Books Reviewed

When Chief Justice William Rehnquist was diagnosed with anaplastic thyroid cancer late last October, speculation began to rage concerning who will succeed him upon his retirement. Justice Antonin Scalia has figured prominently in those speculations. He is mentioned as President Bush’s likely nominee—if so, he would be the fourth Associate Justice in U.S. history to be elevated to Chief Justice—and the press has reported that Scalia is “running” for the job. Even if Bush fails to nominate Scalia, the thinking goes, he will certainly nominate someone like him. From the earliest days of the 2000 presidential campaign, after all, Bush declared his intention to appoint justices of Scalia’s sort. Which invites the question: And what sort would that be?

In the words of Professor Jerry Goldman at Northwestern University, “On a bench lined with solemn gray figures who often sit as silently as pigeons on a railing, Scalia stands out like a talking parrot.” Scalia’s opinions—whether Opinions of the Court, concurrences, or dissents—are more often included in the leading constitutional law casebooks, in both the law school and political science markets, than those of any other sitting justice. And his wonderfully crafted, often devastatingly witty opinions have also made him the subject of more academic inquiry and debate than any of his colleagues. According to Lexis-Nexis, Scalia’s name appears in 45% of all law review articles that mention in their title a current Supreme Court justice.

During his 20 years on the High Bench, the gregarious, poker-playing, opera-loving, former University of Chicago law professor has emerged as the Court’s most outspoken, high-profile, and personally colorful member. He relishes the cut and thrust of debate, and has institutionalized the practice of hiring, and then carefully listening to, a “counter-clerk” with liberal views at odds with his own and those of his other three clerks. With a distinctive style of questioning that is by turns testy, confrontational, and provocative, he asks questions during oral argument that are demanding yet laced with impish humor. On one occasion, he told a flustered attorney frantically searching his brief for information, “Just shout ‘Bingo’ when you find it.” His opinions are carefully wrought, powerfully argued, and filled with well-turned phrases. Two examples may suffice here: “[N]o government official is ‘tempted’ to place restraints upon his own freedom of action, which is why Lord Acton did not say ‘Power tends to purify.'” And asking states that bar the death penalty about its constitutionality is “rather like including old-order Amishmen in a consumer-preference poll on the electric car. Of course they don’t like it, but that sheds no light whatever on the point at issue.”

Two new books—Kevin A. Ring’s Scalia Dissents and Paul I. Weizer’s The Opinions of Justice Antonin Scalia—present Scalia’s opinions to the general public. Each contains brief but intelligent introductory essays on Scalia’s textualist approach to constitutional interpretation, followed by well-chosen samples of Scalia’s clear, accessible opinions on a variety of topics—especially in the area of civil rights and liberties.

Both Ring and Weizer provide thoughtful overviews of Scalia’s jurisprudence. Scalia argues that primacy must be accorded to the text, structure, and history of the document being interpreted and that the judge’s job is to apply the Constitution’s language or the structural principle necessarily implicit in the text. If the text is ambiguous, yielding several conflicting interpretations, Scalia turns to the specific legal tradition flowing from that text—to “what it meant to the society that adopted it” (this stance has opened him to charges of legal positivism and unqualified majoritarianism).

* * *

“Text and tradition” is a phrase that fills Justice Scalia’s opinions. Judges are to be governed only by the “text and tradition of the Constitution,” not by their “intellectual, moral, and personal perceptions.” In his words, “[W]hen judges test their individual notions of ‘fairness’ against an American tradition that is deep and broad and continuing, it is not the tradition that is on trial, but the judges.” Thus for Scalia, reliance on text and tradition is a means of constraining judicial discretion. He believes that “the main danger in judicial interpretation of the Constitution—or, for that matter, in judicial interpretation of any law—is that the judges will mistake their own predilections for the law.”

Scalia holds that the Constitution creates two conflicting systems of rights. One is democratic—the right of the majority to rule individuals; the other is anti-democratic—the right of individuals to have certain interests protected from majority rule. He relies on the Constitution’s text to define the respective spheres of majority and minority freedom; and when that fails to provide definitive guidance, he turns to tradition to tell the Court when the majoritarian process is to be overruled in favor of individual rights. He thinks that by identifying those areas of life traditionally protected from majority rule, the Court can objectively determine which individual freedoms the Constitution protects. “I would separate the permissible from the impermissible on the basis of our Nation’s traditions, which is what I believe sound constitutional adjudication requires.”

Scalia therefore would overrule the majority only when it has infringed upon an individual right explicitly protected by the Constitution’s text or by specific legal traditions emanating from it. In his 1996 dissent in United States v. Virginia, in which the Court proclaimed that the exclusively male admission policy of the Virginia Military Institute violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, he declared that the function of the Court is to “preserve our society’s values, not to revise them; to prevent backsliding from the degree of restriction the Constitution imposed upon democratic government, not to prescribe, on our own authority, progressively higher degrees.” As he powerfully argued in his 1990 dissent in Rutan v. Republican Party, in which the Court held that political patronage violates the free-speech rights of public employees:

The provisions of the Bill of Rights were designed to restrain transient majorities from impairing long-recognized personal liberties. They did not create by implication novel individual rights overturning accepted political norms. Thus, when a practice not expressly prohibited by the text of the Bill of Rights bears the endorsement of a long tradition of open, widespread, and unchallenged use that dates back to the beginning of the Republic, we have no proper basis for striking it down. Such a venerable and accepted tradition is not to be laid on the examining table and scrutinized for its conformity to some abstract principle of First Amendment adjudication devised by this Court…. When it appears that the latest “rule,” or “three-part test,” or “balancing test” devised by the Court has placed us on a collision course with such a landmark practice, it is the former that must be recalculated by us, and not the latter that must be abandoned by our citizens.

Following their introductory essays, Ring and Weizer provide a rich array of Scalia’s opinions in which his textualism is on full display. Ring, an attorney in private practice in the Washington, D.C., area and former counsel to the Subcommittee on the Constitution of the U.S. Senate’s Judiciary Committee, focuses on Scalia in dissent. Although he admits that the title of his book is not “technically accurate” because he includes several of Scalia’s concurrences as well, he defends Scalia Dissents as “fitting because nearly every opinion reveals Scalia in strong disagreement with the reasoning, if not the conclusion, of a majority of the Court.” He provides 19 unedited dissenting and concurring opinions chosen “not necessarily” because they are “Scalia’s most important” but because they “are the most interesting to read.” Some are, in fact, among Scalia’s most important, including his dissent in Morrison v. Olson (in which the Court upheld the constitutionality of the independent counsel statute against Scalia’s powerful separation-of-powers argument—the only case in either volume in which Scalia addresses the text of the original Constitution itself as opposed to the Bill of Rights or the 14th Amendment). Ring also includes Scalia’s valuable dissents in Lee v. Weisman (in which the Court held that a nondenominational prayer at a public school graduation violated the Establishment Clause), McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (the case upholding the McCain Feingold campaign finance reform), Planned Parenthood v. Casey (the Court affirmed the constitutional right to abortion first announced in Roe v. Wade), and Lawrence v. Texas (in which the Court invalidated a Texas statute criminalizing homosexual sodomy).

Others are less important but just plain fun to read. For instance, Ring includes Scalia’s dissent in PGA v. Martin, in which his colleagues concluded that the provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) required that Casey Martin, a professional golfer suffering from a degenerative circulatory condition, be allowed, in violation of PGA rules, to use a motorized cart during tournaments. Scalia obviously enjoyed himself as he mocked the Court’s work:

It has been rendered the solemn duty of the Supreme Court of the United States…to decide What Is Golf. I am sure that the Framers of the Constitution, aware of the 1457 edict of King James II of Scotland prohibiting golf because it interfered with the practice of archery, fully expected that sooner or later the paths of golf and government, the law and the links, would once again cross, and that the judges of this august Court would some day have to wrestle with that age-old jurisprudential question, for which their years of study in the law have so well prepared them: Is someone riding around a golf course from shot to shot really a golfer? The answer, we learn, is yes. The Court ultimately concludes, and it will henceforth be the Law of the Land, that walking is not a “fundamental” aspect of golf.

Scalia had his doubts. He noted that “many, indeed, consider walking to be the central feature of the game of golf—hence Mark Twain’s classic criticism of the sport: ‘a good walk spoiled.'”

* * *

Weizer’s selection of opinions is different from Ring’s in two important respects. Weizer, an Associate Professor of Political Science at Fitchburg State College in Massachusetts, limits himself expressly to Scalia’s opinions on civil rights and liberties, but he also includes several opinions in which Scalia wrote for the Court majority, including a Free Exercise case (Employment Division, Oregon Department of Human Resources v. Smith) and a Free Speech case (R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul). Weizer edits Scalia’s opinions more heavily than Ring and thus is able to include 25 opinions in a shorter book. His selection overlaps substantially with Ring’s (11 of the same opinions appear in both books); however, his interest in criminal procedure is apparent. He includes four important Scalia concurrences and dissents concerning the rights of the accused and four more on the meaning of “cruel and unusual punishments.”

Since his appointment to the Supreme Court, Scalia has written over 600 opinions. Given so many from which to choose, Ring’s and Weizer’s selections are entirely defensible and, indeed, admirable. Still it is worth noting that by limiting himself to Scalia’s dissents and concurrences, Ring has deprived his readers of Scalia’s important opinions for the Court on judicial power, standing, federal pre-emption, and the Takings Clause, as well as Scalia’s problematic opinions in the field of state sovereign immunity (e.g., his opinion in Blatchford v. Native Village of Noatak in which he expressed the decidedly anti-textualist view that the 11th Amendment “stand[s] not so much for what it says, but for the presupposition…which it confirms”). Likewise, by including only Scalia’s opinions on civil rights and liberties, Weizer has deprived his readers of Scalia’s classic concurring or dissenting opinions on separation of powers, the “negative” Commerce Clause, and the war on terror, not to mention Scalia’s questionable dissents strictly limiting Congress’s enforcement powers under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment (Nevada Department of Human Resources v. Hibbs and Tennessee v. Lane).

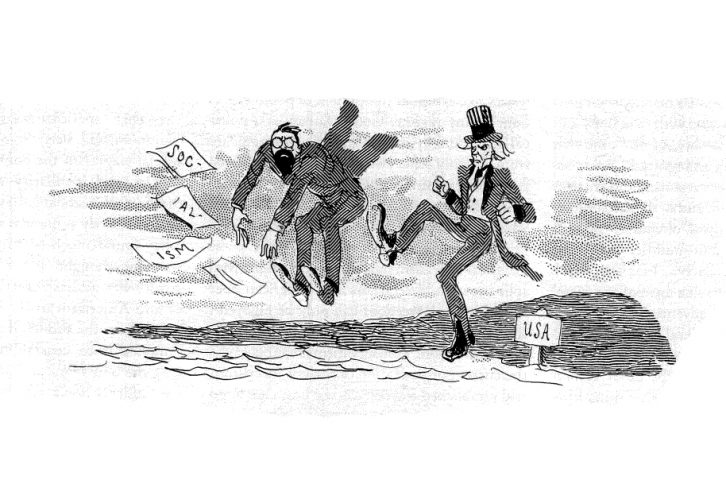

Such criticisms, however, are minor. These are two excellent introductions for the general public to the judicial philosophy of one of the Court’s most talented—and certainly most vocal—jurists. Ring and Weizer concur in describing a justice who has remained faithful to the “text and tradition” of our written Constitution; who has steadfastly rejected the idea of a “Living Constitution” and other novel theories of interpretation that have the invariable effect of transferring power from the popular branches to the judges; and who has sought to constrain judicial discretion and, with all the considerable intellectual tools at his disposal, has fought the tendency of judges to substitute their beliefs for society’s. In so doing, he has reminded his colleagues and the public at large of the most important right of the people in a democracy—the right to govern themselves as they see fit and not to be overruled in their governance unless the clear text or traditional understanding of their Constitution demands it.