The male, we are told, is fundamentally flawed. Not in an “original sin” sense, which might counsel resignation or charity. No, he is more like a Superfund site: something that urgently needs remediation, lest the whole community be poisoned. For that, you will need a sexual equivalent of the Environmental Protection Agency.

The good news—from this perspective—is that “male,” like “female,” is entirely a social construct. When gender is understood as an arbitrary product of human will, it invites the willfulness of people irritated by the way men and women actually live and feel. Sexual difference is seen not as a given, and certainly not as a gift to delight in, but as a problem to fix. There is no reason we cannot realize this vision of fixing, if only we are willing to free ourselves of outmoded ideas—for example, that old canard that the coercive powers of the state, and of its deputized franchisees in corporate H.R., should be in any way limited.

What kinds of male predilections should no longer be permitted? Should we jettison such stereotypically male behavior as coal mining and sanitation work? How about the lineman who scales a pole during an ice storm to restore power? Perhaps we need to be rid of those who man the Bering Sea fishing fleets (and, in doing so, die at a higher rate than in some combat posts) to bring sushi-grade tuna to university-town foodies. No, presumably these jobs would remain staffed as they currently are (with an appalling lack of gender equity), even after the ideological reform has been accomplished. But, crucially, these ruffians would no longer make dick jokes among themselves as they warm their frost-stiffened fingers over a barrel fire. The professors of gender studies find this kind of “homosociality” worrying, for it is in just such scenes of male solidarity and humor, outside institutional surveillance, that “male privilege” is said to incubate. The sun-scorched roofers laying molten tar on the flat roof of a shopping mall in Louisiana in July would no longer abuse their high position to glance down the blouses of shoppers walking across the parking lot on their way into the cool air of Nordstrom. The roofers would be made to understand: that’s violence.

Sex Narcs

In 2020, to be male is to live under a moral stain. It has been decided that male sexuality is illegitimate. Of course, it has always posed a problem for society, as something that needs to be domesticated—made generative rather than destructive—because it presents hazards as well as indispensable energies. It provides both obstacles to the civilizing project of moral formation, and the basic material for that project, with all its humanizing nuances. Currently we view it through the simplifying lens of the criminal code—concepts such as sexual assault and sexual harassment are made to stand for male sexuality altogether.

In an eye-opening law review article titled “The Sex Bureaucracy,” two Harvard law professors with impeccable feminist credentials report in great detail what they call “the bureaucratic leveraging of sexual violence and harassment policy to regulate ordinary sex.” The story told by Jacob Gersen and Jeannie Suk is focused mainly on universities.

Title IX of the 1972 Education Act was straightforward and answered perfectly well to a democratic consensus of the time: educational institutions should not discriminate based on sex. As in “you’re a woman, you can’t attend this school.” The object of its control was institutions. But the powers said to emanate from Title IX not only expanded, they became different in kind. Its object of control is now students: universities, as franchisees of the federal government, must manage student sexual relations with one another. This transformation has taken place outside the legislative process, where it would be subject to democratic pressures (and hence common opinion), and has instead been internal to the federal rule-making apparatus.

Universities tend to interpret rules according to the timeless institutional principle of maximum ass-covering, which lines up nicely with the prime directive of any bureaucracy: it must expand, like a shark that must keep moving or die. Thus the legal obligation universities have to promptly alert their communities of a serious and ongoing threat (for example, when there is an active shooter on campus) has been interpreted to require an e-mail blast to all students and faculty when there has been a reported incident of “unwanted touching and grinding.” As Gersen and Suk say,

this sort of live incident-by-incident e-mail blast is not just reporting. It is constructing the environment in which students and employees live and work. Such messages communicate that the university is a sexually dangerous place. They remind us that the educational environment contains a constant exposure to underlying sexual risk, and that the bureaucracy is monitoring.

To spend formative years in such an institution is to learn that relations between men and women are at bottom conflictual. Who is served by this? The bureaucracy itself, for it feeds on conflict.

Under the Clery Act that governs universities, lack of consent triggers the reporting requirements for an act of sexual misconduct. But what consent consists of is not defined. As Gersen and Suk detail, some schools define consent in such a way as to render most sexual interactions (of the kind that people actually have) “nonconsensual.” Incidents of misbehavior need to be multiplied for the continued health of the institution; they become the occasion for fresh initiatives, mandatory workshops, and further bloating of the administration. This is done not only by defining sexual assault downward, but by expanding the dragnet of surveillance. Under an Obama White House initiative called “It’s On Us,” incoming students are taught to keep an eye out for the precursors of sexual misconduct, and to intervene if they see something amiss. (Did he fetch her a second beer, without her asking him to?)

Presumably most students have little interest in becoming freelance sex narcs. But a few will take to it with zeal. Increasingly, to get into a good university requires that middle-class students craft their teenaged selves with a single-minded focus on being appealing to college admissions officers, with a demonstrable portfolio of achievements and dispositions. It may come quite naturally to internalize the demand for sexual vigilance coming from the staff of the Office of the Dean for Student Life and its sprawling apparatus (Harvard, for example, has over 50 Title IX administrators on staff).

A schematic description of inherently messy experience saves us the difficult, humanizing effort of interpretation. Taking up the flattened understanding offered by the bureaucrats can be a relief. On campus, we see a reduction of the entire miasma of teenage sexual incompetence—with its misplaced hopes and callow cruelties—to the legal concept of consent. Sufficiently catechized in consent-talk, a young woman may be left with no other vocabulary for articulating her unhappiness and confusion over a sexual encounter. Accepting the simplified schema, it then becomes possible to speak sincerely of a campus “rape culture.” This adds some righteous heat to her unhappiness and redeems the bad sexual experience as a political awakening. Thus does “youthful idealism” get harnessed to the expansion of police powers. Behavior that once would have gotten a young man condemned as a cad—he “took advantage” of a girl—is called sexual assault. A term of moral disapprobation is replaced with a term borrowed from the felony criminal code, but applied in the extra-legal setting of campus tribunals—which are generally secret and have none of the procedural protections of a law court.

Supply and Demand

The supreme court’s Lawrence v. Texas decision in 2003 cleared away the last impediments to sexual license between consenting adults. In his dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia lamented that this decision spelled the end of morals legislation altogether. Can his dissent be safely dismissed as prudery? Any sexual libertine today would have to join Scalia, for the end of morals legislation coincided with a ramping up of morals administration, which has turned out to be far more ambitious in its reach, immune as it is to constitutional limits and democratic pressures.

What is all of this doing to people’s sexual consciousness? Contrary to overheated reports about hookup culture, it appears to be making young men and women wary of one another. Writing in the Atlantic, Kate Julian gathers data on a “sex recession” that has set in among younger Americans. One statistic: “People now in their early 20s are two and a half times as likely to be abstinent as Gen Xers were at that age.” The reasons for this are hard to know, and doubtless complex. But a conflictual view of sex is surely part of the picture. We get a glimpse of the changes afoot from a November 2017 Economist/YouGov poll which found that 17% of Americans ages 18 to 29 now believe that a man inviting a woman out for a drink “always” or “usually” constitutes sexual harassment.

“No one approaches anyone in public anymore,” said one of Julian’s informants. It’s safer to find a mate online, where the ambiguities have been dispelled by the mere fact of finding one another on the dating app. No boldness is required, no crossing that line, as one must do when romantic initiative is exercised within the routines of daily life. Instead it is hived off into a separate realm of screens where one simply follows a script that is tacit in the dating app itself—another kind of bureaucratic supervision.

Some of the young women interviewed by Julian feel bereft of male attention, and can only fantasize what it might be like to have a serendipitous encounter in which a man chats you up in a bookstore, for example, after noticing your good taste in books. But they also dismiss this fantasy as anachronistic, or somehow wrong. It doesn’t make sense to want to be flirted with, given the paranoia they have been schooled in.A young woman’s desire for intimacy may have to become fairly acute before it can puncture the protective layer of hostile political interpretation laid upon her by institutions. One way to soften that membrane is with alcohol, which perhaps helps to account for the role it plays in college.

Why do so many college women flock to frat parties, even now? For reasons that vary, presumably. It may be that some simply don’t believe the institutional rape talk. Or perhaps they find it just plausible enough to be a little bit exciting. (A data scientist examining the vast trove of searches on the porn site PornHub found that, among viewers, women are more than twice as likely as men to search for violent and nonconsensual sex acts.)It seems more likely the excitement comes from escaping the heavy administrative hand that lays upon them. Presumably these are the rebellious ones, less inclined to adhere to the scripts repeated by the grownups.

Most people are not rebellious, and one can speculate further whether the investment of our institutions in exaggerating sexual conflict might help to account for the rising cultural prestige of homosexuality. For a man, to be gay is the only way to be beyond reproach. For a woman, to be gay is the only way to be safe. Conversely, to be a straight male, especially one who identifies as feminist, requires constant vigilance against the corrupting influence of his own most basic inclinations.

Michel Foucault, in his essay “The Battle for Chastity,” wrote of sexual renunciation in early Christianity, documenting a shift that occurred from simple prohibitions to complex techniques of self-analysis. “With Tertullian [circa A.D. 200] the state of virginity implied the external and internal posture of one who has…adopted the rules governing appearance, behavior and general conduct that this renunciation involves.” A couple of centuries later, a new arena of asceticism had opened up. “This has nothing to do with a code of permitted or forbidden actions, but is a whole technique for analyzing and diagnosing thought, its origins, its qualities, its dangers, its potential for temptation and all the dark forces that can lurk behind the mask it may assume.” What is required is “a suspiciousness directed every moment against one’s thought, an endless self-questioning to flush out any secret fornication lurking in the inmost recesses of the mind.”

This passage could serve well to describe the burden of self-suspicion borne by the male feminist, stewing over his privilege. It is vigilance not merely against acts but against impure thoughts and gazes. The antique term “fornication” is apt in this setting, if we take it to mean illegitimate male desire. If a man’s desire is directed toward a woman, its legitimacy is ipso facto a matter for scrutiny.

The class of young men who go to elite colleges feel this long before they arrive, and it surely plays a role in the project of adolescent self-fashioning. Who hasn’t noticed that stereotypically gay-sounding speech and other affectations have gone mainstream, adopted by young males who aren’t in fact homosexual? This would seem to be a case of “performative disaffiliations with heterosexuality,” in the words of writer Indiana Seresin. I take it to be the waving of a cultural white flag with respect to one’s own masculinity, by which one declares oneself a non-threat and seeks approval for this gesture.

Wearing the Pants

Jean-Jacques Rousseau said that if you want men to be virtuous, teach women what virtue is. He meant that in exercising their prerogative to be sexually choosy, women exert a formative influence on men, who will adapt themselves to be pleasing to women. There is now a simmering discontent that some women feel with the type of mate they have been taught to prefer, and through that preferring brought into existence.

Advertising offers a useful window onto the state of culture. A woman is behind the wheel of a Kia SUV, her husband in the passenger seat, the kids in back. They have arrived at a crowded event and are looking for parking. The husband, looking backward, says, “We should take that spot.” The woman says nothing and keeps driving. A strong and silent type, she is used to keeping her own counsel in the face of such capitulation. But we see the play of contempt on her face and hear a voiceover that is her sarcastic internal monologue: “Yeah, or we could drive back home, park, and walk here.” To the alarm of her husband she proceeds forward and off the pavement. The SUV climbs a steep berm of grass and stops. She has made her own damn parking spot. “Somebody in this family’s got to wear the pants,” she says to herself.

In another Kia ad, a family is leaving a football game in which their young son has played. The husband, beaming with supportiveness, says to the son, “You played a great game today, buddy!” Once again, we hear the woman’s silent thoughts from the driver’s seat: “Not really. He’s just…not good.”

In these ads, it falls to the woman to bring certain energies that we still associate with men in our backsliding moments: the power of decisive action and risk-taking, an instinctive contempt for weakness, and clear-sighted disregard for feel-good fluff, in the name of reality. Good for her. As she rightly says, somebody’s got to wear the pants.

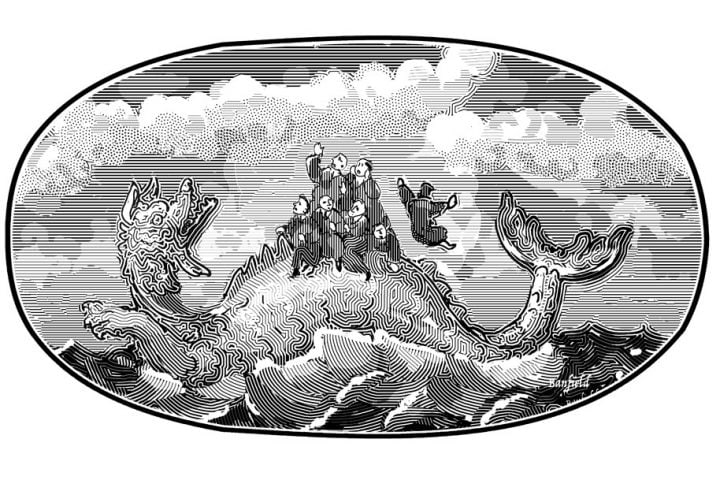

Plutarch relates that when the army of a certain city was routed, retreating to safety within the city walls, the mothers of the city closed the gate against them, climbed up on the wall, lifted their skirts, and said, “what are you doing—trying to climb back in here?” The army went back out to fight, and prevailed.

Once, in the staging area where contestants were preparing for a dangerous motorcycle race, I heard a woman who looked remarkably like Roseanne Barr bark at a lanky young man with a hesitant look on his face whom I took to be her son: “Quit being a f–king vagina!” It was perhaps a saltier version of the sentiment that Plutarch records among the Spartan women, who would tell their sons going off to battle, “return with your shield, or on it.” The lower middle class is where patriarchy is said to remain the most unreconstructed. Yet such patriarchy, if that is what it is, appears quite compatible with cock-sure women who seem to have no problem controlling their men—if necessary, by berating them to “man up.”

The bourgeois wife depicted in the Kia ad probably went to college and feels she doesn’t have permission to express such backward, “gendered” demands. Instead she festers in silent contempt—such is the price of having a respectable family that embraces ideological reform.