A short two years ago, the Democrats basked in the glow of their dynamic new president, elected by their largest popular-vote margin since Lyndon Johnson in 1964, accompanied into office by a fiercely Democratic House of Representatives and a veto-proof Democratic Senate. A long two years later, after the party in power had delivered prodigious deficits and debt, relentless 10% unemployment, and the folly of Obamacare, the voters threw a little Tea Party and heaved scores of Democratic legislators and 400 years of seniority into the drink.

What had seemed to many liberals the beginning of a Democratic electoral realignment—40 fat years of bigger, more ambitious government—ended in what President Obama called a shellacking. (Shellac [verb, slang]: to beat somebody repeatedly with hard blows; to defeat somebody easily or decisively.) What had looked to Republicans like the beginning of a long exile proved a short interlude leading to GOP control of the House, tidy gains in the Senate, and historic increases in its number of state legislators and governors. These Wilderness Years, from 2006 to 2010, didn't allow for much wandering. One wonders if the party actually has learned its lesson, or will soon be longing again for the fleshpots of Egypt.

The GOP has been here before, after all. In many ways the midterm election is a familiar story of American voters' backlash against the Democrats' undivided control of government. Four times in recent political history the Democrats have held sway simultaneously over the House, the Senate, and the presidency. LBJ ushered in the Great Society after his 1964 landslide buried the Capitol in Democrats, Jimmy Carter frittered away his party's control of all three branches from 1976 to 1980, Bill Clinton tried to pass Hillarycare during his turn at unified Democratic control from 1992 to 1994, and Obama had two years to try to transform America. In every case the public deeply, and quickly, regretted its decision to entrust the Democrats with undivided government. And in the elections of 1966 and 1968, 1980, 1994, and now 2010, the voters executed an about-face.

Conservatives like to say America is "a center-right country," and Gallup confirms that conservatives enduringly outnumber liberals. But this center-right country has the strange habit of going on a three-branch Democratic bender about once a decade. It leaves a nasty hangover, with plenty of revulsion at the senseless, hurtful, and expensive misadventures we get into. Still, we keep doing it, and only once in all those years did the people in their wisdom entrust the Republicans with undivided government—during George W. Bush's term. That experiment ended in 2006. There's little reason to conclude, then, that the midterm repudiation of the Democrats prefigures a lasting endorsement of, much less a new electoral majority forming around, the GOP. Overall, the situation seems like the post-1968 norm that political scientists call dealignment: the public doesn't seem willing to trust either party with undivided control of the government for very long.

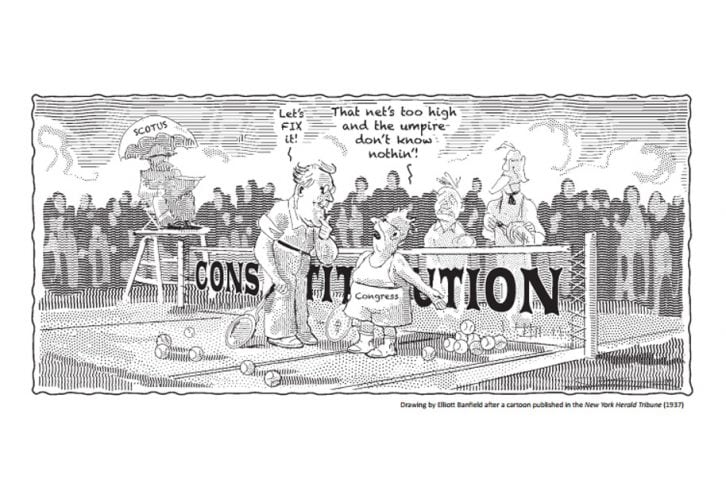

Nonetheless, two new facts obtrude themselves into our political calculations. One is the Tea Party, the other America's enormous deficit, debt, and unfunded liabilities. The Tea Party has not only energized the Republicans, it has given them a new purpose: to cut government back to constitutional size. The draconian cuts some of the Tea Partiers have in mind remind me of the late Joe Sobran's blithe declaration, "Anything called a program is unconstitutional." The problem is that such freewheeling libertarianism soon runs up against the habitual bias of American conservatism—the aversion to sudden, far-reaching, and unnecessary change, felt by lots of people who aren't card-carrying Republicans. Successful right-wing enterprises, like the rebuke of the Democrats in this election, are usually compounded of these two kinds of conservatism. Rand Paul and the Tea Partiers have announced bracingly that they're here to take back their government; but what do they plan to do with it once they've got it back? It won't be easy to exert constitutional control over it, and in that endeavor they'll need both a more nuanced grasp of the Constitution and popular support, too.

Here the other new fact comes to bear. The financial cataracts of our day may sweep everything before them, including the aversion to change. California, Illinois, and New York are insolvent or likely soon will be, harbingers of national distress if spending continues unabated. In the end, conservatives may have little choice but to adapt the American social contract to help foster a new, more responsible era.