The work of national salvation thrilled Macaulay; the adulation impelled him to work harder and harder. The Whig aristocracy set a permanent place at its table for this audacious young buck from the middle class and for the middle class. Yet all the while the financial needs of Macaulay’s family—his father and unwed sisters, for he never married himself—nagged at him. He needed nothing less than to make his fortune and ensure their comfort—and of course his own.

Audacious young bucks on the make looked to India as their land of hope and glory. Friends pulled strings, and in 1833 a place was arranged for Macaulay in the new Supreme Council of India. With a yearly salary of £10,000—he had been earning some £900 in England—he could be assured that a five-year tour of duty would make him a man of independent means when he returned to England.

Macaulay would always keep in mind the dual aims of British imperialism: bringing the light of progress to places of darkness, while giving the benefactors the opportunity to make themselves rich as lords. The former aim ought not to be obliterated in today’s post-colonial disenchantment with fishy higher motives. Macaulay successfully directed Indian education reform, very decidedly for the best, and he also framed the new penal code, which in a land where widows were burned alive and the original Thugs garroted unlucky travelers does not exactly seem morally presumptuous.

And he did make his Indian pile, so he could live the life he chose upon returning home in 1838. But what should he choose? From India, Macaulay wrote to friends that on his return home he would shun political life and devote himself to writing. When called to action, however, he could not but answer. In March 1839 he began work on his History of England, but in June his writing was brought up short when he was elected M.P. for Edinburgh, and in September his troubles increased as he was appointed Secretary at War in Lord Melbourne’s cabinet. He would bounce between politics and literature until 1847, when he lost his seat in Parliament; taking immediate advantage of his new situation, he focused on writing the history, but in 1852 he was elected to Commons once again and promptly suffered his first heart attack. Somehow he soldiered on, sticking it out in Parliament until 1856, fending off his enervating chronic illness as best he could, laboring religiously on his vast book. Heart failure ended his life in 1859, and cut his work short. The fifth and final volume of his masterpiece would be published unfinished in 1861.

Clear Thinking

But Macaulay’s work does live, having shaped the thought of our own time in ways so telling that his influence is too readily forgotten. He was the most accomplished of the Whig intellectuals, the champions of middle-class liberalism as 19th-century England understood that word, of commercial values shot through with Protestant reasonableness, a species of godliness conducive to, not to say at the service of, worldly success and satisfaction. Whig history as commonly practiced can be too much of a good thing, an unceasing tribute to unceasing Progress, with the emphasis on material improvement, with scant room for the condition of men’s souls, or alternatively with vapid moralizing about the failure of the past to live up to the standards of the present. Although Macaulay relies on the common template, he composes with an uncommon sense of historical complexity and contingency that raises him above the customary faults of his kind.

His 1830 review of Robert Southey’s Colloquies on Society offers rousing proof that modern life is far superior to that of pre-industrial England, and Macaulay makes the case for liberal political economy, which is to say, unadulterated laissez-faire, as the necessary condition of workingmen’s unprecedented decent livelihood. In Macaulay’s view, the poet laureate and retrograde intellectual Southey upholds an ideal of agrarian bounty and comeliness that never in fact existed, and that even if it had existed would not have been half as conducive to the general well-being as “the manufacturing system.” “There is nothing which he hates so bitterly. It is, according to him, a system more tyrannical than that of the feudal ages,—a system of actual servitude,—a system which destroys the bodies and degrades the minds of those who are engaged in it.” Where Southey paints a rural idyll of winsome cottages with Wordsworthian daffodils all about, Macaulay scoffs, countering with such dry matters of fact as the reduction of mortality rates under the new dispensation. “We might with some plausibility maintain, that the people live longer because they are better fed, better lodged, better clothed, and better attended in sickness; and that these improvements are owing to that increase of national wealth which the manufacturing system has produced.” Supremely confident in the justice of his cause, Macaulay cannot resist swaggering some as he unloads on this incapable and unfortunate enemy. “His principle is, if we understand it rightly, that no man can do anything so well for himself, as his rulers, be they who they may, can do it for him; that a government approaches nearer and nearer to perfection, in proportion as it interferes more and more with the habits and notions of individuals.” And Macaulay’s peroration leaves not a wisp remaining of the opposition’s castle in the air:

It is not by the intermeddling of Mr. Southey’s idol—the omniscient and omnipotent State—but by the prudence and energy of the people, that England has hitherto been carried forward in civilization; and it is to the same prudence and the same energy that we now look with comfort and good hope.

So long as government limits the reach of its authority, “by leaving capital to find its most lucrative course, commodities their fair price, industry and intelligence their natural reward, idleness and folly their natural punishment,” the people will take care of themselves, as honorable free men gladly do, whatever the difficulties.

The righteously compassionate among us will consider an author who admits to such sentiments a hotheaded and coldhearted ideologue, devoted to his simplistic guiding precept at the expense of simple humanity, indifferent to the suffering of those crushed under the wheels as the capitalist juggernaut roars into an ever more cruel future. And yet in 1846 Macaulay delivered a powerful speech in support of legislation to reduce the permissible hours of youth labor from 12 to 10 daily, and for six days a week.

I hardly know which is the greater pest to society, a paternal government, that is to say a prying, meddlesome government, which intrudes itself into every part of human life, and which thinks that it can do everything for everybody better than anybody can do anything for himself; or a careless, lounging government, which suffers grievances, such as it could at once remove, to grow and multiply, and which to all complaint and remonstrance has only one answer: “We must let things alone: we must let things take their course: we must let things find their level.”

Macaulay’s compassion is that of the passionate champion of freedom, personal initiative, responsibility for one’s own success or failure, and the profuse benefits that well-run business provides to the entire nation.

The reform that Macaulay proposes is not only righteous but beneficial to commerce, sowing widespread prosperity, reducing class hatred, strengthening the imperial grip, all for generations to come.

Your overworked boys will become a feeble and ignoble race of men, the parents of a more feeble and more ignoble progeny; nor will it be long before the deterioration of the labourer will injuriously affect those very interests to which his physical and moral energies have been sacrificed. On the other hand, a day of rest recurring in every week, two or three hours of leisure, exercise, innocent amusement or useful study, recurring every day, must improve the whole man, physically, morally, intellectually; and the improvement of the man will improve all that the man produces.

There must be more to a working-class life than debilitating work, and here Macaulay responds to the danger that Adam Smith himself warned of, in the very division of labor whose efficiency he extolled. Smith’s concern, and Macaulay’s, echoes in John Ruskin’s lament in The Stones of Venice (1851-53): “It is not, truly speaking, the labor that is divided; but the men:—Divided into mere segments of men—broken into small fragments and crumbs of life; so that all the little piece of intelligence that is left in a man is not enough to make a pin, or a nail, but exhausts itself in making the point of a pin, or the head of a nail.” The well-heeled advocates of liberal political economy join forces on this matter with the godly socialist firebrand. Such agreement is a rarity.

At the same time, it is useful to remember that Macaulay dismissed Charles Dickens’s most angry novel, Hard Times, with a caustic one-liner: “One excessively touching, heart-breaking passage, and the rest sullen socialism.” Macaulay saw Dickens as stoking the indignation that raged even against irreparable evils, while Macaulay himself thought, wrote, and argued as a moderate political man, who recognized which reforms were not only called for but might even be workable. He honored the distinction between government solicitude in the name of decency and government intervention in pursuit of phantoms—of impossible equality and supposed justice. It is a sad reminder of what even the temperate Macaulay was up against that his stirring speech cited above failed to win passage of the Ten Hours Bill—even though he ended by proposing a trial period of 11-hour workdays, in case ten sounded too extravagant. Only a year later did the mercifully reduced hours become law. Whig historians and statesmen are frequently travestied, and sometimes legitimately described, as the henchmen of Progress that never quits and knows no bounds. Macaulay saw history differently from that, and more clearly: not as an unstoppable torrent of human improvement, but rather as an unsteady, intermittent flow, proceeding and receding by turns, as hard-won benefits produced new difficulties that had to be overcome, by hearts and minds often scuffed and worn by evidently endless struggle.

Heroes Worth Having

Here one sees Macaulay’s lifelong theme emerge: what is the truest measure of a civilization, and who are its indispensable men? And he answered his questions simply and clearly: the civilization that lives by the Whig values of freedom and an end to unreason, as promoted by the most convincing Whig intellects. Already in his inaugural essay, “Milton” (1825), Macaulay esteems the greatest poet and ablest political controversialist of an age riven between “liberty and despotism, reason and prejudice.” Yet he admits that the two most respected and most popular British historians, the earl of Clarendon and David Hume, were appalled at the Puritan Revolution and took the side of royalty in this protracted conflict. The immensely influential Hume “hated religion so much that he hated liberty for having been allied with religion, and has pleaded the cause of tyranny with the dexterity of an advocate, while affecting the impartiality of a judge.” Macaulay is certain that Milton got the essentials right where Clarendon and Hume got them wrong—notwithstanding the freshly instituted evils Macaulay inveighed against.

There is only one cure for the evils which newly acquired freedom produces—and that cure is freedom!… The blaze of truth and liberty may at first dazzle and bewilder nations which have become half blind in the house of bondage. But let them gaze on, and they will soon be able to bear it…. And at length a system of justice and order is educed out of the chaos.

Whereas Milton was Macaulay’s 17th-century hero, Samuel Johnson carried the torch of liberty and wisdom for the 18th, though he was in several respects not to Macaulay’s taste: a vehement Tory, an affected and ungainly prose stylist, and a tremulous religious obsessive tormented by his own spiritual unworthiness and the vision of perdition that drew nearer with every passing moment. Macaulay wrote two substantial pieces on Johnson, the first an Edinburgh essay in 1831, the second an Encyclopaedia Britannica entry in 1856. The glowing encyclopedia entry ends with summary praise for “a great and a good man.”

Yet even Johnson had a superior: the parliamentarian and man of letters Joseph Addison, best known today as an essayist: “the just harmony of qualities, the exact temper between the stern and the humane virtues, the habitual observance of every law, not only of moral rectitude, but of moral grace and dignity, distinguish him from all men who have been tried by equally strong temptations, and about whose conduct we possess equally full information.”

Addison’s ennobling tribute to the most virtuous Roman, Cato—which Macaulay ranked in the company of Racine and Corneille, if not with their very best, and well above the other English tragedies of the period—is virtually unknown even as a closet drama, done in by a sententiousness no long-er appreciated. Macaulay provides a valuable corrective to our own rather louche and limited artistic taste, by bringing a play such as Addison’s to our attention: its “moral and intellectual qualities,” like those of Samuel Johnson (who was a warm admirer of Addison), might prove worthy of remembrance and revival three centuries along. It is right and just that Addison’s Cato should inspire such reverence in Macaulay, whose Lays of Ancient Rome honor Roman political virtue at its noblest peak, as in the poem eulogizing Horatius and his comrades at the bridge holding off the enemy onslaught: “Then none was for a party; / Then all were for the state; / Then the great man helped the poor, / And the poor man loved the great.”

Francis Bacon and Modernity

It is the sworn duty of the great man, in Macaulay’s eyes, to help the poor, by which he encompasses the generality of mankind. Macaulay reveres the men such as Cato, Horatius, Milton, Johnson, and Addison, who represent the best of their civilization, and he reserves his greatest praise for those of supreme learning and wisdom who define an epoch and set humanity on an unprecedented beneficial course. His 1837 essay “Francis Bacon” is the work most expressive of Macaulay’s Whiggism: a 100-page assessment of a venal political man who all the same was the most heroic philosopher, the founding father, of modernity. And modern life, based on innovative thought, is an improvement in almost every detail over the richest accomplishments of its predecessors, whether Athenian or Roman or medieval Christian, whether founded upon Platonic, Aristotelian, Socratic, Stoic, or Scholastic teaching.

Two words form the key of the Baconian doctrine, Utility and Progress. The ancient philosophy disdained to be useful, and was content to be stationary. It dealt largely in theories of moral perfection, which were so sublime that they could never be more than theories; in attempts to solve insoluble enigmas; in exhortations to the attainment of unattainable frames of mind.

This obsolete philosophy reigned for millennia, “meanly proud of its own unprofitableness.” The not-so-wise men long gone got nowhere fast and saw to it that mankind would stay there, without hope of improving the general lot. The ancient thinkers did not trouble themselves with the happiness of the multitude; their concern was to make the world safe for philosophy, to make sure that the multitude did not trouble them. Against this gross egotism, as Macaulay sees it, he sets Bacon’s “philanthropia”: “this majestic humility, this persuasion that nothing can be too insignificant for the attention of the wisest, which is not too insignificant to give pleasure or pain to the meanest, is the great characteristic distinction, the essential spirit of the Baconian philosophy.” To think for the pleasure of thinking squanders the incalculable gift of intellect. To think for the good of humanity ennobles the philosopher who comes down to the common level; bending his genius to the needs of ordinary men, as those ordinary men understand their needs, Bacon elevates the vocation of mind to universal service and thus gives it an unprecedented dignity, in Macaulay’s eyes.

Macaulay’s essay on Bacon is a period piece, which establishes the intellectual pedigree for the consuming ambitions of Victorian enterprise: industry, technology, business, empire. If a man as extraordinary as Bacon breaks with the immemorial teachings of philosophy, then the middle-class Englishman has every reason to think very well indeed of himself, as the rightful inheritor of this prodigious mental energy expended for his sake.

Today one need not be a devotee of classical philosophy to look upon Bacon more warily than Macaulay did, as the relief of man’s estate threatens to bring about the brave new world of scientism run amok, with all its alluring monstrosities. For Macaulay, no such prospects clouded his enthusiasm for every discovery that made everyday life less painful, less exhausting, and thus more comfortable, more convenient, more content.

Masterpiece of Whig History

Macaulay’s History of England is the acknowledged masterpiece of Whig history, celebrating the Philistine values that more fashionable intellectuals grind under their heels, retailing the past that prepared the way for the comfortable, convenient, and contented present and for the future bound to be more agreeable still. The work is remarkable for its sense of high political adventure at the gallop and its endless procession of beautiful sentences, but its signal accomplishment is as a moral document, subtle in its character studies of leading men, innovative in its attention to the daily lives of the common people.

Macaulay had a penetrating eye for the nearly limitless variety of moral turpitude in men who craved power and distinction, and he registers the degrees by which one descends into iniquity, much as William Hogarth records A Rake’s Progress in his famous engravings. Among the Restoration politicians of the “most malignant type,” known as the Cabal, Buckingham is perhaps the most contemptible, “a sated man of pleasure,” for whom his political career is an amusement he takes to when all other diversions have been exhausted. Ashley is shrewder than Buckingham, “tim[ing] all his treacheries,” so that he invariably places himself with the faction in power at the moment. And Lauderdale, “under the outward show of boisterous frankness, [was] the most dishonest man in the whole Cabal.”

With such a host of miscreants wielding authority, every sort of corruption became standard procedure:

From the time of the Restoration to the time of the Revolution, neglect and fraud had been almost constantly impairing the efficiency of every department of the government. Honours and public trusts, peerages, baronetcies, regiments, frigates, embassies, governments, commissionerships, leases of Crown lands, contracts for clothing, for provisions, for ammunition, pardons for murder, for robbery, for arson, were sold at Whitehall scarcely less openly than asparagus at Covent Garden or herrings at Billingsgate.

That ordinary Englishmen should suffer the misrule of these aristocratic reprobates incenses Macaulay. His very long chapter on “The State of England in 1685” tells of a time when the Hobbesian state of nature was found in the heart of civilization. “Saint James’s Square was a receptacle for all the offal and cinders, for all the dead cats and dead dogs of Westminster.” The litany of abominations goes on and on, as most Englishmen “suffered what would now be considered as insupportable grievances.” Macaulay notes “the vehement and bitter cry of labour against capital” in a broadside popular at a time of starvation wages. “If the poor complained that they could not live on such a pittance, they were told that they were free to take it or leave it.” This ugly travesty of English freedom must not be taken as boiling subversion on Macaulay’s part. The disgraceful condition of the working poor in 1685 is a foil for the comparative prosperity of Victorian England. Whatever “social evils” might still be found in this modern land of the bountiful forge and smokestack “are, with scarcely an exception, old. That which is new is the intelligence which discerns and the humanity which remedies them.”

The original remedy for England’s innumerable pains was the Revolution of 1688, which placed the Dutch Stadtholder William of Orange on the English throne, as the fundamentals of Whig freedom and justice and prosperity supplanted the tyranny of insufferable popish militancy that was the last gasp of medieval divine royalty:

The Whig theory of government is that Kings exist for the people, and not the people for Kings; that the right of a King is divine in no other sense than that in which the right of a member of Parliament, of a judge, of a juryman, of a mayor, of a headborough, is divine; that, while the chief magistrate governs according to law, he ought to be obeyed and reverenced; that, when he violates the law, he ought to be withstood; and that, when he violates the law grossly, systematically, and pertinaciously, he ought to be deposed.

William’s rule marks the end of unrelenting constitutional broils and the English entry into the European theater as a military power, rival to the magnificent and unendurable tyranny of Louis XIV. But the transition from ancient ways to modern ones is trying, and does not always represent a clear advance. A temporary suspension of habeas corpus is “made necessary by the unsettled state of the kingdom,” and adherents to the old order were not the only ones to protest. “It was the fashion to call James a tyrant, and William a deliverer. Yet, before the deliverer had been a month on the throne, he had deprived Englishmen of a precious right which the tyrant had respected.” The cause of liberty necessarily has recourse to methods—temporary methods, if all goes well—associated with tyrants. Macaulay’s world is that of Machiavellian necessity, and with this awareness Macaulay tells his tale as a Whig historian more subtle and complex than most of that stripe. He relates the gradual, pulsing advance of civilization over the course of centuries that has issued in an age of unexampled liberty and decency, but ever mindful how tenuous and fragile the supreme political virtues can be, and with what violence their hold must be enforced, and how things might have come out differently.

A Necessary Man

Yet upon Macaulay’s death, Matthew Arnold prophesied that the vision of this once golden rival will have no future: “what a fate, if he could foresee it: to be an oracle for one generation, and then of little or no account forever.” Only a corroded civilization could exalt a figure so unworthy to such eminence as Macaulay enjoyed. “He lived in the Philistine’s day, in a place and time when almost every idea current in literature had the mark of Dagon upon it, and not the mark of the children of light.”

But no less impressive a figure than Lord Acton, the great Whig historian of English liberty, in his review of a Macaulay biography in 1863 sees him as an indispensable political thinker, his literary vocation and his public career nourishing each other, and both nourishing the general culture of his time, and of the time to come. Lord Acton predicts that Macaulay’s legacy will be perpetuated “not as that of a statesman who achieved great things, or pursued a great policy, but as the brilliant expression of the political ideas of one of the clearest, most consistent, and most accomplished thinkers of modern times. The interest resides not in action but in ideas.”

Samuel Johnson declared that it is not so important to acquire new knowledge as it is to remember the essentials that one learned long ago and that will always remain true. There is truth enough in Macaulay of which a 21st-century conservative ought regularly to remind himself, and against which a modern progressive would do well to measure his own furiously compassionate super-egalitarian multicultural dogma. Macaulay was a necessary man, absolutely, and his mind lives on in many who have no idea how much they owe to his intellectual imprint. Philistinism too has its poetry, just as it has its philosophy; and never have the two been more happily joined than in the life and work of Thomas Babington Macaulay.