Books Reviewed

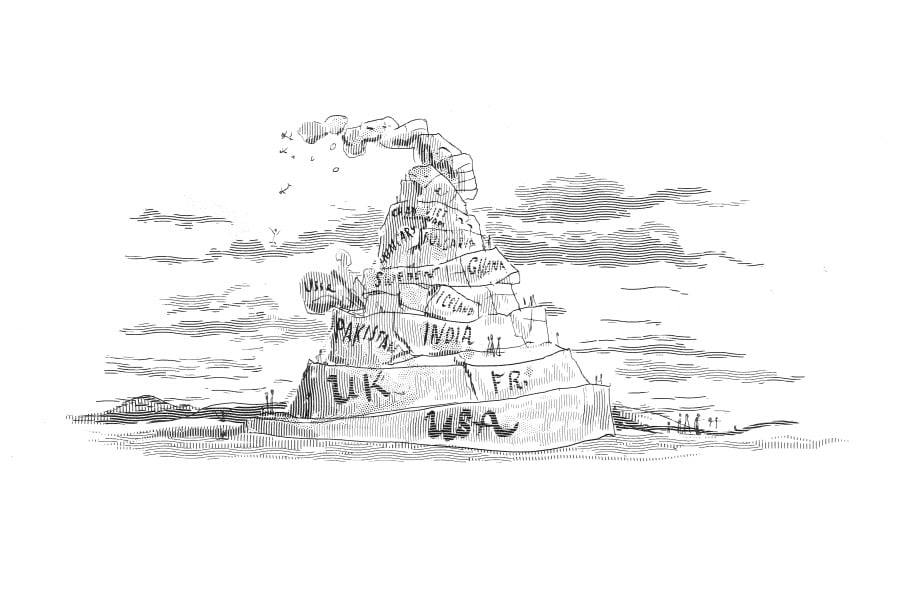

Dore Gold’s Tower of Babble is an invaluable dissection of the founding purposes, subsequent evolution, and current character of the United Nations. A former Israeli ambassador to the U.N., he makes clear early and often his central thesis: the organization was founded with one set of expectations, has dramatically lost its way over the past nearly 60 years, and is consequently in desperate need of systemic reform. As he puts it:

In the biblical story of the Tower of Babel, the nations of the world initially spoke one language but lost their unity of purpose when this changed. In the case of the U.N., member states all spoke the same political language at the beginning, but as new members flooded into the organization, they brought with them their own political languages—that is, completely different values and concepts of international morality.

President Bush has struck a similar theme in each of his recent annual appearances before the U.N. General Assembly. As he reminded the gathered heads of state, diplomats, and international bureaucrats on September 21, 2004:

Both the American Declaration of Independence and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights proclaim the equal value and dignity of every human life. That dignity is honored by the rule of law, limits on the power of the state, respect for women, protection of private property, free speech, equal justice, and religious tolerance. That dignity is dishonored by oppression, corruption, tyranny, bigotry, terrorism and all violence against the innocent. And both of our founding documents affirm that this bright line between justice and injustice—between right and wrong—is the same in every age, and every culture, and every nation.

Actually, both Bush and Ambassador Gold exaggerate the nobility of the U.N.’s founding principles, which perforce were compromises negotiated with the Soviet Union, one of the original allied powers. Still, in order to be a founding member, Gold avers, at least “a state had to have declared war on at least one of the Axis powers.” For this reason, Winston Churchill preferred to call it the “Allied Nations.”

It followed, necessarily, that “the early U.N. could define for itself who was the aggressor and who were the allies resisting aggression.” As the membership changed over time, however—thanks to the combined effects of European decolonization and Soviet imperialism—the majority of votes in the General Assembly fell into the hands of dictators and totalitarian regimes. The new states all too often “wanted international rules that would suit the needs of dictatorships, rather than democracies.” The result was that “the U.N.’s early moral clarity was replaced with a corrosive moral equivalence.” According to Gold, this sea-change was evident as early as 1948, when the first Arab-Israeli war and the Indo-Pakistani conflict over Kashmir erupted. In both cases, the U.N.’s inability to distinguish aggressor from victim contributed materially to the conflicts’ persistence and bloody intensification.

* * *

Gold covers familiar ground in examining how the Soviet Union used its working majority and veto during the Cold War—at best to paralyze the U.N., at worst to imperil freedom-loving nations. The single exception was in response to Communist North Korea’s invasion of the Republic of Korea to its south. Having boycotted the U.N. for its refusal to recognize the Communist conquest of mainland China, the Kremlin found itself unable to block U.N.-authorized military action to defend South Korea.

This was precisely the kind of thing that the U.N.’s founders—at least most of them—meant it to do. But even in the Korean case, the U.N. had failed, Gold argues, because it “had not deterred North Korea from taking offensive action in the first place.” He concludes that Kim Il-Sung and his Soviet master, Joseph Stalin, delighted by the U.N.’s feckless response to the Arab-Israeli and Kashmiri conflicts, had bet that the world body would again fail to act decisively.

Gold attributes the U.N.’s dismal performance in the major post-Cold War crises (notably in Rwanda, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and the second Iraq war) mainly to the organization’s chronic “moral equivalence.” In its “repeated pursuit of ‘impartiality,’ the U.N. actually has taken sides—in effect joining the aggressors and the abusers.” Matters have been made worse by the multiplication of new entities like the politicized International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court.

Lately, this problem has become sufficiently acute that the U.S. military has coined a term for it: “lawfare,” a form of asymmetric warfare waged by relatively weak states in order to constrain the freedom of action of more powerful ones. Gold neglects to mention similar dangers associated with another U.N. convention—the Law of the Sea Treaty, with its own Tribunal—that the Bush Administration unfortunately has urged the U.S. Senate to approve “as soon as possible.”

In light of these realities, Gold urges the formation of a new, standing democratic coalition outside of and operating parallel to the U.N. Such a coalition would “embrace the principles laid out in the U.N. Charter and insist that members of the coalition fully adhere—not just give lip service—to a basic code of international conduct.” As for reform of the U.N., Tower of Babble has few concrete prescriptions, beyond noting that the U.S. should “work within” the organization over the long term in order “fundamentally [to] alter the voting patterns of the U.N. General Assembly member states.” Until such a transformation is accomplished—presumably through changes that make the governments casting such votes more peaceable, democratic, and supportive of freedom—he recommends confining the U.N. to humanitarian work.

The Bush Administration, Congress, and the American people would be well advised to take to heart Dore Gold’s unblinking assessment. What ails the U.N. is not primarily the number of permanent members of the Security Council, bureaucratic inefficiencies, or even the problem of corruption from which Kofi Annan would have us avert our eyes.

What has made the U.N., at its worst, an enabler of repression, aggression, and terror around the world is the dominant influence within it of regimes with an ill-disguised hostility to freedom and to democratic government itself. Unless this aspect of the U.N. can be fundamentally and permanently corrected, the last thing we should want is a stronger U.N.