Books Reviewed

Mark Rudd used to be a famous radical activist, a leader in the turbulent 1960s and ’70s of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and its more radical offshoot, the Weather Underground or Weathermen, and in his own words, a “Jewish-American prince.” In this memoir he endeavors to provide both vindication of and some distance from his youthful beliefs and actions. As the book proceeds it becomes clear that his radical beliefs remain the foundation of his sense of identity, confirming how difficult it is to renounce long-held and widely shared convictions that at an early stage made life meaningful and seemingly heroic.

About two thirds of the book is devoted to an overly detailed reconstruction of Rudd’s actions during the protests at Columbia University in 1968 and his subsequent involvement with the SDS and Weathermen, including the notorious “days of rage” in Chicago—a pointless orgy of violence by the hardcore elements of the movement. Although he landed on the FBI most wanted list, the charges against him were dropped and the supposedly repressive might of the state (“the Machine,” he used to call it) never touched him. In 1980, he became a teacher at a community college in New Mexico, retiring in 2006 to write this book intended to inform and inspire a new generation of activists.

The most interesting question is what exactly made Rudd so enraged at American society, motivating him to devote the best years of his life to radical political activism. Unlike many other ’60s radicals he was not a “red-diaper” baby: his parents were not old leftists or Communists but contented business people, middle-class Jews who appreciated their secure and comfortable life in a New Jersey suburb. Throughout his years underground he kept in touch with them, and they helped him financially; often he felt guilty for causing them sadness and worry on account of his life as a fugitive.

Early in the book he acknowledges that before becoming a radical something bothered him that had no apparent connection with political or social injustice:

something gradually began to feel wrong. I’d be sitting in my freshman English class [at Columbia]…and suddenly I would be overcome by a wave of despair. Confused questions would pop into my mind: Why am I here…pretending to be interested in poetry? Who are these boys sitting next to me in their blue blazers, regimental ties, and pressed slacks? And I also wondered like many an eighteen-year-old guy, why can’t I sleep with every girl I meet?

Such feelings led him to the college counseling service and subsequently to a psychoanalyst whom he later accused of taking care only of rich people, like himself. He abandoned analysis when he became involved with the radicals at Columbia who were ahead of him in diagnosing the connections between the personal and the political. After immersion in political activities his depression lifted. But very little light is shed here on the nature of the connection between the early, seemingly non-political depression and his political awakening. At the height of his involvement he and his fellow conspirators “determined that there were no innocent Americans, at least no white ones…. Universally guilty, all Americans were legitimate targets for attack.”

Radical activism expressed in demonstrations and occupying campus buildings satisfied his longing for community:

The energy was electric…. The atmosphere in the occupied buildings [at Columbia] was charged…. A strange, chaotic, and loving new life-form had spontaneously erupted…. The term ‘commune’ was joyously seized upon…as a symbol of a new, collective future.

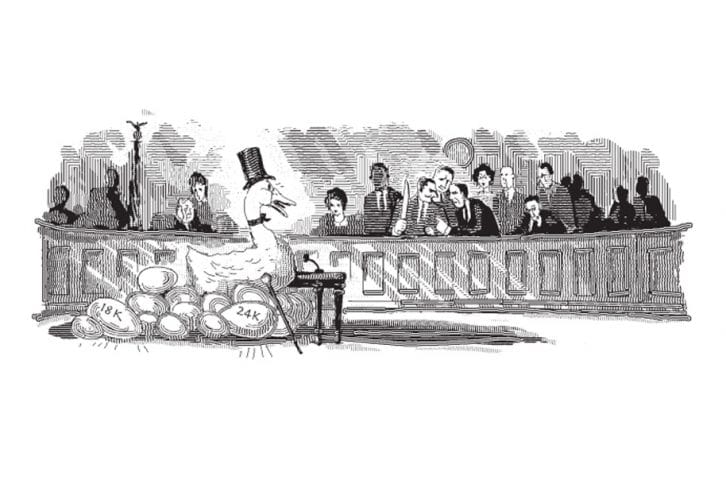

There were also egocentric gratifications: “The lights would then come up, and there I’d be, the star of the movie, standing at the podium…to receive the thundering applause and adulation of the crowd.”

* * *

Several developments undermined his commitment, leading him to surface after seven years of underground life. There was vicious, dogmatic infighting between different radical sects, which accomplished little notwithstanding increasingly strident rhetoric and acts of political violence. In addition, the end of the Vietnam War drained the protest movement’s energy. The Revolution was not about to occur, and “the armed liberation struggle” seemed increasingly pointless; “trying to prove ourselves through violence” lost its appeal. No longer part of the Weather Underground, he strongly disapproved of the organization’s 1981 Brinks robbery and the associated murders. Yet he confesses, “I loved these people [who committed the Brinks murders], they were my intimates, and what we’d started together they had merely continued straight to the tragic end.”

The reunion of 400 former Columbia University activists in 2008 appeared to strengthen his self-congratulatory impulses:

The old feelings of being caught up together in something so historic and larger than ourselves flooded back, lifting us to that delirious and scary moment when we first acted on our principles and tasted what it was like to take charge of our lives…. We introduced ourselves to each other and found that all the people present had gone on…to create lives that more than fulfilled the promise of what we started in those buildings.

During the same reunion, “Ted Gold was honored as a great organizer….” This was the same person who blew himself up by accident while assembling a large bomb filled with nails intended to be detonated at a dance of military personnel in Fort Dix, New Jersey. In his acknowledgments Mark Rudd salutes his “old comrades” including Gold who either blew themselves up during bomb-making or were incarcerated for murdering the Brinks guards. In the final analysis, good intentions and the supposed idealism carry greater moral weight with him than their murderous intentions and actions.

Although Rudd has come to reject the violence of his comrades (and his own support for it), he cannot bring himself to reflect on the connections between this violence and the ideals that provided justification for it.