Of the questions that arose last July when the Supreme Court abolished affirmative action for college admissions, the one that most riled the program’s defenders was: why now? In her truculent and powerful dissent in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, Justice Sonia Sotomayor described the decision as having been handed down “without any new factual or legal justification.”

She seemed to have a point. Chief Justice John Roberts’s opinion gave three substantive reasons for finding that the systems of racial preference at Harvard and the University of North Carolina were constitutionally out of bounds: the plans were not just a boost to blacks and Hispanics but an unfair bias against whites and Asians; they relied on racial stereotypes; and they were too vague to meet the court’s standards of scrutiny. These problems have been inherent in the American system of racial preferences from the moment President Lyndon Johnson devised it for workplaces in a 1965 executive order; the Court’s objections would have applied just as well in the 1978 case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, which would greenlight university affirmative action for almost two generations.

And yet Sotomayor is wrong to say nothing has changed. A lot has changed. In Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), the Court okayed racial preferences at the University of Michigan’s law school but warned that affirmative action programs were permissible only as temporary expedients, since they were at odds with the 14th Amendment principle of equal protection. It was expected they would end within 25 years.

The passage of time, then, would have sufficed to overturn affirmative action. But since Grutter, the program’s internal contradictions and constitutional outrages have worsened.

Systemic Radicalism

For one thing, immigration has altered the demographics of the United States. Six decades after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the country has gone from having a minuscule East Asian population, almost invisible outside a few Chinatowns and tightly circumscribed Pacific areas, to being 6% “Asian.” Members of that official census designation, arbitrary though it may be, have turned out to be extraordinarily fit for higher education. Their successes have thrown into disarray the plans of white bureaucrats and black activists to divvy up university spaces according to Great Society notions of fairness. In the early days of affirmative action, colleges promised to carve out for aspiring blacks a few spots that the overwhelming white majority would hardly miss. But the ambitions of college administrators have grown. Today, whites are under-represented on the nation’s campuses, making up as few as 42% of undergraduates. And that in a steeply declining college population: enrollment is down 15% since 2010, with most of the decline antedating the COVID lockdowns.

Pressure has grown on the semi-meritocratic, semi-race-based system. Opening up spots for blacks and Hispanics has come to require a more active kind of racial discrimination. Bias against Asian applicants—the focus of the two freshly decided cases brought by Students for Fair Admissions—is particularly glaring. In the Harvard data reviewed by the Court, a black applicant in the top four academic deciles was between four and ten times as likely to be admitted as an Asian with a similar record. A black student who ranked between the 30th and 40th percentile of applicants was more likely to be admitted to Harvard than an Asian who ranked between the 90th and 100th. Given the recent immigrant origins of most Asian students, emotional allusions to 19th-century slavery and 20th-century segregation have not sufficed to bully the public out of studying the unfairness calmly.

The court record describes a focus on race verging on obsession. At Harvard, a “lop list” was likely used to bring incoming classes within desired racial parameters. At UNC, the preoccupation is evident in admissions officers’ text messages:

perfect 2400 SAT All 5 on AP one B in 11th [grade]

Brown?!

Heck no. Asian.

Of course. Still impressive.

Or:

If its brown and above a 1300 put them in for merit/Excel [a scholarship]

This is a far cry from the mere “tip” that affirmative action was designed to offer in a handful of cases.

Another new problem is visible in Sotomayor’s dissent itself. Affirmative action’s defenders have been radicalized. For them, affirmative action is no longer a means of opening up America’s social order but a means of overthrowing it. “Equality is an ongoing project in a society where racial inequality persists,” writes Sotomayor. The project is open-ended and its moral authority absolute. When people warned back in the Carter and Reagan administrations that countenancing even small doses of federal government race bias risked corroding the wider political culture, they were thinking of something like our diversity/equity/inclusion agenda.

Compared with the declamations of Sotomayor, Justice Roberts’s decision feels like something out of another era. An admirer would call it juridical. A detractor would call it oblivious. Masticating certain Republican grievances from the 1990s, the decision lays down the mildest version of the case against affirmative action—a set of reforms, really. Compared to, say, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which read like a ukase, the decision in SFFA v. Harvard reads more like an op-ed.

“The Supreme Court,” wrote New York Times columnist and lawyer David French in the days after the ruling, “is in many ways a throwback to the status quo before Donald Trump descended his escalator.” He is right. The decision shows no cynicism about progressive race policies or about the motives of those who administer race-focused programs. The majority Justices appear to understand affirmative action as an isolated and perhaps unwitting violation of the Constitution in the service of a noble ideal. They do not think of affirmative action as a fundamental component in an alternative constitutional power structure, an institution that has escaped popular efforts to restrain it in the past (see William Voegeli’s “They Never Did Mend It” on page 14) and will be defended with all the tenacity and ingenuity at the disposal of those who administer it. The Court has not really grasped the nettle.

The decision in Students for Fair Admissions doesn’t lay down any principle. It enunciates no Thou Shalt Not. It doesn’t call for anything to be done with “all deliberate speed,” nor does it overrule Bakke or Grutter, nor does it question the “diversity” principle they enshrined. True, certain universities—including the University of Virginia and the University of North Carolina itself—announced changes in their application processes in the wake of the SFFA decision. But the most important question to ask of that decision may be whether it has actually abolished affirmative action at all.

Diversity: A Conservative Idea

The confusing structure of the law concerning affirmative action comes from the 1978 Bakke case. Allan Bakke, a 33-year-old Marine veteran of Vietnam, applied to medical school at the University of California, Davis, and was rejected, even though his scores on the four sections of the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) were in the 96th, 94th, 97th, and 72nd percentiles. Davis reserved 16 admissions spots for a “minority group” of blacks, Asians, American Indians, and (as they were then called) Chicanos. The median scores of that year’s minority admittees, by MCAT section, were in the 34th, 30th, 37th, and 18th percentiles. Was Bakke’s exclusion racist, as he claimed? Or was it, in light of America’s racist past, a justifiable and even civic-minded act of reparation?

It was, in retrospect, a pivotal constitutional moment. The Court was charged with arbitrating between, on the one hand, certain novel constitutional principles introduced by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and, on the other, the Constitution itself.

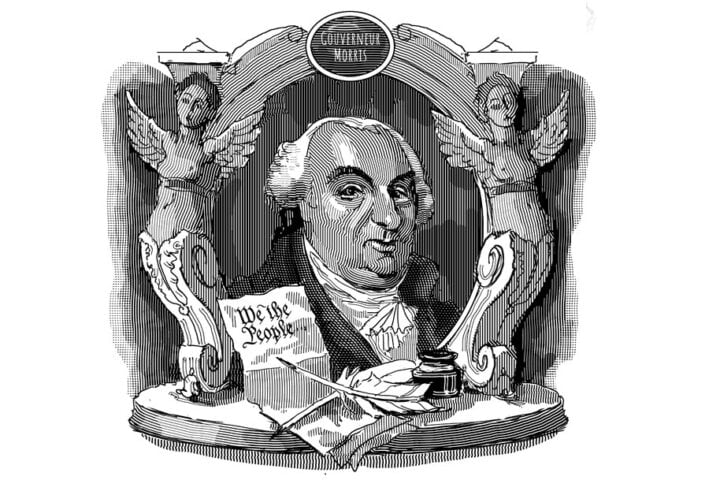

The Court deadlocked, producing six different opinions. Roughly, four Justices held that Bakke should be admitted to med school because civil rights required that college admissions be colorblind. Four held that Bakke could be rejected because civil rights permitted “reverse” racism to rectify historical imbalances and spread opportunity. It was left to Justice Lewis Powell to cast the deciding vote. He agreed with both sides. He approved affirmative action, but not the logic of reparations by which it had been justified since the Johnson Administration, and not the social engineering that was its whole point. Instead, following an amicus curiae brief in which Harvard had described its own admissions system, he defended programs like Davis’s on the grounds that they served the university’s interest in “obtaining the educational benefits that flow from an ethnically diverse student body.”

It was more a pretext than a rationale. Harvard had always been in the business of getting the best student body it could, by its own lights. It had not required the civil rights revolution to hit upon that idea. In establishing its affirmative action program Harvard was merely updating its priorities for the 1970s, recognizing that these included not just forming scholars but also transforming a racially divided society. It may have been a laudable goal. At the time it was a legal one. But the historic consequences of this successful effort to dress up political activism as academic freedom have been more extensive than anticipated. Powell’s brainstorm became, first, the “controlling opinion” for adjudicating affirmative action, and then, with Grutter, Court doctrine. More than that, it brought forth “diversity,” as that term is now understood. Today, the diversity motive vies with the profit motive as the mainspring of American economic life.

That outcome was surely far from Powell’s mind. A corporate lawyer for Virginia’s tobacco companies with an expertise in mergers and acquisitions, he had written an infamous memorandum to a colleague at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in the weeks before his nomination to the high court in 1971. Powell suggested ways that corporations could collude to fund attacks on the consumer activist Ralph Nader, the Yale law professor Charles Reich, and various other “Communists, New Leftists and other revolutionaries who would destroy the entire system.” When the columnist Jack Anderson reported on the memo a year later, Powell acquired a reputation as the most right-wing member of the Court.

Powell may well have thought his “diversity” idea was striking a blow for conservatism. Barely a decade after the Civil Rights Act, the country was living in an interregnum. Civil rights were meant to vindicate the claims of the 14th Amendment—by giving a “substantive” power to equal protection of the laws. But it did so by narrowing the scope of the First Amendment—by spelling out that the right of freedom of assembly would no longer be understood as guaranteeing freedom of association. This patch of constitutional real estate, ownership of which was disputed by the 14th Amendment and the 1st, was where Powell would pitch diversity’s mansion.

One can speculate about what was going through his mind. There were newfangled laws on the books permitting the federal government to investigate conduct that most Americans understood as personal or proprietary. Often the people uneasy about such laws were modestly situated and disinclined to fight racism: Did an old landlady really have to rent her spare bedroom to all comers? Did an Italian restaurant owner have to hire non-Italian waiters? Probably not.

But didn’t the corporate honchos who had been Powell’s clients and friends deserve similar indulgence? Many of them had different opinions than the landlady and the restaurateur. Harvard’s overseers and U.C. Davis’s admissions officers wanted not to ignore civil rights but to go the extra mile for them. Universities knew best how to assemble a community of scholars, free from the nit-picking of federal regulators. Davis, like Harvard, was asking for space. Powell was inclined to give it to them, even if it meant importing an idea of executive prerogative from pre-civil rights days.

In the language of corporate law, diversity was a “safe harbor”—a concrete way to obey laws that are too vague or idealistic to make sense of. Affirmative action itself was originally a safe harbor, as laid out in section 718 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. By establishing an affirmative action program along lines encouraged by the government, businesses could protect themselves from losing their government contracts in the cyclone of discrimination-based enforcement the law unleashed.

To non-corporate lawyers, though, the “diversity” described in Harvard’s amicus brief and Powell’s opinion was illogical, even irrational. It was a way of using the law to favor black people on account of what their forebears had been through—but this goal was now illegal to avow. It could be used only as a plus, never as a minus—but surely if one person was getting admitted to college because of his race, another was being excluded. Finally, this picture of statistical “ties” getting broken by the tiny “tip” of race described a situation that probably came up five times a year nationwide—but it was being used to justify vast programs at every university in the country. Yes, every university in the country—leave aside one or two that refused to accept any federal funds.

One thing was strange above all. Affirmative action was meant to be a liberty, something a university is allowed to do—but colleges everywhere treated it as something they were required to do. The expression that Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson uses in her dissenting opinion in Students for Fair Admissions is striking: taking race into account in affirmative action programs, she says, is something that the law “permits, but does not require.” But this is false. If affirmative action is not a de facto requirement, then why has the Supreme Court spent 45 years agonizing over whether and how to eliminate it?

Civil rights laws do not work by banning this or that. They work by incentivizing certain acts and then confronting citizens with the investigative power of the federal government and the awesome suing power that the Civil Rights Act gives to government, activist foundations, and private parties. Once the concept of racial diversity is defined in a Supreme Court decision as something that anti-racist colleges want, it comes to seem racist not to want it. No one is requiring you to do anything. But no university board member who has his institution’s endowment at stake wants to be brought into a courtroom and told: “You had the freedom to act the right way concerning race—why didn’t you avail yourself of it?” Bad things might happen to your institution should your student body wind up less than 12% black.

The problem with affirmative action has not just been in this or that way of interpreting diversity, nor in this or that tradition of Supreme Court scrutiny. The problem has always been that it is armed with the terrible swift sword of civil rights law, which works to transform every area of American law into anti-discrimination law. It was thus that, in 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act, meant to discourage immigration from Mexico by punishing employers who hired illegals, was hedged with language stressing the illegality of discriminating on grounds of national origin—and thereby wound up encouraging immigration. And it was thus that, after the riots of 2020, every single major corporation in the U.S. came to have a Diversity-Equity-Inclusion apparatus. Civil rights arrived promising to make race less important to our national life but has wound up racializing everything it touches.

Lewis Powell was trying to find a compromise between the best pre-civil rights traditions of freedom of association and the best post-civil rights traditions of racial inclusion…but the intervening decades have shown that only the latter has the power of law behind it. Civil rights have kept expanding their remit, to the point where, in the Students for Fair Admissions cases, almost any excuse for racial preferences seemed to suffice. Both Harvard and UNC defended their affirmative-action programs as a way of helping students “adapt to an increasingly pluralistic society.” Justice Sotomayor defends affirmative action on the grounds that it “drives innovation in an increasingly global science and technology industry.”

Diversity and Strength

The recent decision promises limits on the most race-conscious parts of affirmative action. But the program has by now had more than half a century to remake the country in its own image. Many of its unfairnesses have become invisible to the culture, and thus inaccessible to the Court. Sonia Sotomayor, speaking for the status quo, believes not only that affirmative action is an efficient tool in the global marketplace, but also that diversity “is now a fundamental American value.”

Clarence Thomas, it is true, has a different vision. For him, diversity may have been the subject of a number of decrees, but that does not necessarily give it a place in the hearts of Americans. Two generations after Bakke proposed the educational benefits of diversity, Thomas marvels that “with nearly 50 years to develop their arguments, neither Harvard nor UNC—two of the foremost research institutions in the world—nor any of their amici can explain that critical link.”

Maybe diversity is a strength in some circumstances, but Thomas has never seemed to care whether it is or not. In his 2013 concurring opinion in Fisher v. University of Texas, he noted that segregation was defended, when it was defended, on the grounds of efficiency. In the transcript of a Virginia case that was bundled into Brown v. Board of Education we read: “What does the Negro profit if he procures an immediate detailed decree from this Court now and then impairs or mars or destroys the public school system in Prince Edward County?” If such arguments were unconvincing then, Thomas believes, they should be unconvincing now. “Just as the alleged educational benefits of segregation were insufficient to justify racial discrimination,” wrote Thomas, “the alleged educational benefits of diversity cannot justify racial discrimination today.”

Bakke’s introduction of “diversity,” it is now evident, wrought a change in our understanding of civil rights—one that the newest Supreme Court decision has been insufficient to undo. The attitude that prevailed before Bakke was a conservative one. It was rooted in a truth about desegregation that has become a taboo: Namely, that it is difficult. Racial integration is not the only good the American polity seeks. Freedom is often at odds with inclusion, and academic excellence is often at odds with diversity. Pursuing integration too dogmatically can cause a lot of collateral constitutional damage. That, perhaps, is why Thomas urges “humility” in using race to “accomplish positive social goals.” Wisdom lies in unsentimentally facing the failures of racial integration where they arise, and granting leeway where we must. Thomas points to the proficiency of historically black (and still majority-black) colleges in producing scientists—including 50% of the country’s black doctors and 40% of its black engineers. This conception of civil rights, which dominated discussions of affirmative action when Bakke was decided 45 years ago, has gone out the window. Thomas and perhaps Samuel Alito are the last Justices to espouse it. It belongs to the last century.

It has been replaced with a new, 21st-century conception. Oddly, as Bakke’s shortcomings have grown more evident, its principles have hardened into dogma. This is almost as true for the Republican-appointed conservatives on the Court as for the Democrat-appointed progressives. No government interest—not even the First Amendment—can compete with the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Fixing Bakke involves perfecting the civil rights regime by ironing out its contradictions.

The striking thing about the two Students for Fair Admissions suits is what a very liberal, even utopian, project they serve. In a recent New York Times interview, Edward Blum, the founder of SFFA, described his aspiration to “remove the concept of race from America’s laws,” insisting that this is a project in keeping with his very liberal upbringing. Blum is not a libertarian, fighting to leave colleges to their own devices. He is keen to replicate the post-Bakke acceptance rates of blacks and Hispanics at Harvard and other top schools, and is willing to go to great lengths to do so. His filings provided a plan that would work by eliminating preferences for children of alumni and faculty (but not athletes) and increasing outreach to poor and single-parent families. Harvard argues, plausibly, that such a plan would result in an academically less distinguished student body.

Blum doesn’t believe admissions preferences for children of alumni violate the Civil Rights Act, but otherwise his zeal on the issue matches that of Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson. Neil Gorsuch vied with Sotomayor in fustian, complaining in his concurrence that Harvard’s “preferences for the children of donors, alumni, and faculty are no help to applicants who cannot boast of their parents’ good fortune or trips to the alumni tent all their lives. While race-neutral on their face, too, these preferences undoubtedly benefit white and wealthy applicants the most.”

Gorsuch is a bellwether, seemingly deaf to the context of civil rights law that existed before the age of equity. Like Roberts (who says that “eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it”), he is given to maximalist pronouncements about civil rights. “Under Title VI,” writes Gorsuch, “it is always unlawful to discriminate among persons even in part because of race, color or national origin.”

This attitude, though too dogmatic to call conservative, has produced a remarkable forensic victory for the Court’s conservative bloc: by turning non-discrimination into a categorical imperative, by battering the Left with a doctrine of absolute colorblindness, the majority has been able to flush out the defenders of affirmative action, to show that they do not really believe in non-discrimination. It is a remarkable forensic achievement. Indeed, both Sonya Sotomayor’s and Ketanji Brown Jackson’s dissents bluntly advocate race-conscious administration, though Sotomayor prefers the expression “using race in a holistic way.”

Sotomayor’s 69-page dissent is an impressive, forceful document that drives right to the heart of the disagreement between majority and minority. For long stretches it provides an originalist counter-reading of the 14th Amendment that matches Thomas’s in erudition and differs diametrically in philosophical outlook. She takes note of legislation in which the same Congress that drafted the 14th Amendment drew explicit distinctions based on race (as opposed to former enslavement). She writes:

The Fourteenth Amendment was intended to undo the effects of a world where laws systematically subordinated Black people and created a racial caste system. Brown and its progeny recognized the need to take affirmative, race-conscious steps to eliminate that system.

There are two ways to “eliminate” a system. You can cautiously dismantle it, trusting that the harms it did will fade over time. That is more or less the conservative position on civil rights, and it is what Americans thought they were getting when they backed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The second way to eliminate a system is to counteract it, running its machinery in reverse for a while in the hope of getting results faster, and trusting that you will know when to stop. That is more or less the progressive position on civil rights, and it is the one that has dominated American life since Lyndon Johnson introduced affirmative action by executive order in 1965.

Affirmative action for a long time degraded academic life, muddled constitutional thinking, and poisoned partisan politics. Those who managed educational institutions came to see diversity as more important than education itself—witness the State of California’s elimination of standardized testing requirements in the wake of the 2020 race riots. The decision to eliminate affirmative action in Students for Fair Admissions is the right one, but it is late—perhaps too late. The moment has something Gorbachevian about it. Sonia Sotomayor insists that affirmative action has become part of the American system. We may shortly see whether it can be removed without taking the system down with it.