Books Reviewed

Christopher Clark is our outstanding historian of the Great War. His 2012 account of its beginnings, The Sleepwalkers, stunned the world and set a new standard in a field that most thought exhausted. Clark was the first Western historian to enter the Russian diplomatic archives. With them he showed that Russia mobilized first and made war inevitable at a moment when Berlin still expected a localized rather than a European war. He proved that Barbara Tuchman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the war’s beginning in The Guns of August (1962) transposed the date of Russian mobilization, delaying it by a decisive two days. Thus Clark discredited the black legend of unilateral German aggression, and with it the popular thesis that democracies don’t start wars; democratic France, eager to regain the territory lost in its 1870 war with Prussia, encouraged Russia to mobilize. The somnambulant autocracies in Berlin and Vienna stumbled into the war.

The Sleepwalkers addressed the “how” of World War I’s beginning. In the diffuse, fascinating, and frustrating Time and Power, Clark addresses the “why” by way of a meditation on the shifting self-image of the German nation from the Thirty Years’ War to the Hitler period (i.e., 1618–1945). Having established that the statesmen of Europe walked in their sleep, Clark now wants to know what they were dreaming—the better to understand the great changes in politics currently underway.

Brilliant as an investigator, Clark is out of his depth as a philosopher of history. He worries that the liberal vision of history as progress will give way now to an atavistic nationalism that fabricates its past in order to repudiate history altogether. It may be too much to ask a historian of the Great War to take a benign view of nationalism. Clark certainly is justified in pointing to the risks attendant upon our present populist revival. As Angelo Codevilla observed recently in the Claremont Review of Books, “The Great War’s combatants…had become what one might call ‘idol states,’ objects of cult, ritual, and human sacrifice” (“Defending the Nation,” Winter 2018/19). I argued in my 2011 book How Civilizations Die that each of the European powers dreamed of its own national election as a new Chosen People. Nonetheless, Clark’s attempt to draw a parallel between the breakdown of the German state after World War I and the crackup of the 21st-century liberal order fails in both concept and narrative.

* * *

Clark has read his way into the theories of time which gained traction on the European continent during the 19th century. He cites Henri Bergson, Émile Durkheim, and Martin Heidegger, who “proposed that the ‘existential and ontological constitution of the totality of human consciousness [Dasein]’ was ‘grounded in temporality.’” Here we have an unintended irony: Clark draws on Heidegger to explain why a rupture in temporal sensibility risks encouraging a new kind of Nazism. But, he neglects to add, Heidegger’s own views on temporality led him to conclude that the concrete circumstances of his own time required support for Adolf Hitler. In 1933, during a conference at the University of Tübingen, the Marburg philosopher declared that

We have witnessed a revolution. The state has transformed itself. This revolution was not the advent of a power pre-existing in the bosom of the state or of a political party. The national-socialist revolution means rather the radical transformation of German existence.

That conference was organized by Tübingen’s local branch of the Nazi party. It is odd to warn that we risk a Nazi revival if we depart from a conceptual framework whose first conclusion was support for Nazism.

Clark reduces the issue of temporality to only two possible views: the linear notion of historical progress (à la liberalism) versus the perpetual present fed by obsession with an imagined past (à la premodern societies and Nazism). This juxtaposition leads Clark to the trivial (and wrong) conclusion that the populist rebellion against liberal progressivism represents a devolution to primitive, destructive expressions of nationalism.

Not only has the postwar liberal order failed, Clark avers; its intellectual foundation, namely the belief in progress over time, has fractured:

Liberal democracy is founded, no less than communism, on a linear understanding of history…. [B]oth systems are founded on the intention to change reality for the better; at the heart of both is an idea of modernization that requires “breaking from the old and initiating the new”…. Hence the strong attachment of recent Democratic presidents in the United States to the notion that there is a “right” and a “wrong” side of history. But…[t]he abysmal failure of liberal democratic “nation-building” projects in the wake of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars discredited the pretensions both of “democratic peace theory” and of the political culture that gave rise to it.

The horrible alternative to the fractured liberal order, Clark tells us in the book’s introduction, is Donald Trump, who “mounted a challenge…to conventional American historicity by becoming the first president of modern times overtly to reject the notion that America occupies an exceptional and paradigmatic place at the vanguard of history’s forwards movement.” As Clark sees it, “In the United States, Poland, Hungary, and other countries experiencing a populist revival, new pasts are being fabricated to displace old futures.”

In my view, the linear notion of historical progress which Clark takes for “conventional American historicity” is neither conventional nor American. It is not conventional, because the Progressive movement advanced it at the turn of the 20th century in radical opposition to American convention. And it is not American, but rather a Hegelian cuckoo’s egg deposited in America’s nest by the Baptist minister Walter Rauschenbusch and others in the Social Gospel movement. Later I will discuss the American notion of temporality. Let us first examine Clark’s narrative.

* * *

After claiming that trump and other populists resemble Nazis, Clark spends most of the book reviewing German history in order to arrive at a characterization of the Nazis that corresponds to his reading of Trump. He writes,

[German Chancellor Otto von] Bismarck’s historicity was riven by a tension between his commitment to the timeless permanence of the state and the churn and change of politics and public life. The collapse in 1918 of the system Bismarck created brought in its wake a crisis in historical awareness, since it destroyed a form of state power that had become the focal point and guarantor of historical thinking and awareness.

Among the inheritors of this crisis…were the National Socialists, who initiated a radical break with the very idea of history as a ceaseless “iteration of the new.”

Totalitarian regimes, Clark asserts, undertook “ambitious modern interventions in the temporal order.” They eschewed notions of progress in favor of a sentimental longing for their respective peoples’ mythic bygone days, so as to foster a sense of “deep identity between the present, a remote past, and a remote future.” The book devotes some attention to the Soviet Union’s official calendar, which in 1930 under Stalin was altered to replace the traditional seven-day week with a new one of five days, identified simply by colors and numbers. Clark calls this “a revolutionary experiment in reordering the human relationship with time.” But, oddly, he does not mention the great precedent for Stalin’s abortive experiment—namely the Jacobins’ ten-day week and renamed months. Perhaps this is because Clark likes the French Revolution, and blames the Nazis for having “neutralized” it.

* * *

Clark’s book compares the historical self-understanding of the Hohenzollern nobleman and Great Elector of Brandenburg Friedrich Wilhelm (ruled 1640-88), who built the state that would become modern Prussia and later modern Germany, to that of Bismarck in the 19th century and then that of the Nazi regime in the 20th. But this comparison is insufficient as an account of Germany’s national development. What was it that united the 36 major political subdivisions of Germany, guaranteed sovereignty in 1648 by the Peace of Westphalia, into one nation? It surely was not the Prussian monarchy. The Hohenzollerns, as Clark notes, had no historical connection to Brandenburg, the core of the future Prussian state, “purchased…in 1417 for four hundred thousand Hungarian gold guilders. Through strategic marital alliances, successive generations of Hohenzollern Electors had acquired territorial claims to a number of noncontiguous territories to the east and west.”

Under Friedrich Wilhelm’s grandson, Friedrich Wilhelm I, and great-grandson, Friedrich II (“the Great”), Prussia had neither the characteristics nor the self-understanding of a nation. Prussians constituted a minority of its soldiers during wartime, and German was a minority language in Berlin during most of the 18th century. Huguenots, Poles, Jews, and other immigrants replaced the majority of the population of Brandenburg and Pomerania that had been depleted during the Thirty Years’ War. Clark does not mention the man who compelled Prussia to transform itself from a territory, defined by the personal sovereignty of the monarch, into the core of the German nation. That man was Napoleon I. Napoleon’s levée en masse placed the whole of French manhood at his disposal and put a field marshal’s baton in the rucksack of every foot soldier, cutting through Prussia’s best armies and claiming swaths of its territory at the 1806 Battle of Jena. It was in the wake of this trauma that the atomized German princedoms began to develop a sense of national solidarity. The Hohenzollerns, then, were not the unifiers of the German nation.

* * *

Friedrich Wilhelm held power by right of personal sovereignty, rather than national sovereignty. In 1701 his son, Friedrich III, was crowned and anointed as Friedrich I, King of Prussia. Clark notes that the coronation ceremony was strangely lacking any sense of continuity with the past: “Publicists and councilors alike were quick to point out that the function of the anointment (Salbung) was purely symbolic. This was not a traditional sacrament, but merely an edifying spectacle designed to elevate the spirits of those present.” Clark thinks that Friedrich III’s vision of the state as “a historically nonspecific fact and a logical necessity” represents a break from the Great Elector’s view of history as an ongoing stream of change and forward movement.

He then attempts to show that Friedrich III’s vision of the timeless state began to clash with a more progressive model of history under Bismarck. But though he sketches Bismarck’s notion of historical time in a neatly drawn miniature, Clark misses the Teutonic forest for the trees. The Iron Chancellor wrote early in his career, “The stream of time runs its course as it should, and if I stick my hand into it, I do so because I believe it to be my duty, not because I hope thereby to change its direction.” And he added late in life, “Man can neither create nor direct the stream of time. He can only travel upon it and steer with more or less skill and experience.” From this we learn only that Bismarck was a pragmatist who sought to adapt the Prussian monarchy to changing circumstances and preserve the balance of power in Europe. Clark wants to get at the developing time-consciousness of German leaders before Hitler. But he has summoned a witness with nothing but banalities to offer.

It would have been instructive to compare the empty rigamarole of Friedrich I’s coronation with its British equivalent. The British monarchy, which claimed its thousandth anniversary in 1973, appropriates the Biblical ritual of anointment to emphasize the sacred character of the institution and its derivation from the Davidic monarchy. (This is portrayed touchingly in Episode 5 of the popular series The Crown, when George VI explains to his child Elizabeth that anointment is what makes one a monarch.) Britain appropriated elements of the biblical past into its own memory, with enormous success. The sense of sanctity attached to the sovereign has helped Britain muddle through for centuries with an unwritten constitution.

* * *

All the European nation-states but Germany arose out of such an act of cultural appropriation. Starting in the 6th and 7th centuries, when Saint Isidore of Seville and Saint Gregory of Tours urged the Visigoth and Merovingian kings to assume the mantle of the Davidic monarchy, the nations of Europe understood themselves as emulators of ancient Israel under the tutelage of the Church. Tribes and clans do not naturally agglomerate into nations; by itself, tribal society fractures into something like the 832 distinct languages (not dialects) presently spoken in New Guinea. Christianity transformed the tribes of Europe into nations by forming monarchies on the Biblical model and inculcating Biblical memory into its peoples.

No Western nation undertook this project more consciously and with greater deliberation than the present-day exemplar of a nation-state, the United States of America—the “almost chosen people,” to use a phrase from Abraham Lincoln’s 1861 address to the New Jersey State Senate. America’s national epic is the King James Bible. Its most characteristic work of literature, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, is derivative of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, as Harry V. Jaffa noted in a private conversation. Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address is our national sermon, and the Battle Hymn of the Republic with its paraphrase of Isaiah 63:1-4 is our national song.

The cultivation of German nationalism in response to the collapse of the 18th-century Prussian army at Jena took a different path. Clark’s failure to mention it is perplexing. He sticks to his contrast between liberal progressivism and Hitlerian nostalgia with academic stubbornness. This is unfortunate, because the understanding of time in Continental philosophy actually begins with the response of post-Kantian German philosophers to Napoleon’s triumph over the German monarchies. Immanuel Kant’s 1795 essay on “Perpetual Peace,” with its vision of an eternal and unchanging stasis among all nations, was both the epitome and swan-song of the Enlightenment. The revolt against the Enlightenment began with an attack on Kant’s theory of synthetic a priori reason, the faculty of a rational being that precedes and makes possible our comprehension of space, time, and morality. J.G. Fichte (1762–1814), later the philosopher of German nationalism, argued in his 1793 lectures at the University of Jena that Kant’s a priori synthetic reason had to be situated in human consciousness. His young student Novalis, perhaps the most influential of the German Romantics, insisted that all consciousness was temporally bound, anticipating Heidegger by more than a century, as Peter Charles Hanly of Boston College has shown in his 2014 essay, “Figuring the Between.”

* * *

Drawing on Augustine’s concept of time, Novalis understood the present as an “ecstatic” unity of memory and anticipation. His 1799 speech “Christianity or Europe” appealed to Europe’s medieval Christian past as a foundation for present European consciousness. The mythical Christian past would ennoble the legends of the profound past, and the disenchanted world of the Enlightened would be re-enchanted (Wiederverzaubert) in the legend-laced world of the Christian Middle Ages. Novalis’s program remained hugely influential for a century; one encounters it virtually unaltered more than a century later in T.S. Eliot’s careful references to James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough. J.R.R. Tolkien, who considered the English inheritance of Anglo-Saxon myth inadequate to provide a foundation for British culture, undertook to create his own array of pagan myths as a more congenial precursor to Christianity.

It is instructive to compare Novalis’s hope for the re-enchantment of Europe to America’s attitude toward its past. The unchanging past of European old-world society does not know time, but only “once upon a time.” Generations come and go, but life remains the same, and the past is identical to the future, blending into a perpetual present. But American time-consciousness leaves this old-world mentality behind and looks forward. This is neatly captured in one of our foundational stories, Washington Irving’s “Rip van Winkle.” Rip goes to sleep in the temporality of “once upon a time”—in Novalis’s enchanted world. He awakes after the American Revolution in a new temporality, in the clear light of the modern world.

* * *

But this American forward motion is not the utopian progressivism that Clark wants to identify with liberalism. Clark’s simple juxtaposition of progressive linear time and the changeless present of traditional society utterly fails to understand American temporality. America does not march toward the end of history, because its founders felt keenly Saint Augustine’s distinction between the heavenly city and the earthly city. The American journey does not proceed toward the earthly paradise of the progressives, but to a vanishing-point on the horizon. That is why the most impassioned religion can cohabit here with the rule of reason. The American eschaton is not imminent, but beyond the horizon. The American avatar of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim is Huckleberry Finn, who, in true American fashion, concludes his journey by starting a new one, lighting out to the new territory ahead of the others.

Sadly, Clark’s application of the Continental philosophy of time is reductionist and impoverished. That is his fault rather than that of the philosophers. Heidegger’s older contemporary, the great Jewish theologian Franz Rosenzweig, asserted in 1921 that the Biblical concept of time was the normative case. “Revelation is the first thing to set its mark firmly into the middle of time; only after Revelation do we have an immovable Before and Afterward,” he wrote in The Star of Redemption (1921). “Then there is a reckoning of time independent of the reckoner and the place of reckoning, valid for all the places of the world.” Rosenzweig never visited the United States or commented on its national character, but his intuition that the Biblical reckoning of time is “valid for all the places of the world” rings true by reference to America in one way and the United Kingdom in another. Biblical time is metaphysically different from the eternal present of primitive society: it begins with the irruption of the one Creator God into history, which sets a marker for past and future, as Rosenzweig observed.

* * *

In Heidegger’s construct, we absorb by mere repetition the heritage that fate has apportioned us. To be entschlossen, or decisive, means to Heidegger submitting ourselves to this fate. America by contrast adopted the heritage of Israel in an act of religious imagination. The Puritan “errand in the wilderness” with its vision of a new “city upon a hill” adopts the history of Israel as America’s spiritual history, the foundation for a new covenant. That is why America’s remembrance transcends the mere repetition of accumulated habits and experience and becomes instead what Lincoln called “[t]he mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone.” America looks back, not to a distant past of pagan legends, but to a Biblical history which it has chosen for the backdrop of its journey into a bright and glorious future.

In Germany, by contrast, the reconstruction of the past took a tragic direction that Novalis and the Christian Romantics failed to anticipate. Neo-pagans like Richard Wagner succeeded in mining the legendary past for a German identity founded upon race. This became the “national nervous fever” that Friedrich Nietzsche denounced in 1886 in Beyond Good and Evil: “the anti-French folly, the anti-Semitic folly, the anti-Polish folly, the Christian-romantic folly, the Wagnerian folly, the Teutonic folly, the Prussian folly…and whatever else these little obscurations of the German spirit and conscience may be called.”

The crux of Clark’s argument appears in his chapter on Hitler, which “builds a case for the distinctiveness of National Socialist temporality.” Hitler sought “to establish an ever more perfect identity with the remote past, out of whose still uncontaminated timbers the house of the future would have to be built. In the ‘longing for a common [German] fatherland,’ Hitler wrote, there lies ‘a well that never dries.’” Clark indulges in a lengthy peroration on the Nazis’ fascination with what he calls “the remote past,” including archeological investigation of Teutonic prehistory, cataloguing of folk customs, and other efforts to promote a culture of German racial identity. The reader well may ask whether the Nazis’ amateurish evocation of the mythic German past had anything like the impact of Wagner’s operas, especially the “Ring” tetralogy derived from 13th-century epic sagas in the Nibelungenlied and the Scandinavian Eddas. Not only did Wagner turn the remote German past into a dramatic parable for the present. He did so in a musical framework that subverted the forward-looking structure of musical time, which had prevailed from the composers of Renaissance counterpoint to the classical composers a generation before him. In 1852 Wagner wrote to the violinist Theodor Uhlig: “Time is absolute Nothing. Only that which makes time forgotten, that destroys it, is Something.”

* * *

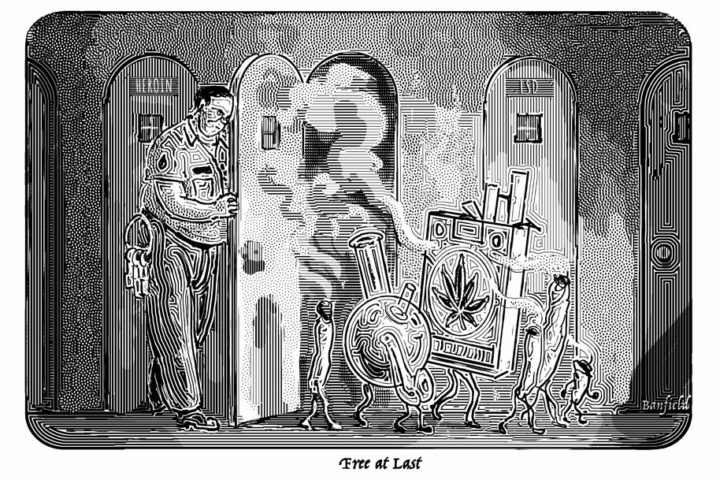

In Clark’s carnival-mirror comparison, Trump’s campaign rhetoric about restoring American greatness and reclaiming American manufacturing jobs evokes the same regression to a mythical past that beguiled the Nazis—as if the American steel industry, which in 1948 employed ten times more workers than it does today, were the equivalent of Nibelheim or Valhalla. That is a feverish instance of what Leo Strauss mocked as “reductio ad Hitlerum.”

To say that Trump has rough edges is an understatement, but it is nonsensical to identify “Make America Great Again” with the Nazi revival of the pagan past. America has no pagan past to revive. It was founded as a Christian nation with a Biblical culture, albeit low-church Protestant and antinomian. Trump was the overwhelming choice of evangelical Protestants in the primaries and won the highest proportion of the evangelical vote on record. Evangelicals supported Trump rather than one of their own, Texas Senator Ted Cruz, because they sought not a national pastor but the sort of rough man who would lead them in battle against the Philistines—a Jephthah or Saul rather than an Elijah. In a country whose founders held to the Calvinist doctrine of total depravity, rallying behind a sinner is not the least bit incongruous or un-Christian, much less Hitlerian.