Donald Trump and the Republican Party had a triumphant Election Day, gaining ground in all parts of the country and among almost all voting sectors. He won all seven of the ballyhooed swing states, by comfortable margins except in the blue-wall states of Wisconsin (where his margin of victory was 0.9%), Michigan (1.4%), and Pennsylvania (1.8%). Still, he won all three blue-wall states twice—in 2024 as in 2016—something no Republican had managed since Ronald Reagan. Trump regains office alongside a Republican-controlled Senate and House of Representatives, too, the trifecta of what political scientists call “undivided government,” not enjoyed by Republicans since the first two years of his own first term.

President Reagan never enjoyed the luxury of having both legislative houses under friendly partisan control at the same time. Part of what made his victory in 1980 such a breakthrough was the unexpected twelve GOP senators who rode in on his coattails. They restored Republican control of the Senate for the first time since the 1954 election. They lost it again only six years later, in the election of 1986. The party never controlled the House of Representatives under Reagan, though enough conservative Democrats held office to lend the GOP an operational majority sometimes. Nonetheless, the Age of Reagan, as Steven F. Hayward called it in his epic two-volume life-and-times of the Gipper, proceeded more or less smoothly despite the liability of facing divided government in Washington, D.C.

That had something to do with the dimensions of Reagan’s victory in 1980: he won the popular vote with 50.7%, which sounds wan until you consider he had to battle not only Jimmy Carter (41%) but also a strong third-party candidate in John Anderson (6.6%). Without any strong third parties in 2024, Donald Trump won the popular vote (some of it is still being counted) by a slightly lower percentage (50.0%). Reagan’s victory in the Electoral College was hugely impressive, 489 electoral votes compared to Jimmy Carter’s 49. Reagan won every state but five—Minnesota, Georgia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Hawaii. By contrast, Trump in 2024 earned a solid 312 electoral votes from 31 states, compared to Kamala Harris’s 226 from 19 states and the District of Columbia. Trump’s margin, though laudable, falls about in the middle of the pack, historically; lower than Barack Obama’s for example, in 2008 (365 electoral votes) and 2012 (332).

The Age of Trump?

By the numbers alone, therefore, it is difficult to tell if America stands on the threshold of a historic political realignment—the Age of Trump. Patrick Ruffini, the Republican pollster and political analyst, pronounces boldly, “The realignment is here.” On his blog, he proffers as evidence “the first GOP popular vote win in 20 years,” though as the votes are tallied that may slip below a majority; the big shifts in the “educational and class makeup of the parties”; and the Republicans’ capture for the first time “of both low-education and low-income voters,” which he calls “a thoroughgoing working class realignment.” But then he explains that “2024 was as much a ‘realigning’ election as 2016,” which was certainly not a textbook realigning election. Trump’s breakthrough in 2016 was stunning but it did not lead to the GOP becoming the national majority party. The Democrats won back the House of Representatives in 2018, the presidency in 2020, and the Senate in 2020-21. Unless Ruffini is being ironic about 2024 being “as much a realigning election as 2016,” he seems actually to be making a different and more plausible point—more cautiously expressed in his 2023 book, Party of the People, that a national realignment may have begun, but still has a considerable way to go, before it can be confirmed and added to the history books (see William Voegeli’s “Life of the Party,” Spring 2024). It will take at least two or three more electoral cycles to establish, for instance, that the Republicans will be able to retain and expand their (now quite narrow) margins of control over the House and Senate. Although it is always tempting for politicians and analysts to define realignment downward, absent such a dominant legislative record, the GOP will not look like the majority party familiar from American history—the Democrats before the Civil War, the Republicans after it, the Democrats during and after the Great Depression.

Nonetheless, something does feel different about the 2024 cycle. For one thing, this is Trump’s third election in a row as the presidential nominee of his party. It is highly unusual for a major American political party to entrust its nomination to the same candidate more than twice. In recent decades, Richard Nixon is the only other example of a three-time nominee, though his candidacies (1960, 1968, 1972) were not successive like Trump’s. Trump won narrowly in 2016 (about 80,000 votes across three states made the difference), lost narrowly in 2020 (about 40,000 votes in three states separated him from Joe Biden), and won commandingly this time around. His first two elections in effect posed the question—which was the anomaly, Trump’s winning or his losing? This year looks to have settled that question. Two wins now, a narrow and a big one, will probably set the parameters of his place in history. Only he and Grover Cleveland have managed to retake the presidency after losing it for a term. In particular, Trump’s peaceful and sweeping second victory—and what he does with it—gives him the chance to reduce the lingering infamy of the January 6 riot at the Capitol as the culminating and telltale moment (as his detractors insist) of his political career.

After his victory in 1980, Reagan still had the constitutional option to run again, which he did, racking up an even greater margin of victory in 1984 (an astounding 525 votes in the Electoral College and 58.8% of the popular vote). Unless the American people repeal the Constitution’s 22nd Amendment, the 2024 presidential election will be Donald Trump’s last. Everything he hopes to accomplish as president he has to do over the next four years. At 78, he is also the oldest person ever elected to the presidency. He does not want to accompany Joe Biden in future schoolchildren’s dim recall of those “elderly presidents” of the early 21st century. To put it ungraciously, the constitutional and the biological clocks are ticking. The speed and decisiveness of Mr. Trump’s current presidential transition process are likely spurred by these looming countdowns.

To his enemies’ consternation, Trump has made himself the dominant political figure of the age not only in the United States but also—and not metaphorically, merely—in Europe and elsewhere. He hasn’t accomplished this by persuading his critics with the eloquent words and deeds of a classic statesman, but by dominating the imagination of friend and foe alike (see Christopher Caldwell’s “Speaking Trumpian” in this issue). They can’t get him out of their heads, which is the way he likes it. He monitors the Zeitgeist with all its contradictions and tensions. His task, so far at least, has been more to enflame and illuminate these tensions than to resolve them; to expose the growing illegitimacy of American political establishments, Democratic and Republican, rather than to found new ones to take their place. Perhaps the significance of this election, however, is that, like the contractor and real estate mogul he once was, Trump has cleared the ground as well as he can and is about to begin the construction phase of his legacy.

The defining moments of the 2024 race were a mixture of political exposés of his opponents and glimpses of a new majority party aborning. The debate with his then-opponent Joe Biden, as my colleague Bill Voegeli argues in this issue, knocked off the rose-colored glasses through which the Dems and the media had viewed Biden hitherto, and had insisted the public view him, too. Suddenly, the emperor stood revealed as non compos mentis, not by anything Trump said, though he had some good lines, but by Biden’s own, sad difficulties—the “flight of ideas,” as neurologists call it. Then a month later came the first(!) assassination attempt against the former president, and his gutsy, fist-pumping rise from the podium floor in Butler, Pennsylvania. The contrast between the two men, between the setting and the rising sun, was unforgettable. Though it took him and his party a while to admit it, Biden was already an ex-president. The shameful failure of the presidential-security establishment was also clear for everyone to see.

Fries with That?

The most delicious moments of the campaign came near the end, when Trump appeared working at a McDonald’s franchise and a few days later, wearing a high-visibility emergency vest and climbing into the cab of a garbage truck. (Biden had dismissed Trump’s supporters as “garbage” a day before. He didn’t mean it, he pleaded, and I almost believe him.) His critics dismissed these appearances as stunts, which they were, but the most memorable, amusing, and politically revealing stunts since Calvin Coolidge was photographed wearing an American Indian headdress. (It was a gift to him for signing a law granting U.S. citizenship to Native Americans—another voting bloc that Trump won, incidentally.) If Kamala Harris had showed up at a McDonald’s, despite or precisely because she had claimed to have worked at one as a young woman, though which one she could not say, the stunt would have flopped and been mocked from coast to coast—as surely as Michael Dukakis’s notorious ride in a tank in 1988. A well-known consumer of McDonald’s fast food who even served it in the White House, Trump looked right at home working the french frier and the drive-thru window.

Perhaps the most striking graphic of the election was CNN’s map of the United States, showing a county-by-county breakdown of the presidential vote tally. Each county was indicated by a small red or blue mountain (or Christmas tree, if you’re thinking seasonally and don’t mind the wrong colors), the size varying by the percentage change in the vote for the winning party since 2020. It displayed, at a glance, the dynamic political topography of the country. New, unexpected peaks appeared, colored red, and whole mountain ranges upthrust by the tectonic electoral forces at work. CNN reported that of the almost 3,250 counties or their equivalents in America, at least 2,650 shifted more Republican and at least 279 turned more Democratic. That is, almost ten times as many counties voted more Republican than voted more Democratic—a red shift you didn’t need a telescope or a spectrometer to notice. In astronomy, a red shift generally indicates the object is moving farther away from the observer. In politics in 2024, it meant the voters were moving farther away from the Democrats.

Virtually the whole country shifted to the red, as Patrick Ruffini and other observers have remarked. Deep blue states like California and New York provided millions more votes for Trump than he’d received previously, helping him to claim a popular majority. He turned Long Island red, winning both Nassau and Suffolk counties. Florida, once a swing state, swung no more, guarded by medium-sized red mountain ranges up and down its Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Trump took Miami-Dade County handily. Up and down the Rio Grande, at the southern tip of Texas, towering, skiable red peaks expressed the massive Republican shift in these solidly Hispanic, formerly Democratic strongholds. Even the Blue Ridge grew redder, and new Appalachian-sized hills sprouted from Tennessee through western New York State and all the way to Maine.

Maps cannot tell us, of course, why the red shift was so widespread. Were Americans repelled by the Democrats and their programs, or attracted by the Republicans and their promises? We know from county and state voting registrars that the Democrats’ registration figures had eroded in many states during the Biden years, especially the battlegrounds—in Pennsylvania, for example, the Democratic edge from 2020 to 2024 declined from about 686,000 to 286,000 registered voters; in Arizona, the GOP’s edge increased from 94,000 to 295,000. For whatever reason, history was being made. Polls indicated that a greater share of the electorate identified as Republican than as Democrats, for the first time since the New Deal—almost a century.

Kamala’s Red Shift

The Democrats’ effort to build a broader coalition of Resistance to Donald Trump than they had assembled in 2016 and 2020 failed spectacularly. They lost ground almost everywhere (the counties around Atlanta were an exception). Kamala Harris faced a dilemma. She could not run as the designated successor to Joe Biden’s deeply unpopular administration, but she could not afford to repudiate it, either. The term “Biden-Harris Administration” dropped from sight except as a Republican talking point. She declared her independence from him quietly and indirectly, by stressing different issues and above all a different mood to her campaign. In so doing, she also in effect declared independence from her own 2020 rhetoric and campaign pitches when she was running as Biden’s fresh-faced vice-presidential pick. The change went largely unnoticed, because who remembers what a vice-presidential nominee says, anyway?

Regardless, the change marked Harris’s own kind of red shift, months in advance of the election. When in 2020 she accepted her party’s vice-presidential nomination (in those COVID days, Harris spoke from the empty Chase Center in Wilmington, Delaware), she noted the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which gave the vote to women. She hailed in particular the “black women” who helped secure that victory and yet, long after its ratification, had still been prohibited from voting in the Jim Crow South and elsewhere. She connected these injustices to the COVID pandemic and its differential effects. While “this virus touches us all,” she said, “let’s be honest, it is not an equal opportunity offender. Black, Latino, and indigenous people are suffering and dying disproportionately.”

“This is not a coincidence,” she argued.

It is the effect of structural racism. Of inequities in education and technology, health care and housing, job security, and transportation. The injustice in reproductive and maternal health care. In the excessive use of force by police. And in our broader criminal justice system.

As the vice-presidential candidate, in short, she was in full progressive mode, echoing her running mate’s frequent campaign speeches condemning “systemic racism” as the deepest cause of America’s ills. She brought up George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, too. America was very far from being that “Beloved Community” of justice and kindness that “our parents and grandparents fought for.” But it was that same “vision” that made “the American promise—for all its complexities and imperfections—a promise worth fighting for.”

Fast forward four years to Harris’s speech in Chicago accepting her party’s presidential nomination. Gone was the emphasis on women and black women as the key to American history and identity. She presented herself as the proud daughter of two immigrants, and as a proud citizen of “the greatest democracy, in the history of the world,” and indeed “the greatest nation on Earth.” Harris pledged “to fight for this country we love…and to uphold the awesome responsibility that comes with the greatest privilege on Earth. The privilege and pride of being an American.” In place of 2020’s “complexities and imperfections” of the American promise and the enduring reality of “structural racism” throughout American history and society, Harris promised in 2024 to honor and “to hold sacred America’s fundamental principles.” Which apparently were not so bad, after all.

Although not strictly contradictory, the two speeches differed profoundly in tone and in her evaluation of America. She abandoned all the standard woke or progressive critiques of her racist, sexist, cruel country, based on its endemic oppression of identity groups, for a more centrist, middle-class, openly patriotic appeal. She shifted red, in effect. That’s the unacknowledged source of her politics of “joy,” which dominated the initial months of her run for the presidency. Even when it came to abortion, the feminist cause she emphasized throughout her campaign, she talked about it less as a requirement of women’s radical autonomy or equality and more as a violation by government (headed by men, to be sure) of women’s “reproductive rights,” as though she were lodging a libertarian complaint against Big Government’s intrusion on private property. (Leave aside her use of the pregnant term “reproductive freedom” for what is more accurately non- or anti-reproductive freedom.)

Kamala’s red shift served an obvious purpose: she wanted to win. She and her advisors sensed rightly that woke orthodoxy or even Biden’s shouted (or whispered—he had only two volume settings) version of it, warning tediously that Trump imperiled “our democracy,” was not a winning strategy. It was this new moderate Kamala she displayed in her presidential debate with Trump, whom she made fun of as weird and unserious rather than demonic. This was also cool Kamala, “brat” Kamala, confident about America and excited to be ushering in its happy green future. It sounded like a good strategy, but it didn’t work.

One reason it didn’t was that though the public didn’t recall or care what she had said in her 2020 acceptance speech, they did care, once they were reminded by Trump and the news media, about her eager endorsement in 2019-20 of many far-left progressive policies. “Medicare for All,” Bernie Sanders’s expansive plan to one-up Obamacare; the right to government-paid sex-change operations for prison inmates and even illegal immigrants in prison; a ban on fracking—she had once endorsed all of these trendy panaceas, and more. In 2024, alas, they were trending no longer. What to say about them? There were too many to disguise or deny. Best then to say as little as possible. The usually voluble Harris adopted an unnatural strategy of obmutescence. She would say merely that these old positions were no longer valid—she had changed her positions—but refused to say why.

Even the sternest questioning by the press, for instance, by the estimable Bill Whitaker on “60 Minutes,” failed to elicit more from her. He asked her directly,

You were against fracking. Now you’re for it. You supported looser immigration policies. Now you’re tightening them up…. [P]eople don’t truly know what you believe or what you stand for.

To which she replied,

I believe in building consensus. We are a diverse people…. And what the American people do want is that we have leaders who can build consensus where we can figure out compromise and understand it’s not a bad thing as long as you don’t compromise your values.

But Whitaker was asking, in effect: What are your values…?

It was as though the only thing she remembered from her days as a prosecuting attorney was that defendants have a right to remain silent, and that anything you say can and will be used against you…. So she said almost nothing.

As a campaign strategy this approach soon reached the point of diminishing returns. And in the final month or so before the election Harris found an issue to talk about that had very little to do with compromise or joy. She reverted more or less desperately to Biden’s favorite theme: Trump is Hitler.

Sitting Down with Hitler

And yet, several days after the election, there were Joe Biden and Donald Trump sitting together in the Oval Office, smiling and shaking hands. Biden addressed Trump as “former president” and “president-elect” and “Donald,” looked forward to a “smooth transition” and offered to “do everything we can to make sure you’re accommodated.” Afterward, the two men, joined by staffers, chatted for two hours.

Would you shake hands with Herr Hitler? Would you promise to do everything possible to accommodate him in his new job? What was Biden thinking, always assuming he was thinking?

From a certain point of view the “smooth transition” is a hallowed American tradition, a tribute to the continuity of constitutional democracy in spite of our frequent, and often bitter, partisan disagreements. That tribute depends, however, on the presumption that both parties, in honoring constitutional democracy, are speaking of the same phenomenon, the same Constitution, the same democracy. Thomas Jefferson captured the presumption brilliantly in his First Inaugural, in 1801, coming after a particularly divisive decade of political conflict. “But every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle,” he assured his fellow citizens. “We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans—we are all federalists.”

Are Americans in 2024 still “brethren of the same principle”? As Jefferson implies, though not every difference of opinion is a difference of principle, some differences of opinion are.

This was the same Joe Biden, after all, who had denounced “Donald Trump and the MAGA Republicans” as representing “an extremism that threatens the very foundation of our republic.” They are “a threat to this country,” he said at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, because they “do not respect the Constitution…do not believe in the rule of law…[and] do not recognize the will of the people.” Biden told the Democratic National Committee (DNC) that “the extreme MAGA philosophy” is “almost like semi-fascism.” In her 2024 acceptance speech, Harris said her opponent “wants to be an autocrat” and indicted “his explicit intent to jail journalists, political opponents, anyone he sees as the enemy.” The key to his autocratic longing, she explained, was “to pull our country back into the past.” She vowed, and the DNC audience chanted enthusiastically with her, “We are not going back!”

“Politics is tough,” Trump told Biden in their meeting. “And it’s, in many cases, not a very nice world, but it is a nice world today.” He was being gracious. Precisely because it is a tough world, American politicians used to go out of their way to be polite and, formally at least, proper to one another, knowing that on a different occasion they may be expected to denounce one another as fascists, Communists, and other sorts of un-American malefactors. Trump occasionally attacked Biden and Harris in such terms, too. But it’s unusual to make such denunciations the explicit and overarching theme of a whole presidential campaign. Yet this was Biden’s opening and Harris’s closing message, and they never strayed far from it.

To an unusual degree, each party in 2024 accused the other of being a threat to democracy and the Constitution. They meant something different by that, though. As progressives, whatever differences they may have had, Biden and Harris tended to agree that progress is the natural tendency of events, that there is an inherent direction to history which is onward and upward, toward a state of ever greater freedom, equality, and justice, which state they call “democracy.” When anything obstructs that progress and threatens to “turn back the clock,” that tendency is anti-democratic, regardless of how many people voted in favor of it. Progressives expect their reforms to be permanent. Else how could they know they are on the right side of history?

The Obama Prize

Thus progressives tend to operate in a permanent mood of brinkmanship and hyperbole. They suspect any conservative initiative, no matter how moderate or marginal, from cutting tax rates to reducing illegal immigration, to be a stalking horse for a radical abolition of the modern state, with all of its government-created rights. For an unmitigated return to the past, before progressivism; which they imagine means before progress, not realizing how much progress, and actually how much of the most valuable progress, took place before their sect was born. So their typical overwrought metaphor or, more exactly, synecdoche for the past is—Hitler.

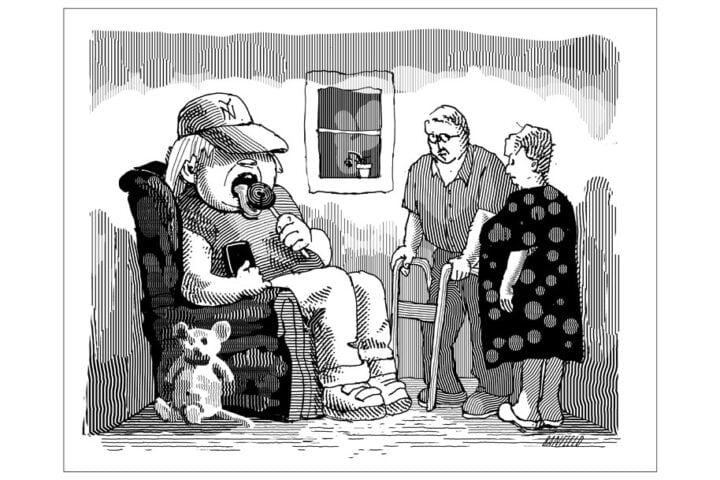

Yet in sober moments even Biden and Harris must recoil slightly at the ridiculousness of this. Several political cartoonists, in fact, imagined the candid moment in their private White House chat when Biden smiled broadly, leaned over and, still sore from how his party had forced him out of the race, whispered to Trump, “You know, I voted for you, too.” I like to think Biden wanted to confess that…even if he didn’t.

When Barack Obama made famous the distinction between history’s right side and wrong side, he implied that the former not only deserved to win but that it would win; it would win because it deserved to. Otherwise, he might have been accused of mere idealism, or wishful thinking. Likewise, the wrong side of history, say, human slavery, consists of losers who defend injustices destined to fail or expire. The purported link between what ought to happen and what will happen is essential to this kind of historical assertiveness. Their confidence in the goodness of the future, their secret or visionary knowledge of what is to come, is the root cause of every progressive elite’s sense of superiority to those who do not know the future, namely, the people, and the politicians who favor the people.

When Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt first championed this new progressivism in American politics, they were confident it rested on nothing less than the truth, as discovered by the new sciences of politics and economics then settling into America’s colleges and research universities. Hardly any 21st-century progressives retain that confidence or continue to believe in progress as an inherent and inevitable historical feature. Even, or especially, Barack Obama—the most thoughtful of its recent political leaders—who showed how to revive progressivism by regarding history as an object of human will rather than of reason or science. He taught progressives they had to will the future they longed for into existence, not only by the usual political means but also by manipulating “narratives” about it told to themselves and their followers, even as he had manipulated the story of his own life in his postmodern autobiography, Dreams from My Father (1995). In other words, the distinction between the right and the wrong side of history may not be strictly true, after all; but it is a good story that could inspire many heroic progressive thoughts and deeds. It ought to be true. But only our resolve can make it “true.”

But Obama’s subtleties are too rarefied for most Democratic politicians. They sensed, however, the crumbling foundations of progressivism and of their own belief in it. So, for several decades now they have propped up those foundations with a new argument from a different combination of social sciences, especially demography and sociology, telling themselves that what would assure liberal progressivism’s victory was not History with a capital H but the “emerging Democratic majority,” to use Ruy Teixeira and John Judis’s phrase from their 2002 book of that title, since questioned severely by them in their new and better book, Where Have All the Democrats Gone? (2023). They predicted that new groups within the Democratic coalition, especially professionals, single women, and minority voters, would augment or displace the old New Deal groups and result in a new national Democratic majority. This “coalition of the ascendant” crashed and burned, however, in the 2024 election. The woke superciliousness that accompanied and helped to justify its ascendance went down with that ship, too.

Though he didn’t use that demographic argument in his speech to the DNC in Chicago, Obama still looked forward confidently to building “a true Democratic majority.” Someone ought to endow a prize and name it after Obama—a prize for being painfully out of touch with your own country. He should receive the inaugural trophy. He could display it alongside the Nobel Prize he got in 2009 for bringing peace to the world. Trump and the MAGA Republicans are now in the process of assimilating working-class voters, including young blacks and Hispanics, supposedly elements in that “true Democratic majority,” into a new Trumpian movement that may form, in time, a new Republican majority party.

Consider Hispanic voters. Exit polls showed Trump winning about 55% of the Latino male vote. CNN reported a 42% swing toward the Republicans from 2016 to 2024. And it wasn’t just among men. Support for the Democrats among Latinas, according to CNN, dropped from a 44% advantage in 2016 to a 22-point advantage this year. The Los Angeles Times interviewed some of Trump’s Latino supporters. “Why am I for Trump?” asked Tomas Garcia, who supported him in 2016, 2020, and 2024. “Because I’m an American first of all.” The 70-year-old’s great-grandparents emigrated from Mexico. “Hispanics are about the American dream,” said Abraham Enriquez, 29, who was raised by the children of Mexican immigrant parents in west Texas. “Trump being a billionaire from New York, with a beautiful family and a beautiful wife, as a young Hispanic man, that is the American dream, that is what you one day want to be like.” Michael Fienup, an economist who studies Hispanics, commented, “Latinos are hard-working, they’re self-sufficient, they’re entrepreneurial, they’re patriotic, they’re optimistic. Guess what? Those are fundamentally American characteristics.”

“This campaign has been historic in so many ways,” Trump said in his victory speech on election night.

We’ve built the biggest, the broadest, the most unified coalition. They’ve never seen anything like it in all of American history…. They came from all corners, union, non-union, African-American, Hispanic-American, Asian-American, Arab-American, Muslim-American. We had everybody and it was beautiful. It was a historic realignment, uniting citizens of all backgrounds around a common core of common sense. You know, we’re the party of common sense. We want to have borders. We want to have security. We want to have things be good, safe. We want great education. We want a strong and powerful military, and ideally we don’t have to use it…. But this is also a massive victory for democracy and for freedom. Together, we’re going to unlock America’s glorious destiny.

Trump has his own style of hyperbole, of course. But notice how his differs from the Democrats’. Conceiving of their own party as being on the right side of history, and the Republicans as ensconced firmly on its wrong side, the party of the glorious future versus the party of the discredited, oppressive, immoral past, makes it very difficult for today’s progressives to admire the American character and the American dream. Trump feels no such reservations or doubts. For all his rough edges as a candidate and a human being, he thinks of Americans as a beautiful people based on a beautiful set of commonsense ideas. Perhaps that’s why he is on his way to building a new majority party, a truly ascendant coalition, brethren of the same principle.