Books Reviewed

In August 1944, with the Red Army fast approaching, Germany began the final liquidation of Poland’s Lodz ghetto. By the time the Soviets arrived, only 800 of the 230,000 Jews living in Lodz in 1939 remained. Some were murdered in the ghetto; most were deported, to be killed at Auschwitz or Chelmno. Rywka Lipszyc was among those deported to Auschwitz, along with her sister, Cipka, and three cousins. Her journey from childhood to death camp is sadly similar to that of many other European Jewish children during the Holocaust. Unlike almost all of those taken to Auschwitz, however, the 14-year-old Rywka managed to leave behind a testimony of these horrors—a fascinating, heartrending narrative, lost for almost 70 years, now published as Rywka’s Diary.

Born September 15, 1929, and raised in a deeply religious home, Rywka was the eldest of Yankel and Miriam Sarah Lipszyc’s four children. Both of her parents died in the ghetto—her father after a beating in 1941, her mother in 1942. She was “adopted” with her siblings and cared for by uncles and aunts, but after the szpera (“curfew”) in September 1942—when 15,000 Jews under the age of 10 and over 65 were deported—only Rywka and Cipka remained. They were taken in by their 20-year-old cousin, Estusia, and survived both the ghetto’s liquidation and the journey to Auschwitz.

Rywka’s diary was found in the ruins of the ovens of Auschwitz-Birkenau by Zinaida Berezovskaya, a physician serving with the liberating Red Army. The appearance of a slightly singed book that somehow survived the crematorium apparently moved Berezovskaya, who took the diary home with her to Siberia. It stayed there until she died, when her effects were sent to her son in Moscow. He paid the book no notice, and when he died his belongings went to his wife, whose daughter, Anastasia Berezovskaya—an emigrant to San Francisco—recognized what a treasure they held.

Anastasia found experts in the Bay Area who made the diary accessible to a wide readership. It was published in 2014 by the San Francisco Jewish Family and Children’s Service Holocaust Center under the expert and caring shepherding of Anita Friedman; HarperCollins’s new edition joins to the diary a series of thoughtful essays, adding depth and nuance to our appreciation of a misleadingly simple text. Alexandra Zapruder, an expert on the Holocaust, provides an introduction and thoughtful reflections on the gradually emerging identity of a young woman under circumstances extraordinary and horrifying. Historian Fred Rosenbaum’s essay on the Lodz ghetto describes the context in which Rywka wrote, while Hadassa Halamish, the daughter of one of Rywka’s two surviving cousins, recounts her mother’s and aunt’s recollections of the time they spent with Rywka.

* * *

It is impossible for such a diary not to invite comparisons to the diary of Anne Frank, a classic of Holocaust literature. Rywka Lipszyc and Anne Frank were very different young women from very different sorts of Jewish homes. Anne’s diary is the more self-aware, reflecting both the horror of her life under Nazi occupation and, at the same time, her budding sexuality. Rywka, in contrast, seems determined to ensure that her nascent womanhood nowhere informs her writing.

Yet Rywka’s Diary reveals other, no less instructive struggles. Rywka began writing the only surviving volume of her diary shortly after her 14th birthday. Comprising 112 handwritten pages, it covers October 1943 to April 1944, when she suddenly stopped writing. Aside from the anguish and loneliness, the fear and the hunger, there slowly emerges—mostly between the lines—a shifting attitude to the idea of the creation of a Jewish State.

Antebellum Eastern Europe’s religious Jews were ambivalent about, if not unabashedly opposed to, Zionism. After centuries of dispersion they had come to believe that they had a religious duty to remain in exile until God redeemed them. To them, Zionism—which sought to place the fate of the Jews in human hands—was a violation of the essence of Judaism’s submissiveness. That most Zionist leaders were rabidly anti-religious confirmed this sense. The religious railed against the Zionists, and often banished from their communities anyone who would dare to breach the separation.

* * *

This antipathy to Zionism is evident in an early entry in the diary (January 20, 1944), a rather naïve paragraph in which Rywka writes, “That’s why I’m not surprised anymore that the Zionists put Palestine in the first place, and the Torah in the second place. Others don’t care about the Torah at all…. Poor things!” But the Holocaust gradually shifted religious Jews’ attitudes, a change apparent in the diary. Just two weeks after the January 20 entry, Rywka imagines with pleasure the possibility of Jews returning to their homeland: “Bala [her teacher] asked us to write how we imagined our arrival in Palestine…. There are different girls in the class and she wants to know…whether they are Zionists…. [H]ow much longing I have for this land!”

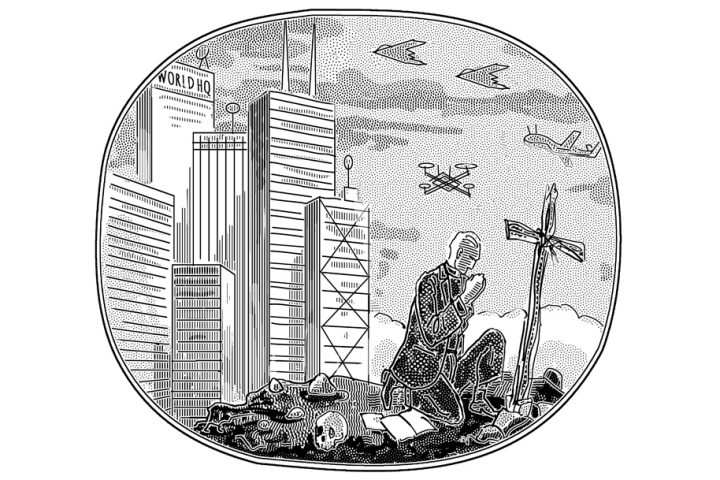

In an era in which talk about the State of Israel focuses heavily on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Rywka’s Diary is a reminder that, at its core, Zionism was a political movement designed to save the Jewish people. As Rywka’s situation becomes more desperate, the image of the Jewish people situated in their ancestral homeland—a notion she had once seen as heretical—becomes more appealing.

To drive home the point that, despite its complications, the Jewish State has given the Jewish people a new lease on life, a photograph of Rywka’s two cousins—the only family members to survive the Holocaust—follows several pages later. Unlike Rywka and her sister, her cousins Mina and Esther survived the war, liberated by the Red Army and sent to Sweden for medical care. They eventually made their way to Israel, married, and raised families. By the time of the photo they are elderly women, surrounded by their families—some 75 people—who are to all appearances observant Jews. The point can be lost on few. Eastern Europe’s anti-Zionist Jewish leaders were wrong: their faith did not save them, and what remains of their communities has thrived, by and large, in the state they refused to help create before the war.

* * *

Towards the end of the volume Rywka’s cousin Esther writes, “With the finding of the journal…it was revealed to us that she remained alive for a number of months after we left. In a document from September 1945 that was found, she wrote that she wanted to come to Eretz Yisrael [the land of Israel]. However, we still don’t know where she went.” Then, the essay concludes, “Perhaps this book, once published and publicized, will help reveal her fate.”

There can be little doubt concerning Rywka’s fate: gravely ill at the war’s end, she almost certainly died in 1945. We might be tempted to imagine that we have not much more to gain from reading yet another heartbreaking Holocaust story. But the combination of Rywka’s musings on Zionism, the breathtaking photo of her cousins’ families, and the knowledge that she, too, could have been saved had her community heeded the warnings of secular, Zionist Jews makes this volume not only a compelling window into the lives of Jews in the Lodz ghetto on the eve of extermination, but a moving reminder of the occasional dangers of theological certainty, when faith fails to take into account the horrifying dynamics of a rapidly changing world.