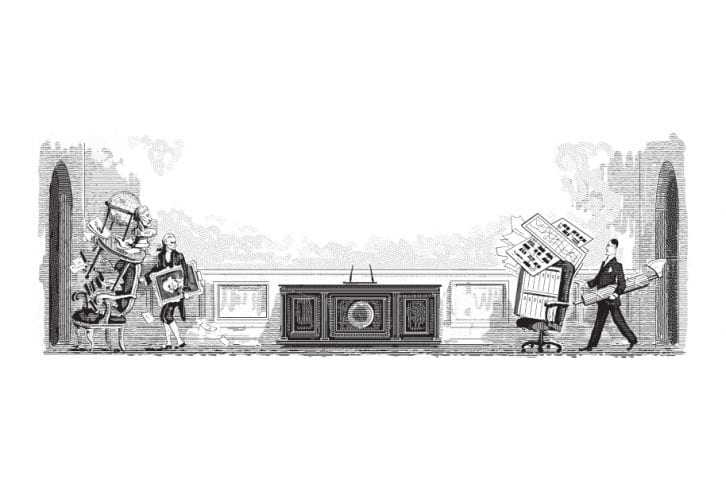

Too often these days, conservatives find themselves reading obituaries and meeting at funerals. Ronald Reagan died in 2004, Milton Friedman in 2006, and now William F. Buckley, Jr., father of the modern conservative movement, has left us, too. And of course these gallant souls were preceded into glory by many others, from Barry Goldwater to Friedrich Hayek. As we mourn our heroes, we can be forgiven for feeling a little like political orphans, suddenly looking around and asking, what now?

American conservatism does seem adrift. Partly that’s the fault of George W. Bush’s incoherent administration, which has disappointed conservatives above all. The Republican primaries, far from restoring the Right’s spirits, exhibited in striking fashion that Bush was no fluke. One hears more and more that the heroic age of conservatism is over.

But is there no hope of revival? Certainly it’s true that conservatism’s founding era is over, and that the Soviet Union’s collapse and socialism’s profound discrediting count as its triumphs. But socialism is a perennial heresy, sure to reassert itself in one statist form or another when the free economy, in its typical oscillations, produces too many billionaires or too many unemployed workers or both. So the defense of the market economy is by no means exhausted.

Besides, its very success generates new problems. In Russia and elsewhere, people assumed that capitalism and freedom would arise immediately and more or less spontaneously after the tyrant’s statue was toppled. They were soon disillusioned. Global capitalism’s very complexity adds new complications. Am I the only one who wishes Milton Friedman were here to explain the global credit crisis?

In fact, the challenges now facing conservatism are in some respects the hardest of all: the deep-seated relativism of elite culture (which infects popular culture, too), and the protean ambitions of the liberal State. But a lot of conservatives would prefer a tidy, unheroic future. Indeed, this was the spirit of most of the Republican contenders for president, who strained to come up with criticisms of the status quo. Mitt Romney, for example, who campaigned (eventually, and tepidly) on the theme that “Washington is broken,” proposed to unleash an army of consultants to come up with an improved business plan for the federal government. Give ’em hell, Mitt!

Mike Huckabee’s scheme to replace the federal income tax with a sales tax was more ambitious, but revealed its impracticability on first inspection. It would have taken a miracle to get it passed, and another to make it work. Ron Paul offered miracle-free but equally gimcrack libertarianism: pretend that the people are longing for smaller government (if only it were that easy), and that war, especially this one against the jihadists, is a government trick. By his own admission, John McCain, so resolute in war, was less focused on the issues of peace.

In spirit and message, the candidates were far from reagan’s clear, bracing declaration that “in this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” You’d think that most of the GOP contenders had no big quarrel with the modern state; they just wanted to run it. Granted, Reagan said carefully, “in this present crisis,” and we’re not in the same crisis anymore. But the Gipper pointed to ways in which the modern state had exceeded its constitutional authority, and had come close to escaping the consent of the governed, and had traduced the moral, religious, and historical grounds of patriotism; and in those respects his indictment remains deeply relevant.

As does Bill Buckley’s injunction that we must resist “the beatification of the state.” He meant that we must defend limited government against the progressives’ drive to unlimit it—to make government and society into The State, and The State into the divine image on earth. Buckley knew that there is something precious and worth fighting for at the root of the American way of life, at the foundation of the Republic: the truth, he wrote, that “all men are equal and born to be free”; that implanted in each one of us is “that essence that separates us from the beasts, and tells us that we were made in the image of God and were meant to be free.”

These soaring truths of American conservatism are not heard as often as they should be, and are not as central as they need to be to the conservative argument against so-called liberalism, which claims to be the source and censor of our rights. We honor our heroes, and Bill was certainly one of mine, not by nostalgia but by emulation. We need to dig deeper the wells that our fathers dug, and take up the work of defending and restoring the Republic in ways that would make them proud.