America has approached the war on terrorism as if from two dreamworlds. The liberal, in which an absurd understanding of cause and effect, the habit of capitulation to foreign influence, a mild and perpetual anti-Americanism, reflex allergies to military spending, and a theological aversion to self-defense all lead to policies that are hard to differentiate from surrender. And the conservative, in which everything must be all right as long as a self-declared conservative is in the White House—no matter how badly the war is run; no matter that a Republican administration in electoral fear leans left and breaks its promise to restore the military; and no matter that because the Secretary of Defense decided that he need not be able to fight two wars at once, an adequate reserve does not exist to deal with, for example, North Korea. And in between these dreamworlds of paralysis and incompetence lies the seam, in French military terminology la soudure, through which al-Qaeda, uninterested in our parochialisms, will make its next attack.

The war is waged as if accidentally, and no wonder. For domestic political reasons and to preserve its marginal relations with the Arab World, the United States has declined to identify the enemy precisely. He is so formless, opportunistic, and shadowy that apparently we cannot conceive of him accurately enough to declare war against him, although he has declared war against us. Attribute this to Karl Rove’s sensitivity to the electoral calculus in key states with heavy Arab-American voting, to a contemporary aversion to ethnic generalities, to the desire not to offend the Arab World lest it attack us even more ferociously, to the fear of speaking truth to oil, to apprehension about the taking of hostages and attacks upon embassies, and to a certain muddledness of mind that is the result both of submitting to polite and obsequious blackmail and of having been throughout the course of one’s life a stranger to rigorous thought.

Reluctance to identify the enemy makes it rather difficult to assess his weaknesses and strengths. Thus, for want of a minimum of political courage, our soldiers are dispatched to far-flung battlefields to fight an ad hoc, disorganized war, and, just as it did in the Vietnam War, Washington explains its lack of a lucid strategy by referring to the supposed incoherence of its opponent. From the beginning, America has been told that this is a new kind of war that cannot be waged with strategic clarity, that strategy and its attendant metaphysics no longer apply. And because we cannot sufficiently study the nature of an insufficiently defined enemy, our actions are mechanistic, ill-conceived, and a function of conflicting philosophies within our bureaucracies, which proceed as if their war plans were modeled on a to-do list magnetized to some suburban refrigerator.

* * *

The enemy must and can be defined. That he is the terrorist himself almost everyone agrees, but in the same way that the United States extended blame beyond the pilots who attacked Pearl Harbor, it must now reach far back into the structures of enablement for the sake of deciding who and what must be fought. And given the enormity of a war against civilians, and the attacks upon our warships, embassies, economy, capital, government, and most populous city, this determination must be liberal and free-flowing rather than cautious and constrained, both by necessity and by right. The enemy has embarked upon a particular form of warfare with the intent of shielding his center of mass from counterattack, but he must not be allowed such a baseless privilege. For as much as he is the terrorist who executes the strategy, he is the intelligence service in aid of it, the nation that harbors his training camps, the country that finances him, the press filled with adulation, the people who dance in the streets when there is a slaughter, and the regime that turns a blind eye.

Not surprisingly, militant Islam arises from and makes its base in the Arab Middle East. The first objective of the war, therefore, must be to offer every state in the area this choice: eradicate all support for terrorism within your borders or forfeit existence as a state. That individual terrorists will subsequently flee to the periphery is certain, but the first step must be to deny them their heartland and their citadels.

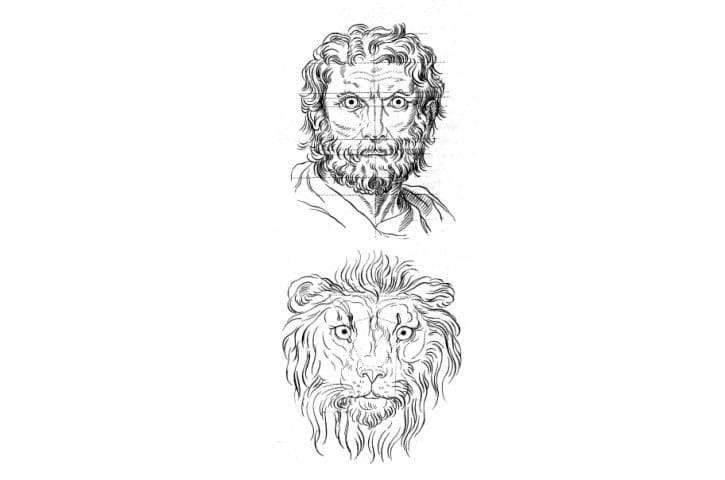

Recognizing that the enemy is militant Islam with its center the Arab Middle East, it is possible to devise a coherent strategy. The enemy’s strengths should not be underestimated. He has a historical memory far superior to that of the West, which has forgotten its thousand-year war with Islamic civilization. Islamic civilization has not forgotten, however, having been for centuries mainly on the losing side. Its memory is clear, bitter, and a spur to action. And it dovetails with a spiritual sense of time far different from that of the West, where impatience arises in seconds, for the enemy believes that a thousand years, measured against the eternity he is taught to contemplate and accept, is nothing. Closely related to his empowering sense of time are his spiritual sense of mission, which must never be underestimated, and Islam’s traditional embrace of martyrdom.

This militant devotion, consciously or otherwise, pays homage to the explosive Arab conquests, which reached almost to Paris, to the gates of Vienna, the marchlands of China, India, and far into Africa. War based on the notion of Islamic destiny is underway at this moment in the Philippines, Indonesia, Sinkiang, Kashmir, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Chechnya, Iraq, Palestine, Macedonia, Algeria, the Sudan, Sub-Saharan Africa, and throughout the world in the form of terrorism without limitation or humanitarian nuance—all in service of a conception far more coherent than the somnolent Western nations seem to comprehend. The object long expressed by bin Laden and others is to flip positions in the thousand-year war. To do this, the Arabs must rekindle what the 10th-century historian Ibn Khaldun called ‘asabiya, an ineffable combination of group solidarity, momentum, esprit de corps, and the elation of victory feeding upon victory. This, rather than any of its subsidiary political goals, is the objective of the enemy in the war in which we find ourselves at present. Despite many flickers all around the world, it is a fire far from coming alight, but as long as the West apprehends each flare as a separate case the enemy will be encouraged to drive them toward a point of ignition, and the war will never end.

The proper strategic objective for the West, therefore, is the suppression of this fire of ‘asabiya in the Arab heartland and citadels of militancy—a task of division, temporary domination, and, above all, demoralization. As unattractive as it may seem, in view of the deadly alternative it is the only choice other than to capitulate.

* * *

How might it be accomplished? as much as those who make war against the West find advantage in Arab history and Islamic tradition, they are burdened by its disadvantages. Living in a world of intense subjectivity where argument is perpetually overruled by impulse, they suffer divisions within divisions and schisms within schisms. Though all-consuming fervor may be appropriate to certain aspects of revealed religion, it makes for absolutist politics and governance. A despotic political culture in turn decreases the possibilities of strong alliances and is (often literally) murderous to initiative, whether technical, military, or otherwise. And it is of no little import that the Middle East has developed so as to be unreceptive to technology.

The natural environment of Arabia is so extreme that the idea of mastering it was out of the question, submission and adaptation being the only options, and the Middle East had neither the kind of surplus agriculture that permitted Europe to industrialize, nor the metals and wood upon which the machine culture was built. Technology was viewed not as a system of interdependent principles, but rather as finite at all stages, not an art to be practiced but a product to be bought. Magical machines arrived whole, without a hint of the network of factories, workshops, mines, and schools, and the centuries of struggle and genius it took to build them. Islam provides a successful spiritual equilibrium that the whole of Islamic society strives to protect. The West, by its very nature, stirs and changes everything in “creative destruction.” Wanting no part in this, the Middle East, to quote the economic historian Charles Issawi, “believed that the genius of Islam would permit a controlled modernization; from Europe one could borrow things without needing to borrow ideas,” which is why, perhaps, in 19th-century Egypt, students were sometimes taught a European language to master a craft, and then told to “forget” the language.

Even more potentially fatal to the Arabs than the fact that they cannot ever win a technological duel with the West is their Manichean tendency to perceive in wholly black or wholly white. In the Middle East the middle ground is hardly ever occupied, and entire populations hold volatile and extremist views. This is traceable perhaps to the austerities of the desert and nomadic life, and is one of the great and magnetic attractions of Islam—severity, certainty, and either decisive action or righteous and contented abstention. In Arab-Islamic culture, things go very strongly one way or they go very strongly the other, and, always, a compassionate haven exists for the defeated, for martyrs, as long as they have not strayed from the code of honor. In the West, success is everything, but in the Arab Middle East honor is everything, and can coexist perfectly well with failure. The Arabs have a noble history of defeat, and are acclimatized to it. Their cultural and religious structures, far less worldly than ours, readily accommodate it. Though wanting victory, they are equally magnetized by defeat, for they understand, as we used to in the West, that the defeated are the closest to God.

The West seems not to know, George W. Bush seems not to know, and Donald Rumsfeld seems not to know, that there can be but one effective strategy in the war against terrorism, and that is to shift Arab-Islamic society into the other of its two states—out of nascent ‘asabiya and into comfortable fatalism and resignation. The British have done this repeatedly, and the United States almost did it during the Gulf War. That the object of such an exercise is not to defeat the Arabs but to dissuade them from making war upon us means it is more likely to succeed now than when it was joined to religious war in the Crusades or to the imperial expansion of Europe. Now we want only to trade with the oil states even at scandalous expense, and not (assuming that “nation-building” is properly allowed to atrophy) to convert, control, or colonize. How, exactly, does one shift Arab-Islamic society into the other of its two states?

* * *

If one were to calculate a fortiori the scale of military effort involved in the 19th-century division of the Ottoman Empire and the subsequent European domination of the Middle East, one would undoubtedly assume that the Europeans deployed great armadas and large armies. More than 30 years ago, a graduate student asked the late and eminent Oxford historian Albert Hourani what numbers the Europeans did, in fact, deploy. He said he would look into it, and a week later reported that, to his astonishment, the only European military presence within the periphery of the Ottoman Empire that he could discover, from Napoleon until the latter part of the 19th century, were 1,500 British and 500 Austrian troops in 1840, and 6,000 French in 1860. Thus can minuscule expeditions conquer vast empires, Aztec, Inca, or Ottoman.

But not today, or at least that would seem to be a reasonable conclusion. For in the last century the Arabs have organized into separate and self-stabilizing states; they have raised large military establishments, so that now Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and (non-Arab) Iran have 1.5 million regulars under arms; they have bought and sometimes successfully absorbed huge inventories of modern weapons; they have fought wars of independence and revolution, civil wars, against Israel six times, and against the great powers; and from T. E. Lawrence, Mao, and Ho Chi Minh they have learned at least the rudiments of asymmetrical warfare.

Nevertheless, the fundamental relation has not been altered, and it is still possible to maneuver the Middle East into quiescence vis-a-vis the West. It is a matter mainly of proportion. The unprecedented military and economic potential of even the United States alone, thus far so imperfectly utilized, is the appropriate instrument. Adjusting military spending to the level of the peacetime years of the past half-century would raise outlays from approximately $370 billion to approximately $650 billion. If the United States had the will, it could, excessively, field 20 million men, build 200 aircraft carriers, or almost instantly turn every Arab capital into molten glass, and the Arabs know this. No matter what the advances in regional power, the position of the Arab Middle East relative to that of the United States is no less disadvantageous than was that of the Arab Middle East to the 19th-century European powers. But, given the changes listed in the previous paragraph, the signal strength necessary to convey an effective message is now far greater.

In the Gulf War, the overwhelming forces marshaled by the coalition might have sufficed as such a signal but for the fact that they were halted prematurely and withdrawn precipitously, gratuitously leaving both Saudi Arabia and Iraq an inexplicable freedom of action that probably left them stunned by their good luck.

Before the Iraq War, high officials were seriously considering an invasion force of 500 backed by air power. The numbers climbed steadily: 5,000, 10,000, 20,000, 25,000, 40,000, 50,000, 60,000, and so on, with the supposedly retrograde “heavy army” prevailing finally, and 300,000 troops in the theater. When offered vehement advice to go into Iraq with massive force and many times overkill, a brilliant and responsible senior official responded, almost with incredulity, “Why would we need the force that you recommend, when in the Gulf War we used only 10 percent of what we had?” In the Gulf War, we did not occupy a country of 23 million.

As of this writing, the army reportedly has 23 combat brigades, 18 of which are deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan, three of which are in refit, one in Kosovo, and two in Korea, leaving nine brigades, or about 45,000 men, to pick up the slack anywhere and everywhere else. Though independent echelons and the Marines increase this figure many fold, they do not have sufficient lift and logistics, and even if they did it would not be enough. This is as much the result of the Bush Administration’s failure to increase defense spending appreciably and rebuild the military before (and even after) September 11, as the lack of real shock and awe was the result of the administration’s desire to go to war according to a sort of just-in-time-inventory paradigm. Managers rather than strategists, they did not understand the essence of their task, which was not merely to win in Iraq but to stun the Arab World. Although it is possible, with just enough force, to win, it is not possible, with just enough force, to stun. The war in Iraq should have been an expedition originating in the secure base of Saudi Arabia, from the safety of which the United States could with immense, husbanded force easily reach anywhere in the region. The eastern section of the country, far from Mecca and Medina, fronting the sea, with high infrastructure and large spaces for maneuver, basing, and an air-tight defense, is ideal. Had the Saudis not offered this to us, we might have taken it, which probably would have been unnecessary, given that our expressed determination would likely have elicited an invitation. As it was, we were willing to alienate the entire world so as to thrust ourselves into a difficult situation in Iraq, but unwilling to achieve a commanding position in Saudi Arabia for fear of alienating the House of Saud. One might kindly call this, in that it is about as sensible as wearing one’s clothes backwards, “strategic hip hop.”

It was, in any case, some kind of deliberate minimalism. Sufficiency was the watchword. The secretary of defense wanted to show that his new transformational force could do the job without recourse to mass. The president wanted no more than sufficiency, because he had not advanced and had no plans to advance the military establishment beyond the levels established by his predecessor. With the magic of transformation, he would rebuild it at glacial pace and little cost lest he imperil his own and Republican fortunes by embarking on a Reagan-style restoration after an election decided by as many voters as would fit in a large Starbucks, and that he won by leaning, un-Reagan-like, to the center.

The war in Iraq was a war of sufficiency when what was needed was a war of surplus, for the proper objective should have been not merely to drive to Baghdad but to engage and impress the imagination of the Arab and Islamic worlds on the scale of the thousand-year war that is to them, if not to us, still ongoing. Had the United States delivered a coup de main soon after September 11 and, on an appropriate scale, had the president asked Congress on the 12th for a declaration of war and all he needed to wage war, and had this country risen to the occasion as it has done so often, the war on terrorism would now be largely over.

But the country did not rise to the occasion, and our enemies know that we fought them on the cheap. They know that we did not, would not, and will not tolerate the disruption of our normal way of life. They know that they did not seize our full attention. They know that we have hardly stirred. And as long as they have these things to know, they will neither stand down nor shrink back, and, for us, the sorrows that will come will be greater than the sorrows that have been.