Books Reviewed

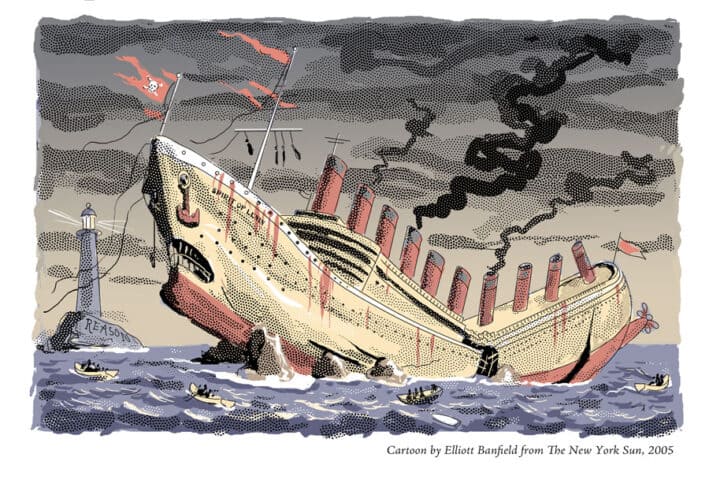

Since the dawn of the atomic age, when we gained the capacity to destroy everything there is, we have grown superficially accustomed to the possible end of civilized life—or even of all human life—on earth, blunting the edge of a wholesome and salutary fear. But, of course, to live with full, unremitting awareness of how precarious our condition really is would be intolerable, so a certain insouciance proves wholesome, and salutary, too. The balance of terror—a term commonly used in the current unnerving geopolitical situation—pertains as well to the individual psyche, which must somehow achieve an equilibrium between cringing abjection in the face of the all-too-real possibility of thermonuclear holocaust and cavalier indifference to a cataclysmic war one may be sure will never happen—pretty sure, anyway, and not any time soon.

This modern predicament furnishes the backdrop for The End of Everything: How Wars Descend into Annihilation by the masterly Victor Davis Hanson, which concentrates on four wars long ago. Although only seven pages in the final chapter are devoted to contemporary flash points where wars of annihilation could be touched off, one feels the presence of these current dangers throughout the book. One wonders whether Hanson, a senior fellow in military history at the Hoover Institution and author of over two dozen titles, would have written it if the perils were not so abundant and so incendiary: Russia and Ukraine, China and Taiwan, North Korea and South Korea (and Japan), Iran and Israel, Pakistan and India, Turkey and Greece (and Armenia and the insurgent Kurds to boot). It hardly needs saying that the United States and its democratic allies would be implicated in pretty nearly all such explosive conflicts-to-the-death. While he offers no policy prescriptions for dealing with the relevant evildoers and madmen, Hanson is clearly alert to the frightful ease with which worst comes to worst, and he demonstrates the need for the indispensable political virtue of circumspection in the age of nuclear weapons. (He clearly relishes, however, President Trump’s response in 2018 when Kim Jong Un boasted of the nuclear button on his desk: the American commander-in-chief has a bigger button, and his works—even if the gibe didn’t do much to slow North Korea’s arms program.)

***

The four civilizations on which Hanson focuses are the Greek city-state of Thebes, which Alexander the Great of Macedon obliterated in a one-day war in 335 B.C.; the Punic empire, reduced to the imperial city of Carthage, which a vengeful Rome razed in the Third Punic War in 146 B.C., after a three-year siege; Constantinople, the Greek Byzantine nonpareil, stronghold of Christendom in the East for over a thousand years, which fell to the Ottoman army of Sultan Mehmet II, henceforth known as the Conqueror, in 1453; and the Aztec Empire, with its magnificent island capital of Tenochtitlán, which Hernán Cortés and his force of Spanish conquistadors and native Tlaxcalan warriors extinguished in 1521. Hanson leaves no doubt about what is meant by a people said to have been “ended.” Merely to be conquered, occupied by the enemy, and made permanently subservient is not enough to qualify for this distinction. Nothing short of total ruin will do: the end of everything comes “when a state’s government disappears, its infrastructure is leveled, most of its people killed, enslaved, or scattered, its culture fragmented and soon forgotten, and its space abandoned or given over to another and quite different people.”

The chapter on the Theban extinction takes its title, “Hope, Danger’s Comforter,” from that classic text of Realpolitik, the Melian Dialogue in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War. When the Melians, a small island colony of Sparta, resist the Athenian suggestion to surrender to overwhelming force, the Athenian spokesman reminds the plucky upstarts that hope tends to be extravagant and deceptive, and that those who stake their lives on it “see it in its true colors only when they are ruined.” Just as the Athenians left Melos utterly desolate, to be repopulated with Athens’ own colonists, so Alexander disposed of the too hopeful Thebans. Excited by rumors that Alexander had been assassinated and confident that the Macedonians could now be crushed, the Thebans prepared to lead a Panhellenic rebellion against the foreign invader but could convince no other city to follow. Their pride in their own storied military excellence precluded a sober assessment of their now-diminished power, and their belief in their moral superiority as the agent of destiny, bearing democracy and freedom to subjugated Greek city-states, plunged them into a conflict they couldn’t possibly win.

Fellow Greeks simply did not see the Thebans as Thebans saw themselves. An episode of shameful treachery a century and a half before, when the Thebans had abandoned the Greeks in order to ally themselves with the invading Persians (and had lost), still inflamed patriotic Greek hearts. Alexander exploited this Theban lapse into baseness in his propaganda: what self-respecting city would entrust its fate to so churlish an ally?

Alexander left the city’s destruction principally to other Greeks under his command. The peoples who knew the Thebans best hated them the most. Thebes’ Boeotian neighbors—poor country cousins to the arrogant metropolitan swells—were especially eager to plunder, rape, and murder. “The Theban-haters would get their chance at revenge and profit. The Macedonian-haters could blame fellow Greeks rather than Alexander for the slaughter,” observes Hanson.

Self-interest was probably paramount among Alexander’s reasons for laying waste to Thebes. A reputation for mercilessness would serve his purpose admirably as he rampaged onward in pursuit of his project to conquer the known world. But vengeance in the name of honor also moved him to savagery. The Thebans’ swaggering defiance of his quite reasonable peace overtures and other poisonous insults to the thin-skinned young king made him call for blood.

Five centuries later, Arrian, the hero-worshipping chronicler of Alexander’s campaigns, would call the ruin of Thebes the greatest loss the Greeks had ever suffered. As Hanson writes, this “complete destruction had a catastrophic political and psychological effect on the Greeks for decades to come.” It effectively ended the epoch of prospering independent city-states.

***

Unlike the refractory Thebans, the Carthaginians in 149 B.C. were agreeable and conciliatory when first faced with an immense besieging army—the Roman legions—in “perhaps the largest amphibious force seen in the ancient world since the 480 B.C. invasion of Greece by Xerxes.” The pretext for the invasion was Carthage’s violation of a treaty that forbade its fighting with anyone without Roman permission: it had defended itself against Numidian attacks, and Roman arms, the Romans declared, were only there now to uphold the peace. Cowed by the strength of the invading force, the Carthaginians acceded to the severe demands of the Roman “negotiators,” who insisted on 300 hostages during the talks, an end to the capture of elephants and their use in battle (which Hannibal had employed to great effect in taking the fight to Rome during the Second Punic War of 218-202 B.C.), destruction of most of their ships, and surrender of all their arms and armor. After Carthage had made these concessions, the Romans added an impossible demand: “a surreal order requiring nearly half a million Carthaginians to vacate and destroy their ancient harbor city of seven hundred years.” Roman magnanimity would permit the Carthaginians to rebuild anywhere they liked, provided it was at least ten miles from the sea.

It became clear to everyone that Rome had sought war all along, and now Carthage had virtually disarmed itself as it faced the deadly onslaught. The city’s outraged populace frog-marched, stoned, and further abused the ambassadors who had been so supinely compliant. But Carthage wasn’t finished: industry fervent with desperation produced weapons at an astounding rate, and soon almost replaced the arms they had surrendered. The city was readying itself for “an existential war against Rome, the clear aggressor.”

***

Carthage was the most formidably fortified city in the ancient world, with walls 40 feet high and 30 feet thick, but at this point it was “a great imperial city without an empire.” Given the inequality between the rival cities, there seemed to be no need for the devastating Roman viciousness. But Rome had its reasons. Payment must be exacted for the century of trouble that Carthage had caused: never forgotten were the Second Punic War’s 300,000 Roman dead and Hannibal’s rampage down the Italian peninsula, brought up short distressingly near the heart of the empire. In the Roman mind, Carthage seemed to pose an ever-present danger, however peaceable it had been since its defeat in 202 B.C. One did not have to be a hardliner to be horrified by the Carthaginian practice of child sacrifice and to fear the worst from such monsters. Roman parents correcting difficult children would frighten them with the warning “Hannibal at the gates!” The tykes could readily suspect what the old bogeyman had in store for them. The very old Cato the Elder, who remembered Hannibal well, famously closed his speeches in the Senate with his war cry “Carthago delenda est!” (Carthage must be destroyed).

And destroyed it would be. Once the walls were breached, it took six days of plentiful carnage to end the resistance. Carthaginian dead piling up in the narrow streets got in the way as Romans proceeded to kill more and more, as many as they could. Perhaps 50,000 (of the 100,000 left in the city at the Roman breakthrough) were allowed to survive the butchery, and were sold into slavery. “Once the ravaging was complete,” Hanson records, the Romans “demolished the huge ancient walls, toppled all the remaining buildings, and torched anything combustible—bringing to an end some seven hundred years of Punic civilization in Africa.” Here was the origin of the choice phrase “Carthaginian peace.” Legend has it that the ground where the city had stood was sown with salt. “The destruction of Carthage did mark the end of one age, and the beginning of a new epoch when Rome would no longer feel itself threatened by any rival Mediterranean power that might bring war home to Italy itself.” Carthage was neither the first city nor the last to be razed by the Romans; they made total war quite normal, even known as “the Roman custom.”

***

Unlike the Thebans and the Carthaginians, the denizens of Constantinople had a clear idea from the start just what sort of enemy they were dealing with. The barbaric cruelty of the Turks, especially in the wake of victory, made them the most terrifying foe in Europe or Asia; one might call their brutality “the Ottoman custom.” So, the Byzantine Christians rightly feared the Islamic hordes who had long eyed their city, that pearl of great price, the Rome of the East, bastion of Church and empire, which “had lasted some 977 years after the capture of Rome and the demise of its Western empire,” and which had also inherited “the brilliance and achievements of classical Greece.” Despite their uneasiness in the face of Muslim envy and ambition, the Byzantines were confident in their hitherto impregnable seaside and land defenses—too confident, fatally—and firm in the belief that God was on their side. Not a few held that divine intervention would save them from the unspeakable depredations of the infidel, and Hanson quotes from Edward Gibbon’s monumental history at length: “an angel would descend from heaven, with a sword in his hand, and would deliver the empire, with that celestial weapon, to a poor man seated at the foot of [Constantine’s] column.”

Yet even though the angel failed to descend, Constantinople manfully held off the sultan’s siege for two months. Thanks in large part to the conspicuously gallant leadership of Genoese mercenary captain Giovanni Giustiniani, the Turks seemed to be beaten, and it was rumored that Mehmet II was preparing to lift the siege and withdraw his troops from the scene. But at the fateful moment it was the indispensable man who fell mortally wounded. Giustiniani’s Genoese followers started a panic that spread swiftly throughout the defenses. The most imposing fortifications in the world, the Theodosian Walls, were breached for the first time in history, on the city’s death day: May 29, 1453.

***

Like Carthage, Constantinople was a shrunken remnant of its former imperial glory, its population down to some 50,000 from its earlier 500,000, the bubonic plague having worked its will there, and multitudes having fled for fear of the Turk. Hanson writes that Constantinople on the downslope of its history was “not properly an empire at all, but a commercial city-state,” hardly worth an invader’s trouble in subduing it, if not for the magnificence of its setting and architecture. Feeble as it had become, it might still have been saved. To their lasting shame, the Byzantine Greeks of the Peloponnesus and the Aegean islands failed to come to the aid of their “mother city.” The Hungarian, Georgian, and Black Sea Christians also ducked the fight; the Roman Catholics of Western Europe, preoccupied with the Hundred Years’ War and fearful of the Ottomans, kept their distance as well. The nearly triumphant valor of the 700 Genoese mercenaries, with Giustiniani the appointed commander of the entire city’s land defenses, suggests that a small additional Western force could have turned the tide.

The victorious Turks poured into the city and lived up to their reputation for freebooting avarice if not that for limitless bloodthirstiness. Mehmet the Conqueror told his troops that he coveted “only the city, the walls, and its buildings. For three days, everything else in Constantinople—money, people, property—was theirs to do with and profit from as they pleased.” Any restraint his men showed was purely self-serving: slaves to be put to use or sold were more profitable than corpses, so only about 5,000 residents were slaughtered, all the rest consigned to bondage.

Mehmet himself envisioned the transformation of Constantinople’s remaining shell into the most resplendent Muslim city there was, and his vision was in fact realized. Constantinople’s crown jewel, Hagia Sophia, the grandest cathedral in Christendom, was refitted with minarets and became Istanbul’s crown jewel, the most recognizable mosque in the Islamic world. “May 29, 1453, also marked a great historical divide in which the ideas of ‘Asia’ and ‘Europe’ would permanently be delineated by Turkish Istanbul,” notes Hanson, “on the premise that the Western city of Constantine was actually always on Asian soil and thus culturally and politically had returned to where it belonged…. In the Ottoman creed, Asia was to be for Asians—and eventually Europe as well.”

***

In the Spanish imperial creed, the New World was for those conquistadors strong and daring enough to seize whatever they wanted, no matter to whom it might originally have belonged. For the glory of God and the glitter of gold, Hernán Cortés and his intrepid band bore the cross and the sword into the heart of the Aztec Empire, perhaps the wealthiest and certainly the most inhuman culture the men of the Old World would ever encounter. “The result was unending slaughter, a carnage that not only climaxed the defeat of the Aztecs but also ensured the eventual extinction of their civilization.”

It was not the relatively small force of the Spaniards, however, who pressed the massacre to the point of extermination: it was their Indian allies, warriors in the tens of thousands from Tlaxcala, like all the Aztecs’ neighbors perennially at war with the tireless predators of that supreme Mexican civilization, and better able than the rest of those neighbors to hold their own in battle and preserve their autonomy. The Tlaxcalans had the best of reasons to hate and to want revenge on the Mexica, as the Aztecs called themselves: this most savage of civilizations went to war principally in order to collect participants for their ritual human sacrifices, in which the priest, standing atop a pyramid 90 feet high, would carve open the living victim’s chest with an obsidian knife and rip out his hot beating heart. The organ would serve as an offering to the war god, Huitzilopochtli, and sometimes the priests would eat it on the spot, while the more profane remains were thrown to the ground below to be a feast for cannibals or hungry dogs. The numbers of the sacrificed are staggering—some 20,000 at several altars during a four-day ceremony to dedicate the reconstruction of the foremost Aztec temple.

And the horror-show experience of the Spaniards who witnessed their own comrades taken in battle and subjected to those ungodly rites both terrified them and roused them to pitiless ferocity. The conquistadors lost badly long before they won. During the Noche Triste, the Night of Sorrow, half of the men in the Spanish force of 1,500 were cut down as they tried to flee the capital city, or were commended to the gods Mexica-style. The huge Aztec army pursued the departing remnant for a week but, inexplicably, never swooped in for the kill—a “fatal mistake,” Hanson rightly concludes. For little more than a year later, Cortés and a mere thousand Spanish soldiers returned to Tenochtitlán with an enormous Tlaxcalan contingent and dealt the Mexica empire its death blow. Hanson makes the interesting suggestion that, while the Tlaxcalans’ principal motive in wiping out the Aztecs was justified revulsion at their unclean religion (which made Tlaxcalans its habitual victims), the Spaniards had other reasons just as convincing: “ending human sacrifice and cannibalism later became Spanish…justifications for the destruction of the Aztec Empire, as if the acquisition of gold, labor, and land were secondary considerations.”

***

Awful deeds are done for what Machiavelli called “the natural and ordinary desire to acquire.” And winning power and renown figures just as largely in most imperial ambition as acquiring vast riches. The annihilators of civilizations were empires on the rise, while the civilizations annihilated were one-time powers on the way down and out. Total destruction is rare in war, Hanson recognizes, because a people in danger of losing everything can see devastation coming and can choose to live on their knees rather than die on their feet, as he puts it. A survivable calamity is usually preferable to annihilating cataclysm. For a number of reasons—hope that help from allies will arrive, unjustified self-assurance that one’s own military prowess and unbreakable defenses can fend off any attacker, confidence that the enemy is more decent than he really is—certain civilizations did not see that the very worst was more than possible and in their blindness were torn out by the roots.

Victor Davis Hanson, impressively learned, imaginative, temperate, and discerning, has written a history of the most vicious old wars that is also instructive in dealing with modern monsters. Unfortunately, the people who need that instruction most are the least likely to take it.